The government should employ African American people on principle alone. In Omaha government hiring has never been proportionately correct in any department, especially in the Omaha Police Department. But numbers shouldn’t be everything. On principle alone, Black people alone have consistently shown they are consistently more trustworthy, more honest, and more dedicated to democracy than others. This is a history of African Americans in the Omaha Police Department.

Adam’s note: This is not a complete history. Please share details and information in the comments below or contact me!

Taming the Wild West …ish

For almost 25 years, Black people were not police officers in Omaha. The first city marshal was hired in 1857, and despite a continuously growing population of formerly enslaved people, freemen, and Canadian immigrants Omaha did not hire an African American person to serve as a policeman for more than two decades.

Tokenism is defined as “the practice of making only a perfunctory or symbolic effort to do a particular thing, especially by recruiting a small number of people from underrepresented groups in order to give the appearance of sexual or racial equality within a workforce.” Reading the following history, it can be argued that this has been the basis of almost all of the Omaha Police Department’s history of hiring African American members. Regardless, the importance of the contributions of these members and the outcomes of their service cannot be argued: Individually, many were and are outstanding members of the law enforcement community. Following are some of their stories.

In 1880, Omaha had almost 800 Black residents. The first known African American police officer in Omaha was hired in 1881. His name was Frank Bellamy and he worked for the Omaha Police Department from 1880 to 1886. Hired specifically to patrol the segregated Black neighborhood surrounding 12th and Dodge Streets, during his six years on the force Bellamy was credited with many successes. When he resigned in 1886, the newspaper said “Frank was one of the best officers that ever walked a beat in Omaha.” I haven’t been able to locate where Bellamy came from before Omaha. After he resigned, he went on to own a saloon at 10th and Douglas in the Sporting District, and then vanished from the city records.

Other early Black police officers in Omaha in the city included Jesse Newman, who started in 1888. William H. Ransom (1872-1937), Victor B. Walker (1864-c1925), and Noah Thomas (1859-1942) all served before 1900. While most of the officers had jobs less than a decade, Thomas served from 1895 to 1936. Joseph S. Ballew (1857-1923) was a South Omaha police officer between 1900 and 1910.

“I think that you are a disgrace to the force and should be summarily dismissed. There is no use for you to deny the facts, and the best thing for you to do is plead guilty, and step down and out.”

—Police Commissioner Gilbert on Officer Jesse Newman

In 1891, there was a “miniature race war” involving African American policeman Jesse Newman. Officer Newman patrolled 12th Street from Douglas to Chicago Street. Early that April, in a restaurant called the Keystone Chop House at 14th and Dodge, “for several minutes the interior of the long room was filled with bullets, cleavers, flying plates, glasses and knives.” Apparently Officer Newman and two Black companions were told they would only be served in the kitchen of the restaurant, and after a yelling match started fists started flying. Soon after there were a dozen officers at the scene and all of the restaurant workers were arrested. A week later Officer Newman sued the restaurant’s manager for $2,000 for civil rights, discrimination and damages. The manager countersued. The matter was brought to the police board and Officer Newman was charged on five counts: conduct unbecoming an officer for being drunk and using indecent language; beating and bruising a waiter; shooting a customer; and assaulting him (the manager) with a club; and perjury. A trial happened before the police board that included testimony from Sergeant Ormsby, who investigated the event, where he concluded “Newman was not the aggressor and did nothing to precipitate the row.” However, the police commissioner said of Officer Newman, “I think that you are a disgrace to the force and should be summarily dismissed. There is no use for you to deny the facts, and the best thing for you to do is plead guilty, and step down and out.” Fired from his job, almost a month later he was arrested for the assault of a waiter during the event, but in trial the charges were dismissed for having no grounds for the case. Former Officer Newman was represented by Silas Robbins, Omaha’s first African American lawyer. However, by the end of April his case was dropped. According to the Omaha World-Herald, “Newman was asked if he thought he had a poor show to win the suit in view of the failure of previous civil rights suits in this city. He said he had not been discouraged by that.” For a few years afterwards, Newman was referred to in the newspaper as “ex-officer Newman.” He later moved to Oakland, California, visiting Omaha again in 1917 and being noted for his former job again.

Officer Victor Walker (1864-c1925) was a complex figure in Omaha’s history. A Buffalo soldier in western Nebraska, he a political operative in the city after he was a policeman in the late 1880s, and then earned his living as a lawyer. As a criminal defense attorney, he also fought for civil rights issues before the court. However, Walker became involved in the city’s criminal machine and was eventually ushered out of Omaha disgracefully.

Turning the Century

A local authors recently told me there wasn’t much of a line between being a cop and a crook in Omaha in the 1880s. Evidence of this might be apparent in the reality that two of the city’s first Black policemen—Frank Bellamy and Vic Walker—became bar owners in the Sporting District after their service. Walker’s tie-ins with crime boss Tom Dennison were evident and have been documented; Bellamy disappeared shortly after 1900 and is hard to find details about. Regardless, both might have been crooked.

When it was a separate city with a separate police force, in 1915 one of the first African American police officers in the South Omaha Police Department was Joseph S. Ballew (1857-1923).

