In the 1920s and 1930s, there was a cultural and artistic explosion in North Omaha. Influence came to the city from New York, where the Harlem Renaissance was born. However, North Omaha actually influenced Harlem and the movement that wrapped across the United States and beyond. This is a history of the Harlem Renaissance in North Omaha.

Omaha Needed This

Its rudimentary to say that Black people have always been advanced in creative, inventive, intellectual and artistic ways. However, in many ways African Americans have been far more advanced than European Americans. Long before the enslavement of Africans began, European Americans and their European ancestors routinely took African innovations back to white people and claimed these creations as their own. Enslavement in America didn’t stop the innovations of Black people, but thwarted them a lot.

In the decades after the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, Black people across the United States flourished in many ways. People of African descent had been in Nebraska long before its statehood. Eventually many became successful farmers, entrepreneurs, social leaders and political activists. However, the force of white supremacy was at work oppressing these early pathfinders and fighters through terrorism and systemic racism, and it often worked through both in loud, explicit attacks on Black people and through systemic racism that was baked into the culture of the state. Despite a consistent presence, determined leadership and increasingly significant contributions throughout Omaha, for more than 60 years after the Civil War the voices of Black people were often squelched and denied, persecuted and ignored throughout the city.

In 1910, Omaha had 4,426 Black residents, forming 3.6% of the city’s population of 124,096 people. In what is referred to as the Great Migration, during the next ten years Omaha’s Black population doubled in size. All elements of the city’s Black community grew exponentially, including the economic, religious, cultural, political and social sectors. Creative people, leaders and motivators built things, created Art, and got things done like never before.

Along North 24th Street from Cuming Street to Lake Street Black-owned businesses and enterprises mixed with Jewish-owned and white-owned businesses, and while no conditions were perfect, the area thrived.

There was a successful scene for Black artists in Omaha in the 1910s. It was 1916 when the first-ever Black-owned film company opened in North Omaha. Called the Lincoln Motion Picture Company, it stayed in town for just a year, but continued from Los Angeles for five years, producing many important films and influencing generations afterwards. Along with earlier popular performers including Dan Desdunes (1870-1929), Maceo Pinkard (1897-1962) started his career in Omaha in 1917 running a theatrical agency. His song “Sweet Georgia Brown” was a Billboard #1 hit in 1925. Coming into the Harlem Renaissance, traveling Jazz bands and local ragtime bands had a firm hold and were ready for new relevance.

One of the emergent families in North Omaha were the Broomfields. Led by crime boss Jack Broomfield, his brother Levi was a popular singer nationally and his adopted son LeRoy (1902-1971) became an international performer noted for his musicals, dancing, singing and teaching.

It was against this backdrop that the force of transformation, which was then called the “New Negro Movement,” arrived. This period is now referred to as the Harlem Renaissance,” and according to Wikipedia it “was an intellectual and cultural revival of African-American music, dance, art, fashion, literature, theater, politics and scholarship.” Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Black culture moved to the front of the American popular consciousness, focused by Black power and protest. In 1925, a Black newspaper called The New York World observed there were “a number of… intellectual, social and financial leaders to guide… the response to the new environment is already striking, and promises to affect the Negro all over the United States.” The Harlem Renaissance came to Omaha.

The Harlem Renaissance Arrived in Omaha

After the horrors of World War I and the 1919 lynching of Will Brown though, a combination of determination, rebellion and excitement swept through the African American population in Omaha. While present throughout the history of Nebraska, within a year after the Red Summer, Black culture, art, literature, and music began ringing out loudly and proudly in cities with big African American populations, and Omaha was one of those cities.

Between 1920 and 1930, Omaha’s Black population doubled with migrants from the South coming for jobs, perceived freedom from Jim Crow, and culture. By 1920, there were 10,315 Black residents in Omaha comprising 5.4% of the city’s 191,601 residents.

The major population center was in North Omaha along North 24th Street from Cuming to Lake Streets. Referred to as the Near North Side, starting in the 1860s, that term originally applied to a specific neighborhood where Black people lived around North 8th and Dodge Streets. By the 1920s, it came to mean wherever Black people lived north of Dodge Street, including surrounding North 24th Street. At the same time there were smaller Black neighborhoods in South Omaha.

My research shows that at this point, the nexus of white flight and Black empowerment led to the emergence of Black culture as a predominant force within the Black community and as a majorly influential force throughout the rest of Omaha.

In the 1910s, the Near North Side developed a thriving jazz scene and welcomed a growing community of Black artists, writers, and intellectuals. Black-owned businesses emerged in the aftermath of the 1913 Easter Sunday tornado that obliterated hundreds of homes in the neighborhood. Before 1920, businesses owned by African Americans in North Omaha included law offices, healthcare offices, hotels and boarding houses, haircare, groceries, funeral homes, pharmacies, real estate agents, private schools, various stores and a tailor. There were also speakeasies, and after Prohibition ended, bars and nightclubs throughout the Black community.

Working in meatpacking plants in South Omaha, for the railroads and in private homes throughout North Omaha, Omaha’s African American working class was the largest sector of the community. Thousands of people lost their jobs in 1929 when the Great Depression set in. That didn’t stop the community from responding though, and there were new attitudes and abilities that grew during the 1930s. For instance, Omaha’s Emancipation Day celebrations of the 1920s were well-attended and noted for their jubilance; however, they didn’t climax until the late 1930s when thousands turned up at the old Omaha Civic Auditorium for grand celebrations.

