Before the Indian Territory now called Nebraska was opened for American expansion, African Americans in the region were fur trappers and traders, western pioneers, farmers, and more. They were also enslaved in the region. This is a history of Black people in the Omaha area it was established in 1854.

Native Americans First

American Indian nations lived in the Omaha area for thousands of years before European Americans, African Americans and others showed up. This first section is about the Omaha region before Europeans began striking at the region in the 1600s.

American Indian nations have lived in the Omaha area for thousands of years, long before European Americans, African Americans and others showed up and still today. They are the caretakers of the land whose livelihood, families, culture, and overall ways of being is inherently tied to the land. For decades before it happened, European and American colonizers committed genocide, led ethnic cleansing, stole the land, and forced the removal of several nations from the area in order to establish the Nebraska Territory and Omaha City in 1854.

Through time, the Omaha nation came to the area to hunt, living temporarily by the Missouri and Elkhorn Rivers. The Ponca lived throughout the North Omaha region, burying their dead along the cliffs and holding ceremonies overlooking the Missouri River valley. These tribes had sophisticated cultures, advanced agriculture, and deep knowledge in many areas.

It was in the face of those realities that France claimed the Omaha area as part of their territory in 1682. French people from Quebec and France came to the area and trapped, hunted, and established settlements and trading posts across Nebraska and much further. The Spanish took over the region calling it New Spain, and the French fought for it to take it back and called it New France. Neither of these empires asked any American Indian nations who lived here whether they could take their lands. Europeans have constantly exploited the Americas, and so it should come as no surprise that the United States bought the Louisiana Territory without asking the people who actually lived there for thousands of years beforehand.

In this era, the Otoe kept a village along the old North Omaha Creek, and were likely sent there along with the Missouria, Ojibwa, Ottawa and Potawatomi nations who were moved to the North Omaha area as a temporary camping area. That lasted for a few years. While French and Spanish influence were gradually diminishing and American influence was exerted, we get the first written accounts of Black people in the area that was eventually settled as Omaha.

The First Black People in the Omaha Area

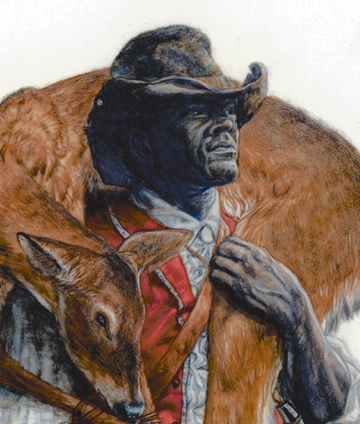

Perhaps the first accounts came from stories of Black people who lived with American Indian tribes in the region around present-day Omaha when the French fur trappers first came into the area in the 1710s. During this era, the Omaha area sat in a colony of the French empire called New France. It was an economic hub for France’s expansion where hundreds of skilled workers called voyageurs trapped and traded with American Indians for valuable furs. It is well-documented that they established hubs along the Missouri River, which they used as a highway for their work. Among these voyageurs were freed and enslaved Black men, some of whom might have reached the Omaha area. Their histories have been largely neglected and the stories are nearly all lost, with none actually accounting for their arrival in Nebraska.

It is known that in 1720, Black soldiers arrived in the region near Omaha as part of a Spanish expedition led by Lieutenant-General Pedro de Villasur. This conquistador reached the Platte River west of Omaha before being repelled by a joint force of Pawnee and Otoe warriors. There was a “massacre” of Villasur’s soldiers near present-day Columbus, and one of the men who died was reportedly Black.

France gave Spain the New France colony in 1762.

Black Explorers & Fur Trappers

In 1800, Spain gave the land back to Emperor Napoleon. The stage was set for more Black people to come to the area when the United States bought the colony in 1803. Renaming it the Louisiana Purchase, the first formal American expedition was sent to cross the continent in 1804.

The first recorded Black person to arrive in the Omaha area was York (1770–1832), an enslaved man who belonged to William Clark of the Lewis and Clark expedition. York was born to parents who were enslaved in Virginia in 1770. After growing up property of William Clark’s father, York was given to younger Clark in 1799 when his father died. The same age as his new owner, York was granted a lot of autonomy during the expedition. He was the only Black person on the expedition, and became the first Black person to travel across North America. According to Clark’s journals, in addition to his formal role as a laborer, York had another important role on the journey. Apparently the American Indian tribes were intrigued by his skin, and because of that several tribes gave the expedition passage when they wouldn’t have otherwise. Clark named a group of islands in the Missouri River in Montana after him. However, despite being promised his freedom after the expedition ended in 1806, York remained enslaved. He died in 1832 of cholera.

There is some disagreement about whether Jean Baptiste Point du Sable (p.1750–1818) might have been the first African American to live in the Omaha area, even temporarily. In a 1968 Omaha Star column, a noted Omaha historian named Harold W. Becker identified Jean Baptiste Point du Sable as one of the Black trappers who worked with Manuel Lisa. Point du Sable worked for a Spanish-American fur trader named Manuel Lisa (1772-1820), who kept a base near the foot of present-day Hummel Park called Fort Lisa until 1820. As a trader, Point du Sable regularly worked out deals with American Indian tribes throughout the region to bring furs back to the base before they were shipped onto St. Louis. Before he worked in the Omaha area, Point du Sable is credited with establishing the present-day city of Chicago in the 1780s. After he worked at Fort Lisa until 1814, Point du Sable returned to his home in St. Charles, Missouri, where he died in 1818.

Major Stephen H. Long (1784–1864) came through Fort Lisa in 1819, and reported there were Black pioneers at the site. One of them might have been Edward Rose (c1780-1833), a Black trapper who worked with Manuel Lisa frequently and was noted to have stayed at Fort Lisa in 1812.

According to scholarship by Kenneth W. Porter (1934), Lisa’s traveling cadres that left the Omaha area regularly included Black men, including George, probably enslaved as a cook or personal servant; Rose, who acted as an interpreter and hunter; Point du Sable; and Cadet Chevalier (17??-1813), a freeman who was a trapper.

Black people who worked in the fur trade industry were generally freemen. However, as this account shows, there were enslaved people in the forts, too.

Enslaved by Army Officers

Before 1862, there were antibellum Army officers in the Nebraska Territory who were enslavers. They were at the Missouri Encampment near North Omaha from 1819 to 1820, and subsequently at Fort Atkinson from 1820 to 1827 near present-day Ft. Calhoun. While this isn’t exactly in North Omaha, its close enough for me to include here. A project by the current (2024) curator at Fort Atkison, Susan Juza, has identified some of the enslaved people at the fort. Some of the most noted enslaved people at Fort Atkinson were owned by James Kennerly, a cousin of USA explorer William Clark who was the fort’s sutler. Kennerly owned several enslaved people, including Frederick and Rubin. These enslaved people were said to be allowed to socialize with enslaved people at the nearby Cabanné’s Post during Christmas events.

However, from 1822 to 1840, a French company ran a fur trading post on Ponca Creek called Cabanné’s Post. John Pierre Cabanné (1773–1841) was a French fur trader from St. Louis, and he owned at least one enslaved person at the post.

Additionally, its recorded that renowned Black mountain man James Beckwourth (1800-1866), who was a formerly enslaved man, traveled through Fort Atkinson more than once.

To stop disagreements between enslavers and abolitionists and begin the process of opening the Louisiana Purchase for settlement, in 1820 the United States Congress passed the Missouri Compromise, which was supposed to stop enslavement in the land that eventually became the Nebraska Territory.

The topic of slavery in Nebraska would not be revisited by Congress until 1854.

The Gold Rush Era

From 1848 to 1860, Black migrants traveled through the Omaha area on their way to California and the Oregon Territory to search for gold. Heading to California, about 2,000 Black “forty-niners” (as the fortune seekers of 1849 were called) went to the goldfields, with 250,000 total of all races making it there by 1853. Other gold rushes with Black miners who traveled through the Omaha area included Virginia City, Nevada (1859–60); Cripple Creek, Colorado (late 1850s and 1890s), and in the Black Hills of South Dakota (1876–78). I haven’t found any direct evidence of these Black gold seekers living in the Omaha area or staying for any extended period of time, but given its location on the California Trail and the US Army’s path for the Military Road, its certain that many at least traveled through the area and likely through North Omaha.

The Omaha-area story of an enslaved man named Tom Brown starts in 1842, when he came to today’s downtown with his owner’s hunting group in search of bison. Staying in an Otoe village located on the present-day site of Creighton University, Brown eventually ended up escaping from his owner to Canada. Coming back to the United States after the Civil War, in 1907 Brown moved back to Omaha, where he lived until he passed away at 95 years old.

However, I have found no record whether any stayed in the area or were buried in the city’s present-day boundaries.

Traveling With the Mormons

When the Church of Latter Day Saints pioneers established Winter Quarters in present-day Florence in 1846, there were reportedly several Black people among them. Listed as “colored servants” because the church informally did not allow Black members, the group included Hark Lay Wales (1825–1881), Oscar Crosby (c.1815–c.1872), Green Flake (1828–1903), and Jane Manning James (1813–1908). With several of these people referred to as “domestics,” there were also laborers among the enslaved group who “repaired wagons, organized supplies and gathered firewood.” Several of their enslavers came from Mississippi along with others from Maryland.

