Adam’s Note: Special thanks to guest writer Michele Wyman for sharing this piece with me to post on NorthOmahaHistory.com. Learn more about her in the bio at the end of the article!

Introduction

Few events in Omaha’s history capture the imagination as much as the Trans Mississippi Exposition of 1898. Dubbed “The White City” by periodicals of the time, the Trans Mississippi Exposition rose from the prairie to dazzle visitors in an attempt to promote not only Omaha, but the regions west of the Mississippi as well, still regarded as frontier by much of the country.

Photographs of the Grand Court show impressive classical buildings surrounding a massive lagoon — a fantastic vision that would be more at home in Europe than the Midwest. When Omahans today first learn of the exposition and see these photos, they often question why it was all torn down. The standard answer given is that the structures of the exposition were never meant to be permanent. While the graceful buildings had the appearance of stone, they were made of timber framing covered with staff (a type of plaster) that could be sculpted to imitate the fine architecture of the classical world at a fraction of the cost and time to build lasting structures.

The Trans Mississippi Exposition was so successful that a group of investors purchased the buildings and control of the expo grounds to host “The Greater America Exposition” the next summer, this time incurring heavy losses. After the close of the second expo the demolition and salvage rights were sold to the Chicago Wrecking Company. Some materials were shipped to Chicago, while other items, such as lumber from the deconstructed buildings, were sold locally. The lagoon, originally intended to remain as an improvement to Kountze Park, and later a smaller lagoon was created.

Today, smaller artifacts such as souvenirs, photographs and written accounts of the expositions remain, and it is assumed that nothing substantial from the exposition survived.

“Sewer Excavation Turns Up Pieces of Omaha’s Glorious Past”

Omaha World Herald, May 24, 1980.

In 1980 a construction worker named Vince Saverino found pieces of plaster that resembled decoration used on buildings at the exposition while digging a sewer trench in Kountze Park. Notifying his superiors, word spread among local historians and preservationists and opened questions about whether more material from the exposition was buried in Kountze Park. The possibility of an excavation was discussed, but not planned. David Murphy, an architect associated with the Douglas County Historical Society, visited the site and stated that more research was needed.

Searching for Artifacts in the Digital Age

Researching history in the present day is so much easier with the internet, digital archives, and online communities of like-minded people to aid in the search. Anyone with a computer and a knack for search queries can become an amateur historian. I came to know Adam Fletcher Sasse, creator of NorthOmahaHistory.com, through Facebook. He posed a challenge to myself and a few other local history buffs — using the internet, an advantage that previous generations of history enthusiasts did not have, could we find evidence of surviving exposition artifacts or buildings?

Loving a good history mystery, I dove into digital archives for the Omaha World Herald and Omaha Bee, searching for anything I could find relating to the Trans Mississippi Exposition. When I felt I exhausted all search queries that might yield useful results, I continued my search at the Omaha Public Library and even contacted city offices and local utility companies for answers.

After months of searching, I was able to piece together the story of two fantastic structures of the exposition that were designed as a tribute to Omaha’s own glorious fair, and how they were lost and forgotten, rediscovered, and tragically, lost again.

A Permanent Memorial

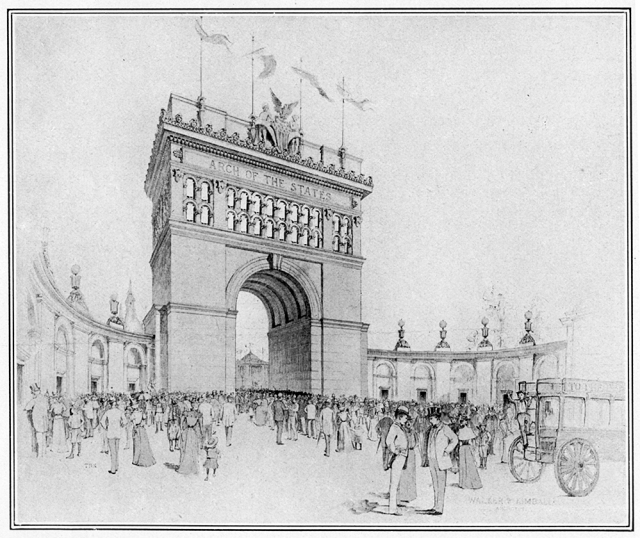

From the very beginning, the Trans Mississippi Exposition board desired a permanent souvenir of their grand accomplishment. A new park would be created from a portion of the exposition grounds donated by Herman Kountze, and the exposition board was already looking ahead to memorialize the event on the future park’s grounds. Conveniently, any expenses for permanent improvements to the park grounds could be paid for by the city of Omaha’s parks budget. The board dreamed up a grand monument called the Arch of States, which would adorn the North 20th Street (aka Florence Boulevard) entrance to the Exposition grounds, to forever memorialize their achievements.

