Moving people throughout a growing city is always a challenge, especially in a car-centric city like Omaha. There will be controversy anytime you remove mobility, severe neighborhoods and promote the benefits of one group over others. In the 1980s, the City of Omaha took a step to make a roadway that faced challenges and controversies with mixed outcomes. This is a history of the Sorensen Parkway in North Omaha.

Planning the Northwest Connector

In the 1890s, the Chicago and Northwestern Railroad (CNW) acquired an 40-year-old railroad that cut through rural Douglas County. The first plans for the Sorensen Parkway as we know it today were developed in 1964. Reaffirmed several times again for the next 11 years, in 1977 the railroad formally abandoned the line.

That year, Douglas County proposed a rails-to-trails project for the old railroad, making it into a bike trail. However, “other plans were made” for it by the City, with a roadway quickly dominating the discussion. The possibility of the Northwest Connector became real.

Saying that “that area of town lacks an east-west connection,” planners for the City jumped on the opportunity to develop the new street. A year later in 1978, Omaha voters approved a citywide bond for new road projects called the Street and Highway Bond Fund, and the initial planning for the development of the roadway began then. Several government agencies were involved in planning the Connector, including the United States Federal Highway Administration; Nebraska Department of Roads; Douglas County; the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and; the City of Omaha. While the City took the lead on all local planning and development, each of the agencies contributed greatly to the project, including the federal government agencies.

Envisioned to tie together northwest Omaha with the North Freeway and with Eppley Airfield, the old railroad gave the City a route for a road “that kept intact most of the homes and businesses along the route.”

The Northwest Connector was originally called the railroad arterial, then referred to in several ways, including the Hartman-Redman Arterial, named after the streets it would replace for a section, and as the Northwest Passage. From the start, the parkway was planned to be more like a city street than a freeway. The initial rationalization for the Connector was three-fold; safer travel for residents, complimenting police, fire and ambulance services, and; more efficient access for outlying areas.

In 1980, the City committed “most of the money” in a $45.8million capital improvement fund dedicated to the construction of the Northwest Connector. Construction began in 1981.

Originally, the six-mile Connector was designed for a 50 mph speed limit, with 20,000 cars expected to use it daily. From almost the beginning, three options were in primary consideration for the layout of the road:

- A four-lane street with a median that was 62 feet wide;

- A five-lane undivided street that was 57 feet wide, and;

- A four-lane undivided street that was 46 feet wide.

The first option was selected. In October of that year the City Planner reiterated that the Connector “would not be a freeway, but a ‘major arterial street’ with a 35mph speed limit.” Featuring limited access, turning lanes and traffic signals all along the route, the Connector would look less like a city street than a limited access highway.

The Arthur Storz Expressway was planned simultaneously, but separately from the Connector. Using mostly federal money for construction, that road started at the northern end of the North Freeway and ran east to Abbott Drive, with construction starting in 1982. In October 1983, the development the expressway was linked to the Sorensen Parkway, with Mayor Mike Boyle using the completion of the parkway being used to rationalize the construction of the expressway.

Other peripheral projects were completed by the City of Omaha in conjunction with the construction of the Sorenson Parkway, too. These included the installation of upgraded sewers for several areas west of North 30th Street, as well as lighting, fiber optics and more.

Support & Opposition

Federal officials, Nebraska state officials, and City of Omaha officials all agreed on the development of the Connector.

Not all of North Omaha stood against the development of the Connector. Lawrence McVoy (1922-1986), longtime leader of the Omaha NAACP, had become a school board member in 1980. He supported the development of the roadway, suggesting “It would benefit the city.” McVoy also stood against the Connector because of Ernie Chambers’ leadership in opposing it. “If Ernie wins this, we’re going to have to get permission from him to go to the toilet.” Another school board member, James Beutel, was in support and went on record saying it would, “spur commercial and residential development which will add to the school district’s tax base.”

“If it means lying down in front of the bulldozers, we’ll be there.”

—Buddy Hogan with Greater Omaha Fair Housing Corporation, September 11, 1981

The development of Sorensen Parkway was closely connected to the further construction of the North Freeway, which was highly controversial and weighed heavily on Omaha’s public conscience. Buddy Hogan, representing the Greater Omaha Fair Housing Corporation, said, “If it means lying down in front of the bulldozers, we’ll be there.” A press conference at the Wesley House in 1981 brought together 20 community-based organizations opposing the North Freeway and the parkway. City Councilman Fred Conley and State Senator Ernie Chambers joined in, with Senator Chambers sharing 4,000 signatures on petitions against the construction. According to the Omaha World-Herald, 50 North Omaha businesses signed a petition against the North Freeway and the parkway, too.

