Emancipation Day was regularly celebrated in Omaha from 1891 to 1940. Juneteenth has been celebrated since 1977.

On January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which abolished slavery in the United States. Emancipation Day is a celebration of that action. With slaves among its residents, Omaha was among the cities in the region affected by this proclamation.

With no commemoration event in Omaha recognized by white-controlled media until 1891, it’s a wonder there was ever a newspaper article about Emancipation Day celebrations. However, there were, and they continue in some form today. This article is a history of Emancipation Day and Juneteenth in Omaha.

The End of Slavery in Omaha

Nebraska struggled to end slavery for a relatively long time after it became a territory in 1854. The first-known African American in Nebraska was a slave named York who belonged to William Clark of the Lewis and Clark expedition in 1804. In 1820, the Missouri Compromise made the lands that would become the Nebraska Territory slave-free. Then in 1854, the Kansas-Nebraska Act allowed the Nebraska Territorial Legislature to decide whether slavery to be legal in the Territory. It was effectively legal until 1862.

An 1855 census of the territory showed there were 13 slaves in Nebraska, and in 1860 the census found 10 slaves in the territory. While most were attributed to being held in Nebraska City, there. were several in Omaha. Local newspapers editorialized against emancipation, and a bill to ban slavery in the Omaha City Council in 1859 was soundly defeated.

As he’d done once before, in 1860 territorial governor Samuel Black vetoed a bill passed by the legislature to ban slavery. Recognized as a pro-slavery Southern Democrat, Black claimed the wording of the bill was ineffective. The New York Times took suit, sharing the precise language with the nation.

A year before President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, slavery was abolished in the Nebraska Territory. The early government, including the territorial legislature, the Omaha mayors; as well as other political and economic figures in the future state argued about slavery. Opposition to slavery didn’t always win out, either, as disenfranchising Black people effectively served as a barrier to statehood for Nebraska for several years. However, with the President’s intervention, the territory moved forward by abolishing slavery.

Even then after the Nebraska Territory prohibited slavery, legislators limited suffrage to “free white males.” This clause in the proposed 1866 Nebraska State Constitution delayed Nebraska’s entrance to the Union for nearly a year, until the legislature changed it.

After it was changed in 1867, Nebraska was admitted as a state in the Union, almost all formal vestiges of slavery were gone from Omaha. In 1875, the Nebraska State constitution was formally amended to ban slavery and involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for a crime. That provision once allowed convict leasing, a system that gave prisons the power to force former slaves back into unpaid labor for private parties.

“There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in this state, otherwise than for punishment of crime, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.”

Nebraska State Constitution, Article 1, Section 2 (1875)

It was another 16 years after that legislation, as well as 28 years after President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, before Omaha experienced its first publicly acknowledged celebration of the freedom of slaves.

The First Emancipation Day in Omaha

The first recorded instance of Black people in Omaha celebrating freedom was a Haiti Independence event held in July 1866. That year there was a festival to celebrate January 1, 1804, the day formerly enslaved Haitians celebrated their emancipation from French imperialists. Along with music and dancing, there was a large feast with “very select” attendence. Smith Coffee, one of Omaha’s first Black residents, was a manager of the event, and Professor Johnson’s String Band played at the events.

For several years before it happened in Omaha, there were announcements in the local newspapers about Emancipation Day events happening in other cities, including Cheyenne, Wyoming; Denver, Colorado; Washington, DC; and even Council Bluffs. All of these events were held on or around September 22nd.

In 1888, the Omaha Daily Herald was excited to announce that African Americans from Omaha were going to Council Bluffs to celebrate Emancipation Day there in honor of slaves’ freedom in the West Indies. Speeches, readings, orations, vocal and instrumental music, and a grand social were held that year. One article said the original Emancipation Day celebrations in the United States were held on August 1. That day was chosen because that’s when slaves were freed in the British West Indies in 1834, and free Blacks in the U. S. celebrated it even before their own freedom.

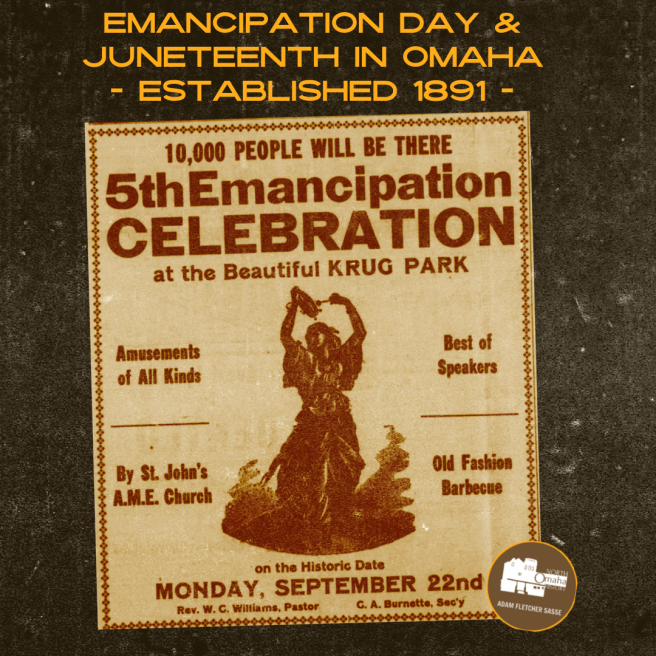

That might be why, if you can imagine, in September 1891 the newspaper was ecstatic to announce “the first time in Omaha it is celebrated right royally.” Sponsored by a social group called the “Cecilian Club,” African Americans gathered at Omaha’s Exposition Hall, also called the Grand Opera House, for a day of celebrations.