Significant cultural events noted in local newspapers from the era included funerals. The funeral of Jack Broomfield (1865–1927), a notorious Black crime leader in Omaha, was one. When he died, the roster of pall bearers was a who’s-who from the community, with white and Black men included equally, as well as policemen and known criminals. The 1931 funeral of community leader Andrew M. Harrold (1859-1931) reflected the increasing grandiosity of the community. “Lasting hours,” the event including a sermon from the Zion Baptist Church minister, as well as rites from the Prince Hall Masons, the Knights and Daughters of Tabor, and the United Brothers of Friendship. It was written about the in the Omaha World-Herald as well as The Guide, as well.

Newspapers and radio stations were the dominant media in Omaha during this time. While a half-dozen newspapers were started by Black people in Omaha before 1920, the most important was The Monitor, a popular African American newspaper run by a progressive Black minister. It was pro-Black, championing the New Negro Movement, Black uplift, and Black cultural superiority. Along with a few other Black-owned newspapers that came and went, this papers played the crucial role of igniting and sustaining the Harlem Renaissance in Omaha. It also encouraged the Great Migration that brought a lot of African Americans from the rural South to Omaha, literally doubling its Black population during the 1920s.

Along with the newspapers, one of the main way Omahans learned about the Harlem Renaissance was through movie theaters in the neighborhood that showed Black movies and news. The Franklin Theatre was opened at 1624 North 24th Street in 1909 and stayed open until 1926. In 1911, the Alhambra Theater was opened at 1814 North 24th Street, closing in 1931. One of the most popular Black theaters in North Omaha was at 2410 Lake Street and was called The Lake Theatre, which opened in 1913. It closed permanently by 1958. The Lothrop Theatre was opened at 3212 North 24th Street in 1914 and ran until 1955. The most popular Black theater in North Omaha was the Ritz Theater, opened in 1931 at 2043 North 24th Street and not closing until the early 1960s. During the 1920s and 1930s, these were the main theaters open to Black customers in the neighborhood. There were also two large theaters in downtown Omaha that had segregated seating for Black customers in the balconies.

That’s how Black writers, artists, musicians and other creators emerged in Omaha during the 1920s to leave a literary and cultural legacy, and inspiring the future to emerge faster.

Surrounding Omaha’s Harlem Renaissance

This article explores some of the ways that these Black Omahans contributed to the city, to America and to the world during the Harlem Renaissance. They stood up, spoke out and created art, music, literature or other innovations that made the world a better place.

My ongoing of historical examination of Omaha’s African American population has shown that upperclass residents began standing up their presence during the 1910s. By the early 1920s, they had a firm, identifiable cultural presence that was supported by the religious and professional sectors. The professional class was formed by doctors, lawyers, educators, and successful business owners.

This upperclass was an operational patriarchy exclusively for men, but there were specific roles for women throughout the social clubs and other functions of the elite class. Often operating as “auxiliary” units to men’s organizations, women were organizers, operators and leaders of throughout this subset of the larger community. The Prince Hall Masons and to a lesser extent, the Black Elks, were all noted for their upperclass membership during the 1920s and 1930s.

Social clubs served an interesting role during the Harlem Renaissance in North Omaha. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, these groups—especially women’s clubs—studied, explored and further celebrated Black art, literature and more as part or all of their regular activities. For instance, in a 1928 edition of The Monitor the “Elite Whist Club” announced they “will devote their meetings to a study of the Negro in music, art and literature.” In the same edition, the “Waiters’ Wives’ Art and Social Club” used their third meeting monthly as “art day,” including inviting guests and hosting luncheons as part of their events.

Some of the elite apparatuses in Omaha’s Black community included St. Phillip’s Episcopal Church, which was a recognized upperclass bastion. Other churches played important roles among professionals, including Zion Baptist and St. John’s AME.

Between the two forces of Black social clubs and churches, North Omaha’s professional class countered the racially exclusive Ak-Sar-Ben coronation with the crowning of King Borealis and Queen Aurora starting in 1930 and continuing annually until 1947.

North Omaha had organizations, spaces, places and events for working class people to enjoy the Harlem Renaissance, too. St. Paul Presbyterian Church, a segregated congregation with an activist minister, was one of those spaces. For instance, in 1921, their reports in the papers for more than one Sunday included readings entitled “The Negro in Art and Literature” that were news sharing and teaching sessions as much as anything.

Notable African American artists played in Omaha during this era, too, including singer Paul Robeson (1898-1976) in 1931 and poet Langston Hughes (1901-1967) in 1937, among others. Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872—1906) was a popular African American American poet whose wife, Alice Dunbar Nelson (1873-1935), spoke at Omaha’s segregated YWCA in 1930. Of course, the major Harlem Renaissance painter Aaron Douglas (1899-1979) went to college at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln, and while he didn’t become notable until he went to Harlem in 1925, he surely gained some of his footing from Omaha, which has always been Nebraska’s Black cultural center. Today, Douglas is still referred to as the Harlem Renaissance’s “leading visual artist.”