In September 1981, Rev. Wilkinson Harper of the Interdenominational Ministerial Alliance spoke strongly against the construction, saying that if the Sorensen Parkway was built “‘a triangular effect’ will result, causing property in North Omaha to lose value and become readily available for sale. That would ‘neatly tie the north end, the airport and newly revitalized downtown area all together for the benefit of Omahans not living in North Omaha.’”

“If it wasn’t for the North Freeway I don’t think they’d plan to build a northwest connector.”

—Omaha City Councilman Fred Conley, November 18, 1981

The School Board for OPS officially decided not to take a stance on the Connector that year, saying that the matter had no direct impact on the schools and was none of the board’s business.

By this point, opponents frequently referred to the Connector as a freeway.

Also in 1981, history activist Matthew Stelly wrote a letter to the editor protesting the treatment of African Americans by the City of Omaha in regards to the planning for the Connector. Among several other points, Stelly suggested the City Council had, “provided an arena for Omaha whites to feel that they have a voice in those issues that are important to them” while “…the best we [Black people] can get is a ‘mock forum’.”

In late 1981, Councilman Fred Conley was the only opposition to the project, saying “If it wasn’t for the North Freeway I don’t think they’d plan to build a northwest connector.”

In the next few years, neighborhoods west of North 60th Street lined up in support of the Connector, while eastern neighborhoods either didn’t say anything or stood against the development.

In 1984, the owners of two businesses at the eastern end of the parkway spoke up against the City’s rotten offers for their business buildings, which had to be demolished to make room for construction. Central Appliance Service Company at 3026 Larimore Avenue and the Stanley Body Shop at 4816 North 30th Street were both reportedly undercut on the City’s estimates for their buildings, and protested to the newspaper. No word was ever reported on whether they got better deals from the City.

The partners in this project proceeded without heeding much attention to these concerns. Believing they knew better for residents, the City’s attitude in the media came across as bordering on benign neglect and indifference towards criticism.

