OMAHANS HAVE BEEN MISINFORMED!

We like history. We want to be proud of the past. Sometimes, in order to be proud, we intentionally forget, ignore, or otherwise let go of the parts of the past that we’re not proud of.

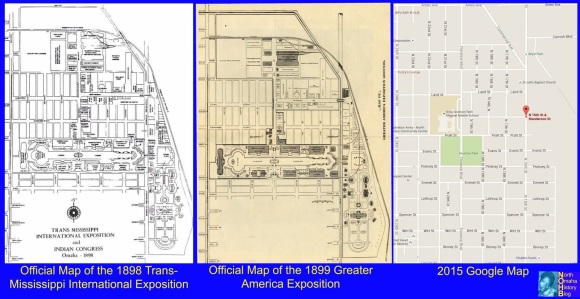

For years, the people of Omaha have been told that all of the buildings of the 1898 Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition were demolished right after the event ended in the fall of that year. But they weren’t destroyed!

Instead, after all the success Omaha had with the Expo, a group of investors decided they needed to keep the buildings up and start another grand event. Working together, they raised enough money to buy the buildings.

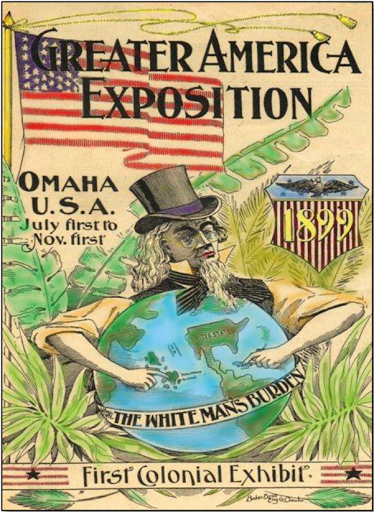

In 1899, this group created a second event, swearing to Omaha’s residents it would be bigger than the first. They called it the Greater America Exposition. Unfortunately, they’d planned a racist, opportunist crapshoot designed to soak up money from visitors. Because of this, and simple bad planning, the second Omaha Expo is generally thought of as a failure today.

The End of the Trans-Mississippi Expo

After the Trans-Mississippi Expo ended in 1898, a group of investors immediately collected money from 200 people in order to buy the Expo grounds in Kountze Place.

Some buildings were torn down right away. Of the fifty state buildings at the Expo, the Kansas and New York buildings went first, with the New York building getting converted into a duplex somewhere in the neighborhood. The Nebraska building was moved and converted into storehouse for state property. The Minnesota, Iowa and Wisconsin buildings went shortly after.

However, with rumors of another event the following year, many states decided to keep their buildings standing. The City of Omaha’s Parks Board waited on pulling out the trees, shrubs and flowers lent to the Expo, too, as they wanted to see what would happen.

Edward Rosewater, publisher of the Omaha Bee, chaired a committee dedicated to launching a new Expo in 1899. On November 1, 1898, this committee bought every part of the Trans-Mississippi Exposition, including,

“…buildings, appurtenances, engines, apparatus, materials and furniture for the sum of $17,500.00 and the assumption by the purchasers of all the obligations to the owners of lands leased for the purposes of the Exposition.”

