Redlining happens when lenders, insurers, landlords and real estate agents steer African Americans or others towards specific parts of a city that are informally or formally segregated. The history of North Omaha includes redlining starting during the 1920s, and being made illegal in the 1960s. This article explores the history of redlining in Omaha.

A Long History of Discrimination

Omaha has a long history of racism. From its earliest years, a group of vigilantes that called themselves the “Omaha Claim Club” made of the city’s recognized founding fathers forced out “undesirable” settlers. While there’s no record of their backgrounds, these unfortunate individuals were undoubtably from countries, languages, families and faiths Omaha’s good ol’ boys didn’t like. Burning out homesteads, lynching, and other forms of terrorism were used by this club for the entire first decade of the city’s history.

This went on, focusing first on Italians, Irish, Czechs and Poles. The Greeks in South Omaha were burnt out of the neighborhood, while the Poles and Irish were set against each other in a fight for a church. Racism and discrimination were evident everywhere in Omaha.

Black in Omaha

After they were settled through the 1870s, the focus turned on a generation of Blacks moving to Omaha from the South. At first wrangled through the dangerous troughs of Omaha’s wide open economic and cultural systems, Southern Blacks became acclimated to the city, starting their own businesses and gaining a foothold.

Early on, living in the Near North Side neighborhood meant living among Blacks, Czechs, Scandinavians, Germans and others. Omaha’s Jewish community was located in North Omaha, with several synagogues, businesses, and other institutions spread throughout the area. Lutherans, Baptists, Methodists and others were all there as well. Long School and others had Americanization classes for all the European immigrants, and the community was a hodgepodge of ethnic and racial identities. Many groups self-segregated, while others were forced into isolation.

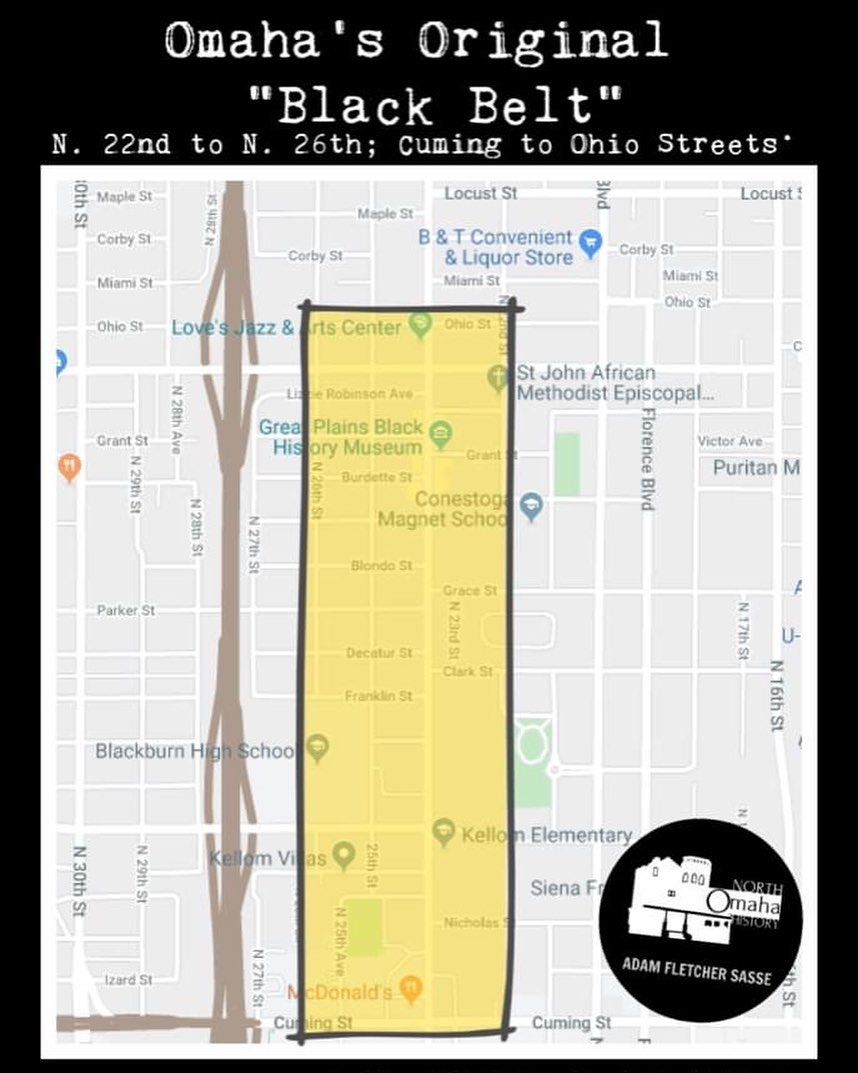

One of those communities was called Omaha’s “Black Belt.”