Harry Buford (1890-1951) was a determined young man growing up in North Omaha. Looking for prospects, he became which led to him becoming a policeman in 1912. Hired as a police chauffeur, Buford became an acknowledged lieutenant of Omaha crime boss Tom Dennison for more than 20 years. By 1930 Buford was a police lieutenant, and although Dennison left Omaha, by 1940 he had become a detective for the city police department. Buford retired as a sergeant detective.

Pitmon Foxall (1910-1986) was an African American officer and detective with the Omaha Police Department for 35 years starting in 1938.

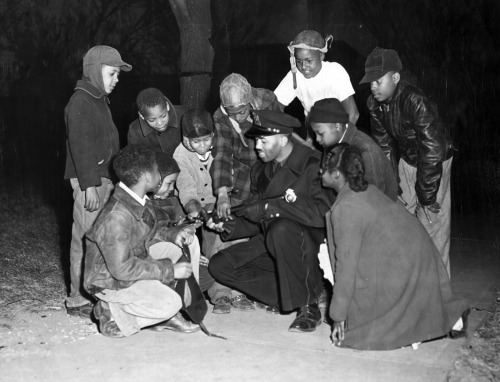

In 1952, John Pierce and Aaron Dailey (1927-1997) became the first African American policemen appointed to “cruiser car duty.”

The Civil Rights movement in Omaha targeted the police force, and one of the four goals of the Citizens Coordinating Council for Civil Liberties, or 4CL, in 1963 was, “That the Mayor direct the police department to integrate squad cars throughout the city; upgrading of Negro personnel and re-education of discourtesy of white officers towards the Negro community.”

Inspiring his nephew Pitmon “Dosh” Foxall II (1930-2000) to become a police officer, Dosh Foxall and Pitmon Foxall worked together in the department for several years. Pitmon Foxall retired in 1973 and died in 1986. Before that, Dosh Foxall became the first field sergeant in the OPD in 1964.

It was an African American police officer who disarmed the white policeman who shot 14-year-old Vivian Strong in North Omaha in 1969. Patrolman Jimmy Smith lived across the street from the Hilltop Housing Projects. After finding his partner with a smoking gun following the killing, Smith tackled the white officer and disarmed him. The shooting led to the 1969 riot that spread throughout North Omaha.

Like his uncle before him, Dosh Foxall had many firsts in the department. In 1953, he was the first African American lieutenant in charge of the homicide unit. He went on to become the first Public Safety Director for the City of Omaha. He died in 2000.

Monroe Coleman (1919-2013) was the first African American captain in the Omaha Police Department in 1964, and in 1966 he became the first Black deputy chief. An officer during World War II and afterward, Coleman joined the department in 1947, serving with his brother William H. Coleman, Sr.. for several years. The younger Coleman was in charge of the security detail for the avowed racist presidential candidate Alabama Governor George Wallace when he came to Omaha. After being forcibly retired in 1981 at age 62, he sued the City of Omaha for age discrimination and won.

Other Black police officers during this era included Isaiah “Zeke” Jackson, Jr. (1939-2021), who served from 1967 to 1997. After starting in 1962, Marvin McClarty Sr. (1939-2015) became a 26-year veteran before retiring in 1988. According to the Omaha World-Herald, “With 13 other black police officers, McClarty started the Brotherhood of the Midwest Guardians in the late 1960s to unite black people serving in law enforcement.” After he retired, McClarty Sr. cohosted a public TV show called “Protecting the Village” with former police officer Tariq Al-Amin for a decade.

Since the 1880s, the number of Black police officers remained minuscule in the Omaha Police Department. In the 1970s, with a racist police union that would not represent their interests, a group of 14 African American officers in the department formed a group to represent their interests called the Brotherhood of the Midwest Guardians. In 1979, they filed a $10million lawsuit against the City for racist hiring practices. The lawsuit forced the City to change its hiring policies, and in 1980 the City had to create an affirmative action hiring plan. With the goal of a 9.5% Black police force equivalent to the total of the city’s Black population, the ruling forced change in the department. It also caused the police to promote African Americans into supervisory ranks throughout the department, which it had not done before.

In 1980, the department hired its first Black female police officer, Brenda Smith.

Dr. Mark Foxall started his law enforcement career in Omaha in the 1980s, then worked for the FBI and the United States District Attorney’s Office in Nebraska before moving to the Nebraska Department of Corrections. After retiring as the Director of the Douglas County Department of Corrections in 2018, he became faculty at UNO and continues there today. Dr. Foxall followed in the footsteps of his great-uncle and his father. According to an Omaha Public Schools project, both of these men “faced a variety of racial challenges on the force in the 1950s and 1960s,” as did “Mark and his brother, who came on to the force during the 1980s, also faced discrimination during that era.”

Another lawsuit in 1986 was supposed to improve African American hiring in the department, but entrenched patterns prevailed and the police failed their marks repeatedly for years afterwards.

However, it would take another 40 years before an African American would lead the department.

New Millennium, Same Issues?

