Black empowerment has long been associated with economics, ownership and fiscal ability. As a white person, I do not and cannot understand this fully, and what follows is a well-meaning, if misguided, attempt to share my half-understanding with others. I have not found another history of this type, and I am committed to sharing the under-reported history of North Omaha, of which Black-owned businesses are an essential part. If I’ve messed up here, I hope you will leave a note in the comments and share any criticisms, additions, corrections or otherwise. Also, please share this history with others. This is a history of businesses owned by African Americans in Omaha.

Summarizing Historic Black Entrepreneurship in Omaha

By claiming to be a history of African American businesses in Omaha, this article has to begin with the acknowledgment of racism and the usage of white supremacy to stifle the economic mobility of Black people throughout the city’s history. Despite that, African Americans have built, owned, sustained and thrived in business since before the Civil War.

In Omaha, the first Black business owner might have been Bill Lee, who opened the first barber shop in Omaha in 1856. His business was located in the Douglas House, a hotel, at 1301 Harney Street. Over the next 40 years, African Americans owned a number of businesses downtown, in the Near North Side, and south of downtown. They included blacksmithing, laundries, barbershops, pool halls and drinking establishments. African Americans in Omaha also owned tobacco stores, and ran businesses as shoemakers and dressmakers.

In the second decade of the city’s history, Black storeowners and restauranteurs started opening businesses.

It was the 1870s when the professional class started to emerge among Omaha’s Black community. Early lawyers and doctors led the way with entrepreneurs close behind. People such as Dr. Matthew Ricketts (1858-1917), lawyer Silas Robbins (1857-1916), entrepreneur Thomas Mahammitt (1862-1950), dentist Dr. Craig Morris (1894-1977), and newspapermen George Franklin (18??-19??) and Cyrus D. Bell (1848-1925) helped form the Black business ownership class in Omaha. African American undertakers were an important part of this emerging social class. J. H. Russell (c.1861-c.1893) along with Annie Banks (18??-c.1943) and Cecil Wilkes (18??-1947) were some of the earliest Black undertakers in Omaha.

Later lawyers included the groundbreaking Elizabeth Pittman (1921-1998), who opened the first African American woman-owned law firm in Omaha in 1950, as well as the father and sons firm of John Adams, Sr. (1876-1962), John Adams, Jr. (1906-1999), and Ralph W. Adams (1911-1968).

There were more complicated figures among Omaha’s early Black businesspeople, too. One of them was Vic Walker (1864-c.1920), an old-school lawman who became tied up in Tom Dennison’s racket in the 1890s. While becoming a successful businessman, he also worked as a lawyer in Omaha’s courts. He was ridden out of town on a rail, and moved on to Denver to continue life there.

According to historian August Meier, during this era whites stopped shopping at Black businesses, and, “Depending upon the Negro market, the promoters of the new enterprises naturally upheld the spirit of racial self-help and solidarity.”

20th Century Omaha

An 1899 Omaha World-Herald article reported 2,000 African American business owners nationwide, but didn’t share numbers in Omaha. The city was far from an ideal environment for Black-owned businesses, especially when compared to Harlem’s Striver’s Row and Tulsa’s Black Wall Street.

However, by this point Black-owned businesses had long been seen as important in North Omaha. In 1909, after returning from a national gathering community leader John Grant Pegg (1868-1916) helped establish the Omaha Negro Business League. Intended to encourage business development and “stimulate race pride,” the organization was led by Pegg, along with Harvey Saunders (18??-19??), undertaker G. W. Obee (18??-19??), real estate agent Alphonso Wilson (1860-1936), Dr. A. G. Edwards (18??-19??) and Dr. J. H. Hutton (18??-19??).

The first all-Black movie production company in the United States was founded in North Omaha. In 1915, brothers Noble (1881-1976) and George Perry Johnson (1885-1977) created the Lincoln Motion Picture Company, soon moving to Los Angeles but maintaining strong distribution from Omaha. According to the Omaha World-Herald, for the six years the company ran it made, “films that rebutted negative stereotypes of African-Americans and sought to convey the fullness of Black life in America.”

Omaha’s Black community made national news in 1920 when a group of African American investors launched the Kaffir Chemical Laboratories Corporation. Raising $500,000 to start, the company proudly touted it was financed by “race capital.” The company manufactured pharmaceuticals, chemicals, drug preparations, and medicines. Its early catalogue included hair tonic and more products created for and marketed to African American consumers, and their brands included Dentlo toothpaste; Kaffir Kream skin cream; Sultox stomach medicine; and Rem cold medicine.. Rev. John Albert Williams was one of the investors and leaders of the corporation. Despite a fire ravishing their labs in 1921, the company kept going, but ultimately folded in 1925. Their building, called the Kaffir Block, was in a former hotel and stood at North 16th and Cuming Street.