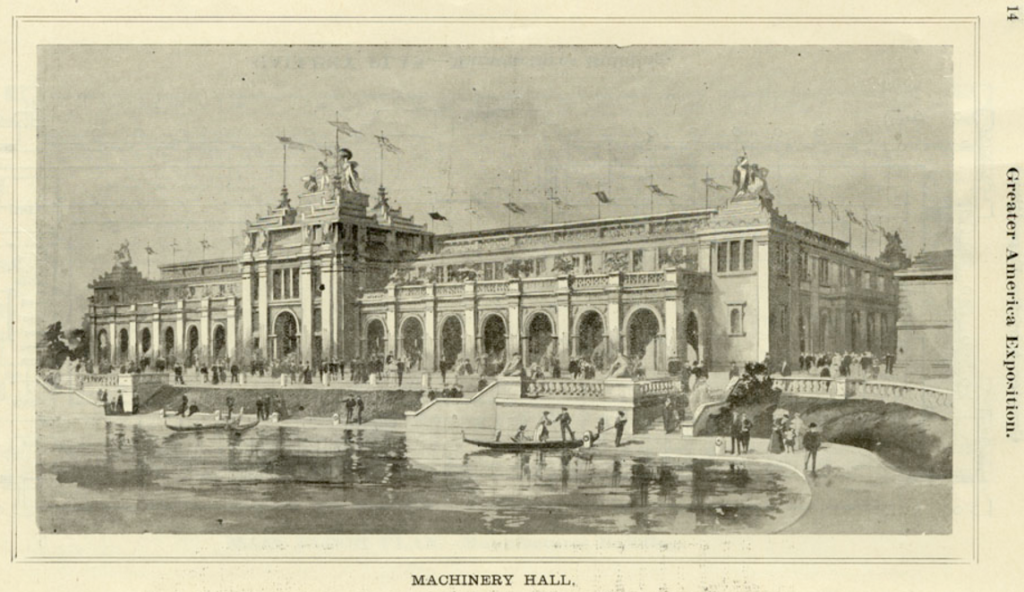

If scenes from the Greater America Exposition look identical to ones from the Trans-Mississippi Exposition look similar, that’s because in many places they were!

Spanish-American War Ends

In August 1898, the Spanish-American war ended, and in late November, Spain accepted the American terms for peace. In December, President McKinley said he favored Omaha hosting another expo during 1899 for the nation to share its new “possessions” gained from the war. That included Cuba, Guam, Philippines, and Puerto Rico.

At that time, racism was flaring across the United States. Staking out its colonial power through the Spanish-American War, the U.S. suddenly began to flex muscles it had only used within its boundaries before that. Now they wanted to show off the treasure trove of culture they stole from their new territories.

By late December 1898, the Expo’s lagoon was opened to ice skaters for season. That same month, the new gathering gained a name, now being called the Greater America Exposition of 1899. By Christmas, it was decided that the 1899 Expo will reflect the United States on a miniature scale. In March, Dr. George L. Miller was elected the chairman of the Greater America Exposition executive committee. That same month, the Omaha Bee used several posters by renowned artist John Ross Key to promote the Expo in the newspaper.

Rides and Exhibits

By March 1899, the federal government agreed to bring exhibits from all its new colonies. This event was definitely intended to be a celebration of American colonialism, the American empire, and the spread of military-driven capitalism. Many of the presentations were plainly racist, actively and deliberating attempting to show that white people were superior to every other person around the world.

Since plans for the GAE were picking up in March, people were getting big visions of what could be. However, by April 7, 1899, 20 concessions had been closed. The GAE managers were worried people already had enough of some Midway rides during the TME.

In April, a new exhibit was added. Made of the collection from the Libby War Prison Museum from Chicago, it was a private collection created by Charles Gunther. After closing his building early in 1899, the collection came to Omaha for the Greater America Exposition of 1899 before going back to Chicago. It was moved into the Government Building.

Also by the end of April, agreements were made for…

- The Nebraska Building to be used for a women’s display, as well as offices for the state fair and the fraternal organizations;

- The Illinois building to be used by the fraternal organizations;

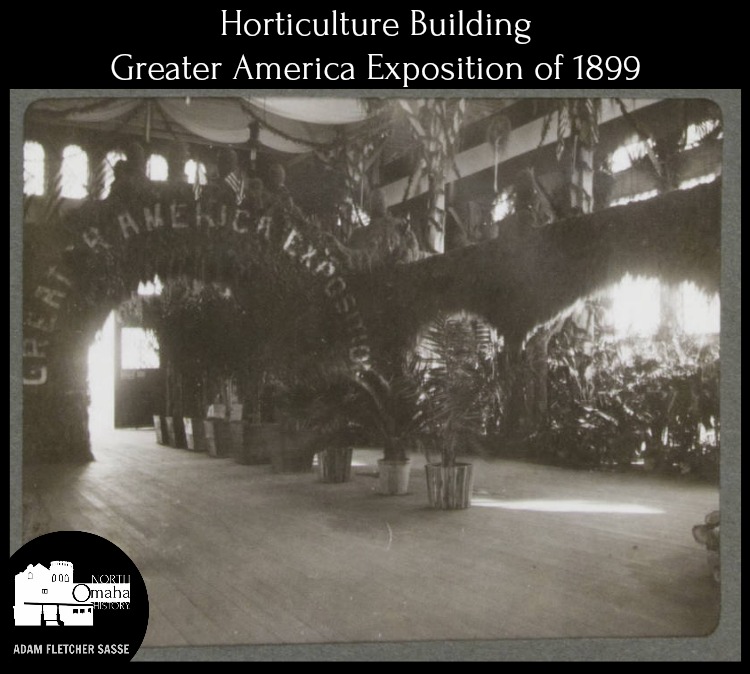

- The Agriculture and Horticulture Buildings to be used by the Nebraska State Fair exhibits;

