Growing up near 24th and Fort, my imagination was always lit up by what was. As a young paperboy for the Omaha World-Herald, I visited that intersection every day, with Mister L’s being a highlight on my route. Mister L was a OTB bookie who ran a jitney service and all kinds of other, um, services, from his office. He was the one who tipped me well, who sold candy from his office, and who I felt privileged to interact with whenever I got to collect for his paper.

Emerging from the dark green cave that I remember and onto the corner, I remember his building on the southeast corner of the intersection being a distinctly commercial vernacular style, as well as the one directly across from his on the southwest corner. I don’t remember a business being in that building, but there may have been a bar there. On the northeast corner was a laundry, and on the northwest corner was Phil’s Foodway.

Growing up, there were stories of past commercial vibrancy I never actually saw. Corner stores on every corner, North Omaha was a moving, lively place all the way into the 1960s. There were also stories of the riots though. They were ambiguous and shadowy, and nobody explained them very well.

The Long History of Rioting in Omaha

Rioting is an entrenched language in Omaha’s history; they’ve happened a lot in the city’s past. In my research for a Wikipedia article, I found that since the city was founded in 1854, there have been more than 50 major riot events. Labor and management battles, economic toil, European ethnic clashes and criminal enterprises have led to most of the civil unrest in Omaha. So the North Omaha riots weren’t the first or only civil unrest in Omaha history.

Riots had struck North Omaha before the 1960s, too. In the 1910s, two events drew racist Omaha to attack African Americans in the Near Northside. The first was a 1910 bout in Reno, Nevada, where Jack Johnson’s win over a white man sent white racist hordes into the black neighborhood. The devastation was under-reported by each of the city’s papers, but the military was called to the area to quell the rioting.

The other riot affecting the neighborhood was the notorious lynching of Will Brown in 1919. According to era accounts, as many as 10,000 whites gathered at the Douglas County Courthouse. Their attacks virtually destroyed that building, and when they were done they reached beyond the downtown and began marching up North 24th Street. The Army was called in from Fort Omaha to intervene and quell the horde.

However, in the mid-2000s, I researched the riots that ravaged the community where I grew up that people still talked about. I wanted to learn who, what, where, when, and why they happened. After writing a few articles on Wikipedia about them, I want to retell them here as real stories with real people involved. Because they did happen, and when they did, they left scars on North O that still haven’t healed almost 50 years later.

Riots As Consequences, Not Causes

Lots of people in Omaha believe the riots on North 24th Street caused the decimation of the Near North Side. When I was growing up in the 1980s and 1990s, this was a popular narrative among both my African-American and white neighbors. In reality though, the riots were consequences and not the cause of North Omaha’s problems.

Cause: Economic Discrimination

The real issue is that white property owners abandoned North 24th Street in the late 1950s, a decade before the riots happened. There were dozens of empty storefronts along the strip, and fires (arsons) in empty buildings along 24th St. were common between 1954 and 1966. During the same decade, the white Omaha City Council denied funding for recreation activities for North Omaha youth, who became infamously bereft of skating, swimming, movies, bowling and other activities in the Near North Side during the late 50s and early 60s. Finally, the Omaha Public Schools led by self-identified racist Harry Burke allowed schools in the neighborhood to fail, undersupplying teachers, underfunding curriculum and letting buildings fall apart.

These things weren’t happening the same in neighborhoods west of 60th Street, south of Dodge, or north of Ames. Instead, schools were being built and rebuilt and well-funded; the City Council was disproportionately funding recreation opportunities for young people including new parks, pools and other activities; and businesses were opening, re-opening, building and rebuilding in a variety of neighborhoods in ways they did not along North 24th Street.