The Arch, the Lagoon and the Bridges

The arch was first designed to be made of the finest stone supplied by the quarries of each of the Trans-Mississippi states participating in the exposition. A cornerstone for the arch was laid on Arbor Day, April 22 1897 amid much fanfare in front of thousands of citizens.

As planning continued over the next few months, the board determined that the arch should be made of buff Bedford stone rather than stone from various states, to avoid a “gingerbread” appearance. They also proposed that the central lagoon should become a permanent feature of the future park, spanned by two graceful bridges of ornamental iron.

Scrapping the Arch

The park commission (which agreed to pay for exposition expenses considered as permanent improvements) were shocked at the estimated price tag – the lowest bids were $17,886 for the arch and $15,876 for the bridges, for a total of $33,762 (approximately $920,911.45 in today’s dollars!). The park commission pushed back on the grounds that it would take such a large portion of their budget as to make it impossible to maintain existing parks the following year. The exposition board revisited their original idea to have participating states supply the materials, but by the time that decision was made they determined there was not enough time for the stones to be quarried and transported to complete construction of the arch. The board abandoned their plans for a permanent Arch of States, determining it would be made of the same temporary materials as the rest of the buildings, and instead moved forward with designs for the lagoon bridges.

On January 13th, 1898, notice was published for “Proposals for Bridges” in the Morning World Herald. The proposal requested was for:

“Two highway bridges on Twentieth street in Kountze park, detailed plans and strain sheets to accompany each bid. Design to be artistic. Clear span 40 feet each, 36-foot driveway, with 7-foot sidewalks on each side.”

January 13th, 1898 Morning World Herald

The contract was awarded to the Canton Bridge company for $9,350.

A “Beautiful White City”

The Trans Mississippi Exposition opened on May 30th, 1898. Over the next five months, locals and travelers alike marveled at the scale and beauty of the Grand Court, were dazzled by the White City lit like a fairy-land by incandescent lights (incandescent lighting was a relatively new innovation and no one had ever seen this lighting used on such a marvelous scale). Thousands of visitors no doubt paused on the bridges to contemplate the reflected beauty of the pristine fabricated city in the water, and forgetting the economic hardships experienced for much of the 1890s, and looked towards the future with optimism.

Plans for the Park

After the close of the exposition, the park commission and expo board commenced discussion of restoring the grounds for Kountze Park. The park commission was generally favorable to keeping the bridges as a memorial, but they did not want to retain the lagoon. For one thing, the lagoon was 2,000 feet long and far exceeded the length of the area that would become Kountze Park. Additionally, the lagoon was built with vertical walls so they could fill the water to a uniform depth of five feet. The park commission (obviously not consulted on the lagoon’s design) wanted a shallower lagoon with gently sloping shores to allow visitors to approach the water. Reconfiguring the lagoon would create a new problem — their existing height would be at least four feet higher than what they would want to connect to a driving boulevard. The park commission determined it would be better for exposition management to fill in the lagoon entirely, allowing the park commission to build the lagoon they desired at a later point. They also discussed the idea of removing one of the bridges to North Omaha’s Miller Park to span the creek (which was said to be badly needed), and putting the other bridge to use somewhere else.

The success of the Trans Mississippi Exposition stirred the desire to hold yet another exposition the following year. Responsibility for the exposition grounds transferred from the Trans Mississippi Exposition board to the Greater America Exposition board, placing park plans on hold. The Greater America Exposition opened on July 1 1899 and closed on October 31 1899. The second exposition was poorly executed and lost a lot of money. The Greater America Exposition board hoped to recover their losses by selling the demolition rights.