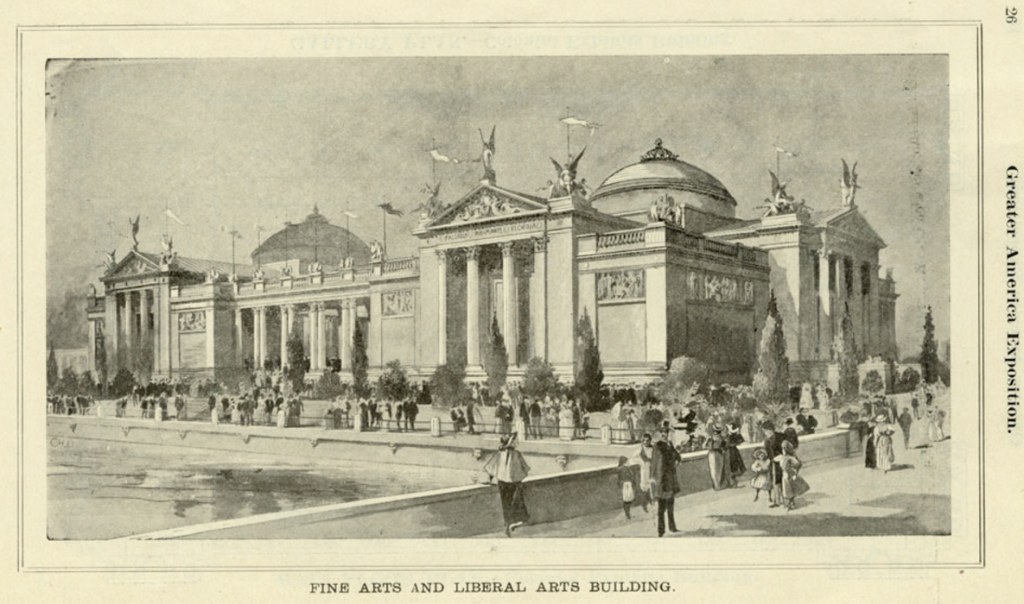

- The Liberal Arts Building to be filled with the new American Colonies display.

That month, as many as 500 men were working on the grounds. They painted and patched building, and cleaned and replanted flower beds.

On Sunday, May 8, 1899, the expo grounds were officially re-opened for the first time. At the same time, architectural repairs were started in main court. The Omaha Electric Light Company was contracted to furnish power for live exhibits, the Midway, and lights on grounds, and more than 40,000 new lights were added throughout the expo grounds. The public was welcome into the grounds officially on May 31, 1899.

In early June, 1899, Omaha’s merry-go-round that was at 15th and Capitol Avenue in downtown for almost a decade was moved to the expo grounds near the giant see-saw.

That same month, arrangements were finalized for the Government Building to feature the Libby War Prison Museum and a North Pole collection. The Horticulture Building was filled with palms, tropical plants and fountains, along with 100 cages of singing birds, canaries and parrots. The Temple of Palmistry became home of the Omaha Occult Society, and the Orpheus Vaudeville Theater occupied the former site of Chinese Village.

Attractions and Performances

Some of the rides and displays at the Greater America Expo included:

- The Enchanted Island, aka “At Midnight in Hawaii”

- An electric scenic theater

- The Cyclorama “Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge”

- Old Plantation

- Electric Wargraph Theater with Hobson sinking the Merrimac

- The Giant Seesaw

- A Chinese village

- A Cairo Street

- Spanish War Museum

- Hawaiian Village

- Living Wounded Heroes exhibition

- “Fat Man’s Beer Garden”