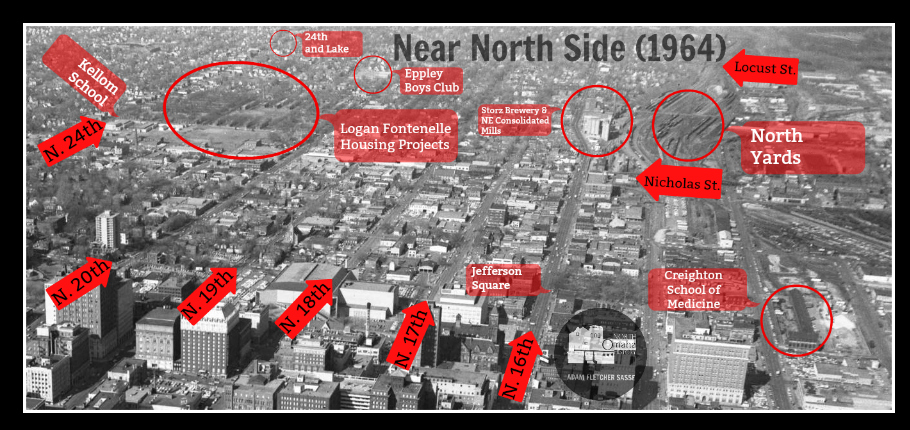

However, despite being isolated – or because of it – Blacks began to flourish in North Omaha. They opened businesses in rented storefronts from Jewish building owners along North 24th, built churches and social halls, created their own institutions and soon began to flourish around Lake Street. By 1920, the Near North Omaha neighborhood was home to an Old Colored Folks Home and the Colored YWCA sponsored a group of Black Red Cross nurses. African American families shopped in Black-owned businesses, attended Black churches, sent students to Black schools, and sent the dead to Black caretakers. [Read Unity in the Community by OPS students.]

They also did business with whites and Jewish people, rented homes from white landlords, and were sometimes allowed to interact with white people in downtown Omaha, despite many businesses having signs in their windows reading “No Negroes Allowed.”

Hatred Becomes Obvious

When it became obvious to the city’s white establishment that new Black doctors, lawyers and other professionals were going to succeed, they took careful steps to ensure Blacks would stay in one place and not threaten the white business foundation.

At first it was mere economic neglect after the 1913 tornado tore through much of the Black neighborhood. Businesses, houses and other institutions were never rebuilt, while white peoples’ churches and social halls took the opportunity to leave the neighborhood permanently.

Tom Dennison was Omaha’s political boss, largely responsible for getting people elected onto city council for more than 30 years. He also controlled the mayor, who for much of his reign over Omaha was “Cowboy” Jim Dahlman. Dennison, called the Old Grey Wolf, controlled the so-called Sporting District, where the sports were gambling, drinking and prostitution. He was the master criminal and crime boss of the city, too.

As early as 1890, he might have caused Omaha’s first recorded lynching of a Black man. He may have orchestrated the white riots that threatened the Near North Side in 1909. There’s no end to what he might have done.

What we know for sure is that in 1918, Dennison’s mayoral candidate, Dahlman, lost to a reformer named Edward Smith. A year later, Dennison orchestrated a race riot of 20,000 people which culminated in the lynching of an African American, the near lynching of Smith, and the almost total destruction of the new county court, finished only two years earlier. Two people were charged for this act of wanton violence, and neither of them was Dennison. However, two years later Dahlman was re-elected as mayor.

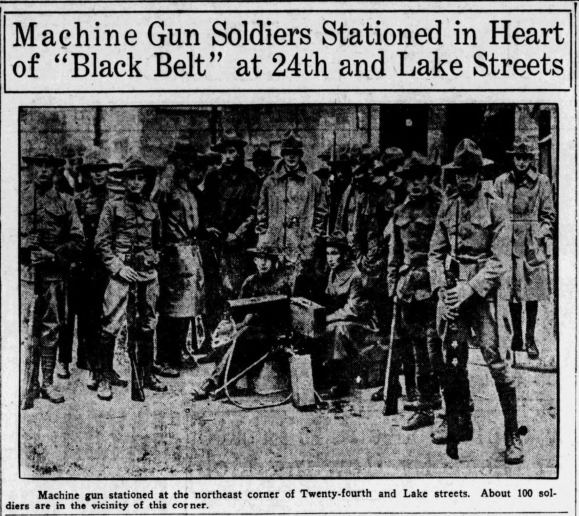

The mob had turned to the Near North Side neighborhood in order to bring their hatred of Blacks to bear on the commercial, social and cultural success there. However, they were met by heavy machine guns and troops from North Omaha’s Fort Omaha, and failed to cause any significant physical damage. However, this was the beginning of official segregation in Omaha’s housing: the Army commanding blacks to stay within a specific area where they could protect them, and that area become red lined. According to one researcher,

“This protective isolation was enacted only for temporary safety reasons; however, it quickly became a type of martial law where African Americans were restricted to the Near North Side neighborhood.”

