Imagine walking up to a few old wagons connected to each other and permanently fixed to the ground, and then having a wonderful dinner at a small restaurant inside. That was the end of several cars from a business once focused on the huge residential areas of North Omaha, providing the fastest way around town for many people. This is a history of the horse railway in North Omaha.

Original Details

The people who incorporated the Omaha Horse Railway Company in 1867 included notable characters like politician Ezra Millard (1833-1886), lawyer A.J. Hanscom (1826-1907), banker Augustus Kountze (1826-1892) and politician Champion Chase (1820-1898), among many others. They were immediately granted a 50-year exclusive deal to operate on the streets of Omaha.

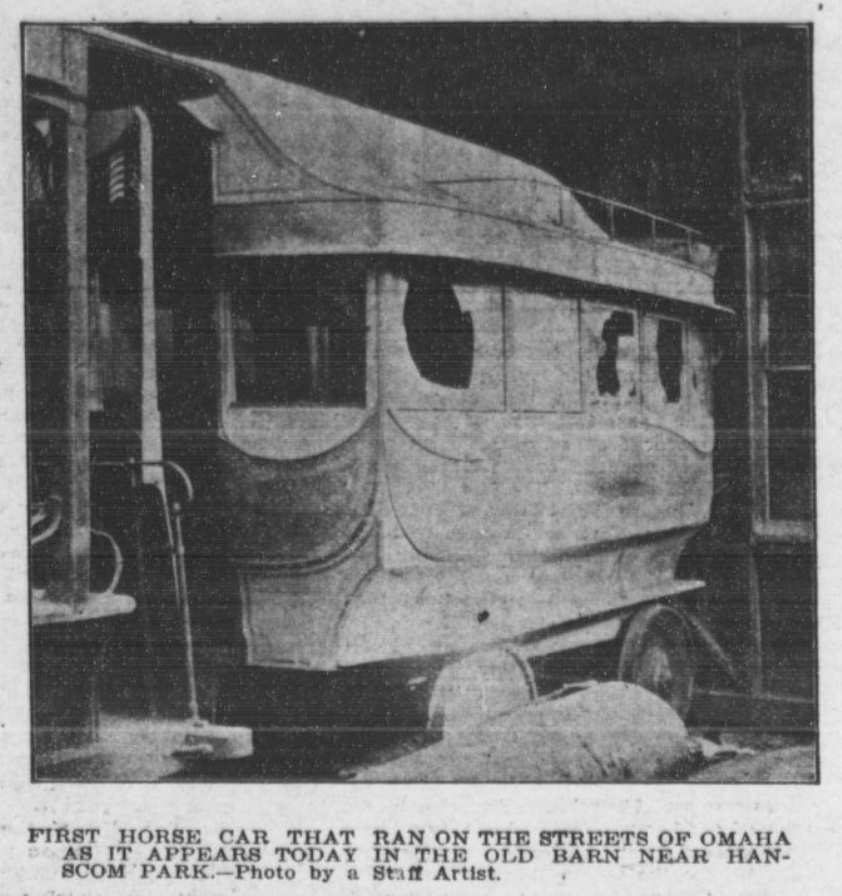

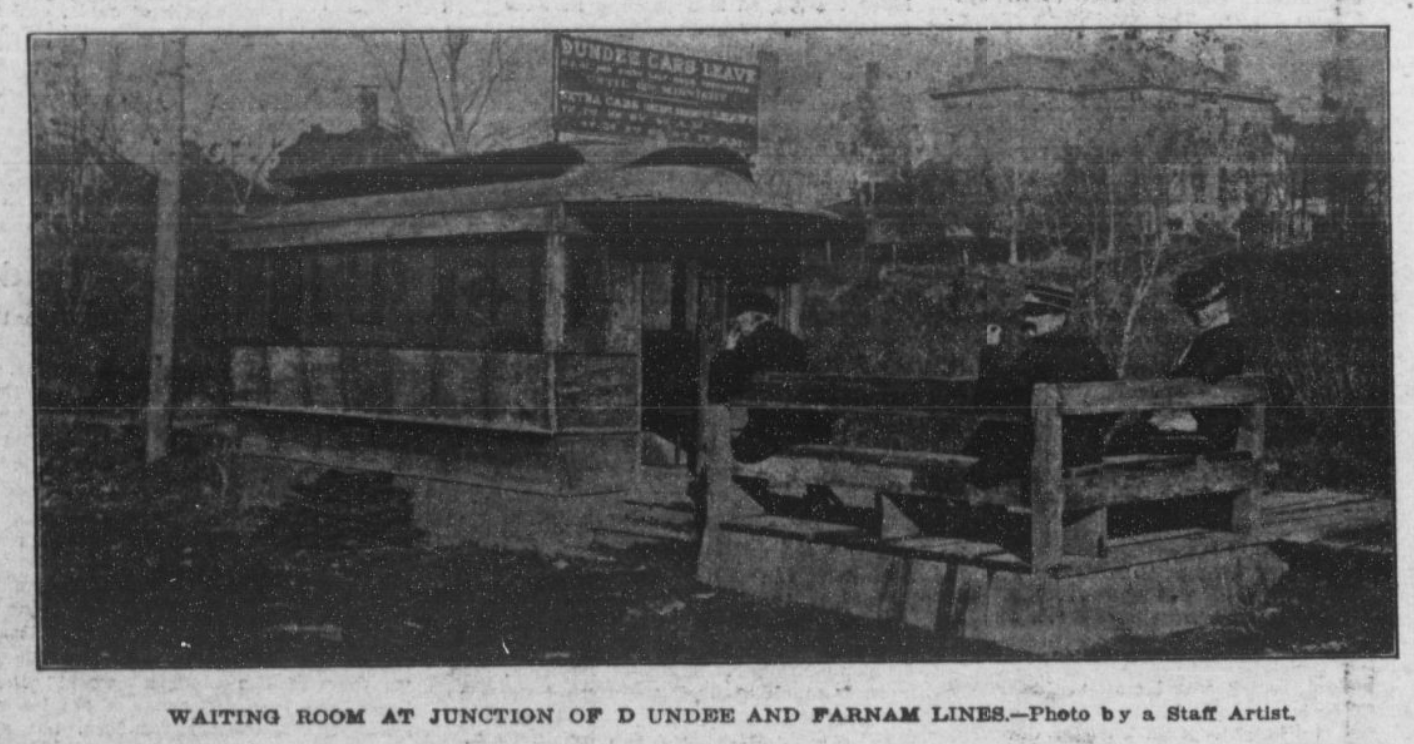

Starting in November 1868, a group of businessmen made the first public transportation system in Omaha, which was referred to as the Omaha Street Railway but formally named the Omaha Horse Railway Company. Crowds stood around and watch when the first rails were laid. They were shaped like a “T” and made of iron, with white oak ties that came in six-foot lengths laid three feet apart from each other in the center of streets. The cars were pulled by horses with bells around their necks to warn pedestrians, and the cars weren’t allowed to go faster than five miles per hour. With two gas-powered lanterns on each of the cars, drivers worked 14 hours per day until 10pm nightly, and the horses averaged 14 miles daily.

The first two miles cost $12,000 to lay. The first barn for the railway was at North 21st and Cuming Street, with 26 horses serving four cars. The first car cost $700, and was brought from Chicago. In 1869, the company bought four 16-foot-long streetcars with a driver and a conductor that needed two horses, and the fare was .10¢ per ride. There was a string across the inside of each side of the cars with a bell tied at the end. A single ring meant to stop at the next intersection; a double ring meant to stop immediately.