Some of the things missing from the large scale New Negro Arts and Letters Movement happening in New York City and beyond included the overt declarations of social change popular in many cities. The Omaha Black leadership didn’t pronounce an era of change and weren’t explicitly supportive of what was happening with the younger people. Also, in New York City and beyond there was the phenomenon of the so-called “Negrotarian,” wealthy white people who fiscally supported Black artists and creators. While that crowd was known for coming to concerts in Black-owned venues around 24th and Lake, so far, no account of philanthropy, donations or otherwise has been found in Omaha history from the era. Omaha did have a version of what Wallace Thurman termed the “Niggerati” though. According to Thurman, these were the artists and intellectuals who led the Harlem Renaissance, and in Omaha they included several of the following figures—some of whom were nationally reputed, and others who were local giants on the scene.

Each of these artists influenced the Harlem Renaissance in Omaha, too.

Harlem Renaissance Figures in North Omaha

Throughout the 1920s, there were cultural gatherings in Omaha where African American artists, writers, and intellectuals discussed and promoted the ideas of the Harlem Renaissance. These figures hold the mantel of the era, showing how mixing resistance and rebellion with art and creativity could yield startling social change—even in a city as provincial as Omaha was at the time.

Writing All of the Time

One of the great writers of the Harlem Renaissance, Wallace Thurman (1902—1934), grew up in Omaha’s Near North Side neighborhood, among other places. Along with his most famous work, Blacker the Berry: A Novel of Negro Life (1929), Thurman was also a screenwriter and essayist, a newspaper editor, and a publisher of several short-lived newspapers and literary journals. His influence on the Harlem Renaissance in Omaha and beyond is irrefutable. In addition to his friendships and collaborations with Langston Hughes and others, his impact is still acknowledged today by Black artists including Kendrick Lamar and others. Younger than some of the following North Omaha figures, Thurman undoubtably impacted them and the generations since in the city.

A Poet, Journalist & Historian

George Wells Parker (1882-1931) was a leading figure leading into the Harlem Renaissance in North Omaha. He was a poet, journalist, historian who regularly served as a cultural provocateur in the city and beyond. After graduating from Omaha High School and going to Howard University in Washington, DC for a few years, Parker made his presence known in Omaha in many ways, including as the leader of many civic organizations. As a writer, his early works included an award-winning essay at the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition of 1898, an award-winning essay in the Omaha World-Herald, and journal articles in The Forum, The Literary Digest, and The Voice of the Negro. After a mental health episode left him accused of murder in 1911, he came back to Omaha from Chicago and became an active member of several civic organizations. He led the Omaha Philosophical Society for a few years, and in 1917, founded the Hamitic League of the World, an Afro-centric advocacy organization. Hired as a writer for The Monitor, he wrote influential articles encouraging Black people to move to Omaha from the South. In 1920, he published an Afro-centric history booklet called Children of the Sun. Labeled as “a work that is destined greatly to change the Negro’s outlook upon history as well as his appraisal of himself and his race” by the New York Public Library, the tract was a tour de force touting the predominance of African history in driving the world’s Arts, sciences, governance, economics and more.

Going into the Harlem Renaissance, Parker was a giant force throughout Omaha’s African American community. However, in 1921 he had a falling out with the publisher of The Monitor, and after attempting to helm another paper called The New Era, he tried starting his own newspaper. Called the Omaha Whip, Parker promised to reveal the influence of Ku Klux Klan in Omaha, but after publishing just two editions it folded. Soon afterward he left Omaha for Chicago. After 1925 he fell into obscurity and died in 1931.

A Highly Educated Music Educator

Flora Pinkston (1887-1966) was widely recognized as the most popular and longstanding music teacher in Omaha. After graduating from the New England Conservatory of Music in 1916 and studying at the Paris Conservatoire with Isador Philipp through 1922, she started a 60-plus year career as a private music teacher. Mrs. Pinkston taught voice and piano, theory and harmony. In 1941, the Omaha Star said, “Too much praise cannot be given to Mrs. Pinkston, who is one of Omaha’s most outstanding teachers of music.”

Today, her family home still stands at 2415 North 22nd Street. This house served as a performance and practice studio for her students.

Bringing the World’s Top Entertainers to Omaha

James Jewell (1869-1930) and his wife Cecilia (1882-1946) were already important figures on the Near North Side when they opened the Dreamland Ballroom in 1922. Bringing the first major performance venue to the Black community, the Jewells ran their hired a prominent local architect who designed the family’s apartment and storefronts in the Jewell Building, as well as the Dreamland Ballroom. During its first decade, the hall hosted many notable events including appearances by the nationally famous Black speakers including Roscoe C. Simmons (1881—1951), Rev. Charles S. Williams, Dr. William Pickens (1881-1954), and others, as well as the and the formal launch of the Omaha chapter of Kappa Alpha Psi in 1929.

While it was successful in the 1920s, it wasn’t until 1930 when the father died and his son, Jimmy Jewell took over that the venue really began hopping. Big events and speakers like J. Finley Wilson (1881—1952) still happened, but Jimmy Jewell was especially good at bringing in the hottest musicians from their cross-country trips to play in Omaha’s Black neighborhood. That led Count Basie, Ella Fitzgerald, Duke Ellington, Earl Hines, and Fletcher Henderson to appear. There were also a lot of local favorites including Red Perkins, Nat Towles, Ted Adams, Sam Turner, and Lloyd Hunter among the bands that performed at the Dreamland in the 1920s and 1930s. Nat Towles Creole Harmony Kings was “one of the most talented territory bands” from Omaha, with one academic reporting his band was on par with, if not “superior to the Count Basie Orchestra.”