Wrecking the Expo

Rights to demolition the property were sold to the Chicago Wrecking Company for $50,000. They were optimistic that all could be dismantled within a month and that very little would be left at the end of the year to show that the expositions had been held there. Unfortunately, the demolition did not go swiftly or smoothly. They were delayed from any significant demolition until November 20, 1899, due to various liens and lawsuits filed against the Greater America Exposition by vendors and contractors who were owed money. Work was slow going, and the site was a mess of debris for months. In April 1900, the wrecking company had dismantled the majority of the buildings except the Apiary and Transportation building. A massive fire broke out in the Transportation Building, which could not be put out due to the oil saturated floors (during the first expo the building had housed heavy machinery) and a fierce north wind. The building had housed the most valuable materials the wrecking company had not yet transported, such as windows and timber. It was a complete loss.

After the fire destroyed the Transportation Building, the wrecking company had little left to do but transport the remaining materials stored in railcars, which was completed in May 1900. The one-time Grand Court was now a field of debris – piles of staff from the buildings, a massive hole surrounded by piles and sheeting which once contained the beautiful lagoon. A dispute had arisen as to who was responsible for putting the grounds back in order by removing all the debris and filling in the lagoon. The City of Omaha Park Commission had an agreement prior to the first exposition that the Trans Mississippi board would bear the expense and responsibility for restoring the grounds so the city could turn it into a park.

The Trans Mississippi board claimed that the obligation had transferred to the Greater America exposition prior to the second exposition. However, the Greater America exposition company was bankrupt. The grounds lay in wreckage and nearby residents and property owners were anxious to have the site cleaned up. In July, Herman Kountze declared that he would pay for filling in the lagoon himself. Efforts finally started in September 1900, with the debris and staff littering the grounds used as fill material.

Keeping the Bridges

The park commission had decided to abandon the original plan of keeping the ornamental bridges in Kountze Park. The bridges were too large and highly curved to span any lake the park commission would create on the eleven-acre site. Instead, they decided to have both bridges transported to Miller Park and installed near the north and south entrances.

In the spring of 1901 a contract was let to a contractor Barnum, a house mover, to move the bridges for $474 per bridge. On April 17th, 1901, the Morning World Herald reported that contractor Barnum had “at last succeeded, with the aid of dynamite” in loosening one of the bridges from the concrete foundation. The 200-ton bridge was loaded onto rollers and waiting for the mud on Florence Boulevard to dry. On May 1st, the paper reported that the bridge had been moved only a short distance when the weight broke the contractor’s equipment. A month later contractor Barnum gave up his contract after moving the bridge only halfway to Miller Park, telling the park board he had already lost too much money in the attempt. Eventually the bridge was delivered to Miller Park (I didn’t find any mention of who completed the move) probably by July 1901. Bids were requested on moving the second bridge from the Expo grounds to Miller Park. In July, a contractor attempted to use dynamite to remove concrete from the center of the bridge, but gave up the contract after several failed attempts. At this point, the park board was desperate to get the remaining bridge out of Kountze Park and were willing to give the bridge to Contractor Barnum, providing he removed it by the use of dynamite or any other means. There is no evidence that Barnum took the deal, and in August 1901 the World Herald reported that as the lagoon was (still) being filled in, the bridge stood as “a mark of the impotency of the park commission against its onerous weight”.

By January 1902, both bridges had finally reached Miller Park, though they were not yet in use as one was awaiting the roadway to be finished, and the other bridge had to be restored, as the only way it could be moved was to dig out the concrete from the center of the bridge and throw it away. This work was likely completed that year. Omaha finally had its memorial to the Trans Mississippi Exposition – four years and several thousand dollars later.

Over the years, the city grew and so did demands on its infrastructure. The bridges adorned Miller Park over what appeared to be an idyllic stream, but what became in fact an open sewer. For years, the big North Omaha sewer had emptied into the creek running through Miller Park. In 1912, residents began to complain that the open sewer was a nuisance and demanded a true sewer constructed in the park. At this time, the city was spending a tremendous amount of money updating sewers all over the city, which could not meet the demands of a growing population. The project was added to the budget for 1915, and a 12-foot-wide storm sewer was installed and the creek filled in, just in time for development of the Minne Lusa subdivision, directly north of Miller Park. A clubhouse was built by the Prettiest Mile Club soon after. The north bridge was right next to the clubhouse, and made for a picturesque setting.