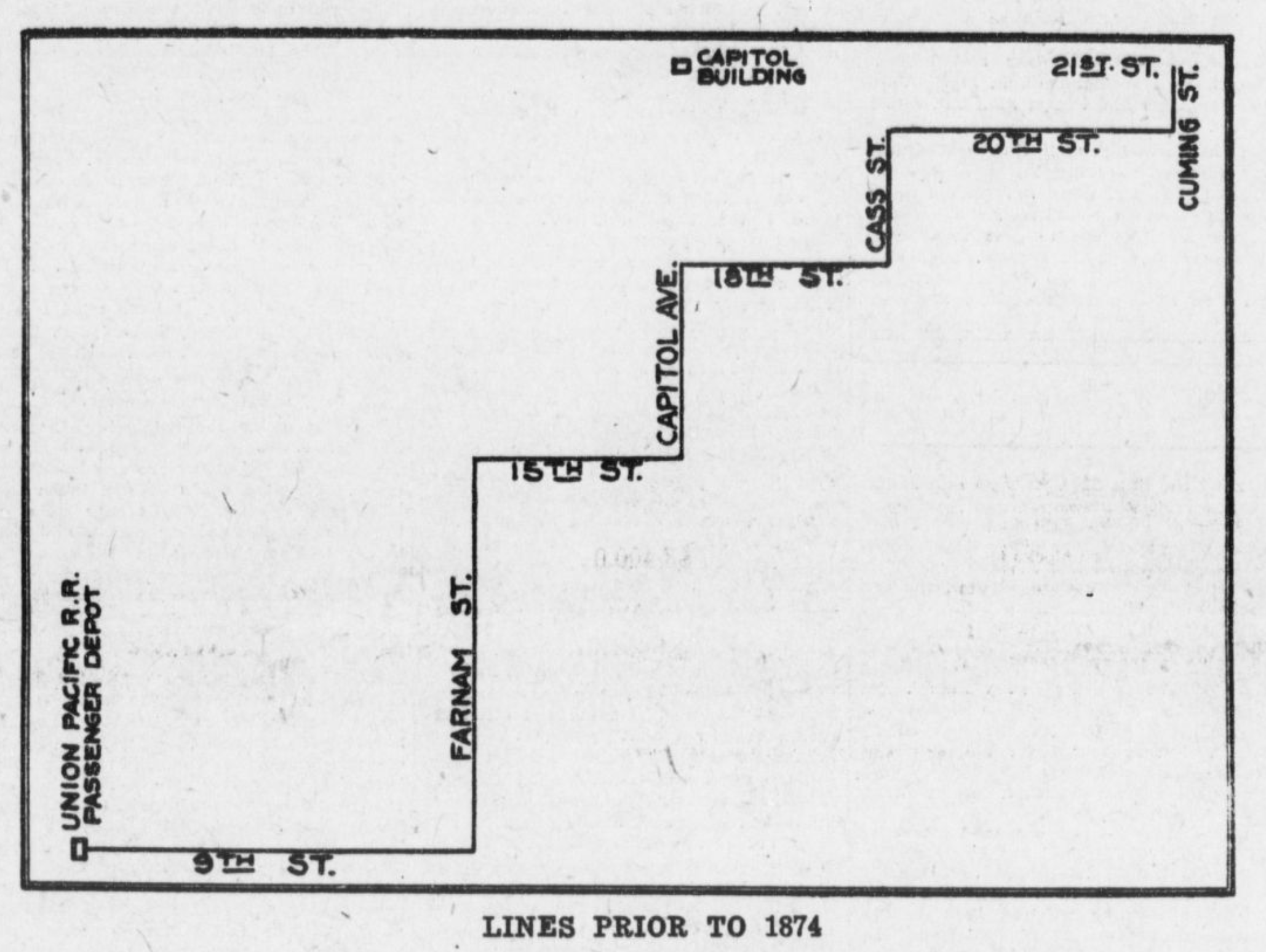

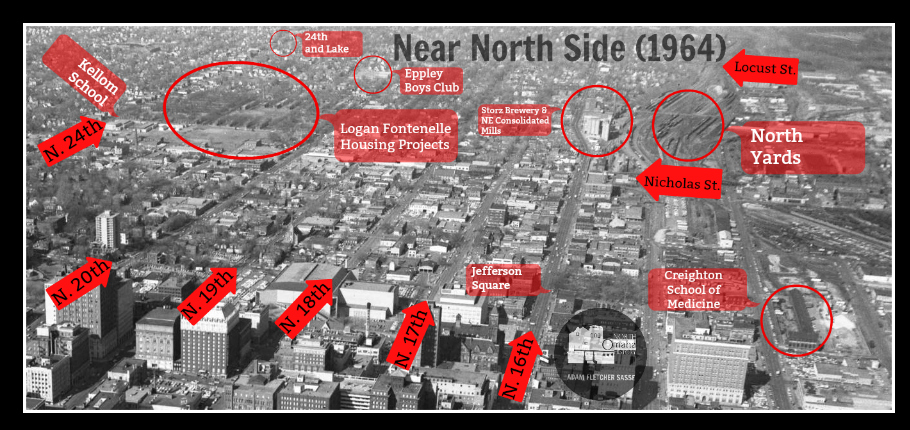

Breaking ground at 9th and Farnam, there were several “first class cars and horses” making trips “every 15 minutes.” With more than 100 workers laying rails and ties, the Omaha Horse Railway’s first routes traveled north to Capital Avenue, North 16th Street, and throughout the Near North Side. They traveled along North 18th Street to Cass, then to North 20th up to Cuming Street. There was also a route to the Union Station. At each end of the entire line, there was a turntable that whirled the cars in the opposite direction to begin their runs again.