Sharra L. Montag (2015) “A Game of Roads: The North Omaha Freeway and Historic Near North Side”

This hatred continue to strike at the Near North Side. For instance, in 1926 the home of Malcolm Little, a child growing up on Pinkney Street, was burnt to the ground by the KKK. Young Malcolm’s father was a Black advocate, and upset the white power structure in the city. The child grew up to become a leader of the Civil Rights Movement in the United States called Malcolm X.

Drawing Lines

After the riots of 1919, the Near North Side were made completely segregated.

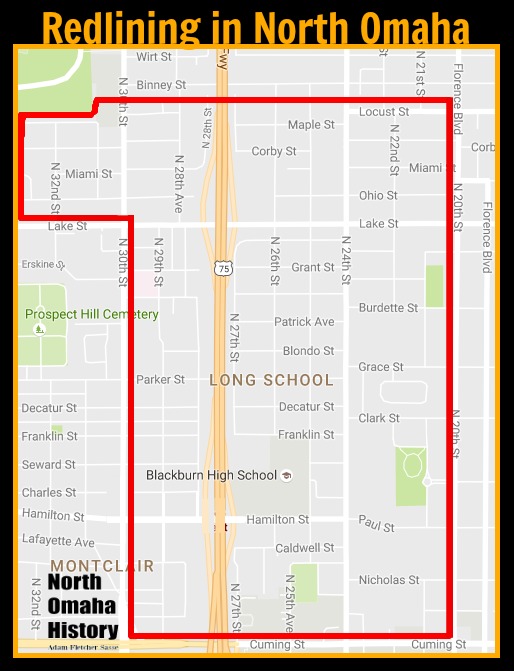

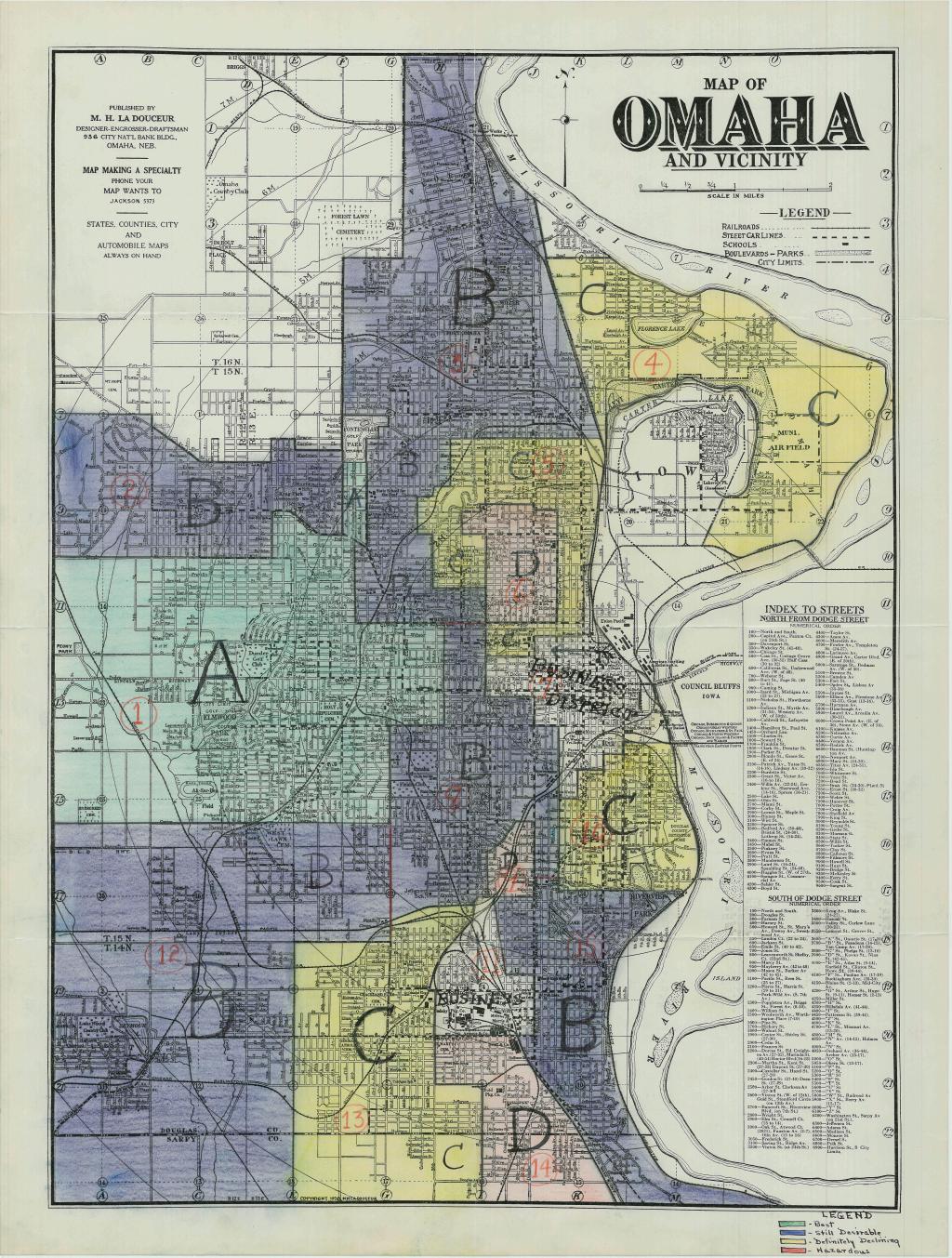