Alternative Routes

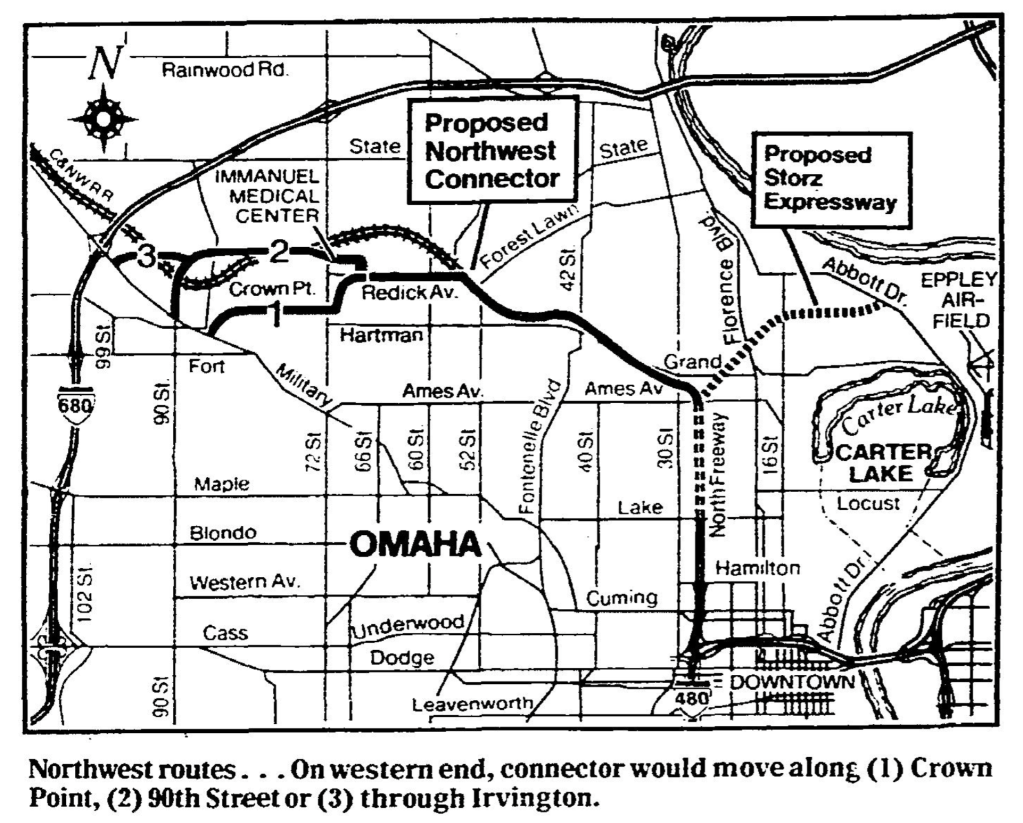

Throughout the years, “as many as eight routes were considered,” with three primary options for routes were considered for the Northwest Connector. All starting at the interchange with North 30th and the North Freeway at Grand Avenue. Each option followed the “Railroad Route” along the old railroad bed to North 56th Street, where plans originally diverged. By 1981, all the route options followed the same route to North 69th Street, were three options were considered:

- Redick Avenue to North 69th Street, then jog south to Hartman Avenue and continued west to intersect with Military Avenue.

- Redick Avenue to spur north to the Immanuel Medical Center, then turn south to join with North 90th Street.

- Follow Option 2 from North 90th to join at Military Avenue near the I-680 interchange.

From the beginning the vision was to connect North 30th with Blair High Road, and from early on the planners did not anticipate it connecting to I-680 because “it is a ‘real problem’ to get a connection on an interstate that is completed.”

In studying the impact of the Connector on the surrounding community, the City of Omaha focused on the area bounded by Ames Avenue and Military Avenue to I-680, and from North 26th Street to North 60th Street.

In 1981, the president of the Central Park Community Council, Bob Arnold, said he didn’t have a preference about which route was taken “as long as a road was built. The road would be for the benefit of the whole North Omaha area.”

Immanuel Medical Center greatly factored into planning for the Connector. When planners proposed cutting through hospital grounds on Newport Avenue, Immanuel’s lawyer immediately went to press to say the route, “will virtually destroy the medical center.” With more than 1,400 employees then, it was one of Omaha’s largest employers and carried sizable pull in politics. “A freeway past a hospital where elderly and ‘people on crutches are walking just doesn’t make sense,’” the Immanuel lawyer was quoted as saying. That quote was interesting because it reveals that although the city swore otherwise, the community saw the Connector as a freeway, and not as a regular city street. However, as opposed to North Omaha leaders, Immanuel’s dissent was summarized by State Senator Dave Newell from Omaha, who said, “I think most people feel we need the road, the question is where to put it.” Of course, Newell was from west Omaha. In September 1981, both the Immanuel Medical Center and the Sperry Vickers Corporation came out the recommended route through the Immanuel campus and past the Vickers plant.

The City approved the final route of the Connector in October 1981, with the newspaper reporting “The recommended route would originate near 30th Street and Ames Avenue, turn northwest, cross the Immanuel Medical Center grounds on Newport Avenue and eventually swing southwest connecting with 90th Street north of Fort Street.” In mid-November 1981, the City Council again approved the creation of the Connector and reiterated the route through the Immanuel Medical Center. Agreeing to negotiate the exact specifications with them, the City forced Immanuel to hire a new lawyer to represent them in the process. In summer 1982, the City and Immanuel agreed on a deal for the Connector to not slice the hospital complex in two, instead moving south of the complex but also forcing the hospital to sell 30 acres to the City.

