After an early history filled with American Indian hunting grounds, fur trading posts, fleeing religious groups, and people living Gophertown and other places around North Omaha, the community’s history kept growing.

North Omaha grew in little towns; it grew in isolated ethnic neighborhoods; and it grew around churches and schools. The reasons it grew varied, but always depended on the people who were growing it.

This is a middle history of North Omaha covering the era between the 1870s and 1950s. A lot happened in those 80s years, and I tried to give each topic covered here an introduction, but not much more. I hope its useful!

Neighborhoods

Where the early history of North Omaha was made of rugged settlers and town builders, the middle history is about community building, struggling, and ambitious businessmen. While downtown Omaha was growing in strides from the 1860s through the 1880s, North Omaha became an area filled with countryside estates for wealthy people and hovels for poor folks. Through this period it eventually fills in, and whites start to move out.

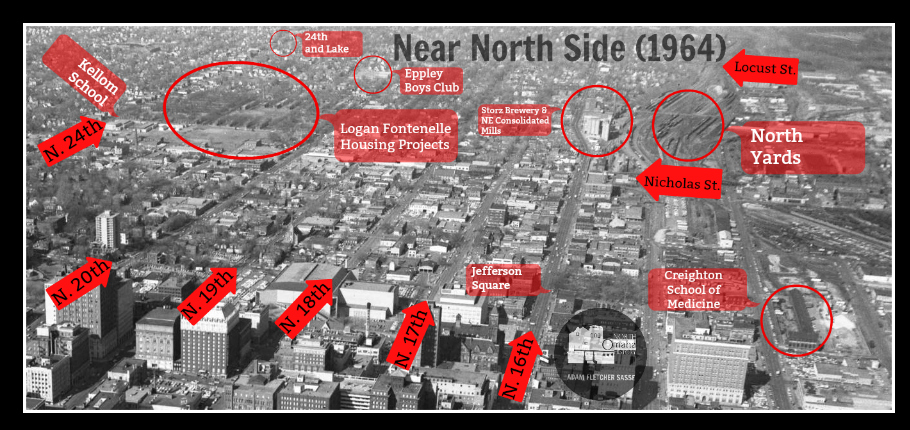

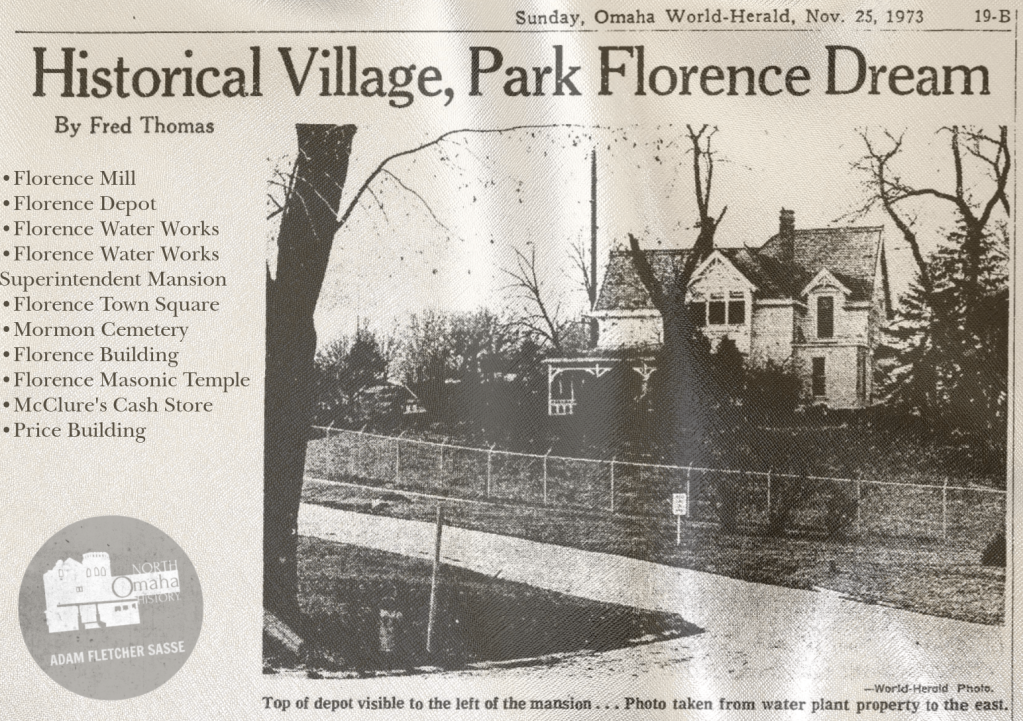

Some of the earliest neighborhoods in North Omaha include the Near North Side and Walnut Hill. The pioneer towns of Florence, East Omaha and Saratoga (including Sulphur Springs) continued growing at their own paces. North 16th was called Sherman Avenue and only had country estates on it, and North 24th was called Saunders Street. North 30th wasn’t hobbled together until 1900, and Cuming Street was the only east-west main street.

Early Neighbors

In early Omaha history, North 16th Street (called Sherman Avenue for a while) was the main northbound road out of Omaha, heading north to Florence. Cuming Street headed west, and split to the northwest to take riders to Fremont. the Winter Quarters Road continued north to Blair. Several wealthy Omahans built their estates in present-day North Omaha, including A.J. Poppleton, Herman Kountze, former Territorial Governor Alvin Saunders, and John Reddick.

The Redick Mansion was built at 3612 North 24th Street, at the edge of Herman Kountze’s platted claim, in 1875. The Redick Mansion would later play an important role in the development of North Omaha, and eventually the city as a whole.

Other towns popped up around the area during this time, including DeBolt, Middleville, and Briggs.

50 Years of Growth

The rest of modern-day North Omaha developed moderately. The Near North Side, closest to downtown, developed quickly in this middle period by providing moderate-sized homes, apartments and flats for working class European immigrants and African Americans.

During that same period, from the 1870s through the 1880s, a small neighborhood of African American families developed nearby and was called “Portertown”; eventually, the African American population of Omaha came to reside throughout much of the North Omaha area. By the 1910s, the size of the African American community threatened whites so much that the neighborhood was redlined, effectively forcing African Americans to stay alienated and isolated in a specific area.

East Omaha became an enclave of low income whites, including the area around the old Florence Lake and Lake Nakoma, now known as Carter Lake, once known as Cutoff Lake. The lake was a hotbed of local sporting in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and featured sailing events, rowing clubs, Bungalow City, and the Omaha Gun Club.

In the next 50 years, European ethnic groups in the area included Jewish people from Russian, Latvia, Lithuania and other eastern European countries; Scandanavians, including Norwegians and Swedes; Germans; and English people, whose distinct architectural styles can still be seen around Saratoga. Eventually, the neighborhoods around the town of Florence, including Minne Lusa, Miller Park and Belvedere all sprang up.

The Florence Boulevard developed spectacularly, first as “The Most Beautiful Mile in America”, and later as a suburban driving road with wonderful views of the river. Starting with the development of the Minne Lusa neighborhood, in the 1910s the area near Florence became home to a Danish immigrant community. With a variety of churches and social clubs, the neighborhood was the cultural center for many of North Omaha’s working class and middle-class whites. Neighborhoods grew around the old Prospect Hill Cemetery, showing up as Orchard Hill, Prospect Hill and other areas. Benson became popular, had a trolly and other features, including the once amusement park at Krug Park. The neighborhood surrounding Fontenelle Park filled in nicely, weaving along the once recreational drive of Fontenelle Boulevard. But the most important neighborhood in North Omaha during this period was easily Kountze Place. Platted by pioneer Omaha banker Herman Kountze, this neighborhood became a wealthy suburb built for doctors, lawyers and other white collar business owners. Before opulent houses and spectacular churches were built there, though, Kountze had to attract buyers. To do that, he donated land to a group of business leaders who were launching a grand event to promote the city.

Businesses

Early businesses and housing were propelled by the introduction of a horse-driven street railroad in the 1870s, and electrical streetcar lines operated in North Omaha until 1955. There were lines throughout the city, and depots across North Omaha. They included the Weber Street Station, the Oak Chatham Depot, the Lake Street Station, the Druid Hill Station, and the Walnut Hill Station. Benson and Florence had depots, too. Streetcars were very important to the development of the community.

Some early businesses in North Omaha were established by Jewish immigrants, who became part of the larger community of successful business people who built downtown Omaha.

African Americans established a strong business district in the area of 24th and Lake Streets in the 1920s, including clothing, barbers, butchers, tailors, morticians and recreational businesses.

There were more than twenty movie theaters in the history of North Omaha. Some examples include the Minne Lusa Theater, a one-screen neighborhood movie house that opened in the mid-1920s; the Diamond, the Corby, the Lothrop, the Beacon, the Loyal, the Ritz, and the North Star Theatre.

Lincoln Motion Pictures was America’s first Black-owned movie production company, located right in North Omaha. The Lincoln company was a minor success that moved to Los Angeles and produced several “race films” over its 5 year run. The McFarlan Moving Picture Company was also a Black-owned movie production company in North Omaha.

There were also pool halls, social halls, bowling alleys, bars and dancehalls throughout the neighborhood.

Driving for Fun

In 1875, the Omaha Driving Park Association bought land between Laird and Boyd Streets, and 16th to 20th Streets for horse racing, specifically, trotters. Commercial Avenue lined the park from 16th to 24th Street.

A fair association leased it, added some features, and held the Douglas County Fair and the Nebraska State Fair there for many years. But that park got boring, and by 1899 it was mostly ignored. Later, the land was platted and houses were built after WWII. Some of the businesses started while the park was still there still exist today, including J.F. Bloom and Company, started in 1879 to build monuments.

North Omaha’s Beers

Several beers have been made in North Omaha, including the city of Omaha’s biggest. The Storz Brewery was one of the major employers in North Omaha. Located along 16th Avenue and Clark Street, it was finished in 1894 and stayed open into the 1970s. The Storz Brewery was 600 feet tall and had a capacity of 150,000 barrels a year, making it one of the largest breweries in the region. The entire facility occupied more than 15 buildings with red-tiled floors and walls, burnished stainless steel and copper fixtures.

Other Businesses

North Omaha had its fair share of roceries, bakeries, meat, poultry and fish markets, clothing, drug, hardware and shoe stores and more. There were also hucksters, peddlers, and salesmen. North Omaha’s immigrant communities in North Omaha also worked in packing houses, smelters, junkyards and on the railroads.

From the 1920s through the 1950s, Reed’s Ice Cream Company operated 63 small “ice cream bungalows” that distributed their ice cream across Omaha, including more than a dozen stands in North Omaha. Founded in 1929 by Claude Reed, the company plant was located at 3106 North 24th Street. They sold up to 22,000 cones a day in Council Bluffs and Omaha. They were also notorious for their segregation practices, both forcing African Americans away from eating in their stores and refusing to hire Black workers until a prolonged protest of their business led them to hiring an African American in the 1950s. The business moved from Omaha less than a decade later.

By 1955 there were a few commercial buildings along Ames Avenue and North 30th Street. Two businesses along North 30th Street included the Wax Paper Products Company and the Independent Biscuit Company. Other businesses in North Omaha included the Vercruysse Dairy, located on the southwest corner of North 52nd Street and Ames Avenue, and more than 100 others. The North Omaha Business Men’s Association made numerous contributions to Omaha commerce, culture, and education.

A Great Big Party

During this period early Omaha banker Herman Kountze owned a large parcel of land in North Omaha, which he platted as a subdivision called Kountze Place. An early homeowner in the neighborhood was John P. Bay, the co-founder and owner of an ice company in Florence that supplied to the railroads, breweries and packing houses of the Midwest. His home was built at 2024 Binney Street in 1887.

On May 17, 1883, Buffalo Bill founded his famous Wild West, Rocky Mountain and Prairie Exhibition in the aforementioned Omaha Driving Park. More than 8,000 people attended the first exhibition at a location near 18th and Sprague Streets. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show later returned to North Omaha for the Trans-Mississippi Exposition in 1898. Held in conjunction with the Expo, an Indian Congress drew more than 500 American Indians representing 35 tribes to the area, as well.

The year after the Trans-Mississippi Expo, North Omaha also hosted the Greater America Expo in 1899. This expo wasn’t as successful, as broad or as purposeful as its predecessor.

Kountze Place

Kountze Place developed mightily after the Trans-Mississippi Exposition, with developments including large homes and several mansions built around the Expo’s only remnant, Kountze Park, which was finished the year after the Expo in 1899. A number of other landmarks were built in Kountze Place after the Expo. They included the beautiful Sacred Heart Church finished in 1902 at 2206 Binney Street; the George Shepherd house, erected in 1903 at 1802 Wirt Street; and the George Kelly house built in 1904 at 1924 Binney Street; and the The Charles Storz House located at 1901 Wirt Street.

Later, North Omaha grew major parks in the form of Miller Park, Fontenelle Park and Adams Park, all connected by the city’s extravagant boulevards system.

Omaha’s Boulevard System

Strolling easily throughout North Omaha was a seemingly luxurious, comfortable drive for the city’s new automobiles. Starting downtown and flowing up Florence Boulevard all the way north, you could take JJ Pershing Drive out of the city, or wind down through Minne Lusa Boulevard and through Miller Park. Then you’d take Belvedere Boulevard west to Fontenelle Boulevard, then travel through Benson. When you got there you could catch Military Road to Dodge, go east until you got to Turner Boulevard, then start all over again going north on a completely different route! It was an amazing time.

Education

Schools were built throughout North Omaha during the middle history of the area. One shining example was Technical High School, constructed in the 1920s to serve North Omaha. While it closed in the 1970s, today the building continues to serve as the Omaha Public Schools District Offices. The Reddick Mansion, mentioned earlier, was originally built in 1875. In 1909, it became the home of Omaha’s municipal college, locally known as Omaha University. For almost 30 years after, Omaha University grew in North Omaha, including lecture halls, residence buildings and a large gymnasium. The football team played on a large, well-developed field at Saratoga School and the neighborhood was a proud host through the 1930s. The North Omaha Businessmen’s Association was responsible for developing a new athletic field at the original Omaha Municipal University in 1928,. Then, in 1937, the University of Omaha moved to Dodge Street, and North Omaha’s higher education was almost lost. Another early builder in the neighborhood was the Omaha Presbyterian Theological Seminary, which built a 40-room school for ministers at 3303 North 21st Place in 1891. It operated in the neighborhood through 1943. In the 1970s, that building was demolished and in the 1980s was replaced with modern apartments. The Metropolitan Community College, originally known as Metropolitan Technical College, was opened at Fort Omaha in the heart of North Omaha in 1974, and today is the only higher education organization operating in the neighborhood.

Military

In the 1860s, Omaha City fought hard to land an Army outfit to guard the city’s new railroad, the Union Pacific. At Omaha, the U.P.R.R. intersected conveniently with the Missouri River boat trade and the wagon trains.

Everyone seemed to be heading west across the Great Platte River Road, the Oregon Trail, the California Trail and other roads west. Since the United States was aggressively attacking American Indian tribes all across the West, the pioneers knew they needed military protection. After originally building their barracks in the present-day Near North Side, Herman Kountze’s brother Augustus offered the Army a cheap deal on 70 acres of his land. They accepted the offer, and Fort Omaha was born. It served forts throughout the Plains and up the Missouri, supplying them with soldiers, reinforcements and more as the years went by. Around the time of World War I, North Omaha was home to the Florence Field. The field was home to huge blimps that were intended for reconnaissance and bombing, and their flyers saw action in France throughout the war. In the 1960s the US Navy leased a parcel of the Fort’s property to build a US Marine Corps Reserve facility at North 30th and Laurel Streets.

Churches

Many important churches flourished during this period of North Omaha’s history. They included St. John’s African Methodist Episcopal, Salem Baptist, Pearl Memorial Methodist Episcopal, and others. Catholic parishes grew extensively with new Irish and German immigrant families. Holy Family Church, Sacred Heart Church and School, St. Philip Neri, St. Richard and St. Bernard were some of the early churches serving neighborhoods around North Omaha. St. Benedict was established for Activities in North Omaha, particularly the locating of the Nebraska State Fair at the Omaha Driving Park, led to the formation of the civic and business association Ak-Sar-Ben in 1895.

Getting Around

The importance of several arterial streets was confirmed in a prominent business journal in 1890, that noted, “North Sixteenth, Cuming and North Twenty-fourth streets on the north and northwest are… prominent business streets, radiating from the commercial center into the resident portions of the city.” There were also streetcars for more than 75 years, and interstates for more than 50. The city’s boulevard system was introduced and popularized during these years, and several subdivisions were built for their walkability and bikability at the turn of the 20th century.

Huge Weather

North Omaha has suffered in severe Plains weather. In 1902 a major early spring storm demolished a lot of the neighborhood in the Monmouth Park neighborhood. The tornado-like activity destroyed the original Immanuel Hospital and closed North Omaha’s Franklin School.

The most significant weather-related event to hit Omaha was the Easter Sunday tornado of 1913 that destroyed many of the area’s businesses and neighborhoods. It cut a path of destruction through the city that was seven miles long and a quarter of a mile wide.

In the city as a whole, 140 people died and 400 were injured. Twenty-three hundred people were homeless; with 800 houses destroyed and 2000 damaged. In the 1913 Easter Sunday Tornado, the Idlewild Pool Hall at 2307 North 24th Street was the scene of the greatest loss of life. The owner, C. W. Dillard, and 13 customers were killed as they tried to take shelter on the south side of the pool hall’s basement. The victims were crushed by falling debris or overcome by smoke from fires begun when wood stoves used for heating overturned.

North 24th Street was laid waste. The victims were removed to the Webster Telephone Exchange Building. The building was a central headquarters as the community recovered. Operators went to work despite the building missing all of its windows.

Building Communities

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many Jewish immigrants became involved in the Progressive and socialist movements. However, as wealth accumulated within their community and they became more accepted throughout Omaha’s most discriminatory neighborhoods, Jewish people began moving away from North Omaha en masse.

Starting around the 1900s, African Americans began moving into North Omaha. Recruited for jobs by the meatpacking industry, African American migrants doubled their population in Omaha between 1910 and 1920, with a population among western cities second only to Los Angeles.

By the late 19th century, the community already had three churches, which contributed much to its life. The African-American community culture in North Omaha developed a musical legacy of blues and jazz through the 1950s.

In 1938 Mildred Brown and her husband founded the Omaha Star newspaper, since 1945 the only black paper in the state. Brown kept it going by herself for more than 40 years until her death in 1989. Since her death, her niece took it over.

In the late early history of North Omaha, many civil rights groups were established in North Omaha. By the 1930s and 40s, the black community together with white labor organizing partners worked against the segregated practices of the meatpacking plants. Through their organizing the interracial United Packinghouse Workers of America, part of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), they began to win concessions from management. The UPWA was integrated and progressive, also supporting integration of public facilities in Omaha, and the larger Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. At the same time, many ethnic fraternities in North Omaha closed or morphed, becoming open to general populations who spoke English. The European-language churches built all across North Omaha between the 1870s and 1920s all converted to English during this era, and places like Danish Vennelyst Park went from being ethnic enclaves to being open for anyone who could afford to use the private spaces.

The Area Changes Again

After World War II, the area changed again.

African Americans came home from the war and wanted to experience the freedoms they’d earned around the world for others. In Omaha, they faced deep discrimination, including segregation in employment, housing, law enforcement, education, and other areas.

All wasn’t grim though. In the 1940s, North Omaha was the home to the African-American players of the Omaha Rockets independent baseball team. The team played exhibition games against Negro League teams from across the U.S. It had several important players. Many of the hopping clubs from before the war had closed, but stalwarts like the Dreamland Ballroom and the Carnation soldiered on with good times.

Many African Americans were self-employed during this time, working off the books as house cleaners and day laborers. Some found stable and well-paying employment in the packinghouses of South Omaha, commuting everyday from North Omaha there.

During that same era, 15,000 people worked in the meatpacking industry in Omaha, but within a decade, fully half the city’s workforce worked in the meatpacking industry. Omaha became the largest meatpacker in the United States. As the packing industry changed in the 1960s and moved operations closer to the meat producers, Omaha lost 10,000 jobs. This meant a loss of political power as well for African Americans and other working-class people.

At the same time, North Omaha’s white neighborhoods were flourishing. The working class Europeans were building wealth and prioritizing affording higher education for their children, sending kids far away to Lincoln to go to the University of Nebraska, or keeping them near home to go to the newly-minted University of Omaha campus on West Dodge Road. Omaha University was ripped from North Omaha in the mid-1930s, and the new campus was established in 1937.

Many of the hospitals established in North Omaha in the early history of the community were closed during the middle history of the area, too. The Swedish Mission Hospital on N. 24th became the Evangelical Covenant Hospital in 1928, and that closed permanently in 1937 because of the Great Depression.

White Flight

During the middle history of North Omaha, the northern European immigrants who founded the Near North Side moved north towards Florence, building up the Minne Lusa Historic District, the neighborhoods along Fontenelle Boulevard, and all of Florence. African Americans took over the Near North Side, taking on many of the homes, apartments and businesses. They also patronized the remaining Jewish-owned businesses, all that was left of the once-burgeoning N. 24th Street. African Americans in Omaha managed to break through the redlining designed to keep them in the Near North Side during this era, too, moving northward into the once-lavish Kountze Place district.

However, just under the surface the area was boiling. Neighborhoods started fluctuating wildly during the middle history of North Omaha, as white flight took hold and white privilege flared its ugly head. White people began abandoning the area quickly by the late 1950s… but that’s for the next installment of this history!

Leave a comment