There has been a LOT of music in North Omaha over the last 150 years, including jazz, soul, blues, hip hop, gospel, pop, and so much more. To try and summarize it is ridiculous; however, in order to preserve and promote the community’s musical history I am going to introduce some of this heritage. To write this article, I have researched the Omaha World-Herald, the Omaha Star, the Omaha Guide, and several other periodicals; I have read autobiographies by several musicians; I have watched several interviews with legacy musicians; and I have combed details from several other primary and secondary sources. Despite all that, the information included here is woefully incomplete. This is a history of music in North Omaha.

If you have more information, knowledge, or ideas let me know in the comments section please.

Who Does Music Belong To?

Before diving into the specifics of North Omaha’s musical heritage, let explain this: Music belongs to the heart that feels it.

That might sound cheesy, but I want to acknowledge that there is music that as a white person, I just can’t understand; as a dad, there is music I don’t want my young child to hear. But as a singer, there is music I want to try and sing; as a historian, there is music I want to share. Whether it is jazz, soul, blues, hip hop, gospel, pop, punk, metal, a cappella, do-wop, or any of the other plethora kinds of music that has been played, made, loved or just listened to, North Omaha has a deep musical heritage that needs to be acknowledged.

Of course, there has always been music in North Omaha. Before Europeans arrived, Native American tribes had music for recreation, religion, courting, and more. European migrants came with orchestral music and folk songs, religious music and more. African Americans enriched North Omaha’s musicianship, and today music continues. There have been important places for music, people affecting music, and musical events in the community for at least 170-plus years.

The music of North Omaha belongs to people who feel it, make it, appreciate it, collect it, or learn it. I hope I do any of it justice in this article, and if I don’t, if I miss things, or otherwise fail this goal, I hope you’ll share your thoughts in the comments section.

Discrimination in North Omaha’s Music Scene

From the earliest years, there was plenty of white supremacy at work in Omaha’s music scene. During the Great Migration from 1910 to 1920, Omaha’s Black population doubled from almost 5,000 to 10,315, boosting musicianship, innovation, and the stature of music in North Omaha. Its well-documented that African American entertainers were allowed to play to white audiences; however, when it came to places to stay, places to eat, or people to socialize with, Black performers weren’t allowed to be around white people or use white spaces. Black entertainers were kept from drinking from the same bars as white people. These Jim Crow practices lasted into the 1970s, and there is still an understanding in Omaha right now that Black musicians can’t perform in certain spaces throughout the city.

Local white-owned businesses made a lot money off African American bands early on. For instance, the National Orchestra Service was an important company based in Omaha that managed Black and integrated territorial jazz bands. These bands traveled around the Midwest to entertain white people by playing in halls, ballrooms, clubs, and other spaces. They rarely played for Black audiences, often skipping over African American towns to continue on main highways to the larger whites-only venues. The owners of this company made a lot of money, often leaving musicians with little play for their hard labor. Despite Black entrepreneurs owning labels and running booking firms today, the practice of white businesspeople making money off the work of Black entertainers in Omaha continues today.

In the 1930s, the federal government decided to invest in North Omaha’s music scene. They did this because music belongs to everyone. The Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) “Negro Orchestra” played the Dreamland Ballroom during the Great Depression, and Omaha musicians were employed by other projects as part of the Works Progress Administration, too. However, investment doesn’t equate to justice; African Americans were disproportionately affected by the Great Depression, and for every dollar put into music industry people in North Omaha several were extracted in return by white music fans who consumed the music scene without staying in the area for other entertainment, lodging, meals, or other expenditures. This is to say that while music belongs to everyone, it doesn’t affect everyone the same.

Omaha’s Black Musicians Before Jazz

Some of the earliest successes for Black musicians in Omaha were from the Black community in Omaha.

In 1895, Black leaders put together an Emancipation Day celebration on August 1, sponsored by the Afro-American Fair Association. A well-attended event, it featured a 50-person choir, as well speakers, horse races, bicycle races, foot races and baseball games. The next year, in 1896, a newspaper reported told about the Triumvirate Club, a group of African Americans in Omaha who “arranged for a grand excursion and picnic to be held at Chautauqua grounds” in Fremont in 1896. Led by Dr. Ricketts, an Hon. E. H. Hall and Fred L. Smith helped lead the day. The trip featured a “hand concert” by Demick’s Seventh Ward Military Band, and a performance by a group called the Jubilee Choir. On Emancipation Day in 1909, the Omaha World-Herald declared “today is the Fourth of July for the colored race in America.” The city’s auditorium was the scene for “several hundred” African Americans and “a small scattering of white people” who listened to the Dan Desdunes Band and a 50-person choir throughout the festivities. A 150-person choir was featured at the 1927 Emancipation Day celebration.

Throughout the earliest era of North Omaha’s history, vaudeville was a major source of music in the community. Performances by instrumentalists, singers, singing troupes, and bands were major draws for those acts, and a variety of Black musicians and others came from North Omaha. Many of those people are lost to history though.

During the silent movie era (c1890-1914) there were many music performers from North Omaha. They played in the first North Omaha theaters, including the Alhambra Theater, the Franklin Theater, and others.

Featured Performer: Professor McPherson

“…the leading pianist of the [African-American] race”

The Enterprise, February 13, 1897

The early 1870s saw the arrival of George T. McPherson (1864-1916) in Omaha. Later declared “the leading pianist of the [African-American] race” by a Black newspaper in the city, he had graduated from several music conservatories in the East and Europe. Addressed as “Professor McPherson” in the media, McPherson was the first prominent black musician in Omaha. He lived in Florence in an era when it was restricted to whites only. McPherson was a musical prodigy and virtuoso multi-instrumentalist who ran a music studio for the young students from the wealthiest white families in Omaha, as well as African American students. By 1916, McPherson was committed to the Ingleside Hospital (shown here) for the Insane in Hastings, Nebraska, where he continued performing. Presumably he was there until his death. Read “A Biography of George T. McPherson” »

Featured Place: Pinkston School of Music

“Nebraska’s foremost Negro teacher of piano and voice.”

Federal Writers’ Project on Flora Pinkston

Flora Pinkston (1887-1966) was widely recognized as the most popular and longstanding music teacher in Omaha. After graduating from the New England Conservatory of Music in 1916 and studying at the Paris Conservatoire with Isador Philipp through 1922, she started a 60-plus year career as a private music teacher. Mrs. Pinkston taught voice and piano, theory and harmony. Today, her family home still stands at 2415 North 22nd Street. Read “A Biography of Flora Pinkston” »

Featured Leader: Josiah Waddle

Born into slavery in Springfield, Missouri, “Professor” Josiah “PJ” Waddle (1849-1939) was a U.S. Army veteran who moved to Omaha in 1880, when he was 31 years old. During the Civil War, Waddle was a drummer in the 79th Kansas Colored Infantry Regiment. A barber by profession, he kept a shop on the northeast corner of North 26th and Lake Streets. He and his first wife had two children, Emma (1878-1882) and Gertrude (1880-1882). The first African American musical group in the city was established by Waddles as a 15-piece band and orchestra. In 1925, he formed the Waddle’s Ladies Concert Band and for the next decade they played around Omaha. That band was an all-women’s band made up 18 to 22-year-old women who were the descendants of Civil War vets and former slaves. According to Omaha historian Ryan Roenfeld, Waddle was called “Professor” because during the ragtime era of the early 20th century, Waddles was a master pianist who could play better than anyone. After living at 2411 Lake Street for a long time, Waddle and his second wife, Belle (1874-1952), moved to 2807 North 24th Street around 1911. He was there when he died in 1939 at the age of 90. Read “A Biography of Josiah Waddle” »

Featured Advocate: Dan Desdunes

For more than 20 years, Dan Desdunes (1870-1929) was the foremost African American musician, bandleader, and music advocate in Omaha. Not only did he lead his own band and teach generations of students, he also worked hand-in-hand with Father Flanagan to lead the Boys Town Orchestra and Marching Band. As a fundraiser, his influence and leadership brought thousands of dollars into Boys Town’s operations from across the country as the Boys Town Band traveled nationwide. Representing music interests in Omaha, he brought necessary attention to the youth at Boys Town and made music education obtainable for generations who wouldn’t have access otherwise. Read “A Biography of Dan Desdunes” »

Gospel Choirs

Omaha’s historic African American churches have a long history of religious music including gospel and traditional songs. More recently, a number of churches throughout the community have become nationally and internationally famous for their music in a number of formats.

The Goodwill Spring Musical was an interdenominational extravaganza held annually from 1934 until 1946. Founder Luther McVay, a Pullman porter and member of St. John A.M.E., saw as the purpose of the musicals “the bringing about of a closer relationship between the churches, the choirs, and the encouragement of the use of musical talents, the realization of which greatly adds to the value and dignity of the church.”

From the 1930s through the 1950s, perhaps because of the influence of the Goodwill Spring Musical, church choirs were featured heavily in Omaha’s Emancipation Day celebrations for the community. In 1968, the city’s re-emergent Emancipation Day celebration featured several choirs, with performances by the Salem Baptist Church Youth Choir, Mt. Calvary Community Church Choir, the Corinth Memorial Baptist Church Choir, and the Bethel Baptist Church Choir.

During the 1930s, the Black Methodist congregations of North Omaha celebrated the Union Services, which were multi-congregational gatherings at each others’ churches in order to pray, worship, and sing together. The choirs of St. John’s A.M.E., Bethel A.M.E., Cleaves Temple C.M.E., and Clare M.E. Church to celebrate Union Services.

The Church of God in Christ has been particularly influential in maintaining and growing Omaha’s gospel movement. Other influential nondenominational choirs have had varying amounts of influence over the years, too.

There have been other great breakthroughs in Omaha’s gospel choirs, too. One of the driving forces in Omaha gospel have been the church choir directors, including those who have been conductors and music writers, too. In the 1940s, Thelma S. Polk was one of them, leading choirs for the Church of God in Christ and teaching students gospel from her studio at North 24th and Erskine Street.

All That North Omaha Jazz

North Omaha used to be a hub for black jazz musicians, ‘the triple-A league’ where national bands would go to find a player to fill out their ensemble.

–Preston Love, Sr. in A Thousand Honey Creeks: My Life in Music from Basie to Motown―and Beyond (1997)

Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, The Nat King Cole Trio and Lionel Hampton are just a few of the eminent jazz performers to play North Omaha. With the influence of crime boss Tom Dennison and his lieutenants in the community, for the first 30 years of the 20th century North Omaha had a “loose” entertainment environment where live music was played, dancing was had, and a lot of good times were had by the people who came to be entertained.

Big name entertainers and others came through Omaha all the time, and North Omaha was the premier place for African American musicians to whet their chops while they traveled the country.The King Cole Trio lit up the area, playing at the Dreamland to huge crowds wearing zuit suits and doing the jitterbug. According to Richie Love, band leader Johnny Otis, the Godfather of Rhythm and Blues, became friends with Preston Love, Sr. when he started playing in Omaha in the early 1940s. Later he was responsible for bringing a number of future heavyweights to the city, including Little Esther Phillips, Etta James, Big Mama Thornton, Johnny Ace and many others.

A number of elders in the community today remember the North 24th and Lake Historic District as being hot spots for jazz when they were young in the 1940s. Music drifted from open windows and back doors of popular places where local and national players would jam, play their sets, and rally through dance music and more for large groups of Black and white people. Crowds spilled onto the streets and there are many stories about racial co-mingling, swelling numbers, and raucous loud good times being had by all.

The early history of African American musicians in Nebraska generally followed national trends. George McPherson, the first popular Black musician in Omaha, arrived in 1871. The first Black bands emerged playing military marches, and included Demick’s Seventh Ward Military Band, the Tenth Cavalry Band, the Omaha Military Band, and Lewis’ Excelsior Brass Band. Marching bands that transitioned from military marches to jazz between the turn of the century and the 1920s included the Dan Desdunes Band and others led by Josiah Waddle.

Early North Omaha jazz bands included Simon Harrold’s Melody Boys, the Sam Turner Orchestra, the Ted Adams Orchestra, and the Omaha Night Owls, as well as Red Perkins and His Original Dixie Ramblers. Nat Towles Orchestra was a renowned territory jazz band based in North Omaha, too.

Red Perkins and his Dixie Ramblers was an early popular band in North Omaha. From 1920-22 he was with a quartet in an Omaha cabaret, while doubling as a brass band during the daytime. The Melody Five was his first group, with his Dixie Ramblers forming as a sextet when Perkins took over the Night Owls in 1923. Until 1925 the group played local engagements and toured surrounding states. In 1931, Red Perkins and His Original Dixie Ramblers became the first Omaha band to record their music, including “Hard Times Stomp” and “Old Man Blues.” From 1936 on the Original Dixie Ramblers had a large 14-piece big band set up, and the band kept touring the Midwest. From 1925 through the 1930s, Professor Josiah “P.J.” Waddle kept Omaha’s first-ever all-women’s band called the Waddle’s Ladies Concert Band.

A jazz band called Lloyd Hunter’s Serenaders was the first Omaha band to record in 1931, and a later version of this act called Lloyd Hunter Orchestra was home to the first performances by a young saxophonist named Preston Love, Sr.

By the 1920s, there was a lot of competition among bands in the Midwest, and in the 1930s Lloyd Hunter’s Serenaders was a most respected band than Red Perkin’s Dixie Ramblers.

Jeri Southern (1926-1991) was an example of the diversity of North Omaha’s jazz scene. After graduating from vocal lessons and other classes at the Notre Dame Academy and studying piano and voice at Duchesne Academy, she went on to become a major jazz singer and pianist.

Anna Mae Winburn made musical history as one of the earliest and most famous leaders of an all-women’s band called the International Sweethearts of Rhythm. She started at 24th and Lake as the leader of the Cotton Club Boys, which included the amazing guitarist Charlie Christian. Winburn traveled the local region as a typical territorial band. However, upon the advice of North Omaha impresario Jimmy Jewell Jr., owner of the Jewell Building, Winburn left Omaha and hit the “big time” with the IInternational Sweethearts of Rhythm. There were several notable Omaha musicians in Winburn’s band, including trombonist Helen Woods Jones.

Featured Performer: Preston Love, Sr.

Preston Love, Sr. (1921-2004) was one of Omaha’s most long-standing and impactful musicians. A band leader for half of his life, Love got his break with the Count Basie Orchestra, playing with them from 1944 to 1947. Playing on Basie’s only #1 Billboard song, “Open the Door, Richard,” Love played with many of other major stars of the swing era, too.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Preston Love, Sr. was the leader of the Motown West Coast band. Playing with the greatest bands of the era, including the Supremes, Temptations, Four Tops, and more, his contributions to the vibrant Detroit sound being played nationwide were outstanding.

In 1997, Love published A Thousand Honey Creeks Later: My Life in Music from Basie to Motown―and Beyond. The book has proved to be a powerful personal account of North Omaha’s jazz scene from an insider who grew up in it. Love details the story of North Omaha’s music culture from the 1920s through the 1940s before serving up his long career as a towering giant of the community and the national jazz culture.

Later in his life, Preston came back to North Omaha. Working for the Omaha Star, he also wrote for the Omaha World-Herald about the city’s jazz history. One of his daughters, Portia Love, is a longtime vocalist, while his other daughter, Laura Love, is a singer, songwriter and bass player. His son, Preston Love, Jr., is a longtime politician and activist.

According to Leo Adam Biga, from 1971 until early 1996 Love hosted several radio programs devoted to jazz. Will Perry, the general manager of KIOS, described Love’s on-air saying,

“He was fearless. He was not afraid to give his opinion, especially about what he felt was the inequality black musicians have endured in Omaha, and how black music has been taken over by white promoters and artists. Some listeners got really angry.”

— Will Perry, the general manager of KIOS (2010)

Preston Love, Sr. died in 2004.

Created after his passing, the Love’s Jazz and Arts was opened at 24th and Lake to celebrate the African American culture of North Omaha. It closed in 2019.

Singing the Blues

In 1923, Black musicians and siblings Effie Tyus and Charles Tyus wrote the music and lyrics for a vocal duet called “Omaha Blues.” The story of a man who wants to get back to his hometown, the narrator dreams of returning to Omaha to settle down near his parents back at home. He goes on about his love back in Omaha describing her as, “just as sweet as any peach from a tree”. He’s going to get back to the city no matter what, even if he has to walk.

Before he became one of the founders of rock-and-roll, Wynonie Harris (1915-1969) was a resident in the Logan Fontenelle Housing Projects. He got his start as a dancer in Jim Bell’s Club Harlem, and in the 1930s he gained a reputation as a blues shouter around the community. While he later moved to LA, his success serves as an essential marker for the health of the early blues in North Omaha.

Big Joe Williams was one of the premier blue players who covered “Omaha Blues,” playing his signature style repeatedly from the 1950s through the 1970s.

In the early 2000s, Preston Love, Sr., remarked of the current trends being played, “We must treat this new blues as a bastardization, a mutation. Why treat it as an art form? It’s a commercial idiom to make some bucks.” While he didn’t care for modern blues music, he loves historic blues and was a lion in North Omaha’s rich blues tradition. Unfortunately, today that tradition has been diminished by the few blues players and committed locations for playing the music throughout the community.

Rock and Pop in North Omaha

North Omaha has been home to a lot of different types of music, including polka and classical, pop and hip hop.

In the 1940s, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, an inventor of the Rock-and-Roll genre, came through the community all the time with her signature swagger and style alive on North 24th Street. Omaha-born Wynonie Harris, another one of the founders of rock and roll, lived in the Logan Fontenelle Housing Projects and got his start at the North Omaha clubs. The influential rock drummer Buddy Miles was friends with a lot of different musicians while he grew up in the “Little Vietnam,” as Logan Fontenelle was known from the 1960s onward. Funk band leader Lester Abrams is also from North Omaha. Lalomie (Lomie) Washburn was a songwriter and backup singer for Chaka Khan, Stevie Wonder and Aretha Franklin.

For nine years starting in 1970, North Omaha was home to the city’s first Black radio station, KOWH. Owned by, operated by, and targeting African American listeners, KOWH played soul, gospel, pop, and rock music by national and local African American singers and bands. The radio personalities there were mostly local and featured many people who continued being important in the community’s music scene long after the station closed in 1979.

Many popular North Omaha nightclubs rose and fell on pop music, including King Solomon’s Mines at 24th and Ames, Cleopatra’s at 60th and Ames, and Richter 9.9 in the old Ames Plaza.

Hip Hop and Today

In the 1980s, North Omaha had a burgeoning hip hop scene featuring breakdancing, graffiti, rapping, and more. Houston Alexander, a.k.a. Scrib or FAS/ONE, led the Scribble Crew as an alliance of graffiti artists. A performance group he led was called the Midwest Alliance, and was active from the 1990s and into the new millennium. The Young Rebels was a group with a semi-major record deal, and Suavey Spy and his local DJ Disco Rick operated from Bellevue. For several years, Alexander was a DJ on an Omaha radio station hosting an independent music show featuring hip hop, and he facilitated an elementary school program that taught students about hip hop called the “Culture Shock School Tour”.

In 2009, North Omaha native Marcey Yates aka Op2mus, a rapper and producer, established the Raleigh Science Project as a music and arts collective. Focused on growth, development, artist branding and community event planning, the collective includes Omaha rappers Mars Black, Mark Patrick and Xoboi. In 2016 The Raleigh Science Project held it first annual music and arts festival ” The New Generation Music Festival.” Yates has been quoted saying that the Omaha hip hop scene didn’t start until 2014, when he and others became active.

North Omaha Music Places & Spaces

There are SO MANY places related to the music of North Omaha that it would be impossible to name them all. Some were more popular and impactful than others, and others have made more money. A few of the most popular music places and spaces in North Omaha include the the 24th and Lake Historic District with venues like McGill’s Blue Room, Allan’s Showcase, and the Dreamland Ballroom. Cleopatra’s was near North 60th and Ames, and hosted modern music for more than two decades. In the 1970s there were clubs in the former Ames Plaza and in the old North Star Theater, including the popular King Solomon’s Mines. Mildred Brown ran her popular all-ages venue called the Carnation Ballroom at North 24th and Miami for a decade, hosting some of the biggest rising stars in rock and blues.

Since it was constructed in 1914, the Druid Hall has hosted a lot of music. Given the number of parades and special events on North 24th, North 30th, and several other streets throughout the community, streets have long musical histories that should be mentioned here. And there are spaces that are gone from history, too, like the old clubs that were at 2410 Lake Street, 20th and Lake, and other places throughout the community.

North Omaha’s churches have always been musical places. Fantastic classical and gospel choirs, illustrious conductors, and interdenominational performances and competitions have highlighted the depth of the community’s religious musicianship while elevating the cultural aspirations of many congregations. Churches throughout the area have also played host to performances by many musical stars, too, with religious performances by recording artists, radio stars, and others.

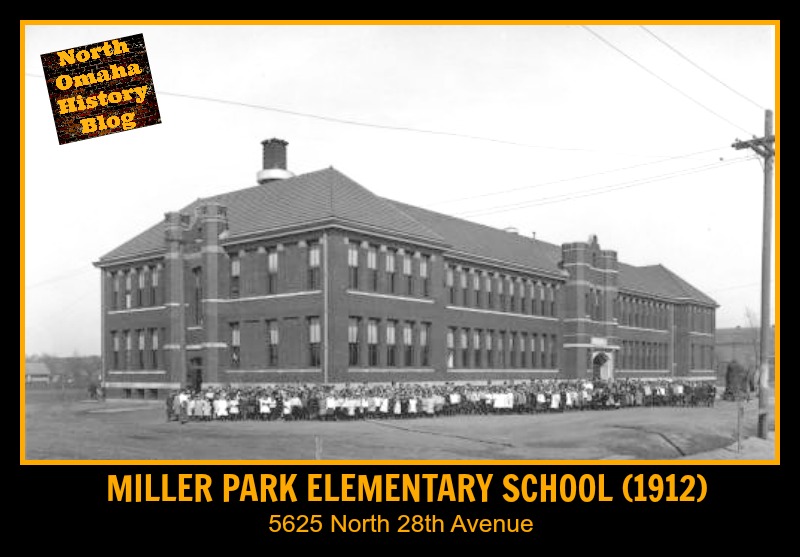

The community’s high schools, including North High, Tech High, and Central High, each have had roles in fostering North Omaha’s musical legacy. Throughout its illustrious history, the auditorium at Tech High has hosted dozens of performances by Black musicians in the era of Omaha’s strict informal Jim Crow. Disallowed from attending high brow performances in downtown’s fancy show palaces, a century ago African Americans enjoyed attending opera, classical, and other performances by major stars from the times at Tech High.

Countless bars, clubs, and other nightspots have been important music venues, too. Some of the hottest spots in the community’s history have included Cleopatra’s on Ames; Dreamland Ballroom on North 24th; King Solomon’s Mines on Ames; Allen’s Showcase on Lake; Carnation Ballroom on North 24th; Stage II Lounge on North 30th, and McGill’s Blue Room on North 24th. Some addresses were more vital to the history of the community’s music than others, like 2406 Lake Street, which played host to Jim Bell’s Club Harlem and the Off Beat Club, as well as a half-dozen other businesses that catered to Omaha’s music tastes, too. Today Johnny T’s Bar and Blues at North 30th and Spaulding is the main place to see the blues played live in North Omaha. There have been many, many other nightspots in North Omaha throughout the last 140 years, too.

There are countless other places and spaces that are important to the history of music in North Omaha. Some of the peripheral places included the Black hotels and rest homes throughout the community. In Omaha’s segregated climate, many African American performers weren’t allowed to stay in the mainstream hotels and motels throughout the city. To respond to that need, places opened throughout North Omaha to serve Black guests. Musicians and their managers heard about these informal stays through their networks, and the popular Green Book.

In the five decades after the riots of the 1960s, many nonprofit organizations have played host to music programs and efforts for African Americans and other young people throughout the community. Perhaps the most popular was the Wesley House United Methodist Community Center, which provided educational opportunities, scholarships, and even a radio station for the community. Many others had music education programs, too.

The Stone Soul Picnic started at Carter Lake in 1971 and ran for more than 30 years. Organized by the Near North YMCA, the Wesley House and the KOWH radio station, it was sponsored by the Omaha Star, Coca-Cola Bottling, Larry’s Food Station, and other businesses in North Omaha and beyond. The picnic featured all kinds of music, including stepping bands, jazz, blues, rock, hip hop, and more.

Another annual event in North Omaha is called the Omaha Blues, Jazz, and Gospel Festival. It has been held for almost 20 years as a benefit concert for the North Omaha Foundation at Fort Omaha starting in the early 2000s. The event featured local, national, and international performers including Lady Mac and Preston Love, Sr.

A number of parades have happened and continue to happen throughout North Omaha that include music or feature bands, including the Native Omaha Days Festival parade and the North High Homecoming parade.

A community center for North Omaha culture-building activities and the arts, the Culxr House has operated on North 24th Street since 2019. A spectacular institution filled with vigor and power, the Culxr House offers weekly open mics, music showcases, and other activities. They also provide creatives with space and materials to grow their craft.

The Past and The Future

Today, there are a few homages to North Omaha’s musical history. They include the Dreamland Plaza, which was opened by the City of Omaha in 2003 as a tribute to North Omaha’s jazz history. Located at North 24th and Erskine Streets, its a park covering a single lot, the area is a well-groomed plaza. The featured element in the park is a 9 foot tall statue called “Jazz Trio.” Created in 2005 by nationally recognized sculptor Littleton Alston, it features a jazz trio with a trumpeter, sax player and female singer performing. The plaza is named for the Dreamland Ballroom.

North Omaha native musician Vaughn Chatman started the Omaha Black Music Hall of Fame in 2005 to highlight contributions by African Americans to classical, rhythm & blues, big band, jazz and gospel music. Over the course of several ceremonies almost 100 people have been recognized. Some of the performers recognized include band leader and saxophonist Preston Love, Sr. (1924-2004), singer Wynonie Harris (1915-1969), band leader and trumpeter Lloyd Hunter (1910-1961), trombonist Helen Jones Woods (1923-2020), drummer Lester Abrams (1945-), jazz guitarist Calvin Keys (1943-), guitarist Lois “Lady Mac” McMorris, drummer Buddy Miles (1947-2008), percussionist Luigi Waites (1927-2010), and singer Lomie Washburn (1941-2004).

In 2022, an organization called NOMA, or North Omaha Music and Arts, is opening a new academy to teach youth in the community about the arts. According to their website, “Our vision is to enrich the community by becoming a destination for master class Music and Art education and a venue that attracts renowned talent.” Located in the former Love’s Jazz and Art space at North 24th and Lake Streets, NOMA appears to be the future forefront of music and art education in North Omaha.

Share your knowledge, memories, and other reflections about music in North Omaha in the comments section!

Special thanks to Ryan Roenfeld for his contributions to my research on this article.

Musicians from North Omaha

- Lester Abrams (1945-), band leader

- Ted Adams, band leader

- Houston Alexander, DJ

- Dan Desdunes, band leader

- Simon Harold, band leader

- Wynonie Harris (1915-1969), band leader, singer

- “Lady Mac” Lois McMorris, guitarist, singer

- Lloyd Hunter (1910-1961), band leader

- Stemziel “Stemsy” Hunter, saxophonist, signer

- Orville Johnson, pianist

- Calvin Keys (1943-), guitarist

- John Lewis, band leader

- Terry Lewis (1956-), producer and songwriter

- Preston Love, Sr. (1924-2004), saxophonist, band leader

- Portia Love, singer

- George McPherson (1864-1916), pianist, teacher

- Buddy Miles (1947-2008), drummer

- Flora Pinkston (1887-1966), pianist, teacher

- Red Perkins, band leader

- Herbie Rich, keyboardist, saxophonist

- Jeri Southern (1926-1991), pianist, singer

- Criss Starr, multi-instrumentalist

- Nat Towles, band leader

- Sam Turner, band leader

- Steve Turre (1948-), trombonist

- Josiah “P.J.” Waddle (1849-1939), band leader, teacher

- Luigi Waites (1927-2010), percussionist

- Lomie Washburn (1941-2004), singer

- Anna Mae Winburn (1913-1999), band leader

- Helen Jones Woods (1923-2020), trombonist

- Marcey Yates, rapper, producer

You Might Like…

MY ARTICLES ABOUT THE HISTORY OF MUSIC IN NORTH OMAHA

PEOPLE: George T. McPherson | Dan Desdunes | Flora Pinkston | Jimmy Jewell, Sr. and Jimmy Jewell, Jr. | Jim Bell | Paul Allen, Sr. | Josiah “P.J.” Waddle | Frank “Red” Perkins | George Bryant

PLACES: 24th and Lake Historic District | Dreamland Ballroom | Carnation Ballroom | Stage II Lounge | Club Harlem | The Off Beat Club | King Solomon’s Mines | Allen’s Showcase | Druid Hall

EVENTS: Stone Soul Picnic | Emancipation Day & Juneteenth | Native Omahans Festival

Sources

- NOMA (North Omaha Music and Arts) official website

- “The Black Church in Omaha” by Leo Adam Biga for NOISE in July 2021

- Tom Jack. (1992) Gospel Music in Omaha, Nebraska: A History. University of Wisconsin-Madison.

- Gospel Music Omaha website

- “Preston Love Sr. (Tribute)” by Richie Love

- “Culture Shock School Tour“, Houston Alexander

- “Music Festivals return to North Omaha” by KMTV (June 4, 2021)

- “Omaha’s Hottest Rappers Of 2020!” by Rap Omaha

- “North Omaha: The Triple A of Jazz” by Brittney C., Trent H., Cora S., Jennifer Moyer, and Brandon Locke from Making Invisible History Visible, a project of Omaha Public Schools

- “Damned Your Eyes” cover of Etta James by Cynthia Taylor and the All-Blues Band at Love’s Jazz and Arts Center in 2013

- “Preston Love: His voice will not be stilled” by Leo Adam Biga (2010)

- “For the Love of the Music Omaha’s Jazz History,” Making Invisible Histories Visible, Omaha Public Schools (2020)

- “Omaha Blues Sheet Music” (1924) from the History Harvest.

BONUS PICS!

Leave a comment