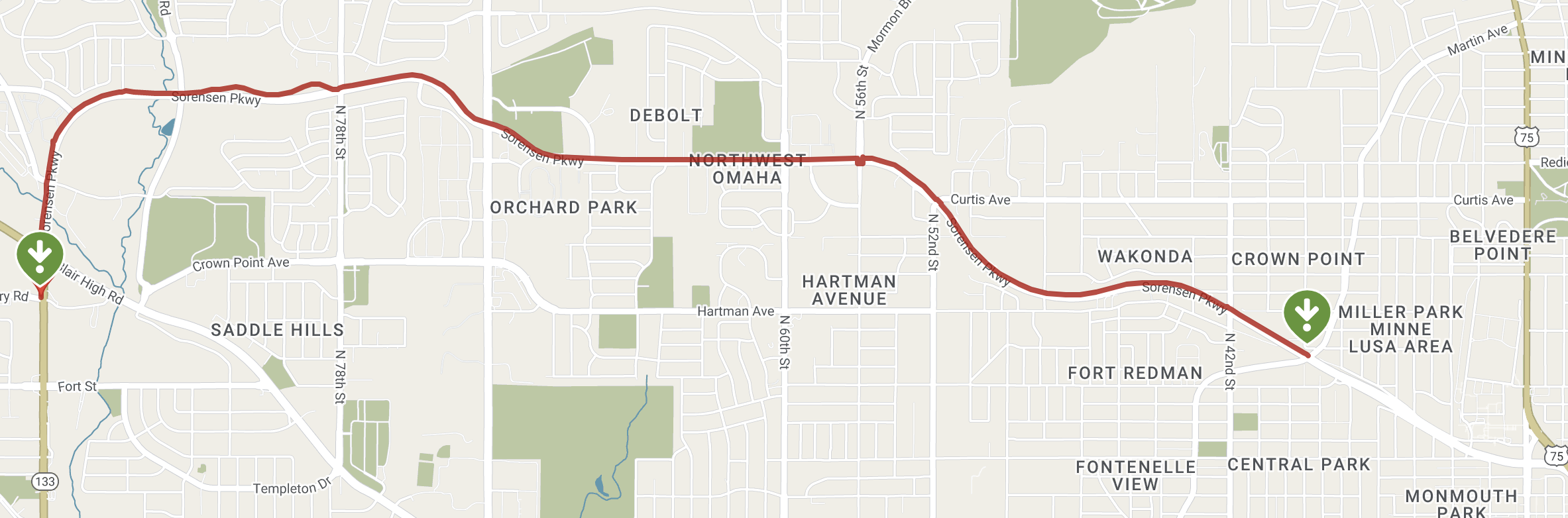

Final design work was completed in fall 1982, and construction was scheduled to begin in 1984. However, several major delays kept the project from moving forward. A 1995 report on the parkway said that North Omaha experienced four construction segments. The first was from North 30th to Fontenelle Boulevard, and from Fontenelle Boulevard to North 42nd Street, and was completed in 1990. The second section was completed in 1991, and ran from North 42nd Street to North 52nd Street. The third section was completed in 1992 from North 52nd to North 56th, and in 1994 the fourth section was completed from North 60th to North 72nd Street.

In April 1999, the Douglas County Board approved the second phase of the Northwest Connector that linked the Sorensen Parkway with Blair High Road. Costing $4,000,000, the 1.9-mile section went from North 72nd Street to North 90th Street, ultimately stopping at the Blair High Road.

Construction

In April 1983, the City Council formally named the Northwest Connector after former Omaha Mayor A.V. Sorensen (1905-1982), referring to it as the A.V. Sorensen Parkway. When he died, Mayor Sorensen was heralded by The New York Times for cleaning up corruption and scandal in the city government and founding the Boys’ Clubs in Omaha.

According to the Omaha World-Herald in 2001, the “City of Omaha built the expressway segment from 30th to 72nd, starting in 1988 and finishing in 1995. It was named for A.V. Sorensen, Omaha mayor from 1965 to 1969. Douglas County built the final segment, starting in 1998.”

For the next several years, media reported on construction progress and hold-ups. They identified new MAT routes opening because of the Parkway, and intersections changing. There were other reports too, most of them glowing.

“I personally apologize for the inconvenience that you all have faced in the past, but patience has paid off.”

—Omaha City Councilmember Lormong Lo, October 19, 1995

However, in 1986 construction was hit by funding delays as costs soared. A county official was quoted as saying “Sorensen Parkway is a ‘highly desirable, but not crucial’ project to the county,” walking back the timeline by several years. By that point, land was graded from North 30th to North 42nd, with sewers installed from 30th to Fontenelle Boulevard.

In 1987, the mayor recommended renaming the parkway after recently deceased former mayor and Nebraska senator Edward Zorinsky. However, the proposal went nowhere and the named stayed the same.

Completing the section from North 56th to North 72nd Street was the final phase of the City’s work on the Parkway. Unable to continue past North 72nd Street, the City’s plans were delayed in 1989 because the County didn’t have plans for completing their section west of North 72nd.

It was 1995 before the City of Omaha poured its last concrete on their section of Sorensen. Its section from North 30th Street to North 72nd was 3.5 miles long. The City’s public works director said then that it took 11 years and $11.5 million to complete the project, which had no federal money in its construction; it was financed entirely by street and sewer bonds approved by voters.