Red lining prohibited Blacks from living south of Cuming Street or north of Locust, so they made the most of their neighborhood. (Special thanks to Professor Palma Strand at Creighton University for sharing the HOLC map at the top of this article!) However, the tactics for getting whites out of those neighborhoods and keeping African Americans from other neighborhoods weren’t so clear.

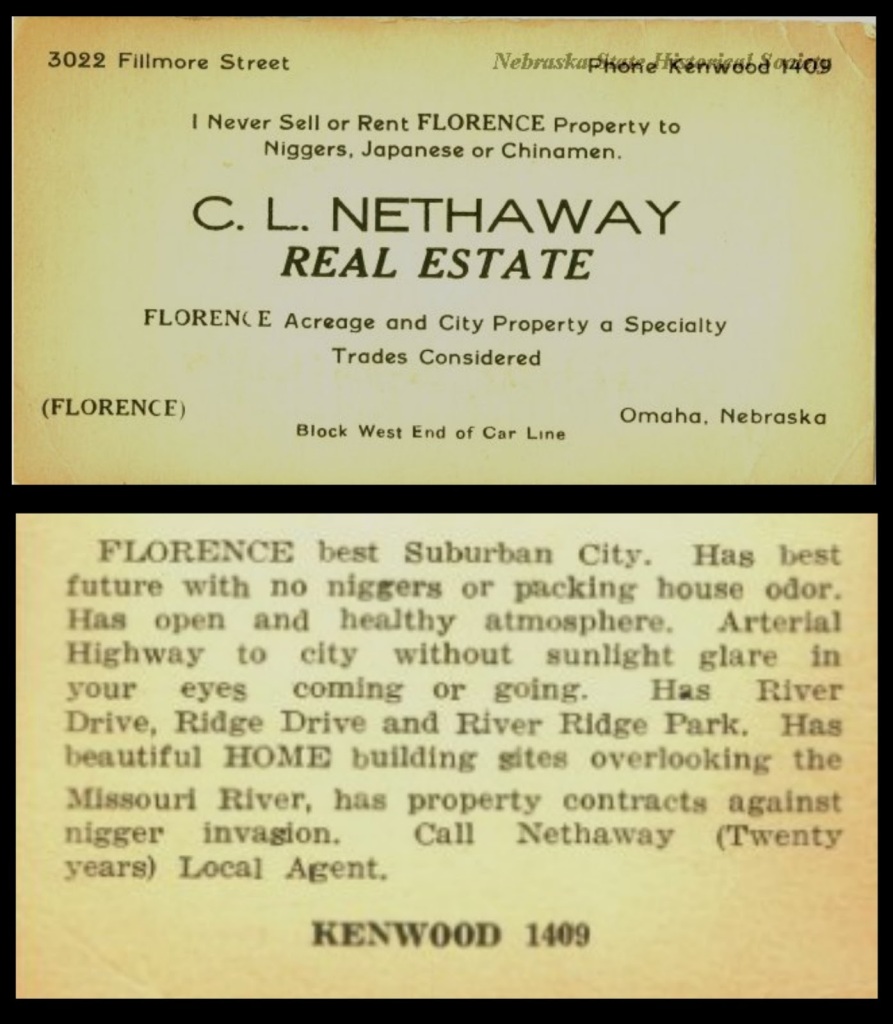

Using racism to scare white Omahans, real estate agents and politicians agreed on an informal system of segregation called red lining. Deciding where Blacks could live and where they could not live, they went office to office among the city’s real estate industry and drew red lines on maps of the city. Within those boundaries, houses and businesses could be owned and rented to Blacks. Outside, they could not.