According to the autobiography of Preston Love, Sr., other bands during the era included Jimmy Jones, Basie Givens, the Synco Hi Hatters, Anna Mae Winburn and the International Sweethearts of Rhythm, Red Rivers and Warren Webb, who performed with the Spiders and the Harlem Aces. Raving about a 1932 performance by Ellington, the Omaha World-Herald noted the spot had both Black and white attendees: “The cream of Darktown’s night life had a mean time—and the fair skinned boys and girls fere brethren under the skin.”

Jewell was robbed of his hall by the federal government during World War II, but afterward ran it for another 35 years. Today it remains, a great legacy of the Harlem Renaissance in North Omaha and surely important as the community moves into the future.

Art and Politics

More than first 70 years of Omaha’s existence, being a Black Democrat was a rarity. For a century, the Democratic Party was the party of enslavers nationwide, and although it was uncommon, it wasn’t impossible to meet Black Democrats in Omaha. In the late 1920s, Andrew Stuart (1878-1937) emerged as a leader among his peers.

After moving from Kansas to Omaha, Stuart opened the Stuart Art Shoppe at 24th and Clark. Featuring supplies for fine arts, the store also sold “the very latest records” and had a “comfortable and up-to-date demonstrating room for the selection of phonographic records,” as well as other race-oriented items including Black dolls, books, postcards and more.

While he never ran for elected office, Stuart stood at the front of the Black Democratic movement. He helped lead the Independent Voters League and the Negro Democratic Club. He was also a founding member of the Depression-era Unemployed Married Men’s Council, which declared, “Today our business and professional men with the assistance of our white friends are using every means at their disposal to bring about a new social trend that will forever enrich the life of this exploited people.” The true transformation of the Democratic Party towards liberalism happened in the 1930s under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Stuart led the charge for him in Omaha’s Black community, as well as promoting Nebraska Legislature candidate Johnny Owens.

When Stuart died in 1937 his shoppe closed immediately, but he’d left his mark and it can be said his legacy of political action continued after him.

The Finest European Cooking for North Omaha

Helen Mahammit (1869-1950), was a leading African American was a chef, teacher and author who ran a catering business from 1905 to 1950. A 1910 graduate of Miss Farmer’s Catering School in Boston, in 1926 she attended Le Cordon Bleu in Paris. Opening the Mahammitt School of Cookery in North Omaha in 1927, she shared 30 years of experience while she taught more than 1,000 students from throughout the Black community.

In 1939, Mrs. Mahammitt independently published Recipes and Domestic Service: The Mahammitt School of Cookery. Focused on French and Russian dishes, she also shared recipes for non-Southern foods to serve while catering events such as weddings, afternoon teas and bridge parties.

She closed her school and business when she retired in 1950. There is no known acknowledgment of her contributions in Omaha today.

Ms. Mahammit’s house—the location of her school—is still standing today at 2116 North 25th Street.

A Religious, Cultural, Civil Rights and Journalistic Force

One of the leading Black creative figures in Omaha for decades, Rev. Dr. John Albert Williams (1866-1933) was an Episcopal minister who dedicated his life to the betterment of African Americans in the city. In addition to pastoring his church for more than 40 years, Rev. Williams started a newspaper, launched the NAACP and participated in many campaigns to improve the religious, social, cultural and economic livelihoods of his friends and neighbors. Before the Harlem Renaissance, he supported the careers of many important cultural figures in North Omaha including George Wells Parker, Lucille Skaggs Edwards (1875-1972), and others.

In the 1920s, Rev. Williams was at the vanguard of Civil Rights in Omaha, ensuring Jesse Hale-Moss’s (c1871-1920) leadership would be successful. With the lynching of Will Brown in 1919, the Omaha NAACP took legs, and after the Tulsa Race Riot obliterated Black Wall Street in 1921, the Omaha chapter raised relief funds for the city’s Black population and hosted refugees. When Rev. Williams became ill in the late 1920s, the chapter floundered.

Many of his other endeavors floundered when he died in 1933, but his impact on the Harlem Renaissance in Omaha is undeniable.

Night Owls and Dixie Ramblers

Frank “Red” Perkins (1890-1976) was one of the leading musicians in North Omaha during the Harlem Renaissance. For a decade before then he was a barnstorming player on the so-called “Chitterlin’ Circuit,” a group of performance spaces throughout the Midwest that were friendly to Black bands. After playing those, Perkins took over a band called the Omaha Night Owls in 1923, and from there forward his career soared. A six-piece, Perkins led the band, played trumpet and sang, and (untruly) earned a reputation as Omaha’s first jazz band. In 1926, he ended that group and formed the Dixie Ramblers. A solid jazz band, they played throughout Nebraska, Kansas, Iowa and North and South Dakota at hotels, ballrooms and theaters, as well as fairs, carnivals and special events. In addition to great music, they had a vibrant stage show with dancing variety acts. During the Great Depression they played regularly in North Omaha, most often at the Dreamland Ballroom. He continued playing in the early 1940s.

Other Black Creators in Omaha

Musicians, teachers, businesspeople and journalists weren’t the only Black creators in Omaha during the 1920s and 1930s. For instance, Omaha artist Paul Gibson drew works for the federal government’s 1939 publication Negroes in Nebraska, and there were other notable Black artists in the city too. The Omaha Monitor reported in 1925 that “the first race girl in Omaha to pose for Negro art exhibit… is Miss Ione Lewis. She is a graduate of the Farnam School and sophomore of Central High School. Miss Lewis is the daughter of Mrs. Effie McClure.”