In 1998, the County was explaining away delays on their segment beyond North Omaha and blamed it on funding, even though “federal dollars will pay for 80 percent of the cost” for the County’s section.

Construction Timeline

That was an oversimplification of the process though. The actual project timeline included:

- 1964: Planning begins

- 1977: The City of Omaha acquired the Chicago and Northwestern right-of-way

- 1978: Voters approve the Omaha Street and Highway Bond Fund, which includes funds for the parkway

- 1979: Consultants present the City Council with three potential plans

- 1981: Planning approved for the route from North 30th to North 72nd

- 1982: Immanuel and the City completed a deal for the finishing segment of the route

- 1984: Site preparation began

- 1986: Construction delays announced by the City and County

- 1988: Construction began

- 1995: The City of Omaha completes its section from North 30th to North 72nd Street.

- 2001: The entire Sorensen Parkway was completed and dedicated in October

Adjacent Bike Trail

According to 1981 plans, a walking trail and a bicycle plan were included to the Omaha City Council. In 1983, the City confirmed plans for bike trails to follow the North Freeway and Sorensen Parkway that would “connect the inner city with the two lakes,” in reference to Cunningham and Standing Bear Lakes. Longtime city official Marty Shukert suggested the paths would be developed in 10-20 years. In 1997, the newspaper announced a $20million project that would create bike trails throughout the entire Omaha metro area, including along Sorensen.

The City announced a different multi-million-dollar plan to develop a “Back-to-the-River” bike trail along the Parkway in 1999, with eventual plans to connect Northwest High School to the former ASARCO plant site in downtown Omaha.

As of 2022, the Sorensen Parkway Trail extends from Fontenelle Boulevard to west Omaha. It doe not travel along the first mile of the Parkway from North 30th to Fontenelle Boulevard, and it does not connect with the rest of the City’s trail system, including the new North Omaha Trail, the Missouri River Trail, or other nearby bike trails. The entire trail runs 4.8 miles and is paved the entire distance.

Effects of the Parkway

In North Omaha, studies found that there were almost no environmental impacts for the development of the Connector, as well as no noise or air quality impacts either. The Connector was found to not affect neighborhoods near the pathway, since it “will follow along this natural edge, and not result in neighborhood penetration.” No threatened or endangered animals lived along the route, and there was no significant damage to the prime farmland along the way. The land was already designated for urban development and would have been converted to other uses anyhow.

After a review by the Nebraska State Historical Preservation Officer, “no archeological sites” were found along the route of the Northwest Connector. There were no cultural assets affected either. A 1992 study found there were no landfills, gas stations, laundries or other environmentally sensitive sites along the route. Since the route went along the rail bed through North Omaha, no homes were harmed, and only a barn and one business building were affected.

By early 1982, land surrounding the western reaches of the parkway was going up for sale, with ads indicating that real estate agents anticipated immediate and substantial growth.

According to the 1990 census, “ethnic composition near the Northwest Connector” was 89.5% white; 7.6% Black; 2.2% Asian and Pacific Islander; 0.3% American Indian/Eskimo/Inuit; and .3% Other Races.

Starting in 2006, the Metro Community College began a redevelopment and expansion campaign at Fort Omaha along Sorensen Parkway. Successfully expanding their facilities at North 30th and Sorensen Parkway with more than 250,000 square feet of new buildings, parking and more, the college has invested more than $100,000,000 in their Fort Omaha campus and continues thriving today.

The Omaha Chamber of Commerce announced an economic development strategy in 2006, using the Sorensen Parkway to redefine the northern boundary of North Omaha, with North 16th on the east, North 52nd on the west and Cuming Street on the south. This redefinition of the community’s boundaries reflected the growing role of the parkway in the City’s political and economic development. Economic development along the Parkway has varied though, largely skipping over any area east of North 56th Street and singularly happening to the west. An exception was the redevelopment of a historic shopping building at North 42nd and Redman Avenue into a gas station and convenience store, and the opening of a new $3.5 million Aldi, discount grocery store, at North 30th Street and Sorensen Parkway. Otherwise, the Northampton Mall, a failed 1970s-era shopping center at North 56th and Sorensen Parkway, has been successfully redeveloped into a church and healthcare facility. A discount store was opened at the intersection, too.