Other city services followed suit. The schools within the red lined area became exclusively Black schools, while the streetcars that went through picked up fewer passengers than other neighborhoods. All of this began around 1890, with the full brunt of red lining evident by the 1920s.

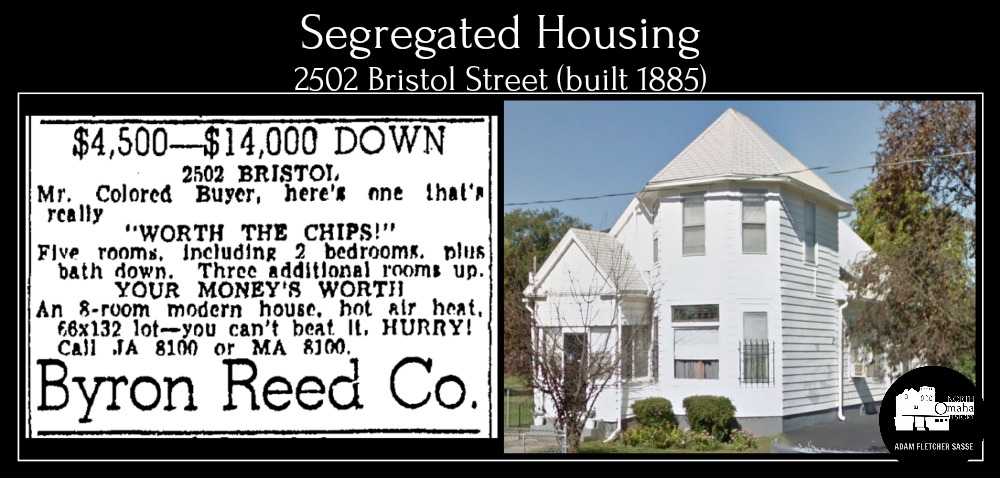

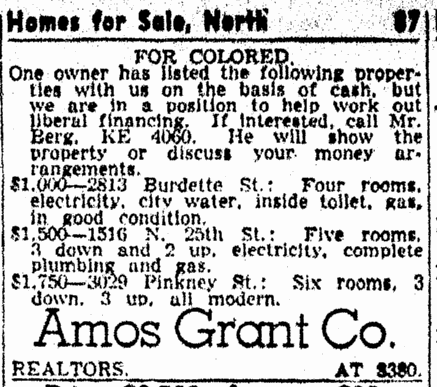

One approach was called blockbusting. Trying to scare people to sell quickly and for cheap, real estate agents would run newspaper ads selling houses and businesses that warned white “The blacks are coming!” This forced housing and commercial property land prices to drop, which were kept low with media hyper-reporting and exaggerating neighborhood crime, which still happens in Omaha.

In 1950, residents of Kountze Place received a mailer saying it was their duty to keep the neighborhood from “a black invasion.” Believing this hate mail, they created a race restrictive covenant prohibiting homeowners from renting or selling to African Americans.

Other industries colluded with red lining tactics. Using the same maps as real estate agents, insurance agents prohibited Blacks from getting homeowners insurance, and kept Black businesses from receiving fair pricing for their policies. Banks did the same by steering Black families to the Near North Omaha neighborhood.

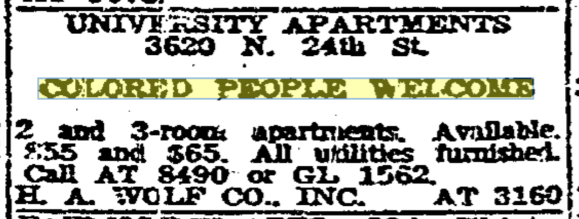

These forces worked together to prevent African Americans from seeing houses outside of Near North Omaha. They used tactics such as fictitious waiting lists, unequal renting and purchasing terms, and charged ridiculously high down payments when purchasing should have cost less. Obvious tactics were used, including advertising “white only” neighborhoods and enforcing race-restrictive covenants. [City of Omaha Human Rights and Relations Commission]

As the trickle of European immigrants to America ceased during the Great Depression, whites started moving out of the Logan Fontenelle Public Housing Projects in Near North Omaha, too. Originally moving to the more westerly Hilltop Projects, HUD eventually bought units in Northwest Omaha, and then moving to mixed income housing. For more than three decades though, public housing in Omaha became synonymous with segregated housing, as whites wouldn’t live there and they weren’t expected to.