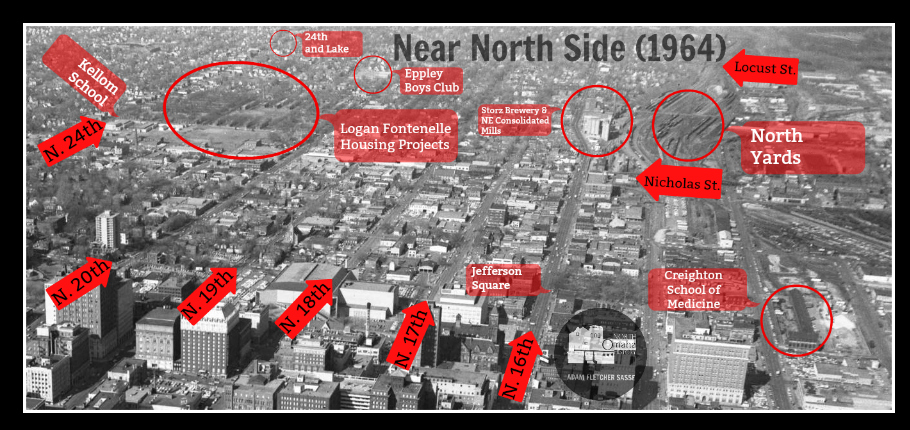

Cause: White Flight

By 1960, white flight was nearly complete from Cuming Street to Locust, North 14th to North 30th. The accompanying divestment in business, civic infrastructure and cultural integration is what led to the riots on North 24th Street between 1966 and 1969. After the events of 1966 to 1969, white flight in the residential and commercial sectors of North Omaha accelerated, first in the Near North Side and Kountze Place neighborhoods, then throughout the entire community, all the way north to Florence and west to North 60th Street, and beyond.

White flight in Omaha has been shown to affect much more than housing and businesses though. My historical research shows that the City of Omaha routinely and strategically divests in regular infrastructure updates when white people move away from a neighborhood, including streets, sewers, parks, sidewalks, streetlights, and more. With few exceptions, in North Omaha, Christian and Jewish congregations which were historically white do not continue in neighborhoods that become largely mixed or predominantly Black. Throughout their history in the community, Omaha Public Schools do not maintain the quality of instruction or access to higher education when they have large populations of African American students.

White flight in North Omaha continues to this day.

Cause: Systematic Racism

The stage was set by the fact of the city’s systematic racism having happened for at least a century of it’s existence. In the 1960s, the government of the City of Omaha was rife with racists practicing racism in policy-making, policing, budgeting, and programs.

Even after the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the City routinely segregated the city’s African-American community. While some legal and social progress was made, there were still a lot of issues. Young people in the federally-owned public housing projects faced abject poverty, substandard education, and an almost complete absence of opportunities for recreation and out-of-school time enrichment.

Cause: Police Brutality

Formerly referred to as “police misconduct,” the reality that police in North Omaha were responsible for beating and murdering Omaha’s African American community for more than a century before the riots. Harassing elderly people, disproportionately targeting Black youth, accosting women and more is part of the trend within the police department that young people were rallying against. In two specific riots, police shootings were directly responsible for youth gathering. Disconnecting from the community, ill-training police officers, under-supporting healthy interventions in the community, and other discrepancies are a marked cause of the 1960s riots.

Symptoms

Each of these conditions, economics and white flight and systematic racism, led to the riots and much of the lesser-scale violence on North 24th Street and in the surrounding community between 1966 and 1969.

After white supremacy enslaved an entire race for 350 years, then segregated that race and beyond for a century afterwards, then wholly divesting from the integrated communities that once served them, Omaha was going to have symptoms reflecting the situation. White flight was the straw that broke the camel’s back of segregation, leading to the riots as an expression of frustration, anger, denial and suffering.

Following are details on each of the major events that happened during that time.

Consequences: Major Riots in North Omaha

Between 1966 and 1969, there were four major riots in North Omaha. Several smaller activities happened too, but the media and politicians chalked them up to vandalism or isolated events. The following major riots had large numbers of participants, deep impact on property, and lasting effects on the community.