In 1920, the Colored Commercial Club was established in 1920 to select and both men and women for prospective employers, and to encourage the establishment of Black businesses in North Omaha. In the 1940s, the Omaha Urban League took up this challenge, fighting for Black jobs throughout Omaha and supporting Black-owned businesses in a variety of ways.

A Black-owned business opened explicitly to serve North Omaha’s African American community in 1920, the Cooperative Workers of America (CWA) Department Store had big ambitions. In an article about its opening, the store said it planned to “give employment to from thirty to forty young women and young men.” “Colored people must enter the higher forms of modern business, just as other races have been doing for hundreds of thousands of years, and they must take the best features of business organization…” However, it closed permanently less than 18 months after it open, shuttering its windows for the last time in November 1921.

Black newspapers were long important businesses unto themselves, as well as important for other Black businesses. Starting in the 1880s, there have been a dozen Black-owned newspapers in Omaha history. Rev. John Albert Williams (1866-1933) used his newspaper called The Monitor to drive North Omaha economics, calling frequently for readers to support Black-owned businesses. In 1938, the Omaha Star became one of the main media drivers for Black-owned businesses in Omaha. Editor Mildred Brown (1905-1989) called the absence of Black patronage of Black businesses an “economic lynching.”

In the late 1930s and 1940s, the Omaha Star sponsored an annual Cooking, Business and Social Exposition at the Dreamland Ballroom. Featuring booths from “all the Negro owned grocery stores in the city,” there were also booths for Black-owned newspapers from across the city and the Housewives’ League. The Marjorie Ware (19??-19??) School of Dancing presented exhibitions each of the three nights, and there were demonstrations from “commercial houses” including Butter-Nut Coffee, Robert’s Dairy, several breweries, and Paramount Radios. There were also drawings and a baby contest.

Starting around 1925, the Omaha Negro Chamber of Commerce acted as a liaison between Black and white businesses throughout the city. In 1939, the co-founder of the Omaha Star, S. Edward Gilbert (1903-1976), became president of the Chamber. The next president was attorney John Adams, Sr. (1876-1962), who led the Chamber in creating a report about African American business and professional activities in Omaha. The report was presented in luncheons with Omaha press, labor and professional groups with the intention of building support and improvements with white Omahans.

A 1932 report on Black business and industry in Omaha said there were six main changes benefiting African Americans in the city at that point:

- Accumulated experiences in industry;

- Expansion of Black-owned businesses;

- Entrance of Blacks in new occupations;

- A growing feeling of race consciousness;

- Changes in employers’ attitudes; and,

- Increasing political influence among African Americans

That same report stated there were 94 businesses owned by African Americans. They included 16 coal and ice companies; 15 deliverymen; 10 beauty professionals; nine pressing and tailor shops; eight grocery stores; eight restaurants and eight barber shops; six garages and five real estate agents, among others.

“When you see a Negro business that is worthy and a credit to the race and the community in which it is to be found, pitch in and help it grow.”

– “Bigger and better Negro business,” Omaha Star, September 27, 1940

In 1971, a national directory listed 307 Black-owned businesses in Omaha. According to the directory, “The overwhelming majority of Black-owned businesses in the city are small service-type businesses.” Among the businesses with the most representation were 23 beauty parlors, 20 restaurants, 15 service stations, 16 delivery services, seven shoe shine parlors, three architects, and one accountant listed.

Friction

There hasn’t been a lot of agreement about whether Black-owned businesses are a silver bullet for empowering African Americans in Omaha. For instance, in 1950, a Black businessman in Omaha named Lynwood Parker (c.1920-19??) said Black-owned businesses can’t solved Black unemployment and underemployment. He said, “It emphasizes division and separateness [and] could be the seed for further friction.”

During rioting that happened in April 1968, the Omaha World-Herald reported that L and V King Cleaners was the only Black-owned business that was damaged. $500 in windows were broken, which the owner suspected happened because the building had the former white owners’ signage on it still. During the June 1969 riots, the Omaha Black Panthers actively protected Black-owned businesses along North 24th with rifles and their presence.

“My husband and I bought the business last year,” Mrs. King Said. “I thought since I was a soul-brother they wouldn’t bother my store.”

-“Store owners will try once more,” April 30, 1968 Omaha World-Herald

Black businesses in Omaha have never been devoid criticism, either. In addition to the occasional boycott and protest, larger efforts were made to challenge African American business owners, too. For instance, among club owners in the 1950s there seemed to be constant pressure about pandering to white audiences. The same motivation might have been behind the bombing of the Black-owned Component Concept Corporation in 1970. Alternatively, the bombing might have been setup to indict the past leaders of the Omaha Black Panthers in a serious crime, simply using a Black-owned business as a convenient ruse.