- Moorish Palace

- Arizona cactus garden

- Deep Sea Diving exhibition

- Mexican Village

- Philippine Village

- German Village

- Porto Rico [sic] and Cuban Village

- Electric fountain display

- Royal English Marionettes

- Phantom Swing

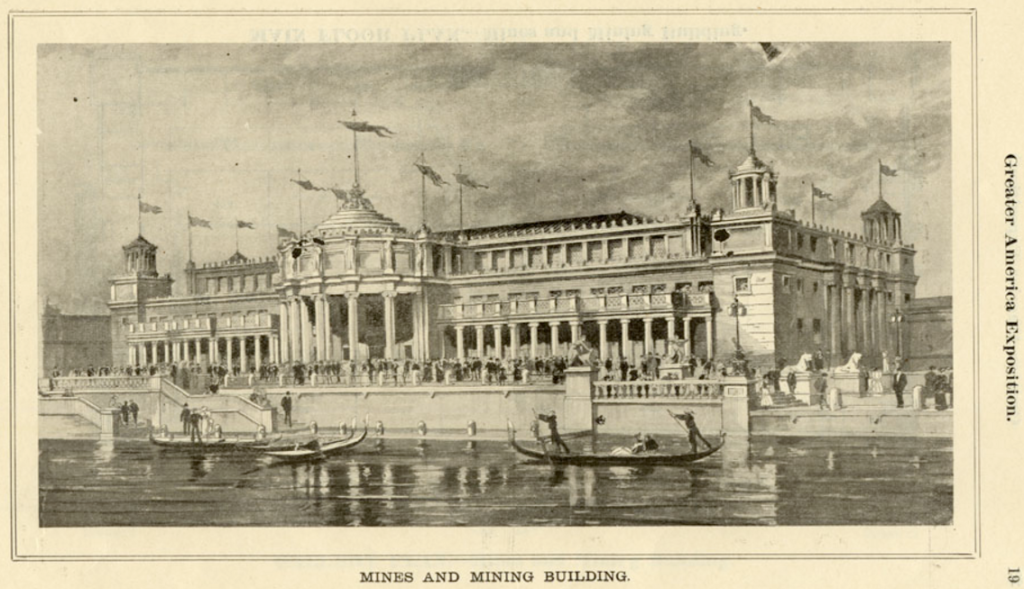

- Gondolas

- Lunette

- Hagenbeck’s Wild Animal Circus

- Naiads of the Fountain

- Milwaukee Dairy

- Venetian gondola rides Red Windmill of Paris

- Chutes

- The Creche or Omaha Day Nursery

- Royal Japanese troupe of super acrobats

- Beckwith Aquarium, and

- The Enchanted Chamber.

In April 1899, the organizing committee for this new expo thought everything was going well, and that huge crowds were likely to show up. However, after fighting with the committee over the previous five months, Edward Rosewater refused to rejoin the committee. He very plainly said they hadn’t raised enough money to make the new expo work. Although he ended up joining, what he said was a sign of things to come…

Finishing Preparations

The committee proceeded making arrangements. The State of Nebraska agreed to canceling the Nebraska State Fair in 1899, and focusing all of its energy on the Greater America Expo. All the walkways were bricked in, 800 trees were planted around the lagoon, and 40,000 electric lights were ordered for the entire Expo. The committee was excited to report that, “GAE is almost a fairyland with 1500 new globes of white fire…”

The Midway was filled by June 1899.

St. Johns Lutheran Church of Council Bluffs purchased the giant “Wigwam” (a 50 foot tall plaster tipi) and planned to run a restaurant in it.

It Wasn’t So Great, and Didn’t Represent America

On July 1, 1899, the Greater America Exposition opened to the public. 28,000 visitors attended on July 4th, reputedly eclipsing the crowd that attended the previous year’s Trans-Mississippi Exposition. All total, in the first week of the 1899 Expo, there were 70,000 admissions, which organizers claimed was far greater than the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Expo.

By the middle of the month, the daily attendance at the Expo averaged 2,000, where the Tran-Mississippi averaged 2,300. On July 20 there was a special event at the Expo for kids, with more than 10,000 children attending. The admission was set at .50c and .25c during day, .25c and .15c evenings and Sundays.

Hard Times Hit the Expo

On July 12, 1899, formal reports of the 1899 Expo revealed that the event is out of money. Edward Rosewater, Jonas Brandeis, Herman Cohn and Thomas Fry resign from the executive committee that day. Rosewater, who had been arguing with the organizers of the Expo since the they started, kept agitating for the next six months.

Two days later, two managers of the event were fired. A new manager borrowed $25,000 to keep the event operating and a new executive committee was formed. The same week, the Denver Times reported that of the Greater American Exposition had no government exhibits, no exhibits from neighboring states, no mining exhibit, no agriculture exhibit, and nothing else of substance. Instead, they declared “it is An Omaha Scheme, simply a big carnival midway.”

At the beginning of August, the executive committee was cut down in size, while superintendents, staff, and security guards were laid off. There were a lot of complaints about wheels, horseless carriages and dogs running loose on Expo grounds that didn’t happen at the 1898 Expo.

That same month, fish started starving in the lagoon. Reportedly, millions of them of all sizes, including minnows, carp, and perch. On August 7, 35 feet of the balustrade (colonnade) on the east side of lagoon fell over onto the sidewalk. Since they were all built to be temporary fixtures, the plaster and horsehair balustrade was going to fall down at some point. On August 14, the bicycle races were cancelled because nobody showed up to watch them. The next night, the fire dance was cancelled after the Expo managers failed to schedule a band to play. Electricity was shut off, the show was declared off, and the audience left in the dark.

On August 18, the Expo’s special “Carnival Night” was cancelled when the lights weren’t scheduled to be left on. Low attendance plagued the Expo for the following month. However, the same week, on Aug. 21, attendance exceeds any previous day, with 12,000 people coming through the gates.

The Picture Gallery room was reportedly only 1/3 full by August 7, looking bare and empty. The water carnival was called off on August 31 because nobody was coming to it. A week later, 26 guards resigned in protest on September 6 after their manager was released.

845,000 people had attended the Greater America Exposition by its closing on October 31, 1899. It was estimated that half of all attendees came on free passes.

Going Out With A Riot?

On October 31st, 1899, approximately 25,000 people came on the last day of the Expo, “swamping the Midway.” At 4pm, all of the electricity in the Expo grounds went off. The workers at the Expo’s coal plant went on strike because they hadn’t been paid. Police raided the building, and the lights were back on by 7pm.

However, “boisterous crowds” took aim at the Expo’s installations once lights went off at 9pm because the Expo was out of coal. As one period reporter wrote,

With the passing of the lights the pandemonium already rampant on the Midway descended into wild commotion. The crowd merged into a wriggling mass of humanity, like an army of centipedes… Signs were torn down, thatching torn off the Filipino Village. When the conglomeration grew more boisterous, the few remaining exhibitors began to close up their doors and box the more breakable goods… Reminding one of the preparations for an expected cyclone.”

Demolition of the Expo

The city government of Omaha and the State of Nebraska frequently voiced concern that there were plans to make the expo grounds permanent, and neither wanted that to happen. Built to be temporary, they wanted to see the wrecking ball swing, and on November 1st, 1899, that happened.

A railroad car packed with demolition equipment arrived on November 4th. Drays, early bulldozers and other machinery torn down buildings buildings immediately. The lagoon was emptied on the first day it was possible. All of the concession stands were closed, and the area businesses were emptied. Court cases were filed against the Expo’s executive committee immediately for unpaid bills, and workers became upset at being short paid by the Expo.

During November, the Giant Seesaw was shipped to Coney Island, where it was used for more than a decade. By November 15th, the original backers of the Expo were paid back.

However, a group of unpaid employees filed a charge against the executive committee, threatening the Expo with bankruptcy. On November 29th, the Expo organization is declared insolvent. J.B. Kitchen, a local businessman who built the first Paxton Hotel in downtown Omaha, offered to head an effort to raise the money owned the workers from other local businessmen. He contributed $1,600 towards the $80,000 owed. Kitchen’s efforts weren’t successful, and on December 30, a judge awarded the workers the money due to them through bankruptcy proceedings.

By January 1900, almost all of the buildings, walkways and other elements of the Expo grounds were completely gone.

There were some closing arguments among the various players involved. At one point, the Greater America Expo organizers threatened to sue the Trans-Mississippi Expo organizers over who was responsible for completing the final touches before the land was ceded to the City of Omaha Parks Board. The Parks Board, which never formally recognized the Greater America Expo organizers, threatened to sue members of the executive committee if the job wasn’t done.

In the final months of cleanup, which were May and June of 1900, there was a fire that took out the last remaining elements of the Expos.

Deaths and Injuries

Several people were hurt at the Greater America Expo, and some died. Here are some of those unfortunate people:

- July 26: Jennie Hoover, 14 year old daughter of the engineer of the Scenic Railroad was wading in the lake and drowned. Midway concessionaires took up a fund to help pay funeral expenses.

- September 4: R. C. Wisner, an employee on the Expo’s Midway, was arrested for reckless shooting. He was firing blanks as part of his show and pointed the gun at some boys, and accidentally shot one of them. The Omaha World-Herald wrote, he was “filling the forehead of one of them with powder, burning the flesh considerably.”

- September 7: Edith Shugart, a 3 year old child, was injured when she was bitten by a dog roaming the grounds. Her father worked at the Expo’s horse races.

- September 10: A Lincoln man put his knee through one of the mirrors in the Mystic Maze and had to be taken to a hospital.

- September 10: Julia Lone Elk, a tribal member participating in a horse race for women, was unconscious after she fell off her horse.