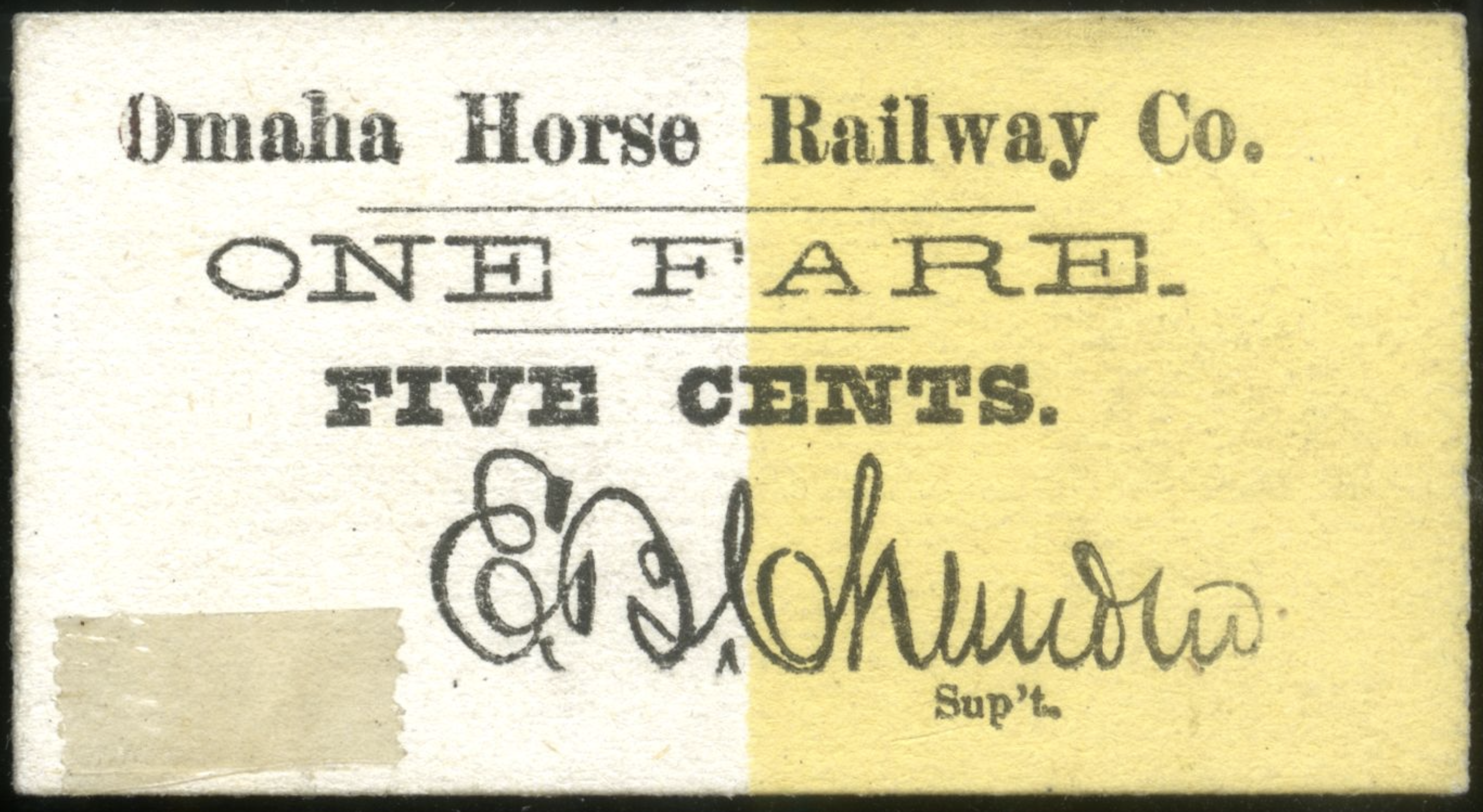

The service didn’t really work though, and required adjustment. In 1872, the company got rid of conductors from the cars and didn’t replace them. They also lowered the fare to .5¢ per ride and one horse from each car. That part didn’t last though because of Omaha’s steep hills downtown, and each car ended up with two horses again. Despite all these changes, the Omaha Horse Railway did not make any profits for the owners, and for five years after it started there was no expansion.

Apparently, Omaha wasn’t the only city in the young state of Nebraska with a horse-drawn railway. Fifteen cities statewide including Lincoln, Nebraska City, Beatrice, Grand Island, Norfolk and Hastings had their own lines, too.

A New Boss

In late 1872, pioneer Omaha lawyer A.J. Hanscom (1828-1907) bought controlling interest in the company, and at the beginning of 1873 named himself president. Later in the year, he sold out to Captain W.W. Marsh (1832-1901), a longtime stagecoach and ferry operator from Council Bluffs. Captain Marsh controlled the company from 1873 until he died in 1901.

Captain Marsh had the original cars painted red right away. Within a year, in 1874 he built a line from the terminal at North 21st and Cuming to North 24th, then north to Hamilton Street. A separate line with cars painted green was built that same year on North 18th from Cass Street to Ohio Street. Marsh’s actions were a gamble because the land north of Cass wasn’t well-developed when he built the line. The next year, in 1875, Captain Marsh built an extension from North 18th to North 16th on Izard Street, then to Capitol Avenue. That car then went on South 10th to the Union Station, forming the first loop in the city. That was the only extension south since the beginning of the company; the Omaha Horse Railway was truly a North Omaha public transportation business.