Racism in Omaha Business

The historical record shows that white supremacy has constantly burdened Black-owned businesses in Omaha, and despite of it or in spite of it, African American business owners have been successful. Accused by white buyers of selling lower-quality goods at higher prices, white media and other sources routinely insulted Black businesses and insulted African American consumers. Without making any formal rules or laws, an “understanding” settled over Omaha that with few exceptions, whites didn’t shop from Black-owned businesses. These kinds of “understandings” are called de facto segregation. Even as Black entrepreneurs moved into white neighborhoods throughout the Near North Side and beyond, this segregation still existed. In 1938, the Omaha Star observed that although the black community provided 75 to 95% of the business for establishments along North 24th Street, few blacks were hired or owned businesses along the strip.

Industries such as real estate and banking in Omaha have long been segregated too, practicing racial and economic discrimination as a keystone of their practices. Frequently colluding, there have been laws and rules made to prevent their actions, but from the 1920s through today (2019), the evidence of their white supremacy is obvious through racial segregation and more.

Criticism of racism within the Omaha business communities continues into modern times. In March 2011, late community advocate Matthew Stelly (1954-2019) targeted development in North Omaha by suggesting “white folks talk about tangible things, money capital growth, tax incremental financing, bricks and mortar, etc.” while Black people in the community were stuck with the “maintenance of segregation, the ongoing underdevelopment of North Omaha, the duping of tens of the thousands of Black people by the City of Omaha Planning Department, and the betrayal of the community by ‘negroes’ who ought to know better.”

Black-owned businesses in Omaha were also targeted by the Omaha Police Department constantly, too. For more than 60 years from the 1890s through the 1950s, a “morals squad” patrolled North Omaha bars, clubs, barbers, shoemakers, pool halls, and other Black-owned businesses for illegal activities, oftentimes trumping up charges including “Keeping an immoral house,” illegal gambling and gaming, and other activities that may or may not have been happening. In 1930, the experience of African American business owner William B. Wallace (c.19??-c.19??) summarized what happened to many Black business owners in Omaha. After his cigar store was raided by the Omaha Police Department for the fifth time, he accused the department of targeting him with false charges. There are frequently charges against Black businessmen listed throughout the city’s historic newspapers.

One study found, “Though the Near North Side served as a business location for small time entrepreneurs to build their stores, in 1965, fifty percent of all buildings located along a ten block strip from Ames to Cuming Streets along North 24th Street remained vacant.”

The 1971 directory mentioned earlier included reasons why Black-owned businesses didn’t thrive in Omaha, all linked to racism in the city. They included,

- Absence of capital investment available to white businesses;

- Lack of acceptance as suitable provider of goods, products or services by white businesses;

- Technical assistance for business operations open to white businesses unavailable to Black-owned businesses; and,

- Unequal opportunities to compete for government and private industry contracts.

In 1970, a Black entrepreneur named Wayne Harris (1936-????) secured more than $1,000,000 in grants from the federal government to develop a modern shopping center at North 30th and Pinkney Streets. However, after struggling for more than a year to secure a major grocery store as an anchor for the center, he had to abandon his plans. He cited several factors affecting his success. They included,

- A lack of confidence in African American businessmen by white investors;

- Difficultly obtaining insurance because of civil disturbances;

- “Tight money situations” in local banks due to recession, and;

- Questioning the economic value of proposed businesses and the economic possibilities of North Omaha.

In a city as segregated as Omaha is and has been though, its important to point out the obvious: African Americans own businesses today and have owned many businesses in the past.

Types and Examples of Black Businesses in Omaha

“Dollars spent outside our community never return, they don’t create any jobs or wealth, it merely depletes our resources. Instead, if we can increase those resources, we’ll have a better chance of rebuildings our community in the 21st century.”

-NAACP Juneteenth Black Business Expo Flyer, 1991

There have been a variety of Black-owned businesses throughout North Omaha’s history. Some defy single categories, like the business belonging to Smith Hines (1866-1942). He was the African American owner of a pool hall, restaurant and barber shop at 10th and Capitol for several years. However, I’ll group the obvious and other types of businesses and examples of the African American owners in each type below.

Black-Owned Restaurants and Food Businesses

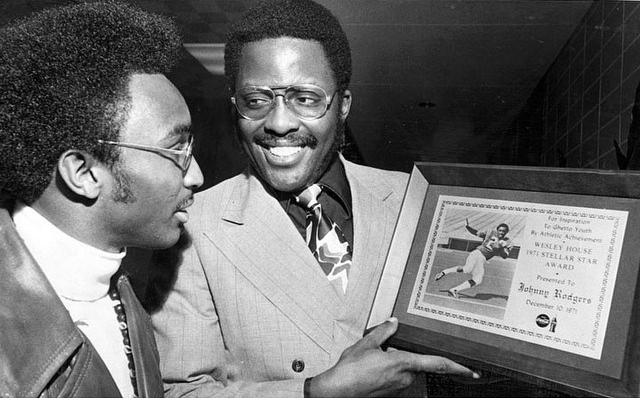

There have been many Black-owned restaurants in Omaha’s history. One of the oldest Black-owned restaurants in Omaha is Time Out Foods at 3518 North 30th Street. Opened in 1969, it was first opened by the Swanson Corporation and promoted by Bob Gibson (b.1935) and Bob Boozer (1937-2012), professional sports stars from North Omaha. In 1972, it became family-owned and operated, and it continues today in its original location.