This system became more and more entrenched. In 1935, the Federal Housing Administration forced home builders to comply with race-restrictive guidelines, further endorsing the city’s racist policies.

Specific Omaha Neighborhoods that Formerly had Race Restrictions

- Sacred Heart neighborhood

- Gifford Park neighborhood

- Kountze Place neighborhood

- Prospect Hill neighborhood

- Saratoga neighborhood

- Minne Lusa neighborhood

- Miller Park neighborhood

- Monmouth Park neighborhood

Success In Spite of It All

During this period of initial red lining, North 24th Street became a fantastic business district and cultural heart for Near North Omaha. Dozens of businesses owned by Blacks or run by Blacks lined the street, while churches, clubs, saloons, groceries, caretakers, and others went up and down the block. Vibrant foot traffic, cars and buggies, and other signs of life filled the area all of the time. Filled with affordable single family homes, deluxe multifamily apartments and reasonable duplexes, the area did well.

Immediately after World War II, African Americans in Near North Omaha began demanding integration. Struggling hard to challenge the city’s deep-seated racist attitudes and structures, Black protesters began challenging racist red lining policies, while well-meaning white ministers tried integrating their church congregations. Mildred Brown worked with youth activists in the DePorres Club, and Whitney Young led the city’s Urban League to court against Omaha’s discriminatory practices. Change came.

Red lining, blockbusting and other practices were called out, and the system of race-restrictive covenants surrounding Near North Omaha began falling. Bus and street car service began serving the neighborhood more fairly, and the city’s schools committed to ending segregation. In 1963, Peony Park ended their segregation practices, and African Americans were allowed to shop at Crossroads Mall.

However, with the struggle came challenges. In 1966, youth protesting the city’s lack of services to them at N. 24th and Lake began throwing bricks in store windows. BANTU was accused of rallying violence, while Ernie Chambers became involved in stopping other riots. In 1971, two of Omaha’s Black Panther leaders were set up and indicted on murder charges against an Omaha police officer, while another police officer shot an unarmed African American teenage woman in the back. Between 1966 and 1971, many of the Black-owned businesses and seemingly all of the white-owned ones were burnt down along N. 24th.

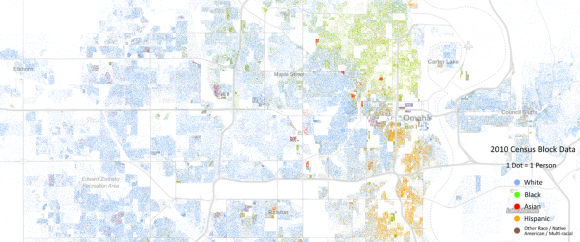

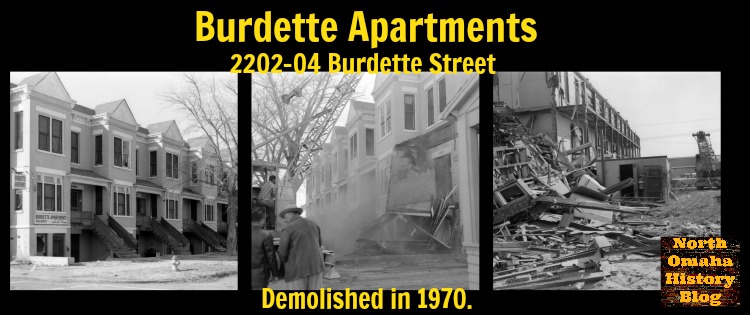

A 1971 analysis of 1970 census data showed there were 389,455 total residents in Douglas County. In the 1960s, the county’s Black population increased from 25,269 to 34,722, and Black people made 8.9% of the total population. The same study showed that less than .5% of the population of Omaha west of North 48th Street was Black, with just one in 35 Black people living west of that street. Dilapidated and vacant houses in North Omaha were quickly bulldozed by the City of Omaha, which seemingly adopted a policy of benign neglect focused on predominately African American neighborhoods in North Omaha. The same 1971 study showed the Near North Side had more than 1,000 fewer houses in 1970 than in the previous census because of that bulldozing. However, other forces caused decreasing amounts of Black homeownership and increasing numbers of white absentee homeownership, ultimately causing the neighborhood to suffer a 72.6% loss in white population with a 30.6% loss in Black residents.

In 1975, the City of Omaha worked with the US Department of Transportation to demolish an entire swath of homes, businesses and other institutions in North Omaha. In building Highway 75, they created a visible “red line” that segregated the community further.

Some things changed, but many did not.

The Present

The City of Omaha adopted a formal “open housing ordinance” in 1969 that effectively ended red lining and race restrictive covenants.