The creation of the Sorensen Park Plaza on the southwest corner of North 72nd and Sorensen in 2006 was anchored by a Target store along with other stores opened west of North 72nd Street. In 2006, the media celebrated the economic development at North 72nd and Sorensen, saying it was “bursting with economic development” because of the fast food restaurants and mini-malls being opened there. The opening of Omaha’s first movie theater in this region of Omaha escaped North Omaha too when it opened at North 74th and Sorensen.

In 2007, the Omaha Star labelled the parkway “a modern contribution to the historic park boulevard system.”

By the time it was completed in 2001, the Parkway speed limit was posted at 40mph the entire distance. In 1998, it was projected that “By 2020… between 30,000 and 35,000 vehicles are expected to use the road.” The road carried an estimated 20,000 cars daily in 1995.

As of 2022, no substantial, sustained commercial economic development has happened along Sorensen Parkway east of North 56th Street.

Ongoing Criticisms

Construction of the Parkway doesn’t mean that people stopped caring though.

In 1993, residents near North 50th and Arcadia Avenue complained to the City about the parkway, claiming it was unsafe and needed safety upgrades, and saying it lowered their home values. The City countered and claimed the parkway was designed without flaw and that the construction of the parkway raised their home values. A City official was quoted saying, “There’s no question we created some damage with erosion to several of the back yards… We’ve gone in and cleaned it up and resodded. As far as we’re concerned, the case is closed.” Nothing further happened.

A few years later, the World-Herald announced in an article that, “Unrest in North Omaha Frustration Spills Over Among Blacks,” and included a quote from Mayor Hal Daub listing the completion of the Parkway among successes contrary to the title.

Aside from the existence, acquisition and construction of the Sorensen Parkway, there has been nearly constant criticism of the road since it opened. The City of Omaha and Douglas County have shown little interest in much of the criticism though, and little has changed. It took years for a walking path/bike trail to be completed along the parkway, and landscaping has varied in its maintenance over the years. Between 2001 and 2022, more than 20 reports about the speed limit have been reported in the media. Speaking about the parkway in 2015, City Councilmember Ben Gray was quoted saying, “It’s like they drag race… You can hear tires screeching. People drive it too fast, any time of the day or night.” The Omaha World-Herald ran an article called “A dangerous drive into downtown Omaha,” and disparaged the parkway more than once that year.

Additionally, the parkway was designed and built without shoulders. This has led to nearly countless dangerous circumstances and several crashes because drivers couldn’t get broke-down cars off the roadway.

Few of these concerns have been addressed by the City or any of the partners in the planning and construction of the route.

Sorensen Parkway Landmarks

Today, east of North 72nd Street, the parkway winds through and past many North Omaha landmarks.

Neighborhoods on Sorensen Parkway

There are a dozen neighborhoods along the distance of the parkway. Here are some located east of North 72nd Street.

- Collier Place

- Monmouth Park

- Central Park

- Crown Point

- Wakonda

- Fort/Redman

- DeBolt

- Orchard Park

Historic Places on Sorensen Parkway

In the 1980s, the Nebraska State Historical Society reviewed the planned route of the Northwest Connector and found there were no historical sites affected by its development. However, my own scan found these historic places near Sorensen Parkway.