As the Minne Lusa division grew, the creek running north of Miller Park was also replaced with sewer and paved as Minne Lusa Boulevard. Without a creek, the bridge was no longer necessary. On March 27, 1918, the Omaha World Herald published a short notice that the steel bridge at the north entrance to Miller Park would be moved to Carter Lake Park, along with a mention that the bridge originally adorned one end of the lagoon at the Trans Mississippi Exposition. This was possibly planned as part of a new resort and residences reported in the Omaha World Herald a year earlier. The new area would have “a 300-foot circular lagoon with the boulevard running around it. The lagoon would be connected with the main lake by graceful concrete bridges and boats and launches will come up under these bridges right up to the boat landings along the waterfront.” I found no evidence that the bridge ever made it to Carter Lake Park. I examined numerous photographs of Miller Park and scoured newspaper articles and city reports and couldn’t find any trace of the bridges after 1918. Twenty years after the glorious Exposition these bridges were meant to permanently memorialize, they appear to have vanished without public comment.

Burying the Bridge

“The Bridge Wasn’t Needed Anymore, So We Buried It.”

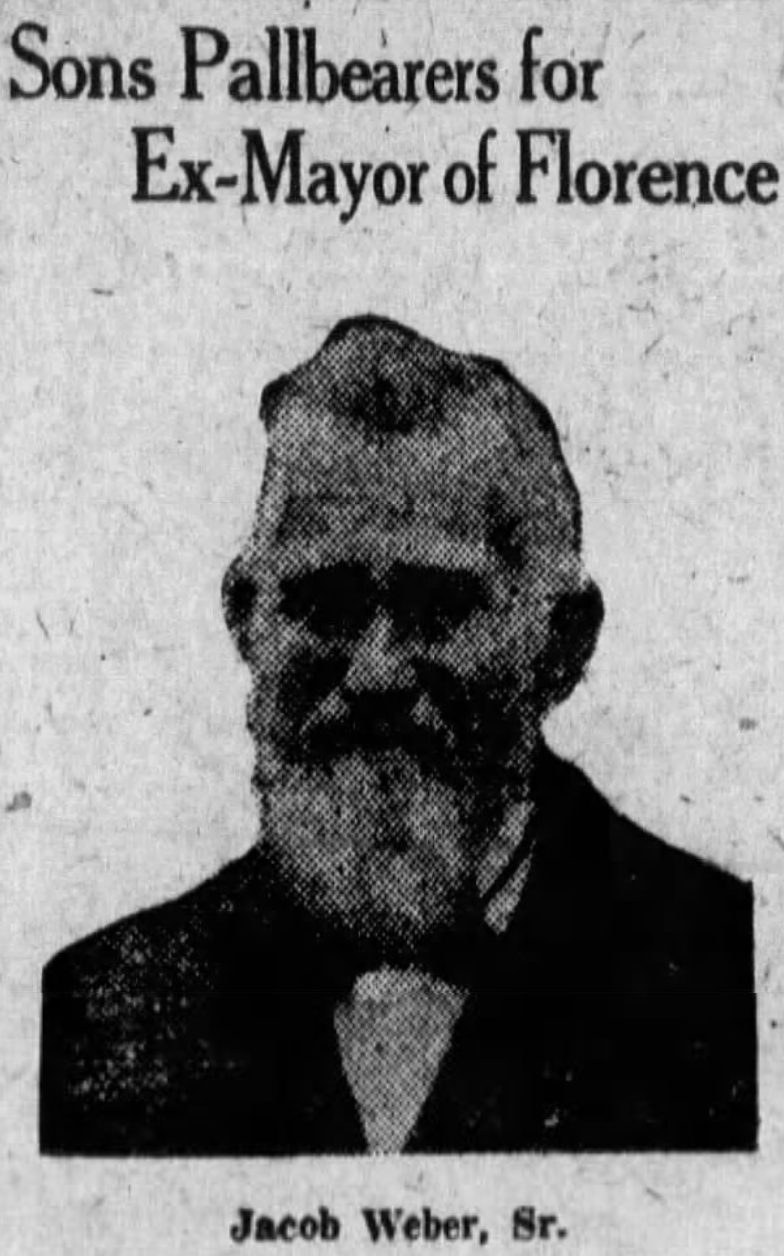

-City of Omaha Parks Commissioner J.B. Hummel

In 1933, utility workers digging in Miller Park discovered one of the missing bridges. Halfway through the park, they found a buried bridge. Using acetylene torches, they cut through 36-inch steel girders and broke up the cement with air compressors so they could lay water and gas lines. Longtime Omaha Parks Commissioner J.B. Hummel told the World Herald “The bridge use to cross a gulley in the park. We laid a sewer there, and filled the gulley in. The bridge wasn’t needed any more, so we buried it.”