However, the impacts of the history of red lining in North Omaha are still evident. White people didn’t just slowly trickle out of the community; they fled, following a trend called white flight. Working class and middle class whites went to a new band of houses constructed in northwest Omaha and west Omaha between the 1940s and 1970s. White flight led to North Omaha institutions such as Omaha University, Immanuel Hospital and the Poor Clares moving west, while businesses including car dealers and grocery stores simply closed or also moved west.

Red lining didn’t leave quickly. In 1971, Omaha’s school district was brought to court for colluding with real estate companies concerning the location of schools and proposed subdivisions. This showed the district helped create segregated subdivisions, and was judged as evidence of the School district’s general segregationist practices.

Inadequate transportation, insufficient utilities, inappropriately heavy tax burdens, poor maintenance of homes, dysfunctional commercial enterprises, and many other factors ensure that North Omaha remains segregated today. With failing schools, miserable social and cultural conditions and unchecked crime plaguing many neighborhoods, the entire North Omaha community is continually trodden upon by the City’s civic leaders.

- There are still empty lots along N. 24th Street from four riots between 1966 and 1971.

- The City of Omaha incentivizes corporate investment throughout all of the rest of the city without an eye towards North Omaha.

- Metro Transit still undersupplies buses throughout North Omaha, where vast numbers of workers have to commute to West Omaha for work, to shop, and for recreation.

- Focused on building new streets in West Omaha, old streets in North Omaha are literally crumbling from the lack of maintenance.

- White flight is still happening right now in far North Omaha, and neighborhoods where African Americans are moving into for the first time today are feeling threatened by their presence.

- Token sewage updating projects along N. 24th and N. 30th are expected to placate community concerns, while parks, street lights, and law enforcement dwindles throughout the area.

- And African Americans are routinely, systematically and intentionally targeted by segregationist policies, racist practices, and discriminatory beliefs by whites throughout the entire city. Not every white and not all the time – but every African American in the vast majority of circumstances.

Since I was a teen in North Omaha in the 1980s, there have been several plans to revitalize the community. Many focused on business and employment as the answer, while some included churches and schools. Today, the most popular plans connect all those dots, along with strong families, healthy environments and safe neighborhoods. However, just in the last five years little has happened, and North Omaha is unsure whether the cycle of broken promises will ever stop.

In the meantime, gang violence, drug use and a lot of other crime is ravishing goodwill and high sentiment among optimistic Omaha. It looks like the career of Senator Chambers is wrapping up without a lot of other significant leaders stepping forward. Those that do seem entrenched in moneymaking schemes and exploiting the hope of people who need better.

The Future

There’s no clear path to the future for racial integration in Omaha. As the predominant economic, political and social power holders in the city, it is apparent that white people in Omaha do not want to live next door to African Americans. However, since no red lining is better than any red lining, maybe we should simply celebrate the progress that’s been made since it did exist.

The Omaha metro area is in the top 50 most segregated cities in the United States. It should also be noted that lending companies, mortgage agents, banks and real estate agents still practice a form of red lining through the delineation of entire neighborhoods’ values.

Reflecting the rest of the city’s reality, schools in Omaha are highly segregated today. With a hiring disparity noted started in the 1950s, Omaha Public Schools still predominately hire white teachers. School busing to promote integration was forced on the city by the federal government beginning in 1976. The city’s school district won a court decision in 1999 to end it. Many Omahans feel good about the racial makeup of Omaha schools. However, as a recent article states, “School segregation is much bigger than a few schools in the South.”

Today, a popular real estate tool for real estate agents in Omaha describes the lowest favorability for a neighborhood:

“Red areas represent those neighborhoods in which the things that are now taking place in the Yellow neighborhoods, have already happened. They are characterized by detrimental influences in a pronounced degree, undesirable population or infiltration of it. Low percentage of home ownership, very poor maintenance and often vandalism prevail. Unstable incomes of the people and difficult collections are usually prevalent. The areas are broader than the so-called slum districts. Some mortgage lenders may refuse to make loans in these neighborhoods and other will lend only on a conservative basis.”

Sounds like North O, doesn’t it?

