Sometimes ideas don’t work. Developed as a large public housing complex tucked away in suburban North Omaha, the apartments were created as idealized community living. It was a failed idea. This is a history of the Wintergreen Apartments, originally called the Myott Park Housing Complex or “The Myotts,” once located in North Omaha.

A Remarkable Design

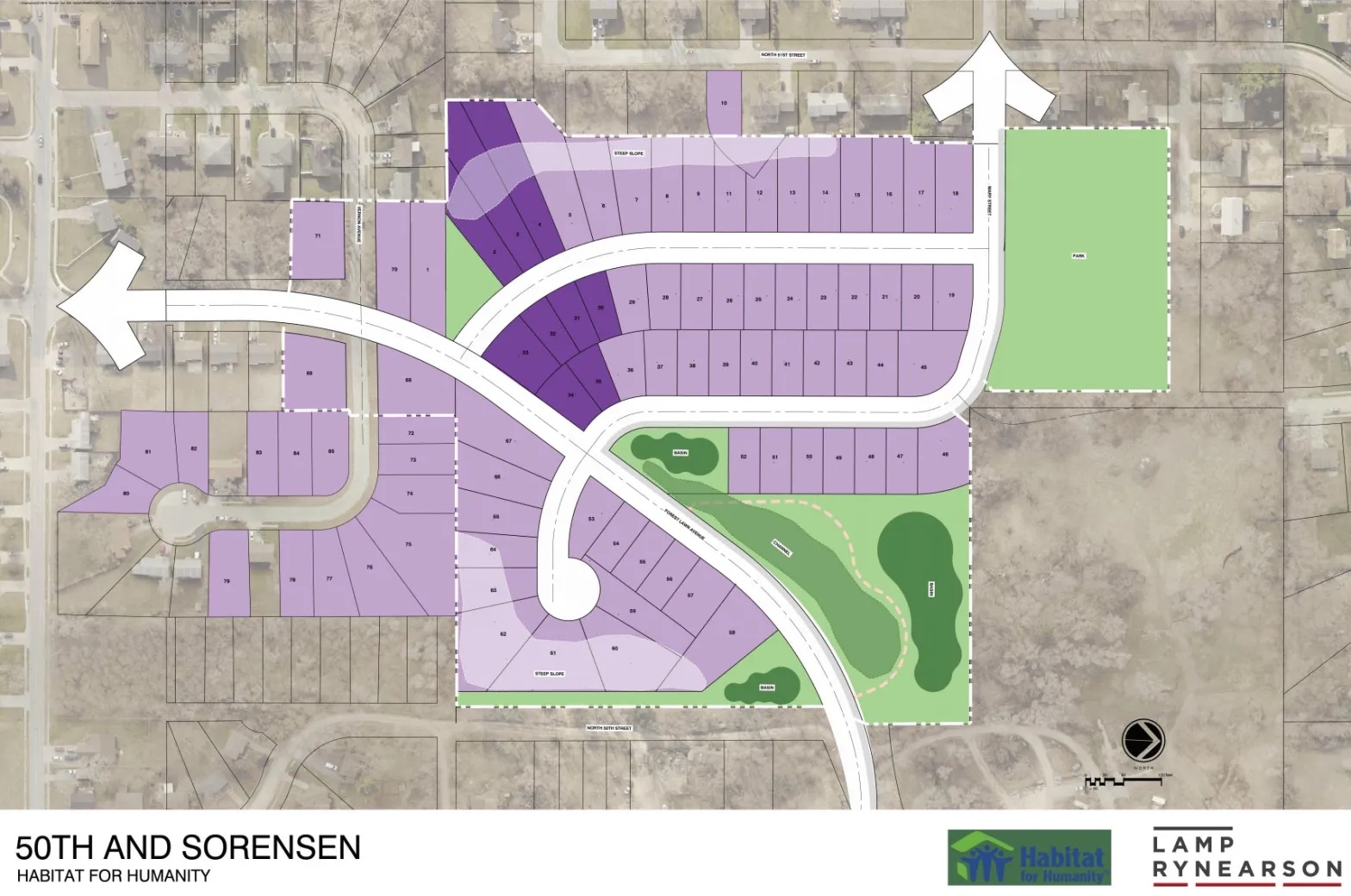

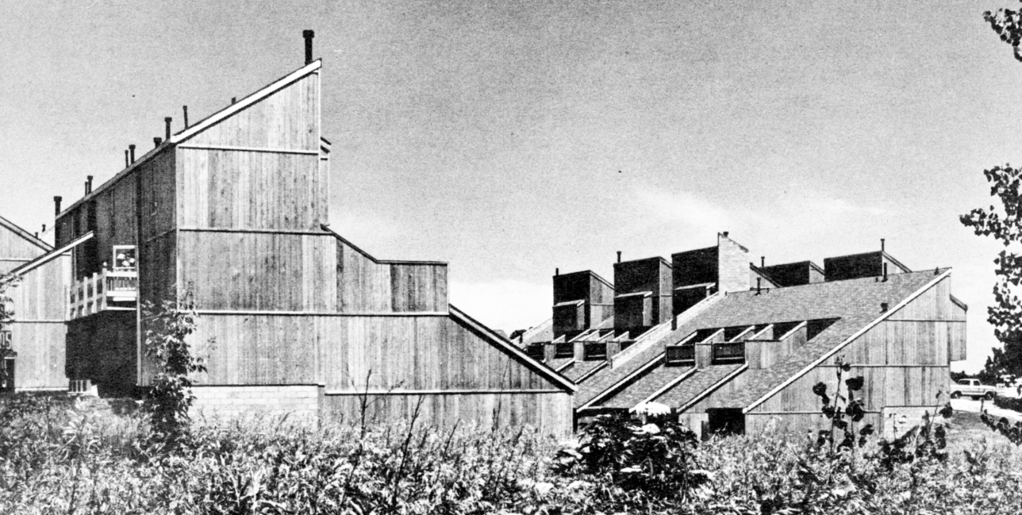

Between 1973 and 1975, a large public housing complex was built at North 51st and Curtis Avenue. Originally called Myott Park Housing, it was located in a sprawling suburban neighborhood. The 583,450 square foot complex was developed on a nearly 14-acre property at the address 6636 North 51st Plaza. Designed by Omaha architect Neil LaMonte Astle (1933-2000), the buildings used a wooden exterior style with sharp angles and moderating building heights to conform to the land and offer non-offensive visual cues. Because of the crowning effect of the apartments, they were called “Astle’s Castle” by a national architectural magazine. According to Omaha Magazine, Astle’s work was featured in The New York Times and Architectural Digest, and “his local homes and buildings remain architectural treasures in the Omaha metro.”

The idealism in the design was in in the architect’s plans. It was intended to be a mixed-income complex that would have both public housing and private units, “with the hope that the community will be totally integrated, socially and economically.” There were stairs throughout the indoors of the apartments that caused people to move past others, and a “community house” in the middle of the complex that had meeting rooms, a day care center and offices.

The complex was remarkable for several reasons. First, as opposed to the other public housing projects in Omaha to that point, they were built out of wood. Rather than being developed as tall towers like several of Omaha’s projects like Hilltop, or as sprawling complexes like Logan Fontenelle or Spencer Street, the 219 apartments at Myott Park was built “up to five stories in height,” but “no unit is more than one stair flight, up or down, from ground level because of the way the buildings are sited on the undulating land.” The buildings were uniquely terraced to conform to the hillsides they sat on, also. Built facing inward, there was a square parking lot surrounding the entire complex. Originally intended to be made with prefabricated walls, the development of the complex forced rush building with 28 wood frame buildings on concrete foundations. Featuring red cedar plywood exteriors, each apartment had a high cathedral ceiling and wide windows that opened onto a large redwood deck. In some apartments, one room opened onto the deck; in others, three rooms did.