This same bridge resurfaced in 1942, during a scrap drive to help the war effort. Sponsored by the Omaha World Herald, readers were encouraged seek out scrap metal at home and work, and collect it for Uncle Sam. Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts would canvass neighborhoods asking residents if they had anything to give.

Inspired by patriotic spirit, readers offered not only rusty junk, but valuable items as well. Veterans donated “souvenirs” they kept from previous wars, such as helmets, guns, bayonets and swords. Fort Omaha donated two old brass cannons and civil war mortars that had decorated the grounds. The Omaha World Herald removed the bronze torches that adorned their building, and Bosco, a 1927 statue of a baseball player in Elmwood Park placed by the Omaha Amateur Baseball Association, was “drafted” for the war effort and added to the pile.

On July 22, 1942 the Omaha World Herald printed a letter they received suggested the city dig up “the old steel arch bridge in Miller park”. It stated that the bridge originally came from the Trans Mississippi exposition and was placed at what is now Minne Lusa Boulevard and Redick Avenue. When the bridge was no longer needed, the bridge was buried because of the high cost to move the bridge.

A few days later, the parks department located the buried bridge in Miller Park – not at the north entrance near Minne Lusa Boulevard and Redick Avenue, but near the south end of the park. The Omaha World Herald reported that the bridge was indeed one of two bridges that spanned the lagoon at the Trans Mississippi exposition. One of the bridges was placed at the north entrance of the park, and when it was no longer needed, it was “broken up, carted away”. The other bridge was dropped into the creek and buried.

The park department uncovered the edges of the bridge and offered to donate the estimated seven tons of steel to the scrap drive, but there was a problem; the bridge was buried underneath a road in the park, and a lack of manpower and technical knowledge prevented the park from removing the 20-foot wide, 60-foot long bridge themselves.

The Mystery of the Lost Bridges

After this point, the trail grows cold, at least in the Omaha World Herald and Daily Bee. To continue the search, I put together the following timeline:

- 1901 (August) – First bridge moved to Miller Park and placed at the north entrance but is not yet in use. Second bridge is moved and placed towards the south of the park by the end of 1901.

- 1902 to 1914 – both bridges adorn Miller Park for at least twelve years.

- 1915 – Sewer installed in through Miller Park, replacing the creek. South bridge is dumped in the creek and buried.

- 1918 (March) – North bridge is still in park through this date, when it is reported that the bridge will be moved to Carter Lake Park. Bridge is not moved to Carter Lake Park and it disappears without any mention in the newspaper.

- 1933 – South bridge is found while digging trenches for utilities. Workers do not excavate the bridge, but cut through it. Bridge is reburied.

- 1942 – Ends of south bridge are uncovered after newspaper reader suggests that it be removed for the scrap drive. The Omaha World Herald confirms that the bridge is one of two that originated from the Trans Mississippi Exposition. The other (north) bridge was “broken up, carted away”. Parks department cannot remove the bridge themselves and offers it to anyone who is able to remove it.

Did anyone ever rise to the occasion and dig up the bridge for scrap? Unable to find a follow-up story, I imagined something that would be too good to be true: What if no one was able to heave the massive bridge from the ground and it was buried again. What a tantalizing thought! I allowed myself to daydream that the bridge was still buried and waiting to be found. I daydreamed that the Nebraska State Historical society would arrange for excavation based on my research and unearth the only remaining structure from the Trans Mississippi Exposition, and it would be removed and exhibited in the Durham Museum for all to enjoy.

Searching for Buried Treasure

Using a photo from one of the newspaper articles, I was able to locate where the bridge might be buried. Knowing the bridge would be on the south end of the park, it was probably south of the current pond. The bridge was under a road, and in the background of the photo two homes were visible. Assuming the photo was taken facing south towards Kansas Avenue, I compared these two homes with images on Google StreetView and found they most closely matched 2721 and 2723 Kansas Ave.

The bridge was buried directly north of these two homes, underneath Miller Park Drive! A satellite image on dogis.org (Douglas-Omaha Geographic Information Systems) with sewer overlays showed that the suspect location was directly east of the existing sewer.

Not only did I want to determine if the south bridge was still buried in the park, the lack of records for the north bridge was bugging me. Why wasn’t the bridge moved to Carter Lake Park? Was it truly “broken up” and “carted away”, as the 1942 World Herald article stated, or was it possibly moved somewhere else?

I had to take my search offline and into the library. I looked through Annual Reports for the City of Omaha for years 1914 through 1919 looking for any clues or comments regarding movement or maintenance of bridges in Miller Park and came up empty handed. One of the librarians on duty recommended I contact Martha Grenzeback, a librarian with a passion for history. I sent Martha an outline of my research and asked if she knew of any resources that might help me solve the mystery. Martha promised she’d check her archive room which had uncatalogued materials not available to the general public. She found some great sources, such as scrapbooks from Parks and Rec and Joseph Hummel himself, and MUD jobsite photos, but nothing that answered any of my questions.

Next, I tried emailing Metropolitan Utilities District and Omaha Public Works to share my research and see if they had anything to contribute. Omaha Public Works replied to suggest I call the Parks Department, but the response from MUD was much more helpful.

My inquiry was passed along to Jeff Schovanec, Director of Engineering Design. He emailed me, stating that their older records didn’t allow for an effective search by date, but they could try to search by geographic area. His cursory guess was that the bridge was still in the park, buried beneath a gas or water main. He wasn’t optimistic about finding any records, stating that when unusual situations are encountered during construction, they often aren’t documented because of the time and energy to do so outweighs the value.

After a few days, I received another email from Jeff. They could not find any records to confirm the 1933 newspaper story, and there were no gas or water mains that appeared to be located in the theoretical burial location. However, there were two sewers that intersected the possible bridge location.

Jeff felt that Omaha Public Works might be able to provide more information, since it was sewer work that prompted the burial of the bridge in the first place. He referred me to “sewer expert and history buff” Jim Theiler P.E. of the City of Omaha Public Works.

I sent my research to Jim and asked if he could shed any light on the mystery. He graciously copied my email to one of their Engineers in Public Works, and two of their Parks Planners. Engineer Eitan Tsabari believed that an unexpected structure was found while digging in the area during sewer separation work, and he copied Robert Norris, Vice President and C.O.O. of Roloff Construction, whose firm was contracted for those projects.

Finally, Mr. Norris replied and solved the case: In the summer of 2008 during the 30th and Laurel Sewer Separation Project, Roloff construction forces encountered a bridge in the park! Unfortunately, the bridge was completely dug around, drug out of the hole, cut up and hauled away for scrap. A follow-up email from Dennis Bryers, Park & Recreation Planner confirmed that the remains of a bridge were found in the area marked on my map.

This confirms that the south bridge was buried in Miller Park (most likely during the 1915 sewer installation), discovered during construction work in 1933 and reburied, uncovered and offered for scrap in 1942, reburied again and forgotten for another 66 years, only to be found for the last time, dug up and scrapped in 2008 during sewer work.

I expected that the bridge had been removed, either in 1942 for the scrap drive, or at some other point when utility and sewer work was done. But I did not expect it to have happened so recently, within my adult lifetime. Ouch.

Without any records relating to the north bridge, the mystery remains open, though I expect it was scrapped long ago. Perhaps someone else will pick up the search?

Throwing Away Monuments

Omaha disposed of not one, but two monuments designed to commemorate the glorious exposition of 1898. Perhaps the failure of the 1899 exposition, coupled with the two-year ordeal and expense of relocating the bridges and cleaning up the exposition grounds, eventually reduced the bridges from historical monuments to obstacles in the way of progress. The south bridge was unceremoniously buried in 1915 under the leadership of park commissioner Hummel when it became functionally obsolete. The decision was probably made as a matter of practicality, given the bridge’s tremendous weight and the fact that a duplicate bridge remained at the north entrance of the park. When the north bridge met its (probable) demise, the city at least considered moving the bridge to Levi Carter Park. Why those plans were never carried out may remain a mystery, but I can speculate that the cost was determined to be too prohibitive at the time.

