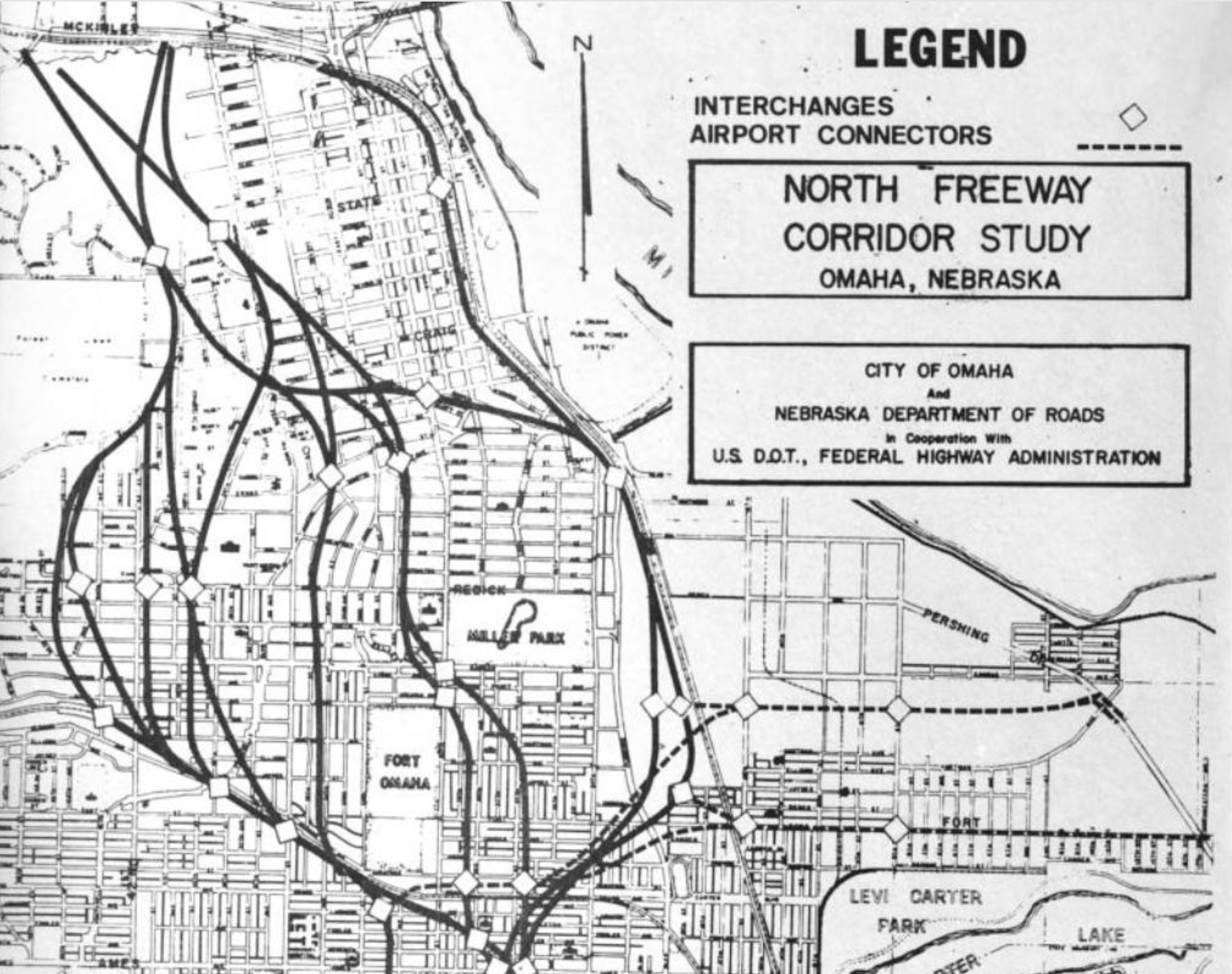

Originally envisioned as an interstate highway to connect I-480 with I-680, the North Freeway is of the most controversial street projects in Omaha history. By developing a major highway through the heart of North Omaha, the government physically sliced Omaha’s historically African American neighborhood in half, leaving a legacy of controversy and discrimination continuing today. This is a history of the North Freeway in Omaha.