A study showed that at the end of the 1930s, there were at least 43 Black churches in Omaha. Combining the dedication of those congregations with the energy of the Renaissance led to the emergence of leaders like Rev. John S. Williams of Hillside Presbyterian Church. Rev. Williams was a renowned organizer of a touring gospel group that inspired several other Black churches in Omaha to organize their own groups throughout the 1920s. Other notable choirs in the 1920s and 1930s were at St. John’s AME, Mount Moriah Baptist and Zion Baptist. St. John’s was noted in many newspaper articles during this time for the unusual invitations it received to perform to white congregations throughout Omaha.

There were many Black actors in Omaha during the Harlem Renaissance. Andrew Reed (1893-1939) was a mortician, WWI veteran officer, and community leader who acted in a variety of performances in Omaha during the 1920s and 1930s. The director of the Urban League Little Theater, in the 1910s he was an actor in the “DuBois Dramatic Club” in the old Boyd Theater and an assistant at the Omaha University theater department, too. The YWCA Y Players were a theater group active in Omaha in the 1920s, and during that decade there were several noted productions led by Black people for both Black and white audiences. One particularly noted event was the 1924 production of “A Nautical Knot” by an all-Black cast and production crew at the Brandeis Theatre in downtown Omaha. In 1938, the “Negro Dramatics Club” at Omaha University performed Henrik Ibsen’s Ghost.

In 1926, C.C. Galloway (1890-1958) and two others started The Omaha Guide, a direct competitor to Rev. Williams’ The Monitor. The Guide featured more business news than The Monitor, as well as Black fiction and more. Published through Galloway’s death in 1958, perhaps its most important impact was encouraging the launch of another newspaper in 1938, towards the end of the Harlem Renaissance.

Academic creations were part of the Harlem Renaissance too, and Omaha had its contributors. The leader of the Omaha Urban League for several years, J. Harvey Kerns (1897-1983), was an active academic who studied and wrote about the state’s African American population during the 1930s for his Master’s degree at the University of Omaha. Along with Thomas E. Sullenger, he wrote a paper called “The Negro In Omaha: A Social Study of Negro Development” in 1931 for the Omaha Urban League and Omaha University. In 1937, attorney Harrison Pinkett (1882-1960) wrote a study called A Historical Sketch of the Omaha Negro, and the Works Progress Administration procured the development of The Negroes of Nebraska.

North Omaha’s Jazz Scene Flourished

Jazz, swing, blues and gospel flourished in Omaha during the 1920s and 1930s. So many musicians thrived during the era, including siblings Effie Tyus and Charles Tyus who wrote the music and lyrics for a vocal duet called “Omaha Blues” in 1923. The story of a man who wants to get back to his hometown, the narrator dreams of returning to Omaha to settle down near his parents back at home. He goes on about his love back in Omaha describing her as, “just as sweet as any peach from a tree”. He’s going to get back to the city no matter what, even if he has to walk.

From 1925 through the 1930s, Professor Josiah “P.J.” Waddle kept Omaha’s first-ever all-women’s band called the Waddle’s Ladies Concert Band, and in 1927 a 150-person choir was featured at the community’s annual Emancipation Day celebration.

By the 1920s, there was a lot of competition among jazz bands in the Midwest, and in the 1930s two Omaha bands, Lloyd Hunter’s Serenaders and Red Perkin’s Dixie Ramblers were at the top. The most revered band stop in North Omaha during the 1920s and 1930s was the Dreamland Ballroom. Another important place during that era was Jim Bell’s Club Harlem, complete with “a full line of chorus girls, a twelve-piece orchestra, and imported top-grade comedians, singers, emcees and other acts for the floor show.” It was open from 1933 to 1948.

While both Dan Desdunes and Professor Waddles died by the end of the Renaissance era, future influential jazz figures were born in North during the same time including bandleader Preston Love, Sr. (1921-2004), singer Jeri Southern (1926-1991), trombonist Helen Jones Woods (1923-2020), and percussionist Luigi Waites (1927-2010).

The Black Revolution

Omaha’s Black community had a long history of activism before the Harlem Renaissance, but during that time phenomenal growth happened.

Organizations in North Omaha specifically focused on Black self-reliance established during the Harlem Renaissance included the Omaha Colored Commercial Club (1920), the Cooperative Workers of America Department Store (1921), the Centralized Commonwealth Civic Club (1937), the Negro Old Folks Home (1920) and other ventures were established during this era, while the National Federation of Colored Women had five chapters in Omaha in 1925 under the banner of empowering African American women. The Omaha Urban League opened the Near North Side Community Center in the Webster Telephone Building in 1933, and the American Legion Roosevelt Post 30 bought their building at 24th and Parker that same year.

Omaha’s Civil Rights efforts were propelled forward during the era. Starting in 1921, Rev. Russel Taylor (1871-1933) preached in pulpits across the city against racism and for justice before there was a civil rights movement. Figures such as William Monroe Trotter (1872–1934) in 1921, while Earl Little (1890-1931) and Louise Little (1894-1989) formed the Omaha chapter of W. E. B. DuBois’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) the same year. Later in 1921, the Omaha NAACP began strategically combatting the Omaha KKK. Earl Little’s son was born in Omaha in 1925, and later, as Malcolm X, led the global Black power movement. The Omaha Urban League was organized in 1928, and future Civil Rights Movement leader Whitney Young became its leader in 1929. In 1931, a secretive African American organization called Knights and Daughters of Tabor was established in Omaha.