The lagoon bridges were designed and constructed to forever commemorate not just the Trans Mississippi Exposition of 1898, but the spirit of Omaha that dreamed of such a grand endeavor. Unfortunately, no one dreamed that these monuments would ever need to be moved.

Michele Wyman is an amateur genealogist focused mainly on her Sicilian ancestors who settled in Omaha beginning in the late 1890s. As a member of Forgotten Omaha and administrator of Omaha History Club on Facebook, she has enjoyed discussing, sharing, and digging deeper into the past. Michele believes that learning about the history of her hometown, its neighborhoods, and its people provides valuable insight into the motivations and attitudes that continue to influence Omaha today.

You Might Like…

MY ARTICLES ABOUT THE TRANS-MISSISSIPPI AND INTERNATIONAL EXPOSITION

GENERAL: Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition | Greater America Exposition | Locating the Expo | Demolishing the Expo

BUILDINGS: Administration Arch | Machinery and Electricity Building | Manufactures Building | Girls and Boys Building | Old Plantation | Sod House | Mines and Mining Building

EVENTS: Congress of White and Colored Americans

RELATED: Lost Monument | Omaha Driving Park | Kountze Park | Kountze Place

Sources

- “How Park Board Will Help. Share it Will Take in Fitting up the Grounds of the Exposition.” Omaha World Herald 11 Jul. 1897: 5. NewsBank. Web. 3 May 2016.

- “Bridges on the Lagoon.” Omaha World Herald 24 Nov. 1897: 5. NewsBank. Web. 27 Jun. 2016.

- “Arch of States Permanent Will be Memorial of Exposition at Entrance to Kountze Park.” Omaha World Herald 28 Nov. 1897: 12. NewsBank. Web. 3 May 2016.

- “Bridges over the Lagoon No Resolution to Remove Them by Park Board.” Omaha World Herald 30 Oct. 1898: 3. NewsBank. Web. 22 Jul. 2016.

- “Bids Astound the Board. Arch of the States and Lagoon Bridge Too Expensive at First Figures.” Omaha World Herald 14 Dec. 1897: 8. NewsBank. Web. 3 May 2016.

- “Some Change in Plans. Alterations to be Made in the Arch of the States.” Omaha World Herald 16 Dec. 1897: [1]. NewsBank. Web. 3 May 2016.

- “Proposals For Bridges.” Omaha World Herald 13 Jan. 1898: 6. NewsBank. Web. 3 May 2016.

- “Bridge Contract Awarded.” Omaha World Herald 23 Jan. 1898: 10. NewsBank. Web. 19 May 2016.

- “Bridges over the Lagoon No Resolution to Remove Them by Park Board.” Omaha World Herald 30 Oct. 1898: 3. NewsBank. Web. 22 Jul. 2016.

- “Reshaping Lagoon for City President bates Tells of Park Board Views on the Kountze Site.” Omaha World Herald 11 Nov. 1898: 8. NewsBank. Web. 27 Jun. 2016.

- “Exposition City is Sold White Buildings and Property Bought from Trans-Mississippi Bring $50,000. Chicago Company.” Omaha World Herald 8 Sep. 1899: 3. NewsBank. Web. 18 Jul. 2016.

- “Will Soon be a Wreck. Handsome Buildings at Exposition to be Quickly Dismantled.” Omaha World Herald 23 Oct. 1899: 5. NewsBank. Web. 18 Jul. 2016.

- “Financial View of it. Greater America in Debt About $130,000.” Omaha World Herald 2 Nov. 1899: 8. NewsBank. Web. 18 Jul. 2016.

- “Enjoins “Wrecking” Buildings. Cady Heads off Demolition of White City until Claim is Paid.” Omaha World Herald 2 Nov. 1899: 2. NewsBank. Web. 18 Jul. 2016.

- “An Army of Demolition. it Occupies the White City and Wrecking Begins next Week.” Omaha World Herald 4 Nov. 1899: Page 9. NewsBank. Web. 18 Jul. 2016.

- “Will Tear down next Week Demolition of Exposition Buildings Will Then Not be Tied Up.” Omaha World Herald 10 Nov. 1899: 8. NewsBank. Web. 18 Jul. 2016

- “May be Omaha’s Pet Park.” Omaha World Herald 10 Nov. 1899, LAST: 9. NewsBank. Web. 27 Jun. 2016.

- “Wreck of the Exposition. Scenes of Once Transcendent Beauty Now One of Desolation.” Omaha World Herald 12 Mar. 1900: 4. NewsBank. Web. 20 May 2016.

- “Would Have Torn It Down Today.” Omaha World Herald 11 Apr. 1900, LAST: 1. NewsBank. Web. 19 May 2016.

- “Wrecking Company is Unlucky Paid off Liens on the Exposition Building Day before the Fire.” Omaha World Herald 12 Apr. 1900: 3. NewsBank. Web. 19 May 2016.

- “Fire Shortens Wreckers Stay They Expect to Abandon Exposition Grounds in About Thirty Days.” Omaha World Herald 13 Apr. 1900: 7. NewsBank. Web. 19 May 2016.

- “Park Board Reorganized. Evans President, Lininger Vice and Mary Peake Elected as Secretary.” Omaha World Herald 23 May 1900: 2. NewsBank. Web. 20 May 2016.

- “He Will Fill The Lagoon. Herman Kountze Does Not Wait For the Exposition Association to Put Earth Back in the Lake.” Omaha World Herald 26 Jul. 1900, LAST: 1. NewsBank. Web. 20 May 2016.

- “Park Board Affairs.” Omaha World Herald 31 Aug. 1900, LAST: 3. NewsBank. Web. 23 May 2016.

- “Park Commission Plans.” Omaha World Herald 7 Mar. 1901, LAST: 8. NewsBank. Web. 23 May 2016.

- “Removal of Park Bridges.” Omaha Daily Bee 26 Mar. 1901, Pg.9. Nebraska Newspapers. Web. 23 May 2016.

- “Lagoon Bridges on Wheels. Will be Moved When Mud Dries-Park Improving.” Omaha World Herald 17 Apr. 1901: 8. NewsBank. Web. 20 May 2016.

- “Lagoon Bridge Moves Slowly.” Omaha World Herald 1 May 1901: 7. NewsBank. Web. 27 Jun. 2016.

- “Park Commissioners. Meet for First Time in Many Months and Talk of Work.” Omaha World Herald 30 May 1901: 2. NewsBank. Web. 23 May 2016.

- “Session of Park Board.” Omaha Daily Bee 26 Jun. 1901, pg. 5. Nebraska Newspapers. Web. 23 May 2016.

- “To Restore Kountze Park. Contract for Filling Lagoon is Let to W. J. Yancy.” Omaha World Herald 12 Jul. 1901, LAST: 4. NewsBank. Web. 27 Jun. 2016.

- “It is an Elephant Still. Bridge Across Lagoon in Kountze Park Causes Considerable Worry.” Omaha Daily Bee 17 Jul. 1901, pg.7. Nebraska Newspapers. Web. 23 May 2016.

- “Debris of the Exposition. Last Trace Are Seen on Site of Lagoon Bridges.” Omaha World Herald 8 Aug. 1901: 4. NewsBank. Web. 23 May 2016.

- “Miller Park Bridge.” Omaha World Herald 20 Aug. 1902, LAST: 2. NewsBank. Web. 23 May 2016.

- “Move Bridge to Carter Park”. Omaha World Herald, 27 Mar. 1918, p. 14. NewsBank. Web. 27 Jun. 2016.

- “Burn Buried Bridge Found in Miller Park.” Omaha World Herald, 17 Nov. 1933, HOME, p. 8. NewsBank. Web. 23 May 2017.

- “Bridge Offered for Scrap; It’s Buried Under Road.” Omaha World Herald 24 Jul. 1942, Home: 6. NewsBank. Web. 27 Jun. 2016.

- “Cannons to Boom Again; Give Bridge.” Omaha World Herald 25 Jul. 1942, Sunrise: 7. NewsBank. Web. 27 Jul. 2016.

- “Sewer Excavation Turns Up Pieces of Omaha’s Glorious Past.” Omaha World Herald, 24 May 1980, Sun Up, p. 1. NewsBank. Web. 24 May 2017.

- “Find in Trench Dusts Off Exposition Questions.” Omaha World Herald, 11 Jun. 1980, Sunrise, p. 4. NewsBank. Web. 24 May 2017.

Leave a comment