Built and originally operated by a private company called the Midlands Corporation based in Council Bluffs, the company obtained Section 236 funding from the federal government with low interest rates. The designer, Neil Astle, said “the ‘physical environment’ is such that it ‘allows interaction’ among the residents.”

The apartments were built outside Omaha city limits and were under the jurisdiction of Douglas County for almost a decade after they were completed.

A Failed Experiment

In a 1974 World-Herald article, Myott Park was described as “a social experiment” because of the income disparities among residents. Some people lived there for its affordability; others because of its design. The paper called it “a unique and appealing alternative to former stereotyped government housing.” The apartments were available to rent for people of “varying economic, social and racial backgrounds.” Rental rates were set according to income levels. That year in 1974, about half the residents were Black and half were white. The company used a recruiter to secure a mixture of tenants, and when they moved in there were efforts made to avoid racial or age-based segregation throughout the complex. Less than a year after it opened, the management declared Myott Park as an experiment “is working, with a little extra time. I don’t expect it to get worse; it can only get better.”

The Douglas County Assessor’s Office reduced the value of Myott Park by $1.2million in 1976. Several area complexes faced the same devaluation. When a neighborhood group called the Northwest Development Council opposed the development of more Omaha Housing Authority rent-subsidized housing in 1977, they cited the existence of Myott Park a mere four blocks away. They claimed “subsidized housing units tend to downgrade a neighborhood when they are placed in new areas. The areas in which the OHA units are planned already have a great many subsidized units at Myott Park…” That housing project plan was eventually scraped because of the protests. In 1978, the complex was brought up in community protests against public housing that happened in Omaha, even though it wasn’t originally a HUD or OHA project.

The NP Dodge Company took over management of Myott Park in 1977. Under direction of the US Department of Housing and Urban Design, or HUD, the units became exclusively available to low-income families.

Problems at the complex started getting broadcast in the media starting in 1978. In an expose on Myott park in April, the newspaper shared comments from several people identified by their race and ago. A “middle-aged Black woman” said that “one of the biggest problems is the disrespect some of the tenants have for other peoples’ property.” A “middle-aged white woman” complained about the “high density of kids of Myott Park” who wrecked Northhampton Mall. “Stores were forced out because they couldn’t handle the damage Myott Park is an example of bad planning.” Other complaints included vandalism, traffic conditions, police visits, ambulances, and a security guard at the nearby Safeway. Another nearby neighbor said, “The problem is there are too many people living there.”

By 1979, the government was becoming more involved in the administration of the complex. That January, the Douglas County Board took steps to install streetlights and sidewalks at the facility. Faced with nearly constant criticism that there was only one driveway into Myott Park and one driveway out, this was an attempt to make walking there easier and safer. That year, the World-Herald reported that Myott Park was criticized to the Omaha City Council more than any other public housing project in Omaha. The newspaper also ran an article highlighting problems one renter had with leaks in her ceiling, citing more than 20 of them over her living room that caused mushrooms to grow in her carpet. Apparently, the roofing of the complex was deteriorating faster than anticipated, leaving residents with substantial damage to their homes and property. NP Dodge said the problems would be fixed as soon as the weather got better. Later that year, a feature on latch-key kids in the newspaper said there were 500 kids under the age of 18 living in the apartments, “the majority coming from single parent households.” The Douglas County Assessor’s Office cut $760,000 from the apartments’ value in 1979, leaving them at $3.1million for the 219 units.

Graffiti of the letters KKK showed up at the apartments in 1980. The Douglas County Sheriff’s Office investigated, but no follow-up report was made in the media.