In 2003, Thomas Warren became the first Black police chief since the Omaha Police Department was established in 1857. Warren is Brenda Council‘s brother. He served in the department for 24 years before retiring and becoming the President and CEO of the Urban League of Nebraska. As of January 2023, he is the chief of staff for the mayor of Omaha.

After Warren’s duty was finished, the next African American police chief served 2009 to 2012. In a later interview, Thomas was quoted saying, “As proud as I am to have been the first African American chief of police, I was just as proud we had a second… It was important for me to ensure there would be opportunities for those that followed.”

In 2012 there were more than 75 African American officers in the department.

Simply hiring Black officers does not excuse the Omaha Police Department from its commitment to white supremacy though. It did not prevent the lynchings of George Smith in 1891 or Will Smith in 1919, or prevent the killings of African Americans by police including James A. Smith in 1891 or Vivian Strong in 1969, or five race-related riots from happening between 1919 and 1969, or the KKK from organizing in Omaha. It didn’t stop James Scurlock from being killed while protesting police brutality in 2020. African American officers haven’t made the school-to-prison pipeline in Omaha disappear, and it doesn’t automatically improve community relations with African Americans, people of color, or low-income people throughout the city, either. Police brutality has continued happening throughout the city’s history of hiring Black officers and supervisors within the Omaha Police Department. North Omaha is still disproportionately targeted for “crime fighting” and other euphemisms that cloak the City leadership’s intentions for the community north of Dodge and east of 42nd Street.

Despite the 1979 court case there haven’t been an expansive number of hirings of Black people within the department. African American police officers have reported systemic racism in the department and throughout the City government. There are still police officers in Omaha Public Schools—disproportionately in North Omaha’s schools with predominantly African American student populations, and juvenile incarceration in Omaha still disproportionately affects Black youth, and their sentencing is still disproportionately adverse compared to white youth. There are not enough juvenile diversion programs in Omaha and what does isn’t well-enough funded to truly defeat the prison-industrial complex’s grip on African American young people in Omaha.

At a 2021 event, an African American resident of North Omaha enumerated the issues Omaha police need to do. “Studying your relationship with white privilege. Bias. Identity. Redlining. Food deserts. Racism. Structural racism. Systemic racism. Individual racism. Racial inequality. The school to prison pipeline. Sexism and homophobia. Do the work.”

A History of the Future

However, the department still hasn’t done that. While systemic racism affects those Black police and residents, it also affects white people adversely. By reinforcing white supremacy throughout City government and beyond, the Omaha Police Department forces the moral depravity and reduces the social interdependence everyone benefits from.

Of course, not everyone agrees with that. Instead, publications like The Reader quote anonymous sources saying things like, “Others say Omaha has one of the most innovative and conscious police departments in the country and the city government listens and cares.”

And the criminal justice system continues doing what it does. The City of Omaha government does what it does. And Black people, brown people, and low-income people throughout Omaha continue to suffer.

Despite all of that, African American police continue to bring integrity and determination to protecting and serving the Omaha community. That is a legacy everyone could—and should—be proud of and share widely.

Special thanks to Ryan Roenfeld, author of Wicked Omaha, for his contributions to this article.

Timeline of African American Police in Omaha

- 1857: First Omaha City Marshall hired

- 1881: First African American Omaha police officer hired, Frank Bellamy

- 1915: First African American South Omaha police officer hired, Joseph S. Ballew

- 1952: John Pierce and Aaron Dailey (1927-1997) became the first African American policemen appointed to cruiser car duty

- 1964: Pitmon Foxall, II became the first Black field sergeant in the OPD

- c1969: The Brotherhood of the Midwest Guardians founded

- 1979: The Brotherhood of Midwest Guardians lawsuit forced the City to change its hiring policies and to promote African Americans into supervisory ranks throughout the department

- 1980: Department hired the first African American female police officer, Brenda Smith

- 1986: A lawsuit verdict was given to improve African American hiring in the department

- 2003: Thomas Warren became the first Black police chief

You Might Like…

- A History of Police Brutality in Omaha

- A Biography of Boston Green

- A History of the Case of Rice and Poindexter in North Omaha

MY ARTICLES RELATED TO THE GOVERNMENT OF OMAHA

Streets | Schools | Parks | Public Housing | Police | Firefighters | Eppley Airfield | Streetcars | Public Library

RELATED: CCC Camp | North Freeway

Elsewhere Online

- “OPD History,” Omaha Police Department official website

- “African American Law Enforcement” by the Making Invisible Histories Visible Project of Omaha Public Schools

- Black Police Officers of Omaha official website

- “Black and Badge Talk with Former Police Officer Marlin McClarty [Jr],” Da Hood Table, September 1, 2020

- “Police – 2012 Invisible History” by students in the Making Invisible Histories Visible project of Omaha Public Schools

- “Advocates urge end to school police programs,” Nebraska ACLU official website, July 15, 2020

- “Blue Snitch” website

MY ARTICLES RELATED TO THE GOVERNMENT OF OMAHA

Streets | Schools | Parks | Public Housing | Police | Firefighters | Eppley Airfield | Streetcars | Public Library

RELATED: CCC Camp | North Freeway

Leave a comment