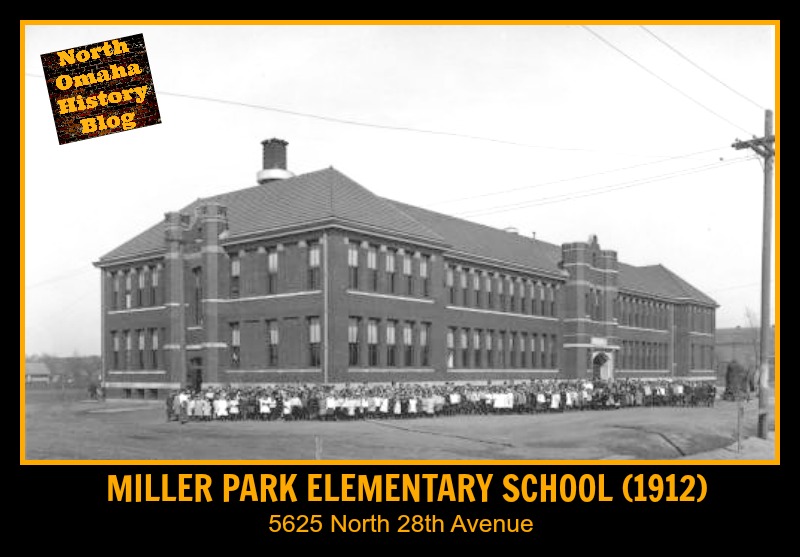

- Fort Omaha National Historic District, North 30th and Sorensen Parkway

- 42nd and Redman Avenue Commercial District

- Golden Hill Cemetery, North 42nd and Browne Street

- Temple Israel Cemetery, North 42nd and Redick Avenue

- Site of the former WOW tower, 5504 Kansas Avenue

- Springwell Danish Cemetery, North 63rd and Hartman Avenue

- Lost town of DeBolt, North 60th and Girard Avenue

- Forgotten town of Irvington, Irvington Road and Sorensen Parkway

Schools near Sorensen Parkway

- Metro Community College, 5300 North 30th Street

- Central Park Elementary School, 4904 North 42nd Street

- Pinewood Elementary School, 6717 North 63rd Street

- Nathan Hale Middle School, 6143 Whitmore Street

- Roncalli Catholic School, 6401 Sorensen Parkway

- Wakonda Elementary School, 4845 Curtis Avenue

Faith Communities Near Sorensen Parkway

There are several faith-based communities along or near Sorensen Parkway too. They include:

- Quoc An Buddhist Temple, 3812 Fort Street

- Kingdom Hall of Jehovah’s Witnesses Adams Park Congregation, 5465 Fontenelle Boulevard

- Kingdom Hall of Jehovah’s Witnesses Benson Park Kingdom Hall, 5911 Ville De Sante Drive

- Trinity Hope Foursquare Church, 4030 Redman Avenue

- Shiloh Church of God and Christ, 5416 Fontenelle Boulevard

- Karen Christian Revival Church, 6010 North 49th Street

- Joy of Life Ministries, 6401 North 56th Street

- Victory Church, 6330 North 56th Street

- Eagles Nest Worship Center, 5775 Sorensen Parkway

- Olive Crest United Methodist Church, 7180 North 60th Street

Recreational places along sorensen parkway

- Sorensen Parkway Trail, Fontenelle Boulevard and Sorensen Parkway

- Crown Point Park, 4384 Laurel Avenue

- Cottonwood Heights Park, 6220 North 51st Avenue Circle

- Orchard Park, North 66th Street and Hartman Avenue

Other Places Along Sorensen Parkway

- CHI Health Immanuel, North 72nd and Sorensen Parkway, including Immanuel Medical Center Treatment Center, CHI Health Clinic Family/Priority Care, CHI Immanuel Conference Center, CHI Health Emergency Center, and more

- Immanuel Pathways PACE® (Program of All-inclusive Care for the Elderly), 5755 Sorensen Parkway

- The Big Garden, North 56th and Read Streets

- Urban Acres Horse Rescue, 4806 Redman Avenue

You Might Like…

- A History of the Intersection of North 42nd and Redman Avenue

- A History of Railroads in North Omaha

- A History of Streets in North Omaha

MY ARTICLES ABOUT THE HISTORY OF STREETS IN NORTH OMAHA

STREETS: 16th Street | 24th Street | Cuming Street | Military Avenue | Saddle Creek Road | Florence Main Street

BOULEVARDS: Florence Boulevard | Fontenelle Boulevard

INTERSECTIONS: 42nd and Redman | 40th and Ames | 40th and Hamilton | 30th and Ames | 24th and Fort | 30th and Fort | 24th and Ames | 24th and Lake | 16th and Locust | 20th and Lake | 45th and Military | 24th and Pratt

STREETCARS: Streetcars | Streetcars in Benson | 26th and Lake Streetcar Barn | 19th and Nicholas Streetcar Barn | Omaha Horse Railway

BRIDGES: Locust Street Viaduct | Nicholas Street Viaduct | Mormon Bridge | Ames Avenue Bridge | Miller Park Bridges

OTHER: North Freeway | Sorenson Parkway | J.J. Pershing Drive | River Drive

Elsewhere Online

- Omaha Northwest Connector (Sorensen Parkway) Construction, Douglas County Environmental Impact Statement by the United States Federal Highway Administration, Nebraska Department of Roads, and Douglas County, Nebraska, with the U.S. Corps of Engineers and the City of Omaha in 1995.

Leave a comment