Neighborhood developers were beginning to wake up to the potential of selling more houses for more money with a regular transportation method serving their houses. For instance, in 1874 property owners in Shinn’s addition pay $4,000 to finance a half-mile extension of the line up North 24th Street. This desire grew slowly, but it grew nonetheless.

During the following years, stockholders in the company foreclosed on their investments because the railway still hadn’t turned a profit. One of them said “…he did not see why Captain Marsh wanted to pay good money for two streaks of rust down streets where there would be nothing in 100 years.” Marsh bought all of the stock and was the sole owner for several years after.

Captain Marsh funded expansion of the line south of Dodge next, including running cars through the cornfields to Hanscom Park for the summer users there.

In 1883, the company reorganized. They had 30 cars all painted yellow with signs showing what line they were on. New stockholders believed in the company, and the company soared through 1889. Omaha boomed all decade, jumping from 25,000 residents in 1882 to 80,000 in 1889. Every neighborhood wanted the Omaha Horse Railway, and the company expanded greatly. The original line extended to North 32nd Street along Cuming, and a North 26th Street line was opened from Hamiliton to Lake Streets. A connector was installed on Lake between North 18th and North 26th, and a North 20th Street line opened from Lake Street to the Omaha Driving Park for a few years. Other lines were opeend on South 13th Street and Farnam Street.