Background on the North Freeway

In 1944, Congress passed the Federal Highway Act, which gave the State of Nebraska half of all construction costs to build interstate highways. Ten years later, the payments were raised to 90% of all costs. This was the impetus for the future development of the North Freeway.

It was ten years later in 1954 that the State of Nebraska and the City of Omaha proposed a $2.5-million north-south expressway through the oldest parts of Omaha, including all of North Omaha. Proposed as an economic development project, the North Freeway was intended to speed cattle to the Omaha Stockyard.

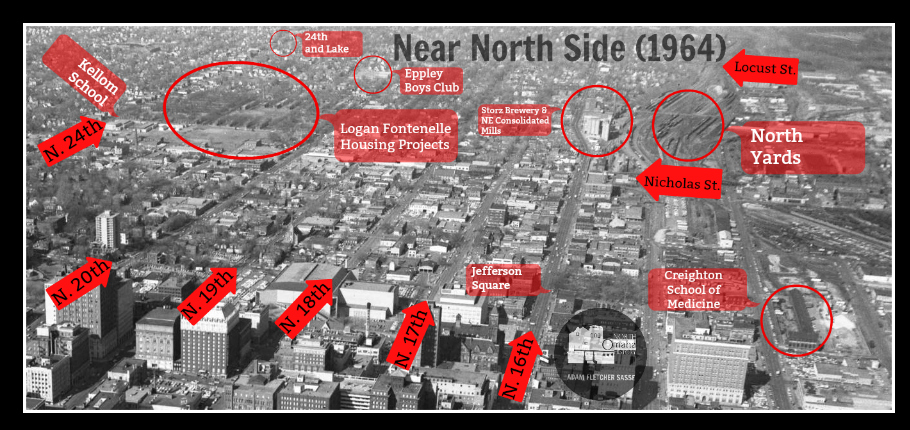

Targeting the Near North Side neighborhood, the new freeway was planned to cut through the Central School neighborhood at North 30th and Dodge Street; slice north through the Montclair and Long School neighborhoods; cut through the Spencer Street Public Housing Projects and the Bedford Place neighborhood; and ultimately obliterate the Saratoga neighborhood.

Concurrent with this planning process was the white flight experienced in each of these neighborhoods: White families were fleeing to western neighborhoods in Benson, Dundee, and northwest Omaha, leaving the community open to more African Americans to move into but removing the white supremacy that immunized the area against radical demolition and “slum clearance” that the City of Omaha had planned for years.