You Might Like…

- A History of Segregated Hospitals in Omaha

- A History of Racism in Omaha

- A History of African American Politics in North Omaha

- A History of Black-Owned Hotels in Omaha

- A History of Black Churches in Omaha

- A History of Segregated Schools in Omaha

MY ARTICLES ABOUT CIVIL RIGHTS IN OMAHA

General: History of Racism | Timeline of Racism

Events: Juneteenth | Malcolm X Day | Congress of White and Colored Americans | George Smith Lynching | Will Brown Lynching | North Omaha Riots | Vivian Strong Murder | Jack Johnson Riot

Issues: African American Firsts in Omaha | Police Brutality | North Omaha African American Legislators | North Omaha Community Leaders | Segregated Schools | Segregated Hospitals | Segregated Hotels | Segregated Sports | Segregated Businesses | Segregated Churches | Redlining | African American Police | African American Firefighters | Lead Poisoning

People: Rev. Dr. John Albert Williams | Edwin Overall | Harrison J. Pinkett | Vic Walker | Joseph Carr | Rev. Russel Taylor | Dr. Craig Morris | Mildred Brown | Dr. John Singleton | Ernie Chambers | Malcolm X

Organizations: Omaha Colored Commercial Club | Omaha NAACP | Omaha Urban League | 4CL (Citizens Coordinating Committee for Civil Rights) | DePorres Club | Omaha Black Panthers | City Interracial Committee | Providence Hospital | American Legion | Elks Club | Prince Hall Masons | BANTU

Related: Black History | African American Firsts | A Time for Burning | Omaha KKK | Committee of 5,000

MY ARTICLES ON THE HISTORY OF ARCHITECTURE IN NORTH OMAHA

GENERAL: Architectural Gems | The Oldest House | The Oldest Places

PLACES: Mansions and Estates | Apartments | Churches | Public Housing | Houses | Commercial Buildings | Hotels | Victorian Houses

PEOPLE: ‘Cap’ Clarence Wigington | Everett S. Dodds | Jacob Maag | George F. Shepard | John F. Bloom

HISTORIC HOUSES: Mergen House | Hoyer House | North Omaha’s Sod House | James C. Mitchell House | Charles Storz House | George F. Shepard House | 2902 N. 25th St. | 6327 Florence Blvd. | 1618 Emmet St. | John E. Reagan House

PUBLIC HOUSING: Logan Fontenelle | Spencer Street | Hilltop | Pleasantview | Myott Park aka Wintergreen

NORMAL HOUSES: 3155 Meredith Ave. | 5815 Florence Blvd. | 2936 N. 24th St. | 6711 N. 31st Ave. | 3210 N. 21st St. | 4517 Browne St. | 5833 Florence Blvd. | 1922 Wirt St. | 3467 N. 42nd St. | 5504 Kansas Ave. | Lost Blue Windows House | House of Tomorrow | 2003 Pinkney Street

HISTORIC APARTMENTS: Historic Apartments | Ernie Chambers Court, aka Strehlow Terrace | The Sherman Apartments | Logan Fontenelle Housing Projects | Spencer Street Projects | Hilltop Projects | Pleasantview Projects | Memmen Apartments | The Sherman | The Climmie | University Apartments | Campion House

MANSIONS & ESTATES: Hillcrest Mansion | Burkenroad House aka Broadview Hotel aka Trimble Castle | McCreary Mansion | Parker Estate | J. J. Brown Mansion | Poppleton Estate | Rome Miller Mansion | Redick Mansion | Thomas Mansion | John E. Reagan House | Brandeis Country Home | Bailey Residence | Lantry – Thompson Mansion | McLain Mansion | Stroud Mansion | Anna Wilson’s Mansion | Zabriskie Mansion | The Governor’s Estate | Count Creighton House | John P. Bay House | Mercer Mansion | Hunt Mansion

COMMERCIAL BUILDINGS: 4426 Florence Blvd. | 2410 Lake St. | 26th and Lake Streetcar Shop | 1324 N. 24th St. | 2936 N. 24th St. | 5901 N. 30th St. | 4402 Florence Blvd. | 4225 Florence Blvd. | 3702 N. 16th St. | House of Hope | Drive-In Restaurants

RELATED: Redlining | Neighborhoods | Streets | Streetcars | Churches | Schools

Elsewhere Online

- “Homeowner Insurance in Omaha and the Fair Housing Act: Seeds of Redlining: A Legal Analysis” by the Center for Public Affairs Research at the University of Nebraska Omaha

- “Economic Justice Issues in Omaha: Voting and the Wealth Gap; Economic Justice in Pharmacy Pricing; Economic Justice In Grocery Retailing; Economic Justice in Banking; Economic Justice in Auto Insurance; Digital Divide“

- Learn a lot about redlining, segregation and the struggle for social justice in Amy Helene Forss’s 2014 book, Omaha from Black Print with a White Carnation: Mildred Brown and the Omaha Star Newspaper, 1938-1989.

- For a spectacular exploration of this topic, I recommend Montag, S.L. (2015) A Game of Roads: The North Omaha Freeway and the Historic Near North Side. A graduate thesis for Creighton University.

- “Omaha Redlining Resource Guide” by NOISE

BONUS PICS

Leave a comment