“Myott Park was an ill-conceived project of a private developer, not OHA…”

James Hanry, executive director of the Omaha Housing Authority, February 25, 1981

In 1981, the principal of nearby Wakonda Elementary School criticized the apartments. “It was going to be a model, there was going to be a racial balance. It never worked.” According to statistics that year, 108 of the 111 children attending Wakonda from Myott Park were Black. The newspaper reported, “Myott Park’s developers… truly wanted an integrated apartment complex… They couldn’t project what would happen and neither could anyone else.” That year, the apartments became a lightning rod for criticism of Omaha Public Schools when the white families around Wakonda started complaining about Black students from the complex. “Wakonda shifted from majority-white to more than 70 percent Black within a few years of the 1973 opening of the federally assisted Myott Park…” The executive director of the Omaha Housing Authority was quoted saying, “Myott Park was an ill-conceived project of a private developer, not OHA…”

In 1983, the City of Omaha formally annexed the apartments. That year the complex was valued at $2.6million and had 617 residents.

In 1990, the media reported on rival gangs using the apartments as “a battleground in a turf war. Fires, shootings and the wail of emergency sirens were regular occurrences. The laundry facility, located next to the office, was a gathering place for drug deals. A guard shack, a sort of Checkpoint Charlie for those who came and went, was testament to the uncertainty of daily life in the project.”

Green Acres Townhouses Associates in New York bought the apartments in 1991. Renaming the facility the Wintergreen Apartments, a new management company was hired too. A very complimentary article ran in the World-Herald the next year, gushing with good things done to improve the facility. New streetlights, new stair lights, better landscaping, better building care, new paint and many other improvements were welcomed by residents and neighbors. The guard shack came down.

However, whatever gains were made weren’t sustainable and the situation stayed grim. Street crime and police calls increased, and the physical property continued to deteriorate. The apartments were fully renovated in 1996 after HUD committed to improving conditions there. While the physical conditions improved, the social conditions did not.

In 2001, a fire gutted one of the buildings at the complex. The property became privately owned in the early 2000s, and were renamed the Wintergreen Apartments. By 2004, they were bought by an Israeli investor and absentee landlord named Avram Cimerring. With knowledge of conditions there, Cimerring bought them without upgrading security or conducting any significant renovations. That year, an Omaha police captain was quoted as saying, “I’m worried about the condition of the buildings, the condition of the apartments and also resident safety.” According to the Omaha World-Herald, “The apartments were plagued by crime, code violations and other trouble in recent years.” Another time the paper said, “The apartments were ordered vacated and sat open to vandals and arsonists…”

In 2003, the World-Herald sounded a tone introducing inspections at the apartments, saying “From a distance, the Wintergreen Park Apartments look postcard perfect with their modern ski – lodge design and hilly, wooded backdrop.” The article went on to lambast the complex for decaying facilities, poorly up-kept units, and much more when the newspaper joined City inspectors and others on a tour. “The inspection sweep followed weeks of complaints from neighbors and a group of students from the University of Nebraska at Omaha. The students reported code violations as part of a sociology class project.”

Another fire struck the apartments in 2005, and both were ordered to be demolished. In late 2005, Cimmering pleaded no contest to charges stemming from code violations at the apartments. Facing nine citations, his lawyer worked out a deal to plea with the City on four. Cimmering came to court from Israel, and was told by a judge to sell all of his properties in Omaha.

Demolition of the apartment was started in 2006, and by July 2007 the World-Herald reported, “There’s nothing left of the Wintergreen Apartments except the crumbling pavement that once served as parking for the problem-plagued housing complex.”

The City of Omaha floundered in its planning after demolishing the Wintergreen Apartments. In 2007, they announced plans for a new apartment complex, as well as single-family homes or an assisted care facility.

The empty property remained empty for more than 15 years, growing over and becoming a place to dump garbage.

Throughout the course of its existence, the apartment complex suffered many issues:

- White idealism—Well meaning white architects ignoring the realities of African Americans and operating from a place of idealistic optimism rather than confronting the roles of white supremacy in housing, addressing racism in economics or acknowledging different perspectives in planning and implementation

- Poor construction—Despite a significantly innovative design, materials used in the structure were completely inappropriate for their high-impact, low-maintenance usage

- Inadequate management—Trying for years to manufacture community throughout the apartments, management varied over the years in their efficacy and commitment. Sometimes operating more as a social service agency than an apartment management company, other times management was completely detached.