Riot 1: July 4, 1966

To most people, a 103 degree July 4th holiday sounds horrible. Add that to all the causes described above, and communities might logically be ready to either melt, or explode. The Near North Omaha neighborhood did exactly that. That day, a crowd of youth gathered at North 24th and Lake Streets. Throughout the day they’d been hanging out. When the Omaha Police Department rolled into the crowd in the evening, police automatically pulled out bats and threatened the people gathered with violence and jail. Within moments, the crowd demolished two police cars. They threw Molotov cocktails into vacant buildings and demolished storefront windows up and down the street. Millions of dollars in damage was caused to businesses, and the riot continued unabated for three days. That day, national representatives from a few different organizations arrived in the city, helping local civil rights organizations come to a resolve with the mayor to fund more programs for the Near North Omaha neighborhood.

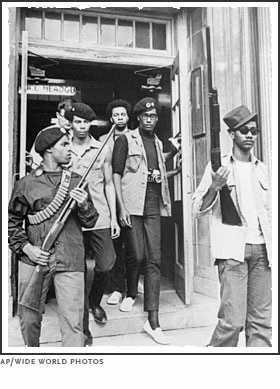

After that, new programs were unveiled throughout the community that ran for many years. The Omaha office of the federal Housing and Urban Development agency (HUD) started funding afterschool programs for youth, and local organizations like the DePorres Club and the local Black Panthers began to fill in gaps.

However, within a month, North 24th Street was on fire again.

Riot 2: August 1, 1966

The riots were lit up again after a 19-year-old was shot by a white, off-duty policeman after a burglary and high speed chase. Eugene Nesbitt was killed the week of July 25th. On Sunday, July 31st he was buried, and the next morning was a riot. Centered at N. 24th and Ohio Streets, several other locations were firebombed as well, with buildings at 3302 N. 16th, 3821 Florence, and 3737 Lake Street torched. Police were dispersed to each of those locations to break up crowds.

The mayor of the city, Al Sorenson, blamed the riots on the black community, while news outlets like the Omaha-World Herald and tv stations fanned the flames by accusing African Americans for the conditions they faced in their neighborhoods. Sorenson also claimed that the riots were orchestrated by the Black Panthers.

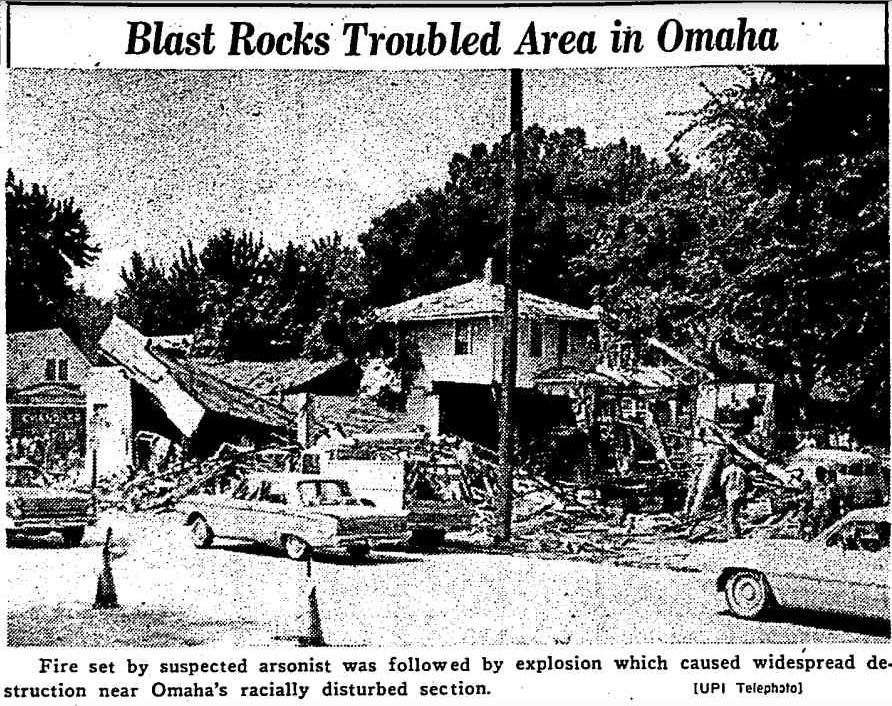

At 2:30am on August 3rd, a firebomb destroyed Harry Brown’s Cafe along North 24th. Five people nearby were wounded, as shrapnel and glass ripped through homes, and several businesses were damaged. Brown’s Cafe was obliterated.

Afterward, 39 businesses reported damage, and dozens more closed or moved away immediately. In three nights of rioting, protesters threw Molotov cocktails and burned and looted more than a dozen businesses. Mayor Sorensen denied calls by protesters to meet with him and Nebraska governor Frank Morrison again, as they had after the July 1966 riots. Morrison said, “there will be no deals with hoodlums again in connection with the racial violence.”

There are few accounts available now, and none of them complete, just 40 years later. However, what is available shows that these riots weren’t intended as black-on-black violence or crime. Groups including the Panthers stood guard outside the offices of the Omaha Star building at 24th and Lake in order to prevent its damage, as well as the historic churches in the neighborhood.

In March 1967, the Midtown Business and Professional Association held a conference at UNO to discuss the 1966 rioting and what to do to stop future riots. “It is better to discuss problems ‘on a cool Thursday afternoon in March than on a hot summer night when the bricks and cocktails are flying.’” At the event, the Nebraska State director of anti-poverty programs, Samuel J. Cornelius, said that the rioting had cost $500,000 in damage. He also said an additional $128,000 was spent stopping the violence and starting “remedial programs” afterwards. He was quoted as saying, “It is easy for our youth to conclude that the community will listen to you if you tear up a half-million dollars worth of property.” He talked about the “sheer accident” that nobody got killed in the riots, that youth would sit down and discuss the problems that led to the riots, and that “we were able to keep the older adults from joining in.” He also said that “riot leaders had set up gasoline storage dumps near Kellom School and in Kountze Park…” and that it was a “sheer accident” that “the dumps were not used.” “And it was by sheer accident that the disturbance was, by and large, confined to the Near North Side.” After that conference, the World-Herald announced that police had “drafted a secret emergency plan for crushing riots” in the future.

The riots were abated for the next year, then came raging back.

Riot 3: March 4, 1968

Two years later, a crowd of high school and university students were gathered at the Omaha Civic Auditorium to protest the presidential campaign of George Wallace, the segregationist governor of Alabama. After counter-protesters began acting violently toward the youths, police brutality led to the injury of dozens of protesters.

During the same time period, on March 5th, an African-American youth was shot and killed by a police officer. Howard L. Stevenson was going through the Crosstown Loan Pawn Shop on North 24th when police caught him. Apparently he refused to cooperate, and police shot him. The next day, riots caused a lot of damage and protesters supposedly caused thousands of dollars of damage to businesses and cars. The following day a local barber named Ernie Chambers helped calm a disturbance and prevent a riot by students at Horace Mann Junior High School. Already recognized as a community leader, Chambers was was elected to the Nebraska State Legislature, serving a total of 38 years.

Riot 4: June 24, 1969

The last notable North Omaha riot happened the day an African-American teenager named Vivian Strong was shot and killed by Omaha police at the Logan Fontenelle Public Housing Projects. Strong and her friends were gathered on a street corner hanging out when an Omaha policeman pulled up. The youth ran, and reportedly without provocation, the attending officer threatened them with his gun. When they kept running, he shot and hit Strong, killing her instantly.

That day, a youth-led organization called the Black Association for Nationalism Through Unity, or BANTU, led a protest that day that is attributed to leading to riots. Crowds of young people reportedly targeted businesses along the North 24th Street business corridor from Cuming Street to Lake Street, throwing firebombs and looting businesses along the way. During this initial surge eight businesses were destroyed, with rioting continuing for several more days. They were quelled by the National Guard by the end of the month, and no further notable riots happened in the city.

- For a detailed history, see my article called “A History of North Omaha’s June 1969 Riot“.

Enduring Legacy

Racism continues to rip apart Omaha’s community fabric today. Many white Omahans point at the ongoing ravages of drugs, gangs, and gun violence as indicators of “what’s wrong with blacks in Omaha”. But history shows otherwise, and in time the community keeps changing.