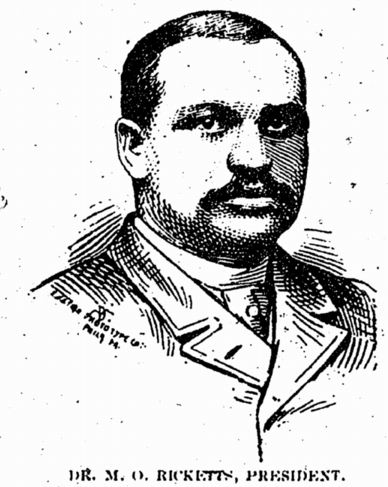

An African American pianist called Professor McPherson performed on a grand piano, with operas, comedies and other songs played. Miss Lenora Smith recited President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, and was followed by Dr. Matthew Ricketts, who spoke about the accomplishments of African Americans since Emancipation and explored the history of slavery in the United States. Miss Mattie Walker sang “Far From Me,” and Omaha’s first African American lawyer, Silas Robbins, spoke about the “general theme of the possibilities for the negro race and even encompassing it at present.”

After that, Prof. McPherson performed on the piano again, and then attorney D. L. Lapsley spoken on the history of Black people. A. L. Anderson sang the song “Abandoned, Wild and Free,” and Prof. McPherson performed again to close the celebration. The newspaper column wrapped up by announcing “Six white men with fiddles and other instruments useful and pleasant in their day and generation struck up dance music and the younger of the colored folks were a long way from being slow to take advantage thereof, and the dance went on.” There was a large meal afterward. The newspaper didn’t elaborate on how many people attended.

Less than a month later, on October 18, 1891, an African American worker named George Smith was lynched in downtown Omaha. There was no mention of an Emancipation Day celebration in the city in 1892.

Omaha Celebrations Continue

1893—A report said that Dr. Ricketts led the speeches at the 1893 Emancipation Day celebration at Fairmount Park in Council Bluffs. A concert and entertainment at the Masonic temple there were included in the festivities, and there were many people in attendance from Omaha. Another announcement came from Council Bluffs the next year, too.

1895—Dr. Ricketts and attorney Silas Robbins were speakers at this year’s Emancipation Day celebration held on August 1 at the fairgrounds, also called the Omaha Driving Park. Sponsored by the Afro-American Fair Association, the event was well-attended by the community. In addition to speaking, there was a 50-person choir, as well as horse races, bicycle races, foot races and baseball games.

1896—On August 4, the newspaper told about the Triumvirate Club, a group of African Americans in Omaha who “arranged for a grand excursion and picnic to be held at Chautauqua grounds” in Fremont in 1896. Led by Dr. Ricketts, an Hon. E. H. Hall and Fred L. Smith helped lead the day. The trip included a “hand concert” by Demick’s Seventh Ward Military Band, a performance by the Jubilee Choir, as well as swimming and boating. Sporting events included a baseball game between the Triumvirate Club and Fremont High School, with the school winning 11-1 in a five-inning game. There were one- and two-mile bicycle races, as well as and running races for men and women. In the evening there was a grand concert and reception at the Masonic Temple. The train left the Webster Street Depot at 8:15am. Later, the newspaper reported that a special train of six cars was filled to overflowing “with the colored people of the town.” They started arriving back around 10pm, with the last train leaving Fremont at 1am.

On September 22rd of the same year, Mount Pisgah Baptist Church hosted Emancipation Day events at Syndicate Park in South Omaha. Opening at 10am with prayer and music, A. T. Young read the Emancipation Proclamation, then Dr. Ricketts spoke to the crowd. Lunch was followed by an organized debate between attorney Silas Robbins and Rev. G. W. Woodbey versus attorneys E. H. Hall and F. L. Smith. There was no mention of the topic of the debate. “The attendance at the park was quite satisfactory,” reported the paper without any numbers. In 1897, another celebration happened at the same park with “addresses, music, games, and basket lunch.”

1899—The Prince Hall Masons planned an excursion train for an Emancipation Day picnic in Fremont on July 10, 1899. Holding 250 passengers from Omaha, there were estimates of another 250 joining “from other directions.”

There were several years without any mention of Emancipation Day in the newspaper.

1901—In September, there was a short blurb in the Omaha World-Herald about an Emancipation Day celebration in Council Bluffs. Featuring Rev. J. W. Cluke from Omaha’s Mount Pisgah Baptist Church, there were also addresses by judges and ministers from Council Bluffs. About 100 people attended. In 1902, special excursion trains from Omaha took revelers to Nebraska City for celebrations “in due and approved style.” There were several bands, good speakers, a balloon ascension and competitions. Other trains came from Lincoln and Atchison, Kansas, and was marked to “be the biggest celebration ever attempted by the colored people of this state.” According to the paper, bout 50 people attended from Omaha.