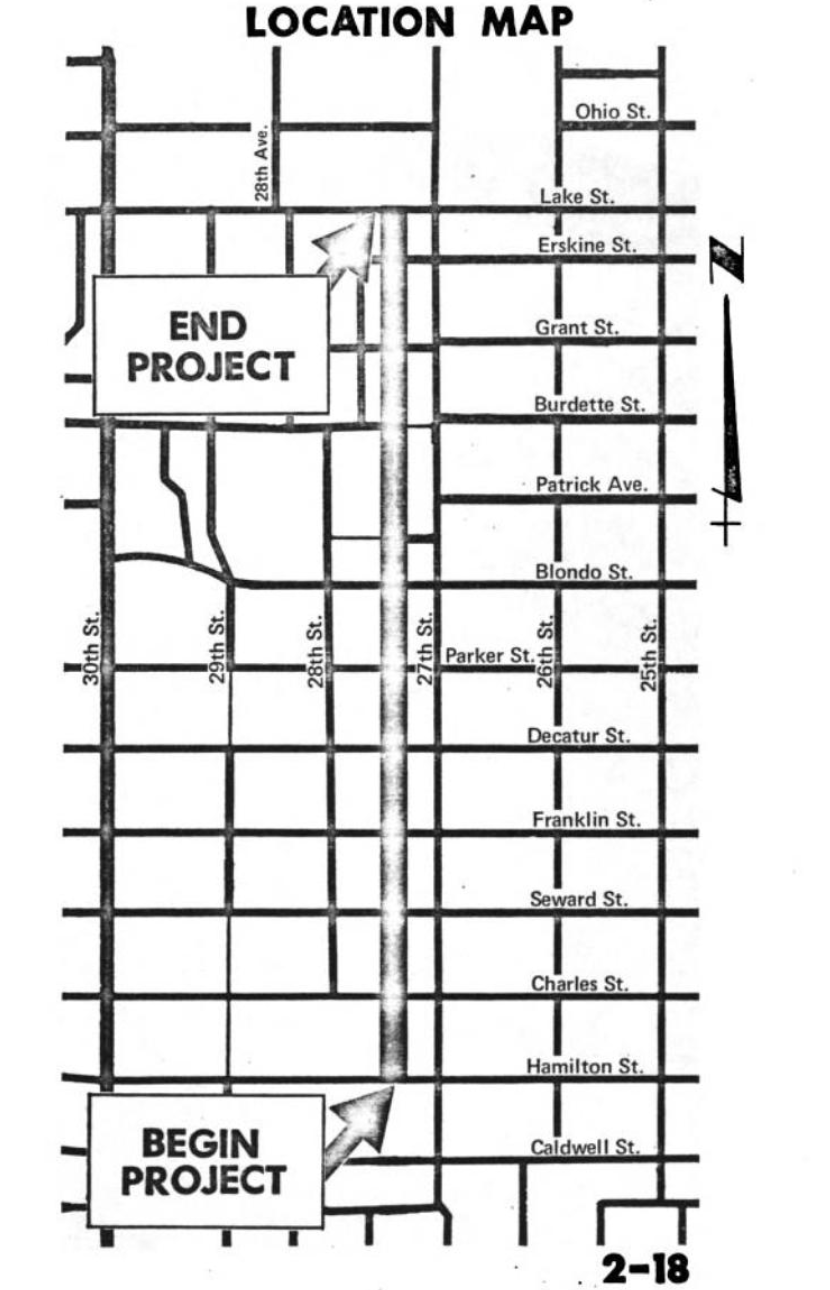

In 1966, Rev. Ted Hottinger (1932-2019) of St. Benedict’s Catholic Church organized a meeting sponsored by the Lake-Charles Community Organization with the City of Omaha planning department. Focused on the impending construction of the North Freeway through the Near North Side, City officials and a State highway planner were scheduled to speak. An open call went out to the neighborhood to discuss the first phase construction happening from Cuming Street north to Lake starting in late 1966, and 1,000 people attended. The concerns voiced at this gathering went largely unheeded by government officials. Regardless, this wasn’t the last time the Black community would share its voice about the North Freeway.

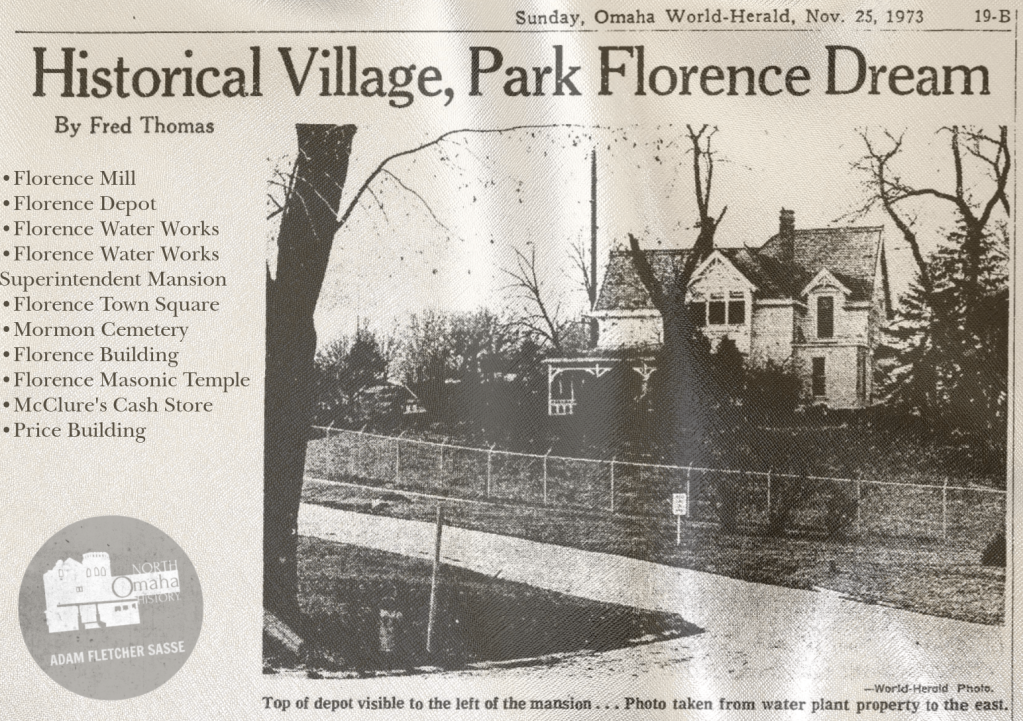

Around 1963, the state extended plans for this expressway to connect with Interstate 680 in Florence. The highway never reached its intended destination though because it was stopped about two miles south of the interstate with community organizing from white neighborhoods. They didn’t want hundreds of buildings in the Miller Park, Minne Lusa and Florence wrecked, including homes and schools and churches. Flexing political force and social influence, activists from these neighborhoods convinced policymakers not to continue the freeway. Many of these same lawmakers listened to the advocacy of African American residents and flatly denied them just years earlier.

After he was assassinated on April 4, 1969, the Omaha City Council considered renaming the future North Freeway in his memory as the Martin Luther King, Jr. Expressway, but didn’t follow through. The issue was brought up again in 1981 and 2003, and again, nothing happened.

After building ramps were from I-480 to connect the highway with a bridge over North 30th Street, planners were forced to re-conceptualize the path after white residents in the Gifford Park and Gold Coast neighborhoods rejected their plans, too.

The North Freeway was designated as Interstate 580 in 1976. However, the City of Omaha rescinded on their agreement to number the highway with that designation in 1979. That same year, they gave back $26million to the federal government because of the halted construction that would’ve extended the North Freeway to I-680. Construction on the North Freeway was halted in 1980. Prior to that, the entire pathway of the North Freeway was dedicated as U.S. Highway 73 / 75; however, the State of Nebraska ended Highway 73 south of Omaha at some point, and removed it from the signage for the North Freeway.

In 1977, the City of Omaha announced plans for the freeway to run north of Lake Street to Ames Avenue. In 1981, 57 units in the Spencer Street Public Housing Projects were demolished to make room for the North Freeway, which was being expanded from Lake Street northward to Sorenson Parkway. The demolished units were replaced with new units in 1983, and Spencer Homes was effectively split into two separate areas by the freeway. That year, the Omaha NAACP youth council hosted a community forum on the construction of the North Freeway, leading the World-Herald to report the event as unsuccessful despite the protests of several editorial writers who insisted it was valuable.

It was 1979 when the City of Omaha demolished the church and school of the Holy Angels Catholic Parish, which was dissolved by the Archdiocese of Omaha. Standing at North 27th and Fowler Avenue, the loss was avoidable in construction but convenient for church decision-makers. White flight had left the surrounding neighborhood largely without Catholic parishioners, and the parish’s demise would be absorbed by the development of new parishes in west Omaha.

The Holy Angels Catholic Parish at North 27th and Fowler Avenue, including its church and school, were demolished to make room for the interchange between the North Freeway, Sorenson Parkway and the Storz Expressway.

The North Freeway was formally dedicated from Lake Street to the new Sorenson Parkway and Storz Expressway in 1998, bookending a planning process begun in 1946. The state used millions of dollars they received for the North Freeway on the Storz Expressway project.

In the final years of construction, the controversial North Freeway was connected to two new high speed roads going northwest and east, the A.S. Sorenson Parkway and the Arthur Storz Expressway, respectively. The Sorenson Parkway and Storz Expressway opened in 1989. The off-ramps from North 30th and the North Freeway were removed in 2005.

Today, the North Freeway is US-75 from the I-480 junction to the interchange with Sorensen Parkway and Storz Expressway.

Effects of the Freeway

Destroying more than 2,000 homes, churches, businesses and other buildings over 34 years of construction, delays, promises, and renegotiations, the North Freeway is still controversial today. This process ultimately led many in the African American community to feel abandoned by the government processes which had ignored, betrayed, or otherwise denied the concerns of some leaders and many residents.

Today, deep resentment still flows through the community because of the North Freeway. There are a limited number of onramps and off-ramps along the route, and most of the amenities associated with interstate travel are missing from the span, including easily accessible tourist destinations, gas stations and hotels, and other useful features. This encourages shopping dollars to forego Omaha’s Black community, instead funneling them southward to the downtown region and beyond.

Ultimately, not completing I-580 gave Omaha enough money for Storz Expressway. Today, the North Freeway is viewed as ” a lesser facility” and the construction of the Storz Expressway is viewed as a win.

Additionally, the inconvenience of the roadway itself continues to mar the community. Without enough pedestrian bridges and with infrequent maintenance of existing bridges, the scar of the freeway serves as a brutal daily reminder of the segregation and indifference of many Omahans towards North Omaha.

The Future

In an official report of the Metropolitan Area Planning Agency called the “Long Range Transportation Plan 2035,” there is a description for a future bridge from East Omaha to I-680 to be built in the future. The report says,

Another new bridge crossing of the Missouri River in this LRTP is along the current 16th Street in northeast Omaha. This would connect a high-speed facility from Storz Expressway to I-680 in Iowa. It would serve to provide easy interstate access to the airport and surrounding industrial area, while also helping to remove freight traffic that currently travels through the Florence neighborhood along Us-75 (30th Street) to access I-680…

-“Long Range Transportation Plan 2035,” Metropolitan Area Planning Agency

…This proposed new bridge across the Missouri River would provide multiple benefits, including providing industries and businesses in northeast Omaha with a direct freeway connection to I-680, potentially opening land in Pottawattamie County to development, and reducing the large volume of truck traffic that travels through the Florence neighborhood along 30th Street (US-75). The potential of attracting new economic development is of particular importance for revitalizing the environmentally sensitive areas in north and east Omaha and Carter Lake. The Gateway Bridge project is estimated to cost approximately $60 million to construct.

While this would continue to protect the Florence community from the development of a high speed roadway, it continues excludes the rest of North Omaha. However, the report makes it sound like a value-added for the community by saying that “it would serve to provide easy interstate access to the airport and surrounding industrial area, while also helping to remove freight traffic that currently travels through the Florence neighborhood along Us-75 (30th Street) to access

I-680.”

All of this construction may continue to have adverse effects on North Omaha and the city’s historically African American neighborhood. It may not. However, no matter how it is perceived today it is undeniable that the damage inflicted on the community has still not been recovered, and the history of the North Freeway will continue to affect Omaha long into the future.

Buildings Demolished for the North Freeway

More than 1,000 buildings were demolished for the construction of the North Freeway, and obviously, this isn’t a complete list. If you know of other structures that should be listed here, please leave a comment.

- Dexter Thomas Mansion, 958 North 27th Avenue

- Central Elementary School

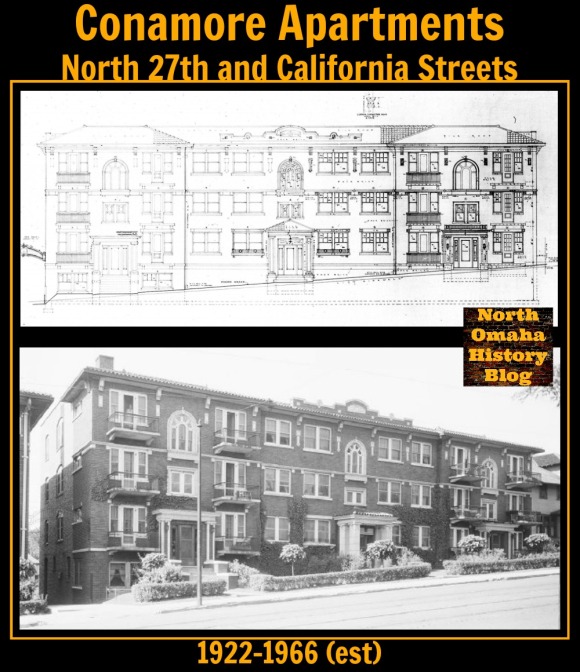

- Conamore Apartments, North 27th and California Street

- Covenant Presbyterian Church

- Hope Lutheran School (1950-1963), 2720 Wirt Street

- Holy Angels Catholic Parish, N. 27th and Fowler Avenue

- Salvation Army Industrial Home, 2734 Caldwell Avenue

North Freeway Timeline

- 1944: The Federal Highway Act of 1944 was passed to provide 50/50 funding from the federal government to states for the construction of a nationwide interstate system.

- 1956: The National Interstate and Defense Highways Act passed to provide 90/10 funding from the federal government to states for the construction of a nationwide interstate system. This was when the North Freeway was first conceptualized.

- 1960: Phase one construction began on the section of the North Freeway from the I-480 interchange near Dodge Street to Hamilton Street. Protests from the Near North Side, Montclair and other neighborhoods failed to stop the construction of the highway.

- 1973: Phase two construction begins from Hamilton Street to Lake Street. Protests from the Long School, Bedford Place, and Kountze Place neighborhoods failed to stop the construction of the highway.

- 1976: The North Freeway was designated as Interstate 580.

- 1977: Phase three construction began from Lake Street to Ames Avenue. Protests from the Miller Park, Minne Lusa, and Florence neighborhoods began, aimed at prevented the continued construction northward to I-680. They succeeded.

- 1979: The City of Omaha requests removal of the I-580 designation from the North Freeway, which was completed in 1980.

- 1980: The City of Omaha and State of Nebraska funneled the money from the interstate construction to the development of the A.V. Sorenson Parkway, and Arthur Storz Expressway.

- 1981: Phase four construction, the final stage, began from Ames Avenue to interchange with North 30th Street, A.V. Sorenson Parkway, and Arthur Storz Expressway.

- 1984: The U.S. Highway 73 designation was removed from the North Freeway.

- 1989: The North Freeway construction was completed and the highway was dedicated.

You Might Like…

- A History of Streets in North Omaha

- A History of the Near North Side Neighborhood

- A History of Railroads in North Omaha

MY ARTICLES ABOUT THE HISTORY OF STREETS IN NORTH OMAHA

STREETS: 16th Street | 24th Street | Cuming Street | Military Avenue | Saddle Creek Road | Florence Main Street

BOULEVARDS: Florence Boulevard | Fontenelle Boulevard

INTERSECTIONS: 42nd and Redman | 40th and Ames | 40th and Hamilton | 30th and Ames | 24th and Fort | 30th and Fort | 24th and Ames | 24th and Lake | 16th and Locust | 20th and Lake | 45th and Military | 24th and Pratt

STREETCARS: Streetcars | Streetcars in Benson | 26th and Lake Streetcar Barn | 19th and Nicholas Streetcar Barn | Omaha Horse Railway

BRIDGES: Locust Street Viaduct | Nicholas Street Viaduct | Mormon Bridge | Ames Avenue Bridge | Miller Park Bridges

OTHER: North Freeway | Sorenson Parkway | J.J. Pershing Drive | River Drive

MY ARTICLES RELATED TO THE GOVERNMENT OF OMAHA

Streets | Schools | Parks | Public Housing | Police | Firefighters | Eppley Airfield | Streetcars | Public Library

RELATED: CCC Camp | North Freeway

BONUS PICS

Leave a comment