In 1931, youth activists organized the City Interracial Committee, a youth-led forum that provided activities to churches across Omaha. It operated into the early 1940s. Youth activists continued driving social change in Omaha, and in 1936 the Omaha NAACP Youth Council was formed to lead Civil Rights campaigning. Their work led to integration in several Omaha businesses and their legacy lasts to this day.

Powerhouse Black-Owned Businesses

During the 1920s, I have found that a lot of new Black-owned businesses emerged in the Near North Side. For the first time, broad entertainment venues emerged including nightclubs, mini-golf, ice cream parlors and more. More doctors, lawyers and funeral homes started in the community, as well as stores and hotels operated by African American entrepreneurs.

My research shows that between 1920 and 1939 there were more than 100 Black-owned businesses in the district around 24th and Lake, including more than 40 recorded as starting in those two decades. They included Frank Douglas Shining Parlor (1920), Myers Funeral Home (1921), Tuxedo Billiard Parlor (1923), New Lamar Hotel (1924), J. D. Lewis Mortuary (1927), Apex Billiard Parlor (1928), Hayden’s Market (1932), Broadview Hotel (1932), Club Harlem (1933), Jim Bell’s Harlem (1935), Althouse School of Beauty (1936), Apex Bar (1937), Cotton Club (1938), Swingland Cafe (1938), Lux Barber Shop (1938), Houston Groceries (1938), Johnson Drug Company (1938), E & E Little Diner Cafe (1936), Omaha Outfitting Company (1938), Hall Tailor (1938), Holmes Tailor (1938), Club Harlem Nites (1939), Victory Bowling Alley (1939) and the Thomas Funeral Home (1939). The Omaha Guide newspaper (1926) was also launched, and later the Omaha Star (1938) joined the ranks. There were at least four new doctors offices opened by African American physicians and two Black dentist offices opened near 24th and Lake in the 1920s and 1930s as well. Each of these businesses contributed to North Omaha’s Harlem Renaissance in many ways, and without them the community would’ve been less effective.

One of the longest operating Black-owned businesses in Omaha was launched at the end of the Renaissance in 1938. Mildred Brown and her husband S. Edward Gilbert established the Omaha Star in 1938, and today it is Nebraska’s only African American newspaper. It is easily the greatest legacy of the Harlem Renaissance in Omaha.

Aside from those businesses I specifically call out for their affect on Omaha’s Harlem Renaissance, many other Black entrepreneurs opened shop within the Black community in those decades.

After the Renaissance

The legacy of the Harlem Renaissance in North Omaha continued for decades after, and some would say it’s marks are obvious today, a century later.

When World War II came, thousands of African Americans in North Omaha joined in the war effort. Immediately afterward, new ideas and institutions flourished in the Black community. While the community spirit and sense of racial pride was repressed during the 1930s, a new Black consciousness developed and the community began shifting toward social activism in the late 1940s, heralding the Civil Rights movement in Omaha.

However, it can be argued that none of that would have happened without the Harlem Renaissance in Omaha. For the first time, huge numbers of innovators, organizers, creators and others took footing in the community and made huge strides into the future. That future is still being created in Omaha today, more than a century later.

The Dreamland Plaza was developed in 2003 as an homage to the role of the Jazz era in North Omaha. Hopefully the community will continue recognizing the ways the New Negro Movement shaped and affected people, places and events happening today. The future continues arriving, but will we keep paying attention to the past?

Landmarks of the Harlem Renaissance in Omaha

- Omaha Star offices, 2216 N. 24th St.

- Dreamland Ballroom, 2221 N. 24th St.

- Tuxedo Billiard Parlor, 2221 N. 24th St.

- E & E Little Diner Cafe, 2314 N. 24th St.

- Myers Funeral Home, 2416 N. 22nd St.

- Pinkston School of Music, 2415 N. 22nd St.

- Mahammit School of Cookery, 2116 N. 25th St.

- Broadview Hotel, 2060 Florence Blvd.

You Might Like…

MY ARTICLES ABOUT BLACK HISTORY IN OMAHA

MAIN TOPICS: Before 1850 | Black Heritage Sites | Black Churches | Black Hotels | Segregated Hospitals | Segregated Schools | Black Businesses | Black Politics | Black Newspapers | Black Firefighters | Black Policeman | Black Women | Black Legislators | Black Firsts | Social Clubs | Military Service Members | Sports

EVENTS: Stone Soul Picnic | Native Omahans Day | Congress of Black and White Americans | Harlem Renaissance in North Omaha

RELATED: Enslavement in Nebraska | Underground Railroad in Nebraska | Racist Laws Before 1900 | Race and Racism | Civil Rights Movement | Police Brutality | Redlining

TIMELINES: Racism | Black Politics | Civil Rights | The Last 25 Years

RESOURCES: Book: #OmahaBlackHistory: African American People, Places and Events from the History of Omaha, Nebraska | Bibliography: Omaha Black History Bibliography | Video: “OmahaBlackHistory 1804 to 1930” | Podcast: “Celebrating Black History in Omaha”

MY ARTICLES ABOUT THE HISTORY OF N. 24TH ST.

NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES: 24th and Lake Historic District | Calvin Memorial Presbyterian Church | Carnation Ballroom | Jewell Building | Minne Lusa Historic District | The Omaha Star

NEIGHBORHOODS: Near North Side | Long School | Kellom Heights | Logan Fontenelle Housing Projects | Kountze Place | Saratoga | Miller Park | Minne Lusa

BUSINESSES: 1324 North 24th Street | 24th Street Dairy Queen | 2936 North 24th Street | Jewell Building and Dreamland Ballroom | 3006 Building | Forbes Bakery, Ak-Sar-Ben Bakery, and Royal Bakery | Blue Lion Center | Omaha Star | Hash House | Live Wire Cafe | Metoyer’s BBQ | Fair Deal Cafe | Carter’s Cafe | Carnation Ballroom | Alhambra Theater | Ritz Theater | Suburban Theater | Skeet’s BBQ | Safeway | Bali-Hi Lounge | 9 Center Five-and-Dime | Jensen Building

CHURCHES: Calvin Memorial Presbyterian Church | Pearl Memorial United Methodist Church | Immanuel Baptist Church | Mt Moriah Baptist Church | Bethel AME Church | North 24th Street Worship Center

HOUSES: McCreary Mansion | Gruenig Mansion | Redick Mansion

INTERSECTIONS: 24th and Lake | 24th and Pratt | 24th and Ames | 24th and Fort | Recent History of 24th and Lake | Tour of 24th and Lake

EVENTS: 1898 Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition | 1899 Greater America Exposition | 1913 Easter Sunday Tornado | 1919 Lynching and Riot | 1960s Riots

HOSPITALS: Mercy Hospital | Swedish Covenant | Salvation Army

OTHER: Omaha Driving Park | JFK Rec Center | Omaha University | Creighton University | Bryant Center | Jacobs Hall | Joslyn Hall | Harlem Renaissance

RELATED: A Street of Dreams | Redlining | Black History in Omaha | North Omaha’s Jewish Community | Binney Street | Wirt Street

MY ARTICLES ABOUT CIVIL RIGHTS IN OMAHA

General: History of Racism | Timeline of Racism

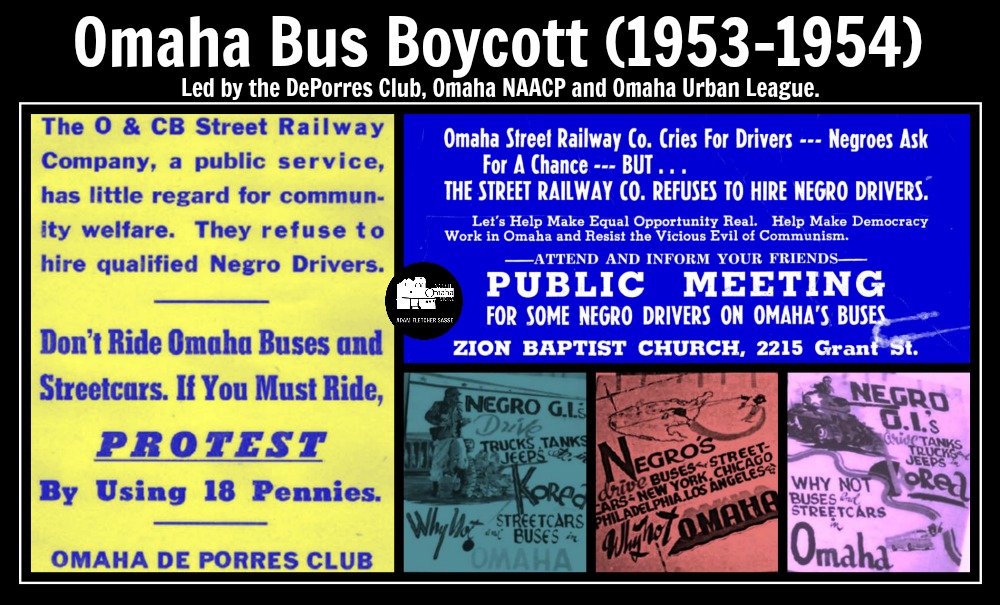

Events: Juneteenth | Malcolm X Day | Congress of White and Colored Americans | George Smith Lynching | Will Brown Lynching | North Omaha Riots | Vivian Strong Murder | Jack Johnson Riot | Omaha Bus Boycott (1952-1954)

Issues: African American Firsts in Omaha | Police Brutality | North Omaha African American Legislators | North Omaha Community Leaders | Segregated Schools | Segregated Hospitals | Segregated Hotels | Segregated Sports | Segregated Businesses | Segregated Churches | Redlining | African American Police | African American Firefighters | Lead Poisoning

People: Rev. Dr. John Albert Williams | Edwin Overall | Harrison J. Pinkett | Vic Walker | Joseph Carr | Rev. Russel Taylor | Dr. Craig Morris | Mildred Brown | Dr. John Singleton | Ernie Chambers | Malcolm X | Dr. Wesley Jones | S. E. Gilbert | Fred Conley |

Organizations: Omaha Colored Commercial Club | Omaha NAACP | Omaha Urban League | 4CL (Citizens Coordinating Committee for Civil Rights) | DePorres Club | Omaha Black Panthers | City Interracial Committee | Providence Hospital | American Legion | Elks Club | Prince Hall Masons | BANTU | Tomorrow’s World Club |

Related: Black History | African American Firsts | A Time for Burning | Omaha KKK | Committee of 5,000

