Adam’s Note: This is a special contribution by guest author Ryan Roenfeld. This history shares many important lessons about Omaha’s diverse past, racist attitudes, and the dreams of a better life brought to America by immigrants. Share this with your friends, and let me know your thoughts in the comments section below!

It was all gone by May 1982 when the World-Herald wrote 66 year old Carl Chin “was young when Chinatown disappeared.” Carl’s father was Chin Ah Gin who founded the Mandarin Cafe and then established the famed King Fong’s. If Chin Ah Gin ever bothered, he would have found his name spelled several ways during his many years in Omaha. The 1982 newspaper files and Carl Chin both agreed the “tong house” at 111 North 12th Street was the center of Omaha’s Chinatown that consisted of “four square blocks around”. The newspaper claimed “several hundred people of Chinese descent lived there” with “Chinese symbols everywhere”. Today, there is no evidence it ever existed.

Chin also told the newspaper of the “peaceful” situation of the Omaha tong, a memory not shared with historical accounts, along with the requisite reminisces of “street dances” during the “Chinese New Year”. When the “good-luck hon character” danced in front of a certain store “the owner would hand over money wrapped in lettuce leaves” as some traditional sort of thanks. There was also “secret gambling” going on with “mah-jong games in the back of some of the stores”.

There had been plenty of not so secretive gambling around that neighborhood once dubbed “Hell’s Half-acre” by the Daily Bee. One neighborhood landmark was the sinful St. Elmo, a donnybrook combination of dance hall, variety show, saloon, brothel, and gambling den Jack Nugent opened in 1880 on 12th Street between Douglas and Dodge. The old St. Elmo changed its name to the Theatre Comique and then to the Buckingham but maintained the same infamous reputation for debauchery, robbery, and sometimes murder. Then, in June 1885, the Women’s Temperance Union got a hold of the building as the former “Variety Dive” became an important landmark for Omaha’s Chinese community as the place where many of them first learned to speak English.

The book E Pluribus Omaha by Harry Otis and Donald Erickson places up to 300 Chinese immigrants in early Omaha. As common throughout the West, the majority of Omaha’s pioneer Chinese came from Guangdong and Cantonese language, customs, and cuisine long dominated the local community. The Albert Law closed the wide-open bordellos in the early 20th century while the neighborhood around Omaha’s Chinatown became the “main line” dominated by flophouses and pawn shops where thousands of homeless transients passed through on the bum across the country or just to get a bowl of beans on their way to Jefferson Park.

The exotic presence of the Chinese in Nebraska’s metropolis seemed to both attract and horrify the city’s newspapers all at the same time. After all, the Bee was more accustomed to instigating racial tension to sell newspapers than anything. The World-Herald likewise remained filled with comments concerning “celestials” and “washee houses” well into the 20th century. All of the names here are just phonetic conjecture as well as the plain descriptive “Chinaman”.

The story Wan Lee, the Pagan by Bret Harte was serialized in the Bee newspaper over the summer of 1874 and that October the newspaper questioned “Can’t the Chinese be trained to eat the grasshoppers?” That dilemma “agonizes the heart of one section of the great west” while another was “Can’t they train the grasshoppers to eat the Chinese?” Such sentiments over Chinese immigration to America fueled passage of the 1875 Page Act that ended Chinese contract labor in America and also stifled immigration of most Chinese women. This was followed by the even more restrictive Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 as America’s first immigration policies were specifically designed to keep out a certain sort of immigrant.

The Washee Shops and Opium

By and large, it seems Omaha’s Chinese were usually ignored except for New Year celebrations or when crime was involved. This was especially true when it came to opium. On April 30, 1885 the Bee called on Omaha to “Throw out the Opium” with Mayor Boyd determined to enforce “Some of the Violated Ordinances” and shut down “the opium joints” and even force saloons to “close their doors at midnight and on Sunday”. A few days later on May 2 came the first details of the opium crackdown with 18 Chinese charged “for the first time in the history of the city of Omaha” with “keeping opium joints, or being inmates thereof”. All the “celestials” had lawyers who got their cases continued with around half of them “released on bail, while the others are still in jail awaiting trial.” Their names as given by the Bee were Hi Chung, Lang Ching, George Chinaman, Hong Lee, Tom Chinaman, Hing Ching, Wah Sing, Suh Wah, Tong, Wah, Shuh, Leo Gib, Yough, Stone Hi, Wing Lee, Sing, and Jim Gough.

A small glimpse of Chinese culture in Omaha appeared in the Bee on February 4, 1886 with “Coolie Laundrymen Celebrating Their Glad New Year”. This was the “twelfth anniversary of the accession of Quon Soi, the Son of Heaven, Prince of Earth and Emperor of all the Chinas” and “was celebrated in Omaha yesterday with far grander ‘éclat’ than the run of fairs would seem to warrant.” Omaha’s several “washee shops” closed as Chinese residents “arose with drowsy minds full of meditation”. Then, “Shrines of painted cloth and grotesque picturings were reared, and in their center set a figure of hideous mien about which incense tapers were lighted.” The “devotees of the great and awful Buddha fell upon their knees and wrestled for an hour with heaving prayers and mystic incantations.”

To the newspaper reporter this all seemed “strikingly similar to the common practices of New Year’s day in this country”. For the Chinese, “the day is spent in calling, and each washerman receives his visitors with good cheer” as in “every shop there is a spread of good things, such as hit the palate and fancy of the Oriental” with “Mysterious confections, quaint paper scripts which are greeting cards, cigars, cigarettes, opium pipes, and an endless quantity of quaint and curious articles are laid out and the caller helps himself according to his taste.” Every visitor “may take a snack of cake, or eat black taffy from a dark, forbidding pot or ‘hit the pipe’ a soothing lick, just as he wishes.” The Bee reporter was “cordially received at every point and intrepidly helped himself on pressing invitation” although “It is to be said that some courage is required to swallow Chinese delicacies, as their appearance is all but alluring.” All the same, “the candies and sugared fruits are palatable, and the cigars are genuine tobacco, while the opium smells as strong and probably work as damagingly as the ordinary drug of commerce.” It seemed the Chinese originally planned “a grand blow-out in the W. C. T. U. hall, where they attend Sunday school” and the old theater of the St. Elmo was covered by “lanterns and banners when suddenly they changed their minds and took down the ornamentations.” Instead, the “night was passed at high revelry at all the wash shops in town.”

Dr. Chang Gee Wo

In an era dominated by mail-order medicine and quack cure-alls, the June 5 and 7, 1891 issues of the Bee included half-page advertisements for Dr. C. Gee Wo, “the Chinese physician who after a lifetime of study in China among 500,000,000 people comes to this country locates at Omaha, and in two years earned such a golden reputation that his name is on every tongue.” The “Chinese physician” was based at 519 1/2 North 16th Street with “Office Hours from 9 a. m. to 9 p. m. Every Day” and “Consultation Free”. The Chinese doctor claimed to be a graduate of the National Medical College in Beijing, first in his class, and there were numerous testimonials from various Omahans as to his prowess. There was even examples of “Remarkable Cases Abandoned by Other Doctors but Cured by Dr. Chang Gee Wo”. For those who “could not come to Omaha” Dr. C. Gee Wo offered seven varieties of patent medicines at $1 each, including a “Last Manhood Cure”, “Sick Headache Cure”, and “Female Weakness Cure”. Dr. C. Gee Wo’s medicines were “Put up by the Chinese Medicine Co; headquarters and main offices Omaha, Neb” and a “Chinese office” in Beijing.

There was another advertisement in the Bee in January 1895 for Dr. C. Gee Wo wondering “Who Is He!”. Dr. Wo then advertised as “one of the most skillful of Chinese doctors” who “guarantees a cure in every case or the money will be refunded.” By then he apparently occupied all of 519 North 16th Street, a locality presently occupied by Sol’s Jewelry & Loan. Dr. C. Gee Wo later moved his medicine company to Portland, Oregon where an 1907 advertisement gives the address of his “Chinese Medicine Company” at 162 1/2 1st Street. By 1924, he had moved to 262 1/2 Alder Street in Portland.

Immigration

On February 21, 1899 the World-Herald reported a round-up of 15 “South Omaha Chinamen” who “marched up N Street and boarded a streetcar” with “Deputy United States Marshals” Hank Homann and Jim Allan. It seemed an “inspector from Washington” who “rounded all Omaha and South Omaha Chinamen up at the federal building”. The newspaper reported that an “Omaha Chinaman” named Leo Guy had “escaped the officers” to warn the Chinese community in South Omaha “that something awful was going to happen”. Still, it seemed the “federal deputies, with the aid of the police” rounded up all the Chinese, including Hang Ho, Lu Ty, Ling Fee who all tried to escape before they were assured “no harm would befall them”.

Chinese immigrant Joe Wah Lee was featured in the Bee on August 19, 1900 when the Bee profiled what it considered Omaha’s most prominent Chinese citizens accompanied with photographs by Louis Bostwick. Photographs included Joe Wah Lee, “The Richest Chinaman in Omaha”, along with a view of the exterior of the Bon Ton “Chinese restaurant”, a “Typical Omaha Chinese Laundryman”, and Jo Sing taking the Civil Service Examination. The Bee called the Chinese community “One of the most exclusive sets in Omaha” and “the desire of the hundred or more natives of the Flowery kingdom who reside in the city is to be let alone to their own peculiar devices.” The newspaper thought that they had “no interest, generally, with the community in which they reside further than to be paid for the work they perform” and after “they have received their wages they retire behind the real or assumed indifference of ignorance, and it is a persistent American who can draw them into conversation.” The Bee believed that the “present trouble in China has increased their natural reserve and today there is but one Chinaman in the city who will converse with an English-speaking citizen on equal terms.”

The newspaper considered there was “but one place in the entire city where the Chinese character can be studied and that is in the Sunday school which meets Sunday afternoon during the fall and winter at the First Presbyterian church.” The organization originated “in the old Buckingham home” in September 1885 and then moved to First Presbyterian “where it is now maintained under the supervision of Mrs. John C. Morrow.” In the “Sunday school the taciturn become communicative and the exchange of ideas between the pupils and the teachers is sometimes very interesting, especially for the teacher, who from time to time is cornered by some question of Oriental casuistry or has some of her fondest hopes shattered by some point-blank statement from one of her most promising pupils.” The Chinese Sunday school was “not primarily a place for the dissemination of religious ideas, but that phase of the work comes up incidentally.” The “first effort of the teacher is to instruct the pupil in the rudiments of the English language” and “books have been printed with English and Chinese text and from them the teachers, many of them with no idea for the Chinese language, are very successful in their work.”

Omaha’s Chinese community “are practically all from the city of Canton, and coming from one place are all the more clannish in their home life.” The Bee considered the Chinese as “peaceable, quiet and law-abiding, their only appearance in the courts being caused by the national habit of opium smoking, and even this is falling into disuse with many of the Omaha. colony.” It was “Joe Lee, or Joe Wah Lee, as he is known in private life” who was “the recognized leader” of Omaha’s Chinese. The newspaper called him the “best interpreter in the city and has a sound knowledge of the English language.” He was also “one of the few Chinamen who will discuss affairs relating to his race with Americans.” Joe Wah Lee was “reputed to be the richest and one of the shrewdest Chinamen in Omaha” who “runs a restaurant on East Douglas street and as chef is said to be one of the best men in the west.” At the time he was “an applicant for a position as interpreter in the government service and expresses a desire to be sent to China with the army.” The China Relief Expedition was then headed to China towards the end of the Boxer Rebellion which sought to end both Western imperialism and Christianity.

Other members of Omaha’s Chinese community included Leo Mun, the “head of the Quong Wah company” who was “credited with being the best educated Chinaman in his native language in the city, being able to read at a glance all of the 40,000 characters of the Chinese alphabet.” Mun was “deeply learned in the theology of his native land, but is very reticent because of his ignorance of English.” There was also “Hong Sling, or Henry, as his Christian name has been translated.” He had moved from Omaha to Chicago and was passenger agent for the Union Pacific, Northwestern, and the Southern Pacific railroads. He had started out as “a section hand on the Union Pacific” before he was promoted to storekeeper in Pocatello, Idaho and then Ogden, Utah. Hong Sling later “had charge of the Chinese construction gangs on the Rio Grande and Union Pacific” railroads but “lost money” trying to sell “Oriental goods” at the Chicago World’s Fair. After that he went back to work on the railroad.

The Bee profile continued that during the “last registration of the Chinese” included in the “internal revenue collection district of Nebraska” found 502 Chinese natives. Of those, Deadwood “had the largest Chinese population, while Omaha was among the towns having small colony” of just 81. There were “many of those” who registered at Omaha who had since moved although “their places have been taken by others.” The newspaper counted 20 “or more” former residents who attended Omaha’s Chinese Sunday school had gone back to China and “many of them correspond with their former teachers and claim to be following the teachings of the western light.”

Unsurprisingly, the “principal occupation” of Omaha’s Chinese community was “laundry work”. The Bee explained that “the marks on the bundles of clean linen, duplicates of which are in the pockets of the patrons” were “‘good luck’ mottoes” and labeled the Chinese “a believer in spells and incantations”. Not all the Omaha laundries included them “but many of the houses give their patrons not only clean shirts, but a Chinese blessing for their money.”

Chop Suey

The Chinese laundries had been running for years in Omaha before Americans seemingly found a taste for Chinese cuisine. In the early 20th century, that meant chop suey. In April 28, 1905 the World-Herald advertised a likely more traditional version. This was for the Sing Hai Lo Company at 1306 Douglas Street that offered “First Class…Chop Suey” and was open from 10 o’clock in the morning until three in the morning. Yes, they were only closed for seven hours a day. They could be reached via “‘Phone F2327.”

Two years later on September 8,1907 an article in the World-Herald attempted to explain the vagaries of Cantonese cooking. This was by request from Norma Schmidt of Niles, Michigan who wanted a real recipe for “chop suey”. The newspaper related this had “young, tender pork as a foundation” and “in Chinese restaurant parlance” was called “fine chop”. There was also “Guy chop suey” when the main ingredient was chicken or “Mo goe chop suey” with chicken and mushrooms. With “all these” ingredients and brown sauce it was called “See yu, or gee yow”. The brown sauce was compared “to our Worcestershire sauce” and was available from “any Chinese dealer” along with the “bean sprouts or water chestnuts that go with the dish.”

For “gay chop suey” that would “serve six persons you will need one young chicken, cut in pieces, using all the giblets: a pound of water chestnuts, two pounds of bean sprouts”. If those weren’t available, “French peas, tender string beans, or asparagus tips” could be substituted. The rest of the ingredients were “a little sliced celery” and “sliced onion”. Yes it was suggested to “serve over rice” and one should “add a little flour to thicken and salt to taste”. The brown sauce was added at the very end.

By October 1907, the Bee commented on the rising price of chop suey in Omaha although “meat packers say the price of fresh meat has declined”. Charles Yong was called a “Douglas Street suey magnate” and told the newspaper “the price will be advanced several cents a dish on all varieties.” The newspaper believed “the favorite delicacy of the ‘seeing Omaha’ crowd is higher at all restaurants than ever before” but if “chop suey contains fresh meat of any kind is a matter of conjecture.” It did contain green peppers and “the early frosts caught some of the peppers and may be in a measure responsible for the advance the chop suey market.”

The “suey king” Yong explained that chop suey was “the first Chinese dish which Americans learn to order, before they take a chance on ordering the other concoctions, which the Orientals serve.” As it was, “the Chinese say there is meat of several kinds in each dish, the fact remains that few know whether there is or not.” However, for those “who have eaten hash, known as lopadotemach, etc., to the Chinks, believe there is really fresh meat in chop suey, as it has the appearance of an Irish stew that has been dropped on the floor and picked up carelessly.” The “packers say that chop suey should be lower, as they have reduced the price of meat, and that the suey contains chicken or pork, green peppers, celery, barley, bamboo sprouts, liver, water nuts, sweet potatoes, lichee nuts, pineapple and the juice of the siau bean, mixed with fermented beef blood.” There wasn’t “a chop suey magnate in the city” who “will admit that the dish contains the things which the packers claim it does, or that the foundation of the concoction is fresh meat.” Charley Yong “shakes his head doubtfully, but admits that there is always chicken buried somewhere in the mixture which resembles goulash.”

There were photographs of Omaha’s 1910 Chinese New Year in the Bee on February 20 although the celebration was “securely secluded from the eyes of those who do not know and do not understand in some half hidden corner of those many partitioned, odoriferous oriental restaurants on lower Douglas street”. That’s where the “solemn faced yellow people are remembering the world’s oldest fete day – the New Year of China” and was also a celebration of Pi Yu, “the baby ruler of the Celestial Kingdom” who turned four years old on February 11. In Omaha, “one sees the golden dragon signs along Douglas street” and “Slow, slender filmy lines of smoke” that “rise from funny little regiments of punk sticks standing on a table bedecked as only by the art from out of the East.” There were “strange smells of garlic-like pungency” for the “Chinaman’s New Year feast, all to the glory of Pi Yu and the land of his forefathers over the Pacific.”

Decorations included “a cloth of daring brilliant color, rarely stitched in weird fantasies of dragon design and unchristian scrolls” on which rested “plates of rich enamel, through which gleams artfully traced lines of ‘powder blue,’ cups with flaming shades of salmon pink and sange de boeuf, vases that make one think of a sea sunset tangles in a simoon.” There were piles “of candied fruits and sweet meats and dainties” of Chinese origin and “bitter sweet ginger roots, crusted in yellowish flakes of sugar and the biting wild tasting shreds of ginseng mixed with ribbons of sugared cocoanut.” There was a “round woven basket with a frieze of rioting fanciful creatures chasing each other about the rim” that contained “the soft shelled raisin hearted nuts from the valley of the Yang-tse-Kiang” and then “in sudden contrast” was “a box of American-made cigars”. There was also a “dwarf tea plant, neighboring with a blossoming primrose” with “packages of yellow and green and red fire-crackers” all “strewn about mingling their gaiety with paper flowers, the like of which never grew on plant or tree.” The paper flowers were “the fairy blossoms of good luck – that’s all, just good luck blossoms, the only kind that the botanist has not tried to classify.” The “Chinamen say” that “they bear sweet fruits”.

In case the “visitor shares the confidence of his tea tinted host he may nibble at the sweet things” and “the Celestial” might even “produce a chubby jug strapped with dust stained labels in funny scrawls of India ink hieroglyphs and set forth tiny portions of green China rice wine, aged in fair Cathay.” As for “the taste” of the drink, the Bee reported it was “not exactly displeasing to the bourbon trained palate, but one wonders what will happen next.” What happened was “tingling sensations” that “spurt through one’s veins as the aroma of the peculiar beverage diffuses” and “discretion bids only the experimental tipple” and the face of “the Chinaman” almost “gleams with a politely concealed smile” at the refusal of a second drink.

A “guest, if he is a knowing one, exchanges his card for his host New Year ‘joy card,’ a slip of rice paper bearing the Chinaman’s name in bold brush printed characters on a field of red rich as blood clots, the glow that alights the hearts of the heathen Chinee.” With that “the door closes behind on the oriental feast tossing the delicate swirls of punk smoke into a chaos of curls” and with a “suave gesture the Chinaman bows you out and the New Year’s call is over.” Then “down the dingy stairs” and back “out into the noisy clatter of Douglas street, here the Omaha bustle and roar wakens one again and there Pi Yu’s birthday seems just a curiously ornate dream.” The “bit of talk, a drink, a smoke, some memories is about all that remains of the Chinese New Year in Omaha” with “but a scant 100 of the baby emperor’s countrymen in the city”. They were “too busily engaged in the altogether modernized chase of the big round American dollar” and “business urges they do not linger long with the native holidays.” Where there was “a community life preserving racial customs in a higher degree, the real fifteen day feast is held.”

The “beginning of the New Year means many things to the Chinaman” as “all his debts must be paid and his obligations met” which the Bee compared to the “New Year’s resolutions” of westerners. The Chinese immigrants “ancestors must be remembered with portions of boiled rice and chicken fresh cooked in spices placed on their graves” and he “may not grow angry or vexed while the New Year celebration is one, and the joss sticks must burn steadily in the temple.” The “Chinese New Year is a season of peace on earth and good will toward men, and many firecrackers to keep away divers and sundry devils and malicious spirits” that “combined sentiments of Christmas, New Year, Thanksgiving, Valentine day, the Fourth of July and St. Patrick’s day, if one can imagine such a potpourri of tradition and festivities.” Due to “city ordinance” in Omaha the “firecrackers only form part of the decorative scheme of Chinese New Year”.

Around Omaha, “about the Chinese restaurants and laundries at this season one sees many little red cards bearing a name in English accompanied by an array of the Chinese characters.” These were “remembrance cards sent to former students by the teachers in Chinese missions, many of them from far over in the orient.” There was one “Omaha Chinaman” who had been “receiving a card from his mission teacher each New Year day for eighteen years, and he has come to consider it part of the tradition of the day.” In “curiously good English” he said “I wonder if it means that the Chinese New Year is becoming Americanized or if the American missionary is getting a tinge of the oriental

While the On Leong Tong generally held sway, in June 1910 the Bee noted Leo Lawrence and his father Chi Sang were the only Omaha members to celebrate the 2000th anniversary of the “Four Brothers’ society” otherwise known as the Lung Kong Tin Yee Association, dubbed by the Bee the “Loo Gong Chang Chuu tong”. That tong were traditional rivals of the On Leong Tong.

On October 14, 1910, the World-Herald reported Louie Ahko’s “chop suey house” on Douglas Street was raided by Omaha police who “get beer”. In all, the police confiscated 40 quarts of beer and arrested Louie Ahko, his cook Chin Ten, and three couples in the restaurant “‘drinking’ a new brand of chop suey”. When arrested, Ahko had $212 on his person and Chin Ten had $227 so it seemed “business had been passably good as of late.”

January 1912 was when Gin Ah Chin opened the Mandarin Cafe on the second floor of 1409 Douglas Street. The restaurant featured a prominent Chop Suey sign on the front of the building. An advertisement for the Mandarin in the World-Herald invited the “After Theatre Parties” to attend the opening at 9:30 at night. The “grand opening” was at 10 o’clock the next morning, Wednesday, January 31st, with “Chinese fireworks” and “Souvenir Free To Every Visitor”. Three months later in March, the Mandarin introduced “An Innovation For Business Men” with a “Special Noon Day Luncheon” daily between 11:30-2:30. In addition to the “many appetizing Chinese dishes” there would be “American dishes” including “roasts, steaks, chops, and fish” with a “new Chef, direct from San Francisco”. One Mandarin advertisement in the Bee in March 1913 labeled it “Omaha’s exclusive Chinese cafe” with “Music ev’n’gs”.

While the Mandarin offered Chinese and American cuisine upstairs, one can only consider the full implications of 1409 Douglas Street. On the ground floor was the Budweiser Saloon, the long-time headquarters of Omaha’s political boss Tom Dennison. The connections between Omaha’s boss of the underworld and the local prevalence of opium remain nothing but a subject of speculation.

Just down the street at 1419 Douglas Street was Louie Ahko who advertised the reopening of his restaurant in the World-Herald in April 1912. He’d been closed for three weeks as he’d refurbished his restaurant. As always, Ahko’s was noted for its chop suey and “steaks–the very best obtainable.”

On April 11, 1913 the World-Herald gave a heart-felt, if patronizing, thanks to the city’s Chinese community following the devastation of the Easter Sunday tornado. Truly, “one touch of nature makes the whole world kin” and “there came into the World-Herald office a Chinaman, who modestly failed to leave his name.” The man “did leave, however, $120, and with it a little note – ‘In token of sympathy with the tornado sufferers. From the Omaha Chinese.’” “God bless you, John Chinaman,” the World-Herald continued, “with your yellow skin, your slant eyes, and your inscrutable face with its thousands of years of sad history and patient racial history behind it!” While “Our white man’s money has gone out to your own people in times when the great turbulent floods went pouring over China’s teeming plains” and “missionaries have penetrated the vastness of your ancient civilization preaching that you are our brothers, too” but “the idea never quite got under our skins, we must confess.” After all, “We’ve mocked your pigeon English and your mincing steps and your pig tails – and dreaded you a bit, too, even as we mocked.” The newspaper admitted that “We’ve speculated on ‘the yellow peril’ and read, in the lurid magazines, of how your deft, long fingers were itching to plunge into our very vitals and tear out our hated hearts” and “We’ve idly wondered if you really did despise us as you washed our linen and served us your chop suey and performed your menial tasks with that enigmatic smile forever on your lips.” The newspaper wrote, optimistically, that “It’s different now” and “That $120, earned nickel by nickel; that little note, ‘In token of sympathy for the tornado sufferers, from the Omaha Chinese,’ has taught us more than we could learn from many ponderous volumes.”

The simple gesture by Omaha’s Chinese community was picked up by a variety of newspapers, including the Arizona Republican of Phoenix, Arizona and The Commoner of Lincoln, Nebraska.

That same month on April 15, 1913, the Bee found “Frenzied finance” in Omaha police court after 159 “inmates of the disorderly houses” were arrested and a record amount of $1,342 was collected “for high fines and forfeited bonds”. Judge Foster went through the cases in the place of their arrest with the first 14 coming from Louis Ahko’s “chop suey parlor” at 1419 Douglas Street. Most of them were fined $5 and costs excepting two “inmates” and three “Chinese waiters” all released. Ahko was in California while “his wife, who had charge of the establishment, made her getaway from a rear window when the officers arrived.” Other places raided were “Sam Joe’s Unique cafe, which is also known as the Elite”, Charles Sing’s Turf cafe at 1306 Douglas Street, the Nanking at 1313 Douglas Street which was also “under the generalship of Charles Sing”, the Horseman hotel previously known as the Charles at 1419 Dodge Street, and Bessie Woods’ house at 11th and Leavenworth Street where mostly women were arrested. Ms. Woods failed to show up in court.

In spite of the reputation of local chop suey joints, it seemed a 193? Eastern Star convention held in Omaha seems to have spread Chinese cuisine across Nebraska after “several parties of women were taken through some of Omaha’s oriental restaurants.” One woman “asked for chop suey and yakame recipes and being obliged several score of other women followed suit.” After they had returned to their “Nebraska villages and hamlets” the Bee reported “Omaha restaurant men” were “receiving orders daily for some of the essential ingredients that have to be imported from China.”

Louie Ahko was in the news again on April 12, 1914, when proprietor of Chinese restaurant at 1419 Douglas Street was caught up as one “men and women accused of the abduction and downfall” of 14 year old Agnes Zimmerman. The Bee reported that Ahko’s “chop suey and chili joint” was where Harry McCloud “is said to have made his headquarters.” McCloud and Anna Smith were considered the instigators as police believed Ms. Smith frequented “10-cent stores” to “get acquainted with young girls” and “telling them stories of good times and expensive clothes”. That was the lure to Ahko’s restaurant where they were introduced to McCloud who “would then get other men for ‘escorts’ for the girls and would rent them his taxicab to take them on long trips to distant road houses or hotels.”

Not just a Jewish joke, but in December 1915 the Bee listed several Omaha restaurants that would be open for “Christmas dinner” that year, including the Mandarin which was offering a “Special Dinner, 11 A.M. to 8 P.M. $1.00 Per Plate”. The phone number for the Mandarin was Douglas 2840. Also open for Christmas dinner was the King Joy at 1415 Farnam Street. The King Joy called itself “Omaha’s Classiest Chinese Cafe” with “Finest Chops and Steaks in the City”. Upstairs at 1412 Douglas Street was Louie Ahko’s, “Omaha’s Best Chinese Cafe” offering chop suey, yet-gour-mein, and chili con carne. The phone number of Louie Ahko’s was Douglas 4591.

It was in 1916 when Louie Ahko bought two lots at 51st and Dodge Street where he “planned to build a home”. Due to neighborhood objections, they sold the lots instead of building. According to the World-Herald, Ahko was “the first of his race to own property in the exclusive portion of the city.”

That same year in March Omaha’s Chinese cuisine was blamed in the divorce brought by Edward Nicholson against his wife Irene. They had been married in Council Bluffs four years before and he asked for the divorce on grounds “of cruelty, alleging his wife is too fond of chop suey and frequents chop suey parlors.” The next year a fire swept along the north side of Douglas east of 15th Street and decimated Louis Ahko’s restaurant. He moved to Harney Street.

King Fong’s

On September 14, 1920 the World-Herald announcement of the opening of the King Fong Cafe by the “King Fong Lo Co.” on the second-floor of 315 South 16th Street. That was the former Hanson’s Cafe. The advertisement noted Chin Gin was president, G. D. Huie was secretary, and C.S. Yuen was manager of the new enterprise. The restaurant planned to open two days later at 4 in the afternoon as “a worthy milepost to rapidly growing Omaha.” The restaurant was decorated “from far away Cathay” and included “camphor wood carvings, teak wood tables and chairs, elaborate silk embroideries, and other notable features”. Particular attention was called to the “four Chinese chandeliers in the dining room” that were “the first seen in this country.” It was intended that “East meets west” with an “attractive and unique blending of the oriental with the occidental”.

Tong Wars

By the early 20th century the On Leong Tong dominated Omaha’s Chinese community from their headquarters on North 12th Street. The Bee referred to it as the “most powerful Chinese organization in the world” in January 1920 and detailed efforts by the tong against the opening of an unauthorized Chinese cafe at 1408 Farnam Street. At the time, Soon Lee claimed to be “one of the high officers of the On Leong Tong” who agreed to be interviewed by the newspaper with a translator present but who “avoided questions with a skill with which only the Oriental knows.”

Soon Lee did admit that Omaha’s Chinese Merchants’ association was “simply a local name for the On Leong Tong” and had 100 members who “would tolerate no interference with its wishes.” When asked about the recent skirmish at 1408 Farnam, Soon Lee suggested the newspaper “go talk to King Joy. He tell’y you all ’bout it” before he “hobbled back into an even darker room and would say no more.”

As for Joe Lee, the proprietor of the “California cafe and chop suey parlor” at 1408 Farnam, he “cowered in fear when the name of the tong was mentioned to him”. “I fear for my life,” Lee told the newspaper but still seemed determined to open in spite of the tong. The Bee also noted that a recent issue of the Chinese daily newspaper Chung Sai Yat Po published in San Francisco included a “warning to non-members of the tong in Omaha who dared to oppose members in any manner.” The translation, “death was threatened as the penalty”.

The furor continued at the end of January 1920 when Joe Lee’s attorney John W. Battin threatened federal intervention if there was more interference with Lee opening of a Chinese restaurant at 1408 Farnam. A “warning against nonmembers of the tong” was posted “in Chinese characters of black on an orange background” on the front of the On Leong building on North 12th Street. To Lee’s attorney, the threat in the San Francisco Chinese newspaper made it an issue for federal officials as it was transmitted through the mails. Local sources told the Bee there were once three tongs in Omaha but “One has disappeared” while the “Hop Sui tong” had lost so much of its membership that the “On Leong tong dominates the city”.

Such tong wars always good fodder for the newspapers. It was on October 27, 1924 when Ong Wen was reported killed in Omaha by the Daily Nonpareil newspaper. He was supposedly member of the “Can Wong” tong and was killed by a Chin Hin, a member of that same tong.

Another tong war report out of Chicago appeared in the Southeast Missourian of Cape Girardeau in March 1927. The report in the Missouri newspaper labeled the Hip Sing and Bow Tongs as having “radical membership” in contrast to the “conservative” On Leong and Hop Sing tongs. Sources in the Chicago police placed the “Hop Sings and Bow Tongs” as operating “west of Denver” while the On Leong and Hip Sing tongs had “the bulk of their membership” from Omaha east “to the Atlantic seaboard.”

As for Joe Lee’s California cafe on Farnam, well, it is not much remembered in the annals of Omaha’s Chinese restaurants, is it?

The Death of Louie Ahko

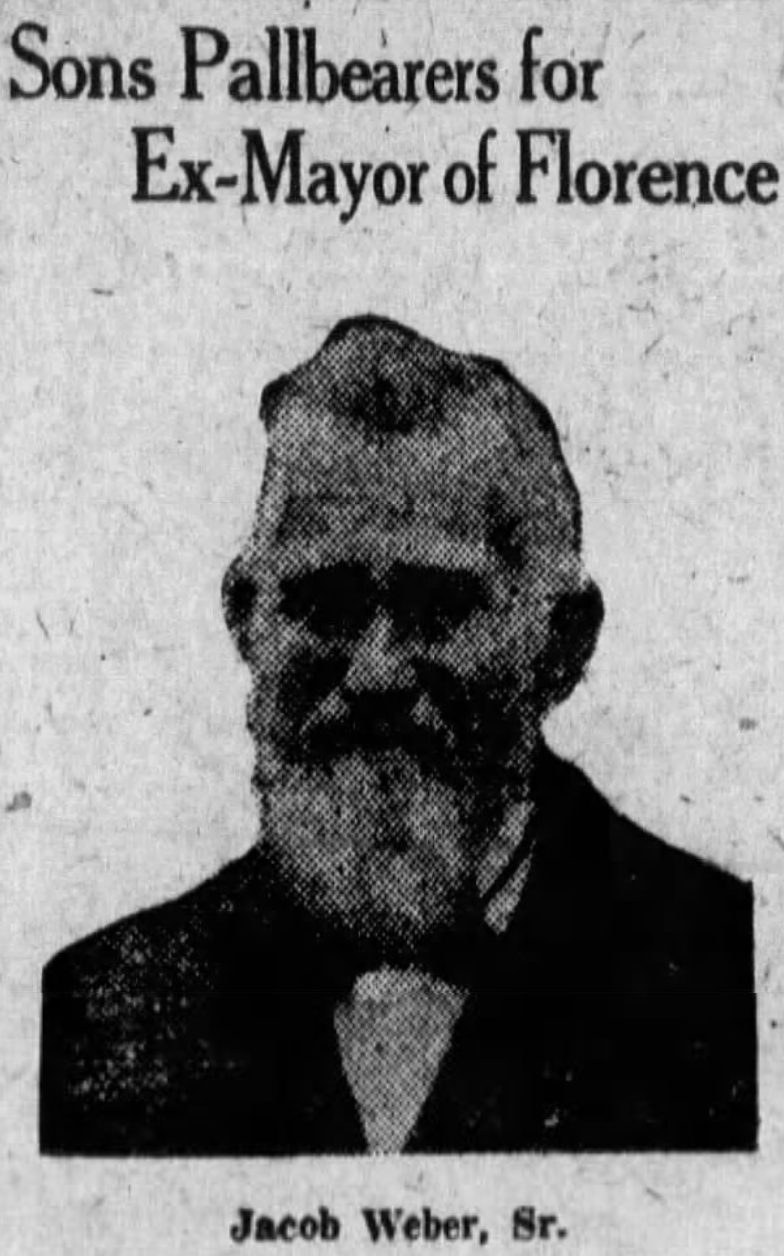

It was March 9, 1928, when the World-Herald reported the death of 64 year old Louie Ahko at Lord Lister Hospital at 26th and Dewey Street. Ahko fell sick at his Harney Street restaurant on Saturday and was taken to the hospital the next morning where he died soon after emergency surgery and a blood transfusion from his wife.

Ahko came to the United States in 1879 from Canton and worked “as a boy” in Seattle and Portland. He arrived in Omaha in 1890, the same year as Gin Ah Chin, and first worked as a cook for Phelan & Shirley’s construction company for a decade. In 1908, he first opened his cafe on Douglas Street. After the original Louie Ahko’s burned in the Hartman store fire and Ahko relocated to Harney.

The World-Herald called Ahko “probably the last of the well-known cafe men of Omaha” who was “known throughout the country” for “his meals, particularly his steaks” among “people of the stage who were his constant patrons when in Omaha.” Was it a Chinese immigrant who truly gave Omaha the reputation as the town where you could get a good steak?

Ahko had planned to leave the next month for a return trip back home to China. Instead, plans were made to return his body to burial in Canton following Presbyterian funeral service held at John Gentleman mortuary. About 50 people attended the service with the World-Herald noting that a third of them were Chinese. The newspaper also pointed out the large “wreath of lilies and roses” from the “Gee How Oak Tin association” although Ahko was not a member. The association still exists across the United States although it does not have a presence in Omaha.

With Ahko’s death, the newspaper noted the business was carried on by Frank Galloway and Edmund Blake, who’d both worked there for years and that Mrs. Ahko had returned the day after giving blood in an unsuccessful transfusion to save her husband.

At the End

In 1961, the World-Herald blamed the Great Depression on the end of Chinatown as the city’s Chinese community shrank to less than 100 people. It was said some “returned to the West Coast” and others went to Texas. That article also noted Omaha’s anti-fireworks law had a “quieting effect” on celebrating the Chinese New Year.

The On Leong Tong eventually removed to the “white-brick” building at 1518 Cass Street but the organization disbanded after death of its last member George Hay. That building later became distribution center for Volunteers of America and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2017. The old On Leong Tong building on North 12th Street was then “empty, isolated, condemned” and there were only an estimated 150 “Chinese-American” in Omaha, including “some recent immigrants.” At that time, 93 year old Chin Ah Gin then lived with his son Carl Chin and family at 3810 Corby Street. His descendants then included three daughters, three sons, 34 grandchildren, and 33 great-grandchildren. He died in 1962 at the age of 93.

It was in December 30, 1962 when the World-Herald reported the end of the On Leong Tong building at 111 North 12th. It would be erased from the cityscape within a month for a “parking lot for Campbell Soup”. According to the article, the building was “the center of Omaha’s Chinatown” with an “Oriental produce firm on the first floor.” After the tong moved to Cass Street, the building became “a flophouse, then a freight depot, then a warehouse” and still remains a parking today. Retired World-Herald reporter Florian Newbranch recalled the “mah jongg and other games” and a “shrine room with a squat Buddha.” There was also “the lottery, a complicated Chinese bingo” with “drawings every 10 minutes”. According to Newbranch, although “one supposedly could win five dollars to 10 thousand dollars” he never knew anyone who won “any more than the minimum”.

The World-Herald also quoted former Omaha police captain John Dennison who recalled a “survey” for the “gas company” when he saw “old Chinese ‘shooting the hip’ – lying on one hip and inhaling opium in bunks in the building.” It was likely Dennison who told the newspaper that somewhere in the building the murder of “a transient Chinaman named Charlie” was “planned” out of suspicion he belonged to the rival Hip Sing Tong.

The On Leong Tong still exists in some American cities but these days Omaha’s Chinatown isn’t even a memory for anyone who wanders around 12th and Dodge Streets. That neighborhood is different now. It was 1978 when Joseph and Alice Kuo opened the Great Wall chain of restaurants in Omaha as the first significant shift from the city’s long established Cantonese cuisine. According to the 2010 census, Omaha’s Chinese population was around 1,500 people. Today, King Fong’s still remains sadly closed and the city’s best Cantonese and culinary hint of Omaha’s long-gone Chinatown can now be found well west of 84th Street.

Self-Guided Tour of Omaha’s Chinatown

- First On Leong tong building, 111 North 12th Street

- Second On Leong tong building, 1518 Cass Street

- Office of Dr. C. Gee Woo, 519 N. 16th Street

- Mandarin Cafe, 1409 Douglas Street

- Bon Ton Restaurant, 203 S. 13th Street

- Joe Lee Residence, 714 South 17th Street

- Lee Wong Gem Residence, 114 North 12th Street

- Soon Lee Residence, 1617 Cass Street

- Sam Huey Residence, 1609 Cass Street

- Jimmy Chin Residence, North 16th and Burt Street

- Sing Hai Lo Company, 1306 Douglas Street

- Louie Ahko Restaurant, 1419 Douglas Street

- King Joy Cafe, 1412 Douglas Street

- Unique Cafe, aka The Elite Cafe

- Turf Cafe, 1306 Douglas Street

- Joe Lee’s Cafe, 1408 Farnam Street

- Nanking Restaurant, 1313 Douglas Street

- Peacock Inn Restaurant, 1814 Farnam Street

- Horseman Hotel, 1419 Dodge Street

- Bessie Woods residence, 11th and Leavenworth Streets

- King Fong’s, 315 South 16th Street

- Yingalongjingjohn and Yingyang Laundry, South 10th Street between Farnam and Harney Streets

- Hong Lee Laundry, Harney Street between 14th and 15th streets

- Omaha Chinese Christian Church, 4618 South 139th Street

- Louie Chas Chinese Laundry, 209 South 13th Street

- Lee Kune Chinese Laundry, 1610 Cass Street

- Lee Moy Chinese Laundry, 1514 Mike Fahey Street

- Fong Lao Laundry, 1514 Mike Fahey Street

You Might Like…

MY ARTICLES ABOUT THE HISTORY OF OMAHA’S NEAR NORTH SIDE

GROUPS: Black People | Jews and African Americans | Jews | Hungarians | Scandinavians | Chinese | Italians

EVENTS: Redlining | North Omaha Riots | Stone Soul Picnic | Native Omaha Days Festival

BUSINESSES: Club Harlem | Dreamland Ballroom | Omaha Star Office | 2621 North 16th Street | Calhoun Hotel | Warden Hotel | Willis Hotel | Broadview Hotel | Carter’s Cafe | Live Wire Cafe | Fair Deal Cafe | Metoyer’s BBQ | Skeet’s | Storz Brewery | 24th Street Dairy Queen | 1324 N. 24th St. | Ritz Theater | Alhambra Theater | 2410 Lake Street | Carver Savings and Loan Association | Blue Lion Center | 9 Center Variety Store | Bali-Hi Lounge

CHURCHES: St. John’s AME Church | Zion Baptist Church | Mt. Moriah Baptist Church | St. Philip Episcopal Church | St. Benedict Catholic Parish | Holy Family Catholic Church | Bethel AME Church | Cleaves Temple CME Church | North 24th Street Worship Center

HOMES: A History of | Logan Fontenelle Housing Projects | The Sherman | The Climmie | Ernie Chambers Court aka Strelow Apartments | Hillcrest Mansion | Governor Saunders Mansion | Memmen Apartments

SCHOOLS: Kellom | Lake | Long | Cass Street | Izard Street | Dodge Street

ORGANIZATIONS: Red Dot Athletic Club | Omaha Colored Baseball League | Omaha Rockets | YMCA | Midwest Athletic Club | Charles Street Bicycle Park | DePorres Club | NWCA | Elks Hall and Iroquois Lodge 92 | American Legion Post #30 | Bryant Resource Center | People’s Hospital | Bryant Center

NEIGHBORHOODS: Long School | Logan Fontenelle Projects | Kellom Heights | Conestoga | 24th and Lake | 20th and Lake | Charles Street Projects

INDIVIDUALS: Edwin Overall | Rev. Russel Taylor | Rev. Anna R. Woodbey | Rev. Dr. John Albert Williams | Rev. John Adams, Sr. | Dr. William W. Peebles | Dr. Craig Morris | Dr. John A. Singