“Mr. Robbins commands the respect of the best lawyers in Douglas County and the confidence of every man who knows him… The result is that he is a lawyer with a fair practice and the possessor of the respect and confidence of his fellow workers at the bar.”

Omaha World-Herald, September 21, 1898

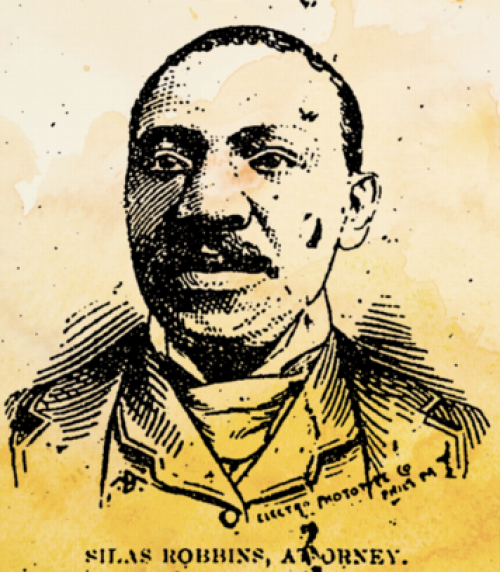

The first African American lawyer in Nebraska had to overcome blatant racism, informal Jim Crow and the white supremacy that has stalked the state’s history since its founding in 1854. He was Silas Robbins.

Born on February 14, 1857 in Ohio, Silas Robbins became a school teacher in Ohio, Indiana and Mississippi. A family of free Black farmers, Silas’s brother became a doctor in Detroit, Michigan. Earning his way onto the bar, Silas was eventually admitted to the Randolph County Bar in 1885, and allowed to practice in front of the Indiana Supreme Court in 1888. After moving to St. Louis, Missouri for a short time, he came to Omaha in the early 1889.

In 1873, the Nebraska Supreme Court ruled that Blacks could not be excluded from serving on juries, paving the way to Robbins becoming Nebraska’s first African American lawyer.

Legal Career

With little fanfare, on March 23, 1889 the Omaha World-Herald reported “Silas Robbins, a fine appearing, bright looking young man was admitted to practice in the district court this morning.”

With that, Robbins became the first African American to practice law in Nebraska, and although it wasn’t until 1892, he was the first African American to be listed on the Douglas County Bar Association. He was one of the first members of the Nebraska Bar Association, which was formed in 1899.

Robbins addressed all kinds of legal issues affecting African Americans in his law practice. From his office in the New York Life Insurance Building in downtown Omaha, Robbins was noted for his “plain manner of fact manner of delivery that succeeded in winning the attention of his audience.”

In an 1890 case, he represented an African American child called Till. Apparently, a farmer in Fillmore County named Williford kept the child as a slave. Robbins fought for his freedom, and after getting the case tried in Omaha instead of Fillmore County, he won it.

That same year, Robbins became the Omaha Afro-American League legal advisor and acted as the secretary for several large-scale Black community meetings chaired by Dr. Matthew Ricketts.

In 1893, he defended an African American man named Alexander Taylor who was accused of shooting at a white man. He was found not guilty.

Newspaper accounts from the era continuously say that Robbins was well-regarded in the legal community, and that he did right for his clients.

Later Life

Robbins was a creative man whose political intentions and speaking abilities kept him busy around town. For instance, after securing a patent from the United States Patent Office for a game he created called “Politics” in 1893, just a year later he was involved in organizing the Omaha School of Economics. According to the Omaha World-Herald, “the object of this school is to study and discuss all questions of political economy and the science of government.” The Rev. John A. Williams and J. H. Kelly were involved, along with Dr. Matthew Ricketts, Dr. W.H.C. Stephenson and others.

During his later years, Robbins was also a regular debater and speaker around Omaha, challenging opponents on federal fiscal policy, local party politics and more. He was the secretary of the People’s Independent Party in 1895 as well.

In 1896, he ran for the Douglas County Auditor office. That same year he became heavily aligned with the pro-silver movement, making speeches and debating opponents throughout the city. Robbins, along with Cyrus D. Bell and John Jeffcoat, led the Afro-American Bimetallic League in Omaha during the pro-growth/pro-inflation Free Silver movement of William Jennings Bryan, starting in 1896. He served as the president of the organization for a few years, which kept an office at 1120 Dodge Street.

Robbins was one of the members of the National Colored Personal Liberty League who was appointed by the Nebraska Governor Governor Silas Holcomb to the Mixed Congress in July 1898. The next month he attended the Mixed Congress at the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition in Omaha. At the event, delegate Robbins represented black clients seeking redress under the state’s civil rights law. After the event, it was noted as “the first significant interracial gathering to discuss civil rights in America.” Many of the Omaha delegates went on to become founders of the city’s NAACP chapter.

That year, in 1898, Robbins ran for the Nebraska Legislature as a “fusion party” member. He didn’t win. Contemporary African American leaders in Omaha during Robbins’ later life included Harrison J. Pinkett, John Adams, Sr. and John A. Pegg, among others.

When the Populist Party took power in Omaha, Robbins was the Douglas County tax commissioner, serving from 1900 to 1901 and again from 1903 to 1905. Afterward he focused primarily on real estate law, and maintained a reputation as one of Omaha’s “best known colored attorneys.”

In 1908, Robbins got a marriage license. Four years later, in 1912 Robbins was sued over the value of some land, and in 1913 he was nominated as the federal government’s special secretary to Liberia. According to the newspaper, he had “the warm endorsement of Mayor Dahlman.” Listed as a member of the Douglas County Dry Campaign Committee, Robbins was signed on to support Prohibition in 1916.

Living at 2883 Miami Street in the Near North Side, Robbins was married twice. His children were Guy, Clifford and Freeda, along with a stepson. Apparently the house at that address today was built in 1905, and was the home were Robbins lived.

Apparently he had a cancer in his head, and in 1915 had a surgery to remove it. However, according to the Omaha World-Herald, he committed suicide on September 11, 1916 by a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head. Both the Omaha World-Herald and The Monitor newspaper attributed it to continued painful suffering from his cancer. Robbins was buried in Forest Lawn.

Today, there is no marker in Omaha celebrating Silas Robbins’ accomplishments as a lawyer or plaque recognizing his historic home. Instead, he’s nearly forgotten across the entire city.

You Might Like…

- A History of Community Leaders in North Omaha

- People from North Omaha

- A History of African American Politics in North Omaha

Elsewhere Online

- “Creating the Color Line and Confronting Jim Crow: Civil rights in middle America (1850-1900)” by David J. Peavler (2008) for the University of Kansas.

- Board game patent by Silas Robbins, 1892.

- Fishing tackle patent by Silas Robbins, 1904.

BONUS PIC

Leave a comment