- Prolific violence and drug use—In the 1990s, the apartments were subsumed by the absence of active policing, meaningful social services, or relevant community building. Instead, they were largely consumed by negative factors that were unabated by legal enforcement.

There was no requiem when the complex was demolished.

Redeveloping the Area

After 15 years of sitting empty, in 2021 the City of Omaha sold the property to Habitat for Humanity for $1. Soon after, Habitat announced a $25,000,000 redevelopment project for the site called Bluestem Prairie. Featuring 88 single-family homes, the houses feature either three and five bedrooms in as much as 1,800 square feet, and were expected “to appraise for $175,000-$200,000 apiece.”

The existence of the Myott Park Housing aka “The Myotts” aka Wintergreen Apartments is widely sought to be forgotten by the media and redevelopers. To the families that lived there though, it was a home for a time.

Share your memories in the comments section.

You Might Like…

MY ARTICLES ON THE HISTORY OF ARCHITECTURE IN NORTH OMAHA

GENERAL: Architectural Gems | The Oldest House | The Oldest Places

PLACES: Mansions and Estates | Apartments | Churches | Public Housing | Houses | Commercial Buildings | Hotels | Victorian Houses

PEOPLE: ‘Cap’ Clarence Wigington | Everett S. Dodds | Jacob Maag | George F. Shepard | John F. Bloom

HISTORIC HOUSES: Mergen House | Hoyer House | North Omaha’s Sod House | James C. Mitchell House | Charles Storz House | George F. Shepard House | 2902 N. 25th St. | 6327 Florence Blvd. | 1618 Emmet St. | John E. Reagan House

PUBLIC HOUSING: Logan Fontenelle | Spencer Street | Hilltop | Pleasantview | Myott Park aka Wintergreen

NORMAL HOUSES: 3155 Meredith Ave. | 5815 Florence Blvd. | 2936 N. 24th St. | 6711 N. 31st Ave. | 3210 N. 21st St. | 4517 Browne St. | 5833 Florence Blvd. | 1922 Wirt St. | 3467 N. 42nd St. | 5504 Kansas Ave. | Lost Blue Windows House | House of Tomorrow | 2003 Pinkney Street

HISTORIC APARTMENTS: Historic Apartments | Ernie Chambers Court, aka Strehlow Terrace | The Sherman Apartments | Logan Fontenelle Housing Projects | Spencer Street Projects | Hilltop Projects | Pleasantview Projects | Memmen Apartments | The Sherman | The Climmie | University Apartments | Campion House

MANSIONS & ESTATES: Hillcrest Mansion | Burkenroad House aka Broadview Hotel aka Trimble Castle | McCreary Mansion | Parker Estate | J. J. Brown Mansion | Poppleton Estate | Rome Miller Mansion | Redick Mansion | Thomas Mansion | John E. Reagan House | Brandeis Country Home | Bailey Residence | Lantry – Thompson Mansion | McLain Mansion | Stroud Mansion | Anna Wilson’s Mansion | Zabriskie Mansion | The Governor’s Estate | Count Creighton House | John P. Bay House | Mercer Mansion | Hunt Mansion

COMMERCIAL BUILDINGS: 4426 Florence Blvd. | 2410 Lake St. | 26th and Lake Streetcar Shop | 1324 N. 24th St. | 2936 N. 24th St. | 5901 N. 30th St. | 4402 Florence Blvd. | 4225 Florence Blvd. | 3702 N. 16th St. | House of Hope | Drive-In Restaurants

RELATED: Redlining | Neighborhoods | Streets | Streetcars | Churches | Schools

Elsewhere Online

- “Bluestem Prairie” Omaha Habitat for Humanity website

- “The Street That Almost Never Was…” by OmaBabe, March 20, 2009

- “Habitat Omaha Partners with City of Omaha for Affordable Housing Development,” City of Omaha, May 4, 2021

- “Myott Park Housing (Also Known As The Wintergreen Park Apartments)“, Utah Center for Architecture official website

BONUS

Leave a comment