Other Black-owned restaurants in Omaha history have included Metoyer’s BBQ, Carter’s Cafe, Skeet’s Barbeque, Fair Deal Cafe, Tic Toc Diner and the Live Wire Cafe.

In the 1920s and 30s, George East (18??-19??) owned a barbeque stand at 1502 Burt Street. Victor Metoyer, Sr. (1899-1986) opened a barbeque restaurant at 2311 North 24th Street with Alton Goode (1897-1986) in 1958, then ran it solo for more than 30 years until 1985. Harold C. Whiteside (1912-1978) opened his BBQ restaurant called Skeet’s in 1956. David Deal (1952-2019) took over in 1978 and ran it until he died in 2019, when the restaurant closed permanently. In 1972, Skeet’s was named the best BBQ in America by Preston Love, Sr. (1921-2004), who traveled the nation as a musician, eating BBQ everywhere he went. In the same article, he reviewed the history of Black-owned BBQ stands in North Omaha. They included the “BBQ King” Mr. Slaughter’s (18??-1949) Barbecue Hut at North 24th and Blondo Streets from the 1920s through the 1940s, and Gertrude’s, who inherited the family recipes after Mrs. Slaughter died. Jeff’s BBQ at North 24th and Nicholas was popular with musicians, and Clara’s was popular, too. Jack Craven’s and the Father Divine’s disciples called “Peace” sold good BBQ, too.

The Fair Deal Cafe was an iconic Black-owned business on North 24th Street for almost 50 years. Charlie Hall (1930-2009) and his wife Audentria “Denny” (1933-1997) opened it in 1954, running the establishment almost solely until it closed in 2003. The Fair Deal was called Omaha’s “Black City Hall” for all the business, political and social action that happened there. Carter’s Cafe was opened by Lucy Carter (1901-1983), and stayed in business from 1953 to 1983. Leroy (19??-19??) and Ethel Webb (1924-1991) opened the Live Wire in the late 1950s, moved it up North 24th in 1968, and kept it running until 1986. The Tic Toc Diner was opened by Lillian Oliver (1909-1990) and her sister Clara Leonard (19??-19??) in 1953 and closed permanently in 1997. Each of these was a Black-owned business.

There have also been several successful Black-owned caterers in Omaha, including Alfred Jones’ Hillcrest restaurant from 1923 to 1936. The husband and wife team of Thomas and Helen Mahammitt ran a catering business from 1905 to 1950, and Mrs. Mahammitt ran a cooking school in North Omaha and wrote a book.

African Americans have owned many franchises in North Omaha, too. For instance, Albert Tibbs owned a Diary Queen franchise at North 24th and Blondo streets from 1955 to 1963. Early in 2019, Julian and Brittany Young became the first African American owners of a Scooter’s coffee franchise. Their shop at 30th and Ames has been popular since opening.

Black-Owned Grocery Stores

There have been many Black-owned grocery stores in North Omaha history. For instance, Race Grocery was located at 2754 Lake Street, and was owned by African American James Coquit. He offered fresh food, groceries and meats, and specifically sold to African Americans, who were regularly discriminated against by white-owned grocerers in the Near North Side. In the 1910s and 20s, Marsh’s Market at 1324 North 24th Street was owned by an African American, along with Rite Way Groceries at North 24th and Patrick Streets. Dave’s Market was at 24th and Charles, while Goldware’s Grocery at 2302 North 27th Street was owned by an African American, too.

Wead’s Food Mart took over the Shavers store at North 25th and Ames Avenue in 1969. Later that year, a group of Black-owned grocery stores were bought and merged to be a Black-owned cooperative. The stores included Weads, the Larry Food Mart, F&L Grocery and Gate City Foods, and the co-op was called Good Neighbors Stores. However, the cooperative didn’t work and Weads closed permanently in 1970.

Black-Owned Funeral Homes

Funeral homes in Omaha were segregated throughout the city’s history. Seen as a steady middle class job, undertakers evolved from being self-taught to having apprentices into an academic degree. Several undertakers in Omaha began as apprentices with others, or as partners in a firm, but moved out on their own after a while. Of course, their businesses moved locations and closed, too.