In addition to those mentioned above, there were other enslaved people at Winter Quarters. William McCary (c.1811-1854) was an African American convert to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints who came to Winter Quarters and was taken in by church leaders for his leadership abilities. However, in 1847 he apparently claimed to be a prophet and started leading members in the Nebraska territory and was excommunicated soon afterwards. The first Black person known to be buried in Nebraska was associated with the Latter-Day Saints and was buried in 1848. A white enslaver traveled through Winter Quarters with eleven enslaved people included on his property list. One of them was Jacob Bankhead (1829-1947), who died of an unknown cause near Council Bluffs and was buried at the Mormon Cemetery in North Omaha.

While their lives proceeded beyond Omaha, each of these Black pioneers—enslaved and free—left an indelible mark upon the land that still resonates today.

Setting the Stage for the Future

On foot, with canoes, wagons, horses, mules, oxen, and sheer determination, Black people lived and moved throughout the region that became Omaha long before the city was founded. As trappers, enslaved people, hunters and more, people of African descent experienced the beauty and fear of the untamed lands around the Missouri River valley.

While written accounts of their successes with tribes are few, those that exist today attribute a lot of white America’s ability to form early relationships with American Indian nations as contingent on the Black men who traveled with these groups as interpreters, hunters and more.

Imagining the smell of smoky creekside campfires, the rustle of untouched leaves underfoot across wooded hillsides, and feelings of exhilaration and challenge in the frontier lands of that era can allow us to begin to understand the realities faced by these pioneers. However, along with the bears, wildcats, elk and bison who might have filled these explorers with fear, the first Black people in the Omaha area lived with a constant threat of white hatred and resentment. Some fought against it actively while others strove for acceptance, while others gave in and still others continued in enslavement.

As history proceeded, Black Omahans went beyond these generalizations and became increasingly distinct figures with important roles in their own lives, throughout the African American community, and across the entire city of Omaha. However, as the first era shows us, they were standing on the shoulders of giants.

In 1853, a group of wealthy white land prospectors in Iowa established a ferry to carry settlers across the Missouri River. There is a popular story of this group informally founding Omaha City with a lovely picnic in the prairies covering the hills in present-day downtown Omaha where Central High School is on July 4, 1854. An early account of Omaha’s Black history tells an 1854 story of an enslaved Black person who belonged to a Native American woman, but that hasn’t been corroborated. However, the presence of enslaved people in early Omaha is undeniable.

1854, the first year of settlement in the new city, included stories of Sally Bayne, who was noted as the city’s first Black resident, arriving in 1854 as a freewoman. The city’s first Black businessman named Bill Lee opened a barbershop in the Douglas House hotel in Omaha soon after.

From that point forward, Black people have continued to leave an indelible mark on Omaha history. However, the things done by people before the city was founded have been largely unacknowledged—until now.

Recognizing these Pioneers

Today, some of the Black pioneers with the Mormons are honored in Salt Lake as the first Black settlers there. However, as of 2024 the grave of Jacob Bankhead remains unmarked though. There are no mentions of Black trappers in history plaques for the places in Omaha where they were, and most history accounts are devoid the role of enslaved people in pioneering the Louisiana Purchase before it became the Nebraska Territory. In 2001, President Bill Clinton posthumously made York a sergeant, but as of 2024 Omaha does not have a historic marker, statue, or other public honor for this important figure from the city’s pre-history.

Perhaps one day the City of Omaha, the State of Nebraska and people all throughout Omaha will come to understand and honor the roles played by the early Black people in Nebraska.

Author’s note: Do you know more? Have a question, concern or criticism? Learn your remarks in the comments section and I’ll reply!

You Might Like…

Elsewhere Online

- “Black Homesteader Project” from the University of Nebraska Center for Great Plains Study

- “Buffalo Soldiers at Fort Robinson” by History Nebraska

- “Buffalo Soldiers of Fort Niobrara” by the National Park Service

- “Buffalo Soldiers of Western Nebraska” by Katherine Rupe for Trails West

- “The early history of Omaha from 1853 to 1873” by Bertie Bennett Hoag for the University of Omaha

- “Negroes and the Fur Trade” by Kenneth W. Porter for Minnesota History, Vol. 15, No. 4 (Dec., 1934), pp. 421-433.

BONUS

Listen to my podcasts related to this article.

Leave a comment