However, the African American community continues to build in spite, or despite, of the riots. There is a through-line from the enslaved people in Omaha before 1865 to the Jim Crow segregation that was popular from the late 1870s through the 1960s, to the Black political organizing from the 1870s to today, to the lynchings of George Smith and Will Brown, to Omaha’s Civil Rights movement, to the riots of the 1960s and the protests in the 2010s. All of these are related efforts focused on rising, lifting and empowering by Black people for Black people. They are also struggle, challenge, and fight the white supremacy choking the spirit of democracy in Omaha.

For that, white people in the city should be grateful for the riots of the 1960s—they might help heal us after all.

You Might Like…

MY ARTICLES ABOUT THE HISTORY OF KOUNTZE PLACE

General: Kountze Place | Kountze Park | North 16th Street | North 24th Street | Florence Boulevard | Wirt Street | Emmet Street | Binney Street | 16th and Locust Historic District

Houses: Charles Storz House | Anna Wilson’s Mansion | McCreary Mansion | McLain Mansion | Redick Mansion | John E. Reagan House | George F. Shepard House | Burdick House | 3210 North 21st Street | 1922 Wirt Street | University Apartments

Churches: First UPC/Faith Temple COGIC | St. Paul Lutheran Church | Hartford Memorial UBC/Rising Star Baptist Church | Immanuel Baptist Church | Calvin Memorial Presbyterian Church | Omaha Presbyterian Theological Seminary | Trinity Methodist Episcopal | Mount Vernon Missionary Baptist Church |

Education: Omaha University | Presbyterian Theological Seminary | Lothrop Elementary School | Horace Mann Junior High

Hospitals: Salvation Army Hospital | Swedish Hospital | Kountze Place Hospital

Events: Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition | Greater America Exposition | Riots

Businesses: Hash House | 3006 Building | Grand Theater | 2936 North 24th Street | Corby Theater

Listen to the North Omaha History Podcast show #4 about the history of the Kountze Place neighborhood »

MY ARTICLES ON THE HISTORY OF CRIME IN NORTH OMAHA

Crimes: 1891 George Smith Lynching | 1909 Unsolved Murder | 1910 Jack Johnson Riot | 1917 Larkin McCloud Case | 1919 James Smith Death | 1919 Will Brown Lynching | 1969 Vivian Strong Killing | 1960s North Omaha Riots |

Events: Bombings | Mob Violence

Criminals: Early 20th Century Crime Bosses | Vic Walker | Ollie William Jackson | Axe Murderer Jake Bird

Related: Black Police in Omaha | Police Brutality | Antisemitism | Racism

Elsewhere in Omaha: 1906 Murder of Ed Flurry | 1899 Kidnapping of Ed Cudahy | 1890 Pinney Farm Murders

MY ARTICLES ABOUT THE HISTORY OF NORTH 16TH STREET

Places: 16th and Locust Historic District | Charles Street Bicycle Park | State Bar and McKenna Hall | Storz Brewery | Warden Hotel | Grand Theater | Nite Hawkes Cafe | Tidy House Products Company | 2621 N. 16th St. | New Market | 3702 N. 16th St. | Sebastopol Amphitheater

Historic Homes: J.J. Brown Mansion | Poppleton Mansion | Governor Alvin Saunders Estate | Ernie Chambers Court aka Strehlow Terrace | The Sherman Apartments | The Climmie Apartments

Neighborhoods: Near North Side | Lake Street | Kountze Place | Saratoga | Sulphur Springs | Sherman

Events: 1898 Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition | 1899 Greater America Exposition | 1960s North Omaha Riots | “Siege of Sebastopol”

- A History of Racism in Omaha

- A History of Redlining in Omaha

- A History of the June 1969 Riot in North Omaha

Elsewhere Online

- Ashley M. Howard (2006) Then the burning began: Omaha, riots, and the growth of black radicalism, 1966-1969. Omaha: University of Nebraska at Omaha.

- Here is Leo Adam Biga’s account of the riots.

Related Features

- “A look back: The Omaha riots of the 1960s” Jon Kipper KMTV (June 4, 2021)

BONUS

Leave a comment