For many years, the oldest African American-owned business in Nebraska was Myers Funeral Home, which operated for 90 years staring in 1921. Originally located at North 25th and Lake, they moved to 2415 North 22nd Street and stayed there for 75 years. Along with the Thomas Funeral Home at 3920 North 24th, which was founded in 1939, and several others, Black-owned funeral homes were vital to North Omaha for a century. The Jones and Chiles Funeral Home was located at 2314 North 24th Street in the Allen Building, which is still standing.

Black-Owned Entertainment

There have been many, many Black-owned entertainment businesses in Omaha history.

In the 1870s, conservatory-trained classical musician George T. McPherson opened the first Black-owned music studio in Omaha. For more than 25 years, he taught music to the “foremost white families” in Omaha. A local newspaper called him, “the leading pianist of the race.” Other early entrepreneurial African American musicians in Omaha included Lloyd Hunter (1910-1961) and Red Perkins (1890-1976) among others.

When she passed away in 1966, Florentine Frances Pinkston (1887-1966) was widely recognized as the most popular and longstanding music teachers in Omaha. After graduating from the New England Conservatory of Music in 1916, she started her 50-year-long career teaching at 2114 Lake Street. Mrs. Pinkston taught voice and piano after winning an award as an “outstanding director” from the New England Conservatory of Music. In addition to teaching more than a thousands students across six generations, she was honored by the Omaha Urban League and the Christ Child Society for her contributions to the community. A memorial was created after she passed called the Florentine Pinkston Scholarship Fund.

In the 1920s, the Workingman’s Club at North 24th and Burdette was owned by an African American businessman named Fred Jackson (18??-19??). The most famous Black-owned entertainment venue in Omaha history was James Jewell, Jr.’s iconic Dreamland Ballroom in the Jewell Building at 2221 North 24th Street. Jewell hosted the nation’s most famous performers. The Omaha Star owner Mildred Brown opened an alcohol-free, all ages venue called the Carnation Ballroom.

Others included Jim Bell’s Club Harlem, the Swingland Café, the Off Beat Super Club, Harlem Garden Club, Savoy Café, and the Cotton Club. Black-owned clubs like King Solomon’s Mines at North 25th and Ames, Paul Allen’s Showcase and Cleopatra’s at North 56th and Ames were important, too.

Many Black musicians in Omaha ran entertainment businesses under the premise of being a band. Without the management needed to support them, they operated as independent businesses sub-contracted out to dance halls and other venues across the region and received little recognition for their Black entrepreneurship. Some of these businesspeople included Nat Towles (1907-1962) and Dan Desdunes (1870-1929), among others.

In 1969, Darryl Eure (b. 1950), Howard Duncan and Dwight Beck opened the Afro Academy of Dramatic Arts at 2401 Ames Avenue. Focused on teaching and production, the academy ran through 1985. A Black-owned theater, there hasn’t been another in the city since it closed.

The city’s first Black-owned radio station was KOWH. Rodney Wead (b. 1935), the executive director of the nonprofit Wesley House, was responsible for its development and operation. From 1970 to 1979, Black DJs played music made by African Americans and broadcast from studios in North Omaha.

Black-Owned Bars and Taverns

Throughout Omaha’s 150+ year history, there have been many drinking establishments owned by African Americans. The most notorious one at the turn of the 20th century was called The Midway, and was located on Douglas Street downtown. It was owned by Jack Broomfield (1865-1927) ran it with his business partner Billy Crutchfield (1875-1917). The two were infamously tied up with Omaha’s crime boss Tom Dennison (1858-1934).

Less salacious was Mary Metoyer (1916-2008), who owned the M & M Lounge near North 24th and Lake Streets with her husband. Opened in the 1930s, M & M claimed to be Nebraska’s first Black-owned bar. It closed in 1983, and the spot was reopened as the Cornerstone Bar, which burned down in 1993. Andrew Strickland (c.1926-c.2004) bought the business in 1983, and ran it until 1991. An employee of his, Warren Brown, Sr., was a photographer who worked at the bar for 50 years when his sister Mary opened it. All 187 photos of customers he had taken from the prior decades that were hung there were lost during the fire. The entire block that housed this community institution and others was demolished in the early 2000s to make room for a new nonprofit facility.

The iconic Black-owned Stage II Lounge on North 30th Street was opened in the mid-1970s and just closed in 2019.

Black-Owned Hotels

Into the 1960s, white-owned hotels wouldn’t serve Black travelers, including entertainers, businessmen and families. The Green Book was a national travel guide used by African Americans to negotiate various racist practices and laws across the country, and Omaha had several entries including Black-owned hotels, boarding houses and travelers homes, with most in North Omaha. One Black-owned hotel was called the Broadview at 2060 Florence Boulevard, which stands still today. Another called Hotel Warden was owned by Henry Warden, and was open in the 1910s and 20s at North 16th and Cuming Streets. In the 1910s, an African American woman named Laura Cuerington owned the Washington Cafe and the Booker T. Washington Hotel at North 17th and Cuming Street, and it was in business for at least a decade. It was in the 1950s that John Walker opened his hotel at North 25th and Seward. After he passed away, his wife ran it until the early 1960s. The Lee Von Hotel was located at 2212 Seward Street, and offered rooms by the day or week. One of the most notorious Black-owned hotels in Omaha was by South 9th and Dodge Streets, and was called the Broomfield Hotel.