- Sept. 19: A group of seven boys fell from a 70 foot tall tree at N. 21st and Paul Streets while trying to watch the Wild West Show. They were perched on the highest limb of the tree and it broke. One suffered a broken leg.

- Sept. 28: An Oglala Sioux named Conquering Bear who was at the 1899 Indian Congress died in downtown Omaha when he supposedly jumped off a moving street car, fell and struck his head.

Why Not Remember?

I don’t know why more people don’t know about the Greater America Expo. Maybe it has always been eclipsed by the grandiosity and novelty of its predecessor. Maybe the right people weren’t involved. Maybe it really was just a big Midway, filled with fluff and no substance. Maybe it was plain imperialist racism that people don’t want to remember.

Whatever the reason, this blog is an attempt to rekindle the embers, relight the street globes and reinvigorate the streets of North Omaha with the history that built the place. Go ahead, take a ride on the Giant Seesaw and have a grand time!

You Might Like…

MY ARTICLES ABOUT THE TRANS-MISSISSIPPI AND INTERNATIONAL EXPOSITION

GENERAL: Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition | Greater America Exposition | Locating the Expo | Demolishing the Expo

BUILDINGS: Administration Arch | Machinery and Electricity Building | Manufactures Building | Girls and Boys Building | Old Plantation | Sod House | Mines and Mining Building

EVENTS: Congress of White and Colored Americans

RELATED: Lost Monument | Omaha Driving Park | Kountze Park | Kountze Place

MY ARTICLES ABOUT THE HISTORY OF KOUNTZE PLACE

General: Kountze Place | Kountze Park | North 16th Street | North 24th Street | Florence Boulevard | Wirt Street | Emmet Street | Binney Street | 16th and Locust Historic District

Houses: Charles Storz House | Anna Wilson’s Mansion | McCreary Mansion | McLain Mansion | Redick Mansion | John E. Reagan House | George F. Shepard House | Burdick House | 3210 North 21st Street | 1922 Wirt Street | University Apartments

Churches: First UPC/Faith Temple COGIC | St. Paul Lutheran Church | Hartford Memorial UBC/Rising Star Baptist Church | Immanuel Baptist Church | Calvin Memorial Presbyterian Church | Omaha Presbyterian Theological Seminary | Trinity Methodist Episcopal | Mount Vernon Missionary Baptist Church | Greater St. Paul COGIC

Education: Omaha University | Presbyterian Theological Seminary | Lothrop Elementary School | Horace Mann Junior High

Hospitals: Salvation Army Hospital | Swedish Hospital | Kountze Place Hospital

Events: Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition | Greater America Exposition | Riots

Businesses: Hash House | 3006 Building | Grand Theater | 2936 North 24th Street | Corby Theater

Listen to the North Omaha History Podcast show #4 about the history of the Kountze Place neighborhood »

MY ARTICLES ABOUT THE HISTORY OF NORTH 16TH STREET

Places: 16th and Locust Historic District | Charles Street Bicycle Park | State Bar and McKenna Hall | Storz Brewery | Warden Hotel | Grand Theater | Nite Hawkes Cafe | Tidy House Products Company | 2621 N. 16th St. | New Market | 3702 N. 16th St. | Sebastopol Amphitheater

Historic Homes: J.J. Brown Mansion | Poppleton Mansion | Governor Alvin Saunders Estate | Ernie Chambers Court aka Strehlow Terrace | The Sherman Apartments | The Climmie Apartments

Neighborhoods: Near North Side | Lake Street | Kountze Place | Saratoga | Sulphur Springs | Sherman

Events: 1898 Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition | 1899 Greater America Exposition | 1960s North Omaha Riots | “Siege of Sebastopol”

- A History of the Trans-Mississippi Exposition

- A History of Demolishing the Exposition Grounds in North Omaha

- A History of the Kountze Place Neighborhood

Elsewhere Online

- Miller, G. L. (April 16, 1899) “Greater America to the People of Omaha,” Omaha World-Herald.

- UNL Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition website.

- Construction of the Trans-Mississippi Exposition 1897-1898

- “Greater America Exposition at Omaha , July 1 to Nov. l, 1899” by The Bee

- “The Incoherencies of Empire: The “Imperial” Image of the Indian at the Omaha World’s Fairs of 1898-99” by Bonnie M. Miller (2008)

- “Greater America Exposition of 1899” Notes from the planning committee

- “Greater America Exposition Book of Views” (1899)

- “Greater America Exposition: Map of Grounds, Diagram of Buildings” (1899)

Bonus Pics!

Leave a comment