MY ARTICLES ABOUT THE HISTORY OF OMAHA’S NEAR NORTH SIDE

GROUPS: Black People | Jews and African Americans | Jews | Hungarians | Scandinavians | Chinese | Italians

EVENTS: Redlining | North Omaha Riots | Stone Soul Picnic | Native Omaha Days Festival

BUSINESSES: Club Harlem | Dreamland Ballroom | Omaha Star Office | 2621 North 16th Street | Calhoun Hotel | Warden Hotel | Willis Hotel | Broadview Hotel | Carter’s Cafe | Live Wire Cafe | Fair Deal Cafe | Metoyer’s BBQ | Skeet’s | Storz Brewery | 24th Street Dairy Queen | 1324 N. 24th St. | Ritz Theater | Alhambra Theater | 2410 Lake Street | Carver Savings and Loan Association | Blue Lion Center | 9 Center Variety Store | Bali-Hi Lounge

CHURCHES: St. John’s AME Church | Zion Baptist Church | Mt. Moriah Baptist Church | St. Philip Episcopal Church | St. Benedict Catholic Parish | Holy Family Catholic Church | Bethel AME Church | Cleaves Temple CME Church | North 24th Street Worship Center

HOMES: A History of | Logan Fontenelle Housing Projects | The Sherman | The Climmie | Ernie Chambers Court aka Strelow Apartments | Hillcrest Mansion | Governor Saunders Mansion | Memmen Apartments

SCHOOLS: Kellom | Lake | Long | Cass Street | Izard Street | Dodge Street

ORGANIZATIONS: Red Dot Athletic Club | Omaha Colored Baseball League | Omaha Rockets | YMCA | Midwest Athletic Club | Charles Street Bicycle Park | DePorres Club | NWCA | Elks Hall and Iroquois Lodge 92 | American Legion Post #30 | Bryant Resource Center | People’s Hospital | Bryant Center

NEIGHBORHOODS: Long School | Logan Fontenelle Projects | Kellom Heights | Conestoga | 24th and Lake | 20th and Lake | Charles Street Projects

INDIVIDUALS: Edwin Overall | Rev. Russel Taylor | Rev. Anna R. Woodbey | Rev. Dr. John Albert Williams | Rev. John Adams, Sr. | Dr. William W. Peebles | Dr. Craig Morris | Dr. John A. Singleton, DDS | Dr. Aaron M. McMillan | Mildred Brown | Dr. Marguerita Washington | Eugene Skinner | Dr. Matthew O. Ricketts | Helen Mahammitt | Cathy Hughes | Florentine Pinkston | Amos P. Scruggs | Nathaniel Hunter | Bertha Calloway

OTHER: 26th and Lake Streetcar Shop | Webster Telephone Exchange Building | Kellom Pool | Circus Grounds | Ak-Sar-Ben Den | Harlem Renaissance

BASICS OF NORTH OMAHA HISTORY

Intro: Part 1: Before 1885 | Part 2: 1885-1945 | Timeline

People: People | Leaders | Native Americans | African Americans | Jews | Scandinavians | Italians | Chinese | Hungarians

Places: Oldest Places | Hospitals | Schools | Parks | Streets | Houses | Apartments | Neighborhoods | Bakeries | Industries | Restaurants | Churches | Oldest Houses | Higher Education | Boulevards | Railroads | Banks | Theaters |

Events: Native Omaha Days | Stone Soul Picnic | Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition | Greater Omaha Exposition | Congress of White and Black Americans | Harlem Renaissance | Riots

Related Topics: Focus Areas | National Register of Historic Places | Architecture | Museums | Markers | Historic Sites | History Facts | Presentations | History Map

Omaha Topics: Black History | Racism | Bombings | Police Brutality | Black Business | Black Heritage Sites | Redlining

More Info: About the Site | About the Historian | Articles | Podcast | Comics | Bookstore | Services | Donate | Sponsor | Contact

Order A Beginner’s Guide to North Omaha History here »

Sources

- The New Negro Renaissance in Omaha and Lincoln, 1910-1940. Richard M. Breaux.

- African Americans on the Great Plains: An Anthology edited by Bruce A. Glasrud and Charles A. Braithwaite in 2009 and published by University of Nebraska Press.

- NOMA (North Omaha Music and Arts) official website

- “The Black Church in Omaha” by Leo Adam Biga for NOISE in July 2021

- Tom Jack. (1992) Gospel Music in Omaha, Nebraska: A History. University of Wisconsin-Madison.

- Gospel Music Omaha website

- “Preston Love Sr. (Tribute)” by Richie Love

- “North Omaha: The Triple A of Jazz” by Brittney C., Trent H., Cora S., Jennifer Moyer, and Brandon Locke from Making Invisible History Visible, a project of Omaha Public Schools

- “Damned Your Eyes” cover of Etta James by Cynthia Taylor and the All-Blues Band at Love’s Jazz and Arts Center in 2013

- “Preston Love: His voice will not be stilled” by Leo Adam Biga (2010)

- “For the Love of the Music Omaha’s Jazz History,” Making Invisible Histories Visible, Omaha Public Schools (2020)

- “Omaha Blues Sheet Music” (1924) from the History Harvest

- Jennifer Hildebrand, “The New Negro Movement in Lincoln, Nebraska,” Nebraska History 91 (2010): 166-189.

Leave a Reply