Black-Owned Pharmacies

Of the dozens of local drug stores that used to line North 24th, the most remarkable were Black-owned pharmacies that survived Jim Crow racism and fierce competition. One of these was Robins Drug Store, which was located at 2306 North 24th Street in 1936. Another was the shop of Williamson and Terrell, who were druggists at North 24th and Grant Streets. None survive today.

Black Professionals

Since African American professionals weren’t allowed to join the large institutions serving their city, most of the time they had to become sole proprietors, which white people didn’t have to do. Physicians, lawyers, dentists and others hung their shingles, ran their own billing and collected debts, established professional alliances and formed longtime practices in North Omaha.

Some of these professionals included Dr. Andrew Singleton (1895-1975), a dentist who operated at 24th and Lake. Dr. Singleton was elected to the Nebraska Legislature in 1926. A veterinarian, Dr. Bill Loft0n (1937-2015), ran an office at North 30th and Laurel Streets for almost 40 years.

Black-Owned Newspapers

Starting in the 1880s, Omaha has a long heritage of African American-owned newspapers. They included The Monitor, The Enterprise, the Afro-American Sentinel and several others. The longest-running is the Omaha Star, founded in 1938 by Mildred Brown, it was supported by local businesses and benefactors for more than 75 years. It is still running today as the outreach of a non-profit organization. The original Omaha Star offices are listed on the National Register of Historic Places today.

Black-Owned Banks

The Carver Savings and Loan Association, founded in 1944 by attorney Charles Davis, was the only African American-owned bank in Nebraska throughout its lifetime. Providing home loans, business loans and regular banking services for the community around 24th and Lake, the bank stayed open into the 1960s.

Working through the nonprofit he ran called Wesley House, community leader Dr. Rodney Wead worked with community partners to establish a new Black-owned bank for North Omaha called the Community Bank of Nebraska. The bank provided regular services, loans and more from its location on Ames Avenue at North 56th Street from 1971 until 1992. Wead was also responsible for several other Black-owned businesses in Omaha.

Black-Ownted Beauty and Hair Businesses

Youngblood’s Barber Shop at 4011 Ames Avenue is Black-owned, as well as the historic Goodwin’s Spencer Street Barber Shop. From 1955 onward, Goodwin’s has been court for civil rights and social change in Omaha, and the business is still going strong.

Starting in 1919 in Council Bluffs, the Althouse School of Beauty Culture was an accredited school provided licensed learning for students after 1,500 hours of classroom time. Founded by Christine Althouse (1895-1959), the institution was widely recognized for its expertise, and moved to its iconic location at North 24th and Pratt Streets in 1936. Mrs. Althouse wrote regular articles for the Omaha Star. “Madame Althouse,” as students referred to her as, was also the founder of Beauticians Local 101, and a national officer in the United Beauty School Organizers and Teachers Association. Starting with one chair, the school grew to eight instructors and a list of highly regarded Omaha beauticians as graduates. After his wife died, George Althouse (1896-1981) ran the school until he passed away in 1981. During that time, he was widely respected as the operator of the only Black-owned beauty school in Nebraska. This respect led him to be appointed to the Nebraska Legislature in 1970 when State Senator Edward Danner died before his term ended. In the 1980s, the school sponsored an Explorer post focused on cosmetology to teach young people about hair cutting, manicures and more. Eventually, the school was run by Larose Beasley and renamed the Larose Beauty Academy.

Black-Owned Retail Stores

Retail sales have been the heart of many Black-owned businesses in Omaha, whether they sell clothes, food, housing and decorations, or other goods.

For more than a decade starting in the early 1920s, the North Side Bazaar was located at 2114 North 24th Street. The story was a haberdashery, sold ladies clothes and notions, and was a “shirt hospital” offering a variety of tailoring services.

The Progress Store was opened by Jean Harris in 1970. Located on 16th Street just south of Dodge, it was a Black-owned variety store targeted to African Americans. In 1980, the Omaha World-Herald declared it was the first Black-owned business downtown, and a decade later it was “downtown’s only surviving Black-owned business.” The Progress Store was closed in 1987. In 1989, the Omaha Star shared an excited article about a “unique new Black-owned business” called The Jump The Broom. Owner Idonnia Kemp Lacy created the wedding coordination business to decorate weddings and events in the African tradition.

The first Black-owned bookstore in Omaha might have opened in 1971, when Lionel Hanspard opened the Harambee Book Store at 2416 Ames Avenue. With more than 1,500 books in stock, he also sold African jewelry, crafts and clothing. The store was a project of GOCA and was staffed by people under 25 years old.

Black-Owned Driving and Delivery

There were two main taxi services that served North Omaha, United and Ritz. Other taxis wouldn’t serve the community. However, there was another way to get around.

Jitneys are illegal taxicabs that have operated in Omaha since the 1910s. Jitneys filled a gap in Omaha for decades, especially in the African American community. With regular taxi drivers in Omaha being blatantly racist from the time cars were invented through modern times, they regularly drove past Black patrons who tried to hail a cab. Using their own cars, Black jitney drivers would pick up Black riders and take them throughout North Omaha.

There were several jitneys in North Omaha throughout the decades. In the 1920s, the City Messenger and Express Company was owned by Fred Davis at 2616 North 24th Street. From the 1960s on, the main jitney service in North Omaha belonged to LeRoy Bristol, Sr. (1928-1998), and was called Northside Delivery. Several popular drivers worked there, including an old guy called Stick ’em. According to the Proud to Be From North Omaha Facebook group, other services included Paul’s Place (also called 9688), Chappie’s Corner, Hill Top, Lake Street Delivery, Midway, and several others. In 1969, the Nebraska Railway Commission conducted an investigation into North Omaha’s jitneys, especially in the Near North Side. Rather than acknowledge the racism in Omaha’s taxis, they sought to “see how bad it is and what can be done to stop it.”

Jitneys keep running in the community today. From the 1980s through the 1990s, they were charging $3 to $5 per trip. Today they can cost up to $25 per trip. The increased popularity of ride sharing companies has taken away from jitney business and has mostly stopped the practice in North Omaha, but its still possible to get a ride from these Black-owned businesses.

Other Black-Owned Businesses

According to one study, by 1910 the number of Black-owned businesses had nearly doubled from 1890. These include shoemakers, hairdressers, laundries, tailors, an undertaker and a cigar store.

Alfred Grice (1923-2002) was one of the African Americans who integrated Omaha’s real estate industry. His agency served North Omaha in the 1960s and early 1970s, and in 1974 he become the executive director of the Mid-City Business and Professional Association, located in Grice’s real estate office at 3222 North 24th Street. The association sponsored seminars for Black businesspeople and focused on developing minority businesses in the city.

The Newson Construction Company was a Black-owned construction firm located at 4121 North 27th Street. Established and owned by Fred Newson, Jr. (1956-2002), the company was the largest Black-owned construction firm in Omaha in the 1970s, and in the 1980s employed more than 30 people.

Since African American business owners aren’t monolithic and Black consumers have choices, being a Black business in North Omaha has apparently never assured success or safety even. For instance, the Components Concept Corporation was a Black-owned business located on North 24th. Established in 1968 by Joe W. Saunders (b.19??), the Black-owned factory at 3815 North 24th Street developed computer parts for the government and private businesses. In 1970 their building was bombed. However, this appears to have been a set-up by the FBI to frame the Omaha Black Panthers. Regardless, the business struggled on and eventually left the city.

Before the 1960s, several billiard and pool rooms in North Omaha were owned by African Americans, too. Perhaps the most infamous Black-owned pool hall was the Idlewild Club at 24th and Lake, which was obliterated by the 1913 Easter Sunday tornado with several dead inside. Another included the Tuxedo Billiard Parlor at 2222 North 24th Street.

According to a 1994 edition of the Omaha Star, negro baseball was the second-largest Black-owned business in America. That may have been true in Omaha from 1947 to 1949, where the Omaha Rockets were an independent Black team with a Black owner named Will Calhoun (1908-1959). Calhoun also owned a hotel to house his team and others traveling through the city. Other Black baseball teams in Omaha included the Union Pacific Gold Coast Team in the 1920s and the Storz Brewery baseball team in the 1940s.

In 1990, a Black business expo was planned in conjunction with the NAACP Juneteenth celebration in North Omaha. “Black consumers need to know that many of the products and services they purchase can be obtained from a Black-owned business,” said one promotional flyer. “Dollars spent outside our community never return, they don’t create any jobs or wealth, it merely depletes our resources. Instead, if we can increase those resources, we’ll have a better chance of rebuildings our community in the 21st century.”

The Heart at 24th and Lake

For more than a century, the area around 24th and Lake Streets has been the center of African American entrepreneurship in Omaha. The Blue Lion Center may be the most visible sign of progress, and hosted many Black-owned businesses including the 34-year-long jazz bar Eugene McGill (1876-1960) ran called McGill’s Blue Room, as well as professional offices for real estate agents, African American doctors and dentists, and others.

In 1983, the Blue Lion Center became a featured symbol of business revival in North Omaha. The US federal Housing and Urban Development agency funded $1.4 million dollars in redevelopment with spaces for 10 shops and seven offices in the building. Another symbol of redevelopment during that era was the Hill Top Plaza, a commercial center at North 30th and Lake Streets. For that project, Ambrose Jackson Associates, the first African American-owned architectural firm in Omaha, redesigned the Blue Lion Center from two buildings at the intersection.

Today, the intersection of 24th and Lake is a hotbed of nonprofit services for the community surrounding it. The Union for Contemporary Arts has taken over the Blue Lion, renovating the space and adding artist housing behind it. Love’s Jazz and Art Center has been been there for 15 years, and the Family Housing Advisory Services opened a $3.3 million building in 2003. That building has played host to several Black-owned eateries throughout the years.

Today, many historic buildings including and surrounding this intersection is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places as the 24th and Lake Historic District, largely because of the its cultural significance including Black business ownership.

Black Ownership in Omaha Today

Many African American owned businesses call Omaha home today. For instance, Marshall Taylor opened the Aframerican Book Store in Omaha in 1989. Acting as a “community-based source for African American literature,” the store continues operating at 3226 Lake Street today.

However, in 2015 a study found that 3.2% of all Omaha businesses were Black-owned, with 7.65% of those having paid employees. The annual average revenue of those businesses was $65,000.

Another important development at the intersection is the Fair Deal Village MarketPlace at 2118 North 24th Street. Opened in 2017, the Fair Deal provides micro-retail opportunities in a dynamic environment owned by the Omaha Economic Development Corporation, or OEDC. Several Black-owned businesses are housed at the Fair Deal Village MarketPlace, and include the Fair Deal Grocery Market; Hand of Gold Beauty Room (nails, pedicures, makeup); Fashun Freak (women’s clothing and accessories); LikeNu Resale & Exchange (women’s clothing boutique); Mike’s Custom Creations (tennis shoe cleaning and customizing); Divine Nspirations (gift shop); 402Printz & Itz Poppin’ (printing services and gourmet popcorn); and Shadez of US (hair supplies); as well as Emery’s Cafe.

There are several organizations promoting Black business ownership and Black entrepreneurship in Omaha today. Some of them include Revive! Omaha Magazine, Empowerment Network, Omaha Small Business Network, The Start Center, Nebraska Enterprise Fund, Small Business Administration, Nebraska Business Development Center, City of Omaha Human Rights and Relations, Davis Companies, Greater Omaha Chamber of Commerce Thrive Program, Omaha Economic Development Corporation, Nebraska Black Business Association, Urban League of Nebraska and Catholic Charities Microloan Program.

Meanwhile, there have been events throughout the years to support Black businesses. For instance, in 2018 a group called Minorities About Business, or MAB, sponsored the Black Business Expo at the HOPE Center. Similarly, in 2019 they sponsored Black Business on the Blacktop, a vendor fair at the Bryant Center.

Special thanks to Malcolm Adams for his contribution to this article. Please send all additions, corrections and information to info@northomahahistory.com

You Might Like…

MY ARTICLES ABOUT SEGREGATION IN OMAHA:

Omaha Black-Owned Businesses | Segregated Schools | Segregated Hospitals | Segregated Hotels | Segregated Churches | Segregated Newspapers | Segregated Baseball

Historic Black Businesses and Businesspeople in Omaha

- History of the Omaha Rockets Independent Black Baseball Team

- History of the Carver Savings and Loan Association

- A History of the Calhoun Hotel

- A History of the Willis Hotel

- A History of The Omaha Guide

- A History of the Hillcrest Mansion in North Omaha

- A Biography of Helen Mahammitt

- A Biography of Rev. Dr. John Albert Williams

- History of the 24th Street Dairy Queen

- History of The Stage II Lounge

- A History of The Off Beat Club in North Omaha

- History of the Omaha Star

- A History of The Omaha Guide

Other Topics

- A Timeline of Race and Racism in Omaha

- A History of Segregated Schools in Omaha

- A History of Segregated Hospitals in Omaha

- A History of Black-Owned Hotels in North Omaha

- A History of Redlining in Omaha

- A Tour of Omaha’s Civil Rights Movement

- A History of Restaurants, Cafes, Ice Cream Shops and More in North Omaha

Elsewhere Online

- “Unity in the Community,” by Courtney K., Julianna C. and Jaylen F. for Omaha Public Schools Making Invisible Histories Visible project in 2011.

- “Industrial and business life of Negroes in Omaha” by James Harvey Kerns in 1932 for the University of Omaha.

- Private Sector Affirmative Action: Omaha by the Nebraska Advisory Committee of the United States Commission on Civil Rights in 1979.

- Time Out Foods official website

BONUS PICS!

Leave a comment