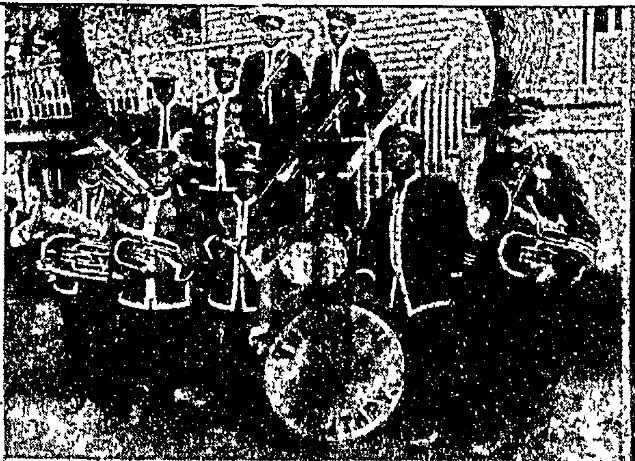

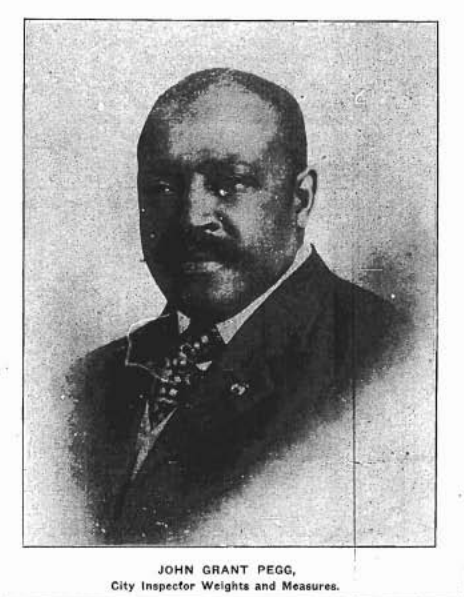

1906—A grand parade finally was reported in Omaha again in September 1906. With 500 onlookers, African Americans marched from Jefferson Square to 15th and Howard Streets with the Omaha Military Band, which was made of African American musicians. Streetcars then took revelers to Hibbler’s Park, a private facility at 44th and Leavenworth Street. Rev. J. A. Bingaman of Zion Baptist Church was the master of ceremonies, with J. F. Bruce as the parade marshal. Mayor James Dahlman delivered the opening speech, and Rev. G. W. Wright of Mount Moriah, Silas Robbins, Fred L. Smith and John G. Pegg gave other speeches. Big meals were served to about 500 people at the park, and speaking was done around 5pm. After a large BBQ dinner was served, the Omaha Music Union Band played starting at 9pm. The event was so important the newspaper wrote a feature on it, including several photos and a large, bold banner.

1907 & 1908—A celebration was held in December 1907 in Council Bluffs, and in 1908, an African American social club called the People’s Mutual Interest Club held a celebration at Riverview Park for about 300 people. A dinner was served, and the women played a game of baseball. Formal speeches were given by Pinkett, who presided over the gathering and read the Emancipation Proclamation. W. J. Johnson spoke, and North Omaha’s architect Clarence Wigington followed him with a brief speech.

1909—The World-Herald declared “today is the Fourth of July for the colored race in America,” and there was another large celebration in September, 1909. The city’s auditorium was the scene for “several hundred” African Americans and “a small scattering of white people.” They listened to US Senators E. J. Burkett and Norris Brown, along with Mayor Dahlman, A. W. Jeffers, and Dr. Ricketts, who came back from his new home in Missouri. The Dan Desdunes Band played, and attorney Harrison J. Pinkett was the master of ceremonies. Mrs. Othello Roundtree led the North Omaha Women’s Club in providing lunches for the participants, and a 50-person choir opened the festivities. Pinkett led the event, with invocations led by Rev. Wright from Mount Moriah. Mayor Dahlman’s speech eulogized Abraham Lincoln, whose face was featured above the stage in a large oil painting. Senator Brown read the Emancipation Proclamation, and declared there was “no race problem.” Senator Burkett lectured the crowd and demanded they “do something; accomplish something… Times are as good as when your father was a boy.” Dr. Ricketts wouldn’t stand for that though, and during his speech he said,

“You have the race problem right here in Omaha… and you will always have it as long as there is discrimination between the races. You will have it as long as privileges are extended to a white woman, no matter what her morals may be, when you deny the same to the brightest, best educated and most cultured women of the negro race.

I declare that the same opportunities are not open to the individuals of my race. We are barred from them because of the prejudice of the white man. We do not contend for social equality, but we do contend for civil dignity and civil rights.”

—Dr. Matthew O. Ricketts, as quoted in “Emancipation Day duly celebrated” in the Omaha World-Herald, September 23, 1909.

After the speeches, the Mutual Interest Club and the Desdunes Amusement Company performed for a ball with 300 attendees. The paper said it “was one of the most brilliant affairs of the kind ever held in the city.” The program was printed on fine, heavy paper with Abraham Lincoln embossed on one side and American flags slathered across the other.

The Omaha Bee reveled in a controversy affecting the 1909 celebrations. They gleefully announced in a front page article that several North Omaha ministers were resentful about being named as supporters of the Emancipation Day dance that year. Rev. W. S. Dyett of St. John’s AME and Rev. John Albert Williams of St. Phillips Episcopal Church were listed among 25 others as members of the organizing committee, when apparently they had never agreed to participate. Apparently, the AME was highly opposed to dancing and couldn’t support the Grand Ball that evening. The two ministers were seen walking around the community pasting over their names on posters advertising the events.

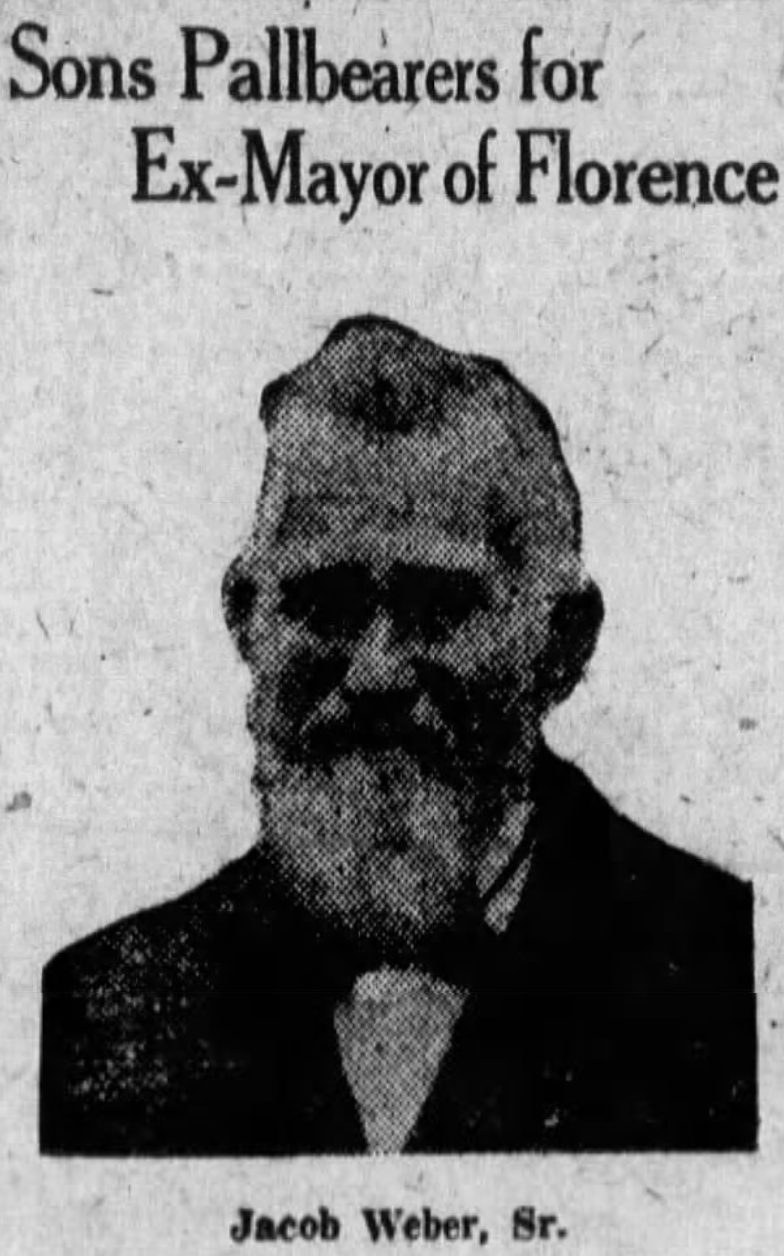

1910 & 1911—Hibbler’s Park hosted a smaller-sounding gathering in 1910, and then in 1911 there was another large celebration. That year crowds gathered at the Golden Sheaf Park, a small private park at North 24th and Patrick Streets that was bought in 1910 by the Golden Sheaf Tabernacle. Led by acting mayor Louis Berka, others joined including Judge Ben S. Baker, Vic Rosewater, John L. Kennedy, and John Grant Pegg. The newspaper reported the audience was made of mostly women, since the event happened in the middle of the afternoon when men were working. After the politicians left, a large BBQ fundraiser was held that raised $127 to help Golden Sheaf Tabernacle pay off the cost of the park.

1913—The Knights and Daughters of Tabor hosted Emancipation Day celebrations in Omaha on September 22nd, 1913. The African American social organization held speeches, a big BBQ and other activities at North 24th and Patrick Street. The featured speaker was Frank Walker, a 100-year-old former slave. Also speaking were Judge Lee S. Estelle, James B. Wootan, John Grant Pegg and Mayor Dahlman. African American students were released from school that afternoon to attend the event.

Then, there were no reports of Emancipation Day in Omaha until 1921. The time period between 1914 and 1921 in Omaha history included the reign of crime boss Tom Dennison; World War I and the migration of many African American workers to Omaha; and the lynching of Will Brown.

1921—The governor of Nebraska, Samuel R. McKelvie, spoke at the 1921 Emancipation Day celebrations in Krug Park. St. John’s AME Church hosted the event, with a parade, Dan Desdunes Band, sports events and a BBQ on the program. According to the Omaha Bee, the event was used as a fundraiser to raise money for St. John’s new $100,000 church building. The World-Herald reported that,

“…many employers of negroes let them have the day off as a holiday.”

—From “Negroes celebrate Emancipation Day” in the Omaha World-Herald, September 13, 1921.

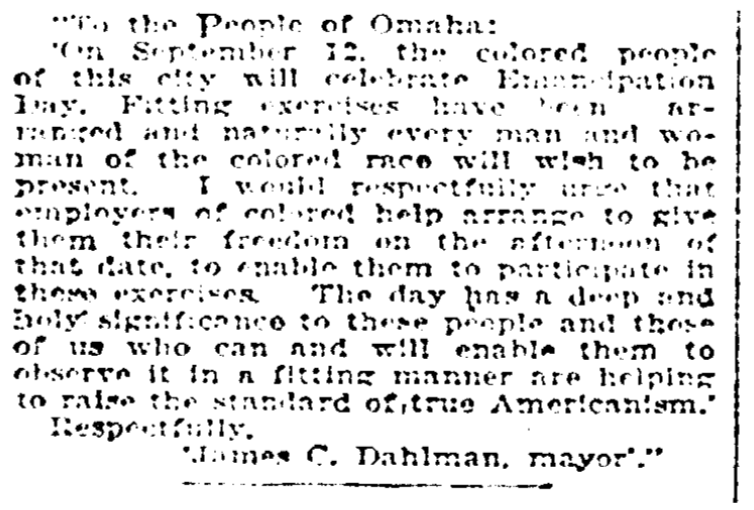

Then in September 1922, Mayor Dahlman signed a proclamation urging Omaha employers to give their African American employees half of the day off on Emancipation Day.

“To the Citizens of Omaha: The colored people of our city have made arrangements for the proper observance of Emancipation day, September 11th. The day will be given over to picnicking and athletic events at Krug park, and it is the one day in the year when these people from every part of the city are given an opportunity to hold a genuine reunion, and enter into the spirit of appreciation they feel for this act of the great Lincoln. It is highly creditable to them that they have, year after year, made this single demonstration of their gratitude, and I respectfully suggest that wherever possible, their employers allow them their freedom for this day. Respectfully, JAMES C. DAHLMAN, Mayor.”

1923, 1924 & 1925—Governor Bryan spoke at a large Krug Park gathering in 1923. A parade downtown was following by a BBQ, sports events and the governor’s speech. The next year in 1924, 1,400 people joined in the events that began at St. John’s AME Church and went to Krug Park, then included speakers, a BBQ, dancing and the crowning of three queens. In 1925, there were 1,500 people gathered at Krug Park for Emancipation Day celebrations. They were led by attorney and Rev. John Adams, Sr. of St. John’s AME, who spoke about emancipation and the end of slavery. The chairman of the events was James A. Clarke, and the event was sponsored by St. John’s AME. Beforehand, a parade including the U. K. T. Band and several floats went through downtown Omaha. A similar program happened in 1926, including the parade and the crowning of the queen. For the first time, the write-up mentioned old-timers talking about past Emancipation Day celebrations in Omaha.

1927—This year featured several articles in the Omaha World-Herald that practically begged of Omahans to let African Americans leave work to celebrate Emancipation Day. Mentioning a big picnic, speaking and athletic events, the mayor of Chicago was scheduled to speak, too. The Krug Park events included an African Methodist Episcopal Bishop, a sermon by Omaha’s Rev. John Adams, a basket picnic, Dan Desdunes Band, and a 150-person choir.

In September 1928, a Black-owned newspaper in Omaha called The Monitor editorialized,

“It is quite right that Emancipation Day should be fittingly observed. That our people were once enslaved is nothing to be ashamed of. There have been several others, Anglo-Saxon, Greek and Roman, none excepted. It should be regarded as a community affair. For several years now a date in September has been selected for its observance in this city. It was inaugurated and conducted primarily as a commercial enterprise of the benefit of one institution. This brought just criticism. This year a sincere effort by a committee to make it a community affair. This committee invited the cooperation of all classes and organizations. They did not get it; but they tried to do so, and this is to their credit. They have moved in the right direction. September 11 is the day set for the Emancipation Day celebration and we sincerely hope that it may be a decided success, pointing the way to larger and better observance in the coming years.

—From “Emancipation Day,” in The Monitor, September 7, 1928

“Dirty 30s” Celebrations

1931—6,000 people were expected to attend the 1931 Emancipation Day events at Krug Park. A 50 car parade led people to the park. Speeches were given that day by Omaha Mayor Metcalf and others. Prizes for events were sponsored by St. John’s AME, and included a loving cup, a ton of coal, sacks of flour and several hams.

1932—The 70th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation was celebrated in September 1932 at the city auditorium. The mayor spoke again, along with Dr. John Singleton and H. L. Anderson. Dr. Wesley Jones was the master of ceremonies. The St. John’s AME choir performed, along with the Desdunes Band.

1933—On January 12, 1933, the Omaha Urban League produced an Emancipation Day program for KOIL radio.

1934—A Krug Park program was mentioned in the paper in September 1934, but no details were provided. After that, there was no mention of Emancipation Day for several years. In 1938, radical change happened.

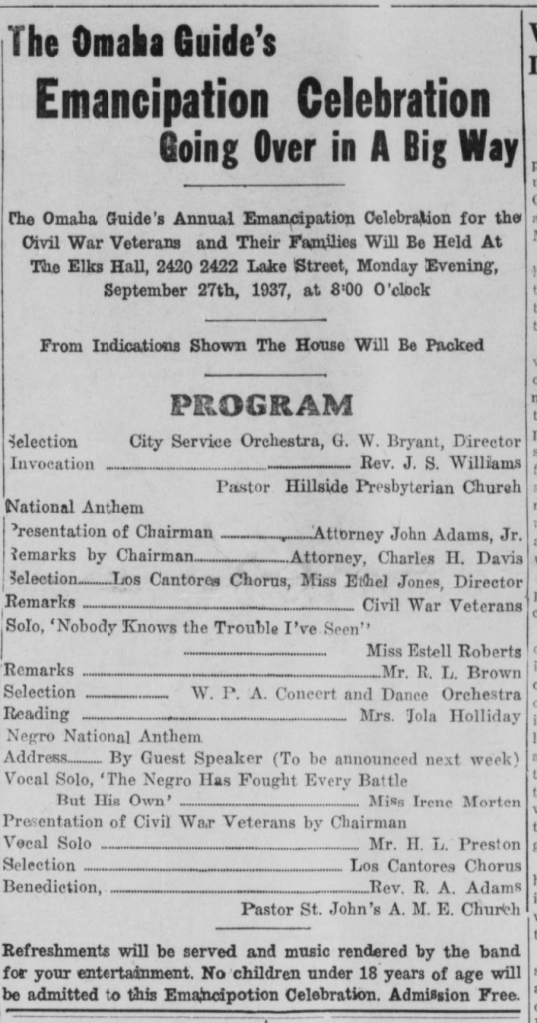

1937—Throughout the 1930s, the Omaha Guide, a Black-owned newspaper, sponsored an Emancipation Day celebration. Their celebrations were held at the Elks Hall, and featured music, speeches, readings, vocal performances, and prayers.

The New Afro-American Day

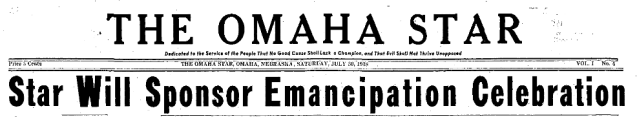

1938—Inviting African Americans from across the Midwest to attend a gathering at Omaha’s Krug Park on September 10, 1938, a new Black newspaper called the Omaha Star was an ambitious sponsor of that year’s Emancipation Day celebrations. A new event ostensibly to advertise the new paper, it was rebranded as “Afro-American Day,” the newspaper anticipated 20,000 participants and suggested civic organizations, clubs, fraternities, civic groups, churches and others promote the event and take part. A massive parade made of dozens of entries was planned with a police escort leading it, followed by massive activities at Krug Park. There were rides, a swing contest featuring two bands, prominent speakers, and prizes awaiting attendees. There was also free ice cream and free admittance to the park. Attendance was high, speakers were vivacious, and free ice cream was enjoyed by hundreds of children at the gathering.

1940—The Star apparently continued sponsoring gatherings for the next few years. In 1940, the newspaper sponsored a gala day with band music, ball games, speeches and free ice cream at Fontenelle Park. African Americans from surrounding Midwestern cities were invited, and there was an evening event at the pavilion. Two African American officers with the Omaha Police Department led the parade that year, and were followed by representatives of the American Legion Roosevelt Post #30, and were followed by the “Negro Fire Department Company.” The Works Progress Administration, or WPA, Band played, and dozens of other organizations joined. There was also an Afro-American Day ball that evening, along with speeches, a performance by a large choir, and a performance by the WPA Band from 8:30 to 11:30.

However, at some point the celebrations stopped. In September 1943, there was a letter to the editor of the Omaha World-Herald that remorsed,

“Wednesday was Emancipation Day and 99 out of one hundred never knew it, or that we used to have big parades and meetings with speeches on this day.”

—From “Town Tattler” in the Omaha World-Herald, September 23, 1943

Starting in September 1947, there were a number of advertisements in the Omaha Star celebrating the emancipation of African Americans from slavery.

In September 1953, the World-Herald reported on Emancipation Day at the Iowa State Penitentiary. “They start planning about two months in advance,” the warden reported. “They organize their own committees, usually headed by… a lifer, and make all their own plans.” There was no comment or report on any event in Omaha though. A similar article appeared in the September 27, 1957 edition of the Omaha Star.

On January 1, 1959, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. scheduled a Pilgrimage of Prayer for Public Schools nationwide to celebrate Emancipation Day that day. Fueling “massive resistance” nationwide, the Omaha Star featured the action and promoted joint action. As a “day of prayer and sacrifice for the sufferings of all oppressed people,” King called on ministers to move forward. Although they were direct in their reporting, the Star didn’t report on much of what happened in Omaha. The newspaper did report that Corinth Baptist Church had an Emancipation Day service on that day, including reading the Emancipation Proclamation.

In 1962, the newspaper reported that the US Congress was taking up a resolution to designate September 22, 1962, as Emancipation Proclamation centennial day. There was no report on how Omaha or its representatives responded, and the legislation didn’t pass. That November, the NAACP Youth Council sponsored a meeting at the Near North YMCA to plan a celebration of the 100th anniversary of Emancipation Proclamation the next year. There were no mentions of activities in the papers for several years after that article.

1968—In the late 1960s, Emancipation Day came back into the spotlight in Omaha. With the longstanding Civil Rights movement, the previous summer’s rioting on North 24th Street, and the growing Black Power movement, the Omaha NAACP selected January 1, 1968 as the right timing for Omaha’s Emancipation Day celebrations. Musical performanced by the Salem Baptist Church Youth Choir, Mt. Calvary Community Choir and the Bethel Baptist Choir were scheduled, and Rev. J. C. Wade of Salem was designated as the master of ceremonies.

1975—Dr. J. Andrew Thompson was the pastor at Corinth Memorial Baptist Church when they held an Emancipation Day service on January 1, 1975. Guest choirs and speakers from several Baptist congregations joined them, including Mt. Nebo and Pilgrim.

The Great Plains Black History Museum sponsored a research trip with five carloads of participants to attend the Hutchinson, Kansas Emancipation Proclamation Day celebration in August 1978. Researchers attended rodeos, interviewed participants, and a disco dance. They also went to a parade attended by white and Black people, as well as a community picnic with 1,000 attendees.

Becoming Juneteenth in Omaha

Emancipation Day has evolved throughout the years, and today is known as Juneteenth, Emancipation Celebration, Freedom Day, and Jun-Jun. The day marks two important dates:

- The first is June 19, 1862, when Congress prohibited slavery in all current and future United States territories (though not in the states), and President Lincoln quickly signed the legislation the same day.

- The second was the announcement of the end of slavery in Texas that happened on June 19, 1865, two years after the Emancipation Proclamation.

Juneteenth celebrates the emancipation of enslaved African Americans, and is recognized as a state holiday or special day of observance in forty-five states.

1977-1984—The first celebration of Juneteenth in Omaha happened in 1977. The Woodson Center—originally established as the Omaha Negro Cultural Center—celebrated the seventh annual Juneteenth Emancipation Day Picnic on June 17, 1984 at Woodson Park at 3014 Jefferson Street. Entertainment and prizes were provided for the potluck, which was held from noon to 6pm. Dr. Rodney S. Wead of the United Methodist Community Centers was the main speaker for the event.

“It is not enough to simply involved Black people and other oppressed minorities into the structures of existing society as those systems continue to press… We are all missionaries committed to standing with the poor inspired by the Holy Spirit.”

—Dr. Rodney S. Wead, as quoted in the Omaha Star, June 28, 1984.

1987—The Omaha Star announced that a “Juneteenth Committee” received broad support across from across the community in 1987. The city’s police, fire and parks departments joined the parade, along with churches, businesses, the Salem Stepping Saints, American Legion Post #30, Cookie’s Pride Drill Team, Shriners and others. Governor Kay Orr and Mayor Bernie Simon issued proclamations in support of the Juneteenth Emancipation Celebration Week, with sponsorships from the Urban League of Nebraska and the Charles Crew Health Center. Around this time North Omaha’s American Legion Post #30 became a regular sponsor of the event.

1989—The Omaha NAACP chapter has sponsored the city’s Emancipation Day celebrations since 1989. That year, it was held at Corinth Memorial Baptist Church on January 12. With the goal of focusing its attention on the NAACP and the status of Black people, there was a forum and Q&A session. They did the same again in 1993.

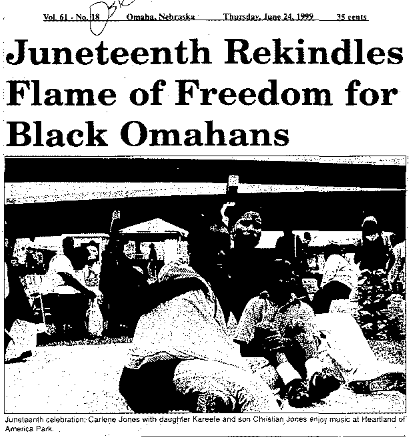

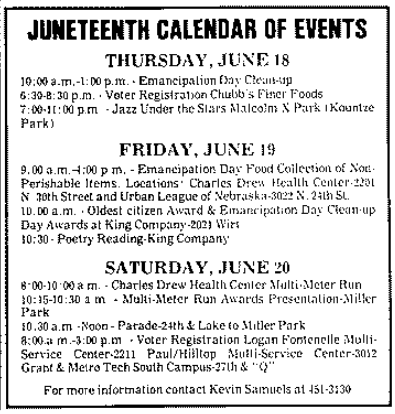

1999—The tenth NAACP Juneteenth celebration in Omaha happened in June 1999. With events at the Heartland of America Park downtown following a parade, Councilman Frank Brown was the Grand Marshall of the events. The Negro National Anthem was sang by Celeste Webster, and guitarist Grover Lipkins performed the Star Spangled Banner. There were also performances by West African dancers, gospel groups, the Sons of Thunder, Echoes of Melody, Ges Werk, Rhythm City, and Decision. Know Thyself Production also performed an Egyptian play.

2008—In 2008, the Charles B. Washington Branch Library hosted a Juneteenth celebration called the June Family Fair, including live music, a puppet play, a petting zoo, face painting and clowns, moonwalks, carnival rides, live music and more. Book displays featured Black history, and families were encouraged to bring lawn chairs and enjoy the evening. The Dixon Family Foundation supported the event, and Friends of the Omaha Public Library sponsored it too.

2009—The Juneteenth flag was raised at the Charles B. Washington Branch Library on June 12, 2009. Several important community members attended, and Rev. Frederick McCullough of St. John’s AME gave a prayer. There was a week of activities planned, including church services, a national prayer breakfast, and a parade. The NAACP named Rudy Smith as the Grand Marshall of the Juneteenth Parade that year, celebrating his lifelong service in the Civil Rights movement as a photographer and more.

In the last decade, the Nebraska State Legislature passed resolutions supporting celebrating Juneteenth statewide. In the last several years, several organizations throughout North Omaha have sponsored and participated in Juneteenth celebrations, including the Great Plains Black History Museum; the Malcolm X Memorial Foundation; the Charles B. Washington Branch Omaha Public Library; the Sidedoor Lounge; Carver Bank; St. John’s AME Church; the Elks Club; and others. There have also been parades, NAACP Juneteenth Community BBQs, a family fair and more.

2015—The Charles B. Washington Branch Library has continued hosting their Juneteenth celebration called the June Family Fair, with another in 2015. It featured music, bounce houses, face painting, snacks and more. It was free and ran from 1 to 4:30 p.m.

As this article shows, there have been Emancipation Day celebrations in Omaha since at least 1891. There are several unanswered questions though:

- The earliest Emancipation Day celebrations were held in Washington, DC in 1864. Why did it take almost 30 years for the first celebration to happen in Omaha?

- Why were early celebrations held in Council Bluffs and not Omaha? Iowa was a more racially progressive state than Nebraska; were there explicit threats to gathering in Omaha? Or was it about the size of the cities and their African American populations: Council Bluffs was on parity with Omaha for several years; were the celebrations there out of sheer size?

- Why was Mayor Dahlman apparently so supportive of Emancipation Day? He was a known stooge in the pocket of Tom Dennison; were his politics purely corruption? Was his support of Black people purely self-serving?

- What happened in the interceding years when there weren’t reports of Emancipation Day celebrations in Omaha? Did the gatherings happen and go unreported? Were they suspended intentionally or coincidentally?

As Omaha’s African American community continues evolving today, respecting and learning from Omaha’s Black history is essential for white people. Its also important to understand how history affects today, including the history of slavery in Omaha. For instance, its important we know that due to the work of North Omaha’s Senator Justin Wayne, in 2020 Nebraska voters will get the chance to stop allowing people to become slaves as punishment for crimes. Slavery still isn’t illegal in Nebraska!

Today, there is no plaque, historical marker or other commemoration marking Emancipation Day, Juneteenth or the Emancipation Proclamation in Omaha.

You Might Like…

- A Tour of the Civil Rights Movement in Omaha

- A History of African American Firsts in Omaha

- A Timeline of Racism in Omaha

MY ARTICLES ABOUT THE HISTORY OF MUSIC IN NORTH OMAHA

PEOPLE: George T. McPherson | Dan Desdunes | Flora Pinkston | Jimmy Jewell, Sr. and Jimmy Jewell, Jr. | Jim Bell | Paul Allen, Sr. | Josiah “P.J.” Waddle | Frank “Red” Perkins | George Bryant

PLACES: 24th and Lake Historic District | Dreamland Ballroom | Carnation Ballroom | Stage II Lounge | Club Harlem | The Off Beat Club | King Solomon’s Mines | Allen’s Showcase | Druid Hall

EVENTS: Stone Soul Picnic | Emancipation Day & Juneteenth | Native Omahans Festival

Elsewhere Online

- NAACP Juneteenth Parade Celebration in Omaha Facebook page

- “National observance of Juneteenth is still a struggle,” by Jacqueline J. Holness for UrbanFaith.com

- “Slavery in Nebraska” by Edson P. Rich for the Nebraska State Historical Society in 1887

- “Legislative Resolution 351,” 102nd Nebraska State Legislature in 2011

- “Modern Slavery in Omaha” by Dezi LaPierre, Kelly Alonzo, Chyla Floyd for the Omaha Social Project

- “Celebrating Juneteenth: local and national contexts” by Adam Ortega, Kietryn Zychal, Myles Davis, Emily Chen-Newton and Lyndsay Dunn for NOISE

BONUS PICS!

Leave a comment