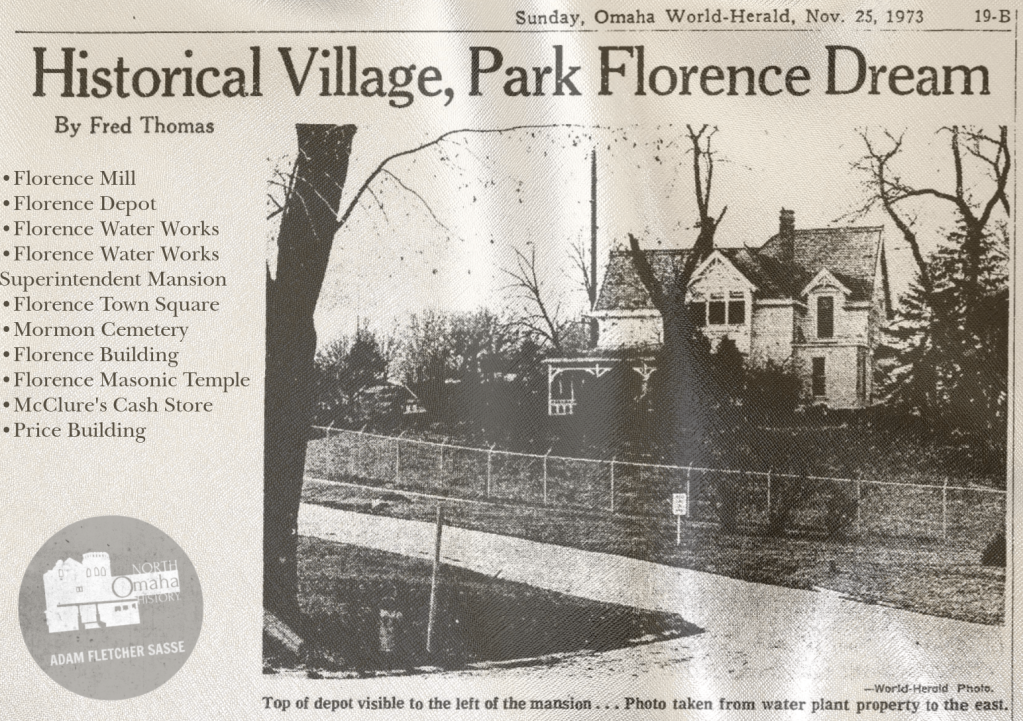

According to the guru of all things streetcars in Omaha, the late Richard Orr, there were 19 streetcar services in various degrees of operation in Omaha and Council Bluffs in 1887. They included the Omaha Horse Railway, the City Street Railroad Company, the Cable Tramway Company, the Belt Line Railway, the Omaha and Florence Street Railway, the Benson Street Railway, the Omaha Cable Railway, the Omaha Horse Railway Company, Omaha and South Omaha Railway Company, the Omaha Southwestern Street Railway, Omaha Motor Railway, the South Omaha Street Railway, The Metropolitan Cable Railway, the Northwestern Street Railway, the City and Suburban Transit Railway Company, and a few others…

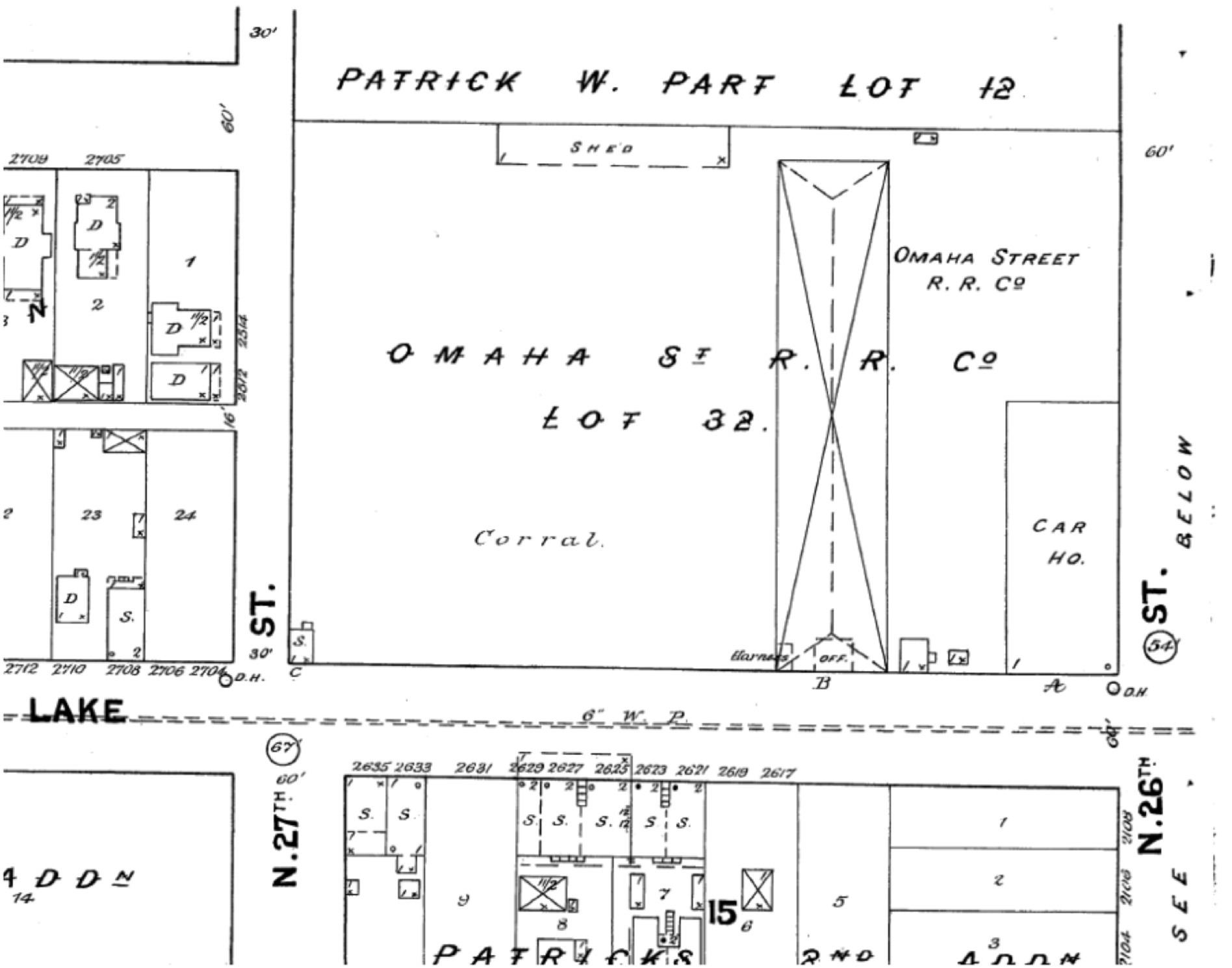

By 1889, a new car barn was built at North 26th and Lake, and two others elsewhere. As the City of Omaha began grading streets throughout the city, the railway changed the type of rail it used, and double rails were installed for the busy route along North 18th Street. Profits were seen by the company, and by 1889 there were about 25 miles of lines, 75 cars and 600 horses with 255 workers for the company.

During that same time period of 1883 to 1889, the cable trolley was introduced on Omaha’s streets and competed directly with the Omaha Horse Railway Company for business. Omahans were nervous about the new service for a while though and competition was healthy. West of the Mississippi, only San Francisco and Kansas City went before Omaha in trying this innovation, which was expensive and unproven. At the same time, electric streetcars were introduced in Omaha, and competition became very stiff. There was tension between each of the modes, and conflict happened regularly. The cable company ran tracks on either side of the horse tracks on North 18th and North 20th, and at North 30th and Ames there was a huge fight between workers expanding both companies’ rails.

Other notable people who owned shares throughout the life of the company included real estate mogul Byron Reed (1821-1891), politician Alvin Saunders (1817-1899), politician James E. Boyd (1834-1906), businessman J.J. Brown, politician Moses Shinn, Edgar Zabriskie and Charles F. Manderson.

The End of the Horses

In 1889, there were four sets of tracks on North 20th Street between Cass and Cuming. That year, the Omaha Horse Railway took the Metropolitan Cable Tramway to court for crowding out its rails. The judge ruled in favor of leaving the tramway’s rails, but made them pay a fine to the horse company. This was a notable case nationally, because it allowed the company to assert its exclusive franchise rights and encouraged others to do the same nationwide.

By this point, the Omaha Horse Railway Company had installed a turntable south of Dodge Street that became “the center of all business on the horsecar line.” They still had barns at North 21st and Cuming and North 26th and Lake Streets though.

That same year, three companies with different technologies competed for Omaha’s public transportation customers. The Omaha Horse Railway had 25 miles of track; the Omaha Cable Tramway had 6 miles of double cable tramway, and; the Omaha Motor Railway had 10 miles of double track electric road. The horse railway company decided to install cable AND electric power on their lines.

In February 1889, the Nebraska Legislature passed a law allowing the merger of the horse and cable companies, and in April it happened. Operating as a single system called the Omaha Street Railway Company, they competed against the Omaha Motor Railway Company. From that point forward, the Omaha Horse Railway Company ceased to exist ever again. In October 1889, the Omaha Street Railway Company bought the Omaha Motor Railway Company and consolidated all of the trackage, routes and services. That fall, a terrible equestrian disease killed a lot of horses owned by the company, seemingly spelling the ultimate failure of relying on natural horsepower for public transportation.

A new bridge was built over the river in 1889 and new electric streetcars were introduced for the first time by the Omaha and Council Bluffs Railway and Bridge Company. Eventually, the 16-foot cars of the horse-drawn railway were replaced by 40-foot cars by its replacement. It took another decade, but eventually in 1898 the public transportation system in Omaha became profitable.

While 1889 marked the end of the horse company, it wasn’t the end of horses on Omaha’s streets. According to research by Jody Lovallo, there were horses in regular use throughout the city into the 1940s, long after cars became popular in the 1910s. In 1909, Nebraska City was the only horse railway in the state; Lincoln and Omaha were the only cities with streetcars by then.

Today, there are no known signs that the Omaha Horse Railway Company ever provided outstanding service to the North Omaha community. However, its clear that without them the busy, bustling neighborhoods that once filled the region from Dodge Street to Lake Street, from North 16th to North 24th Streets would have had a much harder time getting around.

You Might Like…

- A History of Streetcars in North Omaha

- A History of Streetcars in Benson

- A History of the Nicholas Streetcar Barn in North Omaha

- A History of the 26th and Lake Streetcar Shop in North Omaha

MY ARTICLES ABOUT THE HISTORY OF STREETS IN NORTH OMAHA

STREETS: 16th Street | 24th Street | Cuming Street | Military Avenue | Saddle Creek Road | Florence Main Street

BOULEVARDS: Florence Boulevard | Fontenelle Boulevard

INTERSECTIONS: 42nd and Redman | 40th and Ames | 40th and Hamilton | 30th and Ames | 24th and Fort | 30th and Fort | 24th and Ames | 24th and Lake | 16th and Locust | 20th and Lake | 45th and Military | 24th and Pratt

STREETCARS: Streetcars | Streetcars in Benson | 26th and Lake Streetcar Barn | 19th and Nicholas Streetcar Barn | Omaha Horse Railway

BRIDGES: Locust Street Viaduct | Nicholas Street Viaduct | Mormon Bridge | Ames Avenue Bridge | Miller Park Bridges

OTHER: North Freeway | Sorenson Parkway | J.J. Pershing Drive | River Drive

Elsewhere Online

- Omaha Horse Railway on Wikipedia

- “Omaha Horse Railway Bond” from Omaha in the Anthropocene

- “Omaha Horse Ry. Co. v. Gable Tramway Co. of Omaha.” (March 5, 1887) Circuit Court, D. Nebraska from the Federal Register.

- “Horse Car Days and Ways in Nebraska” by E Bryant Phillips in Nebraska History 29 (1948): 16-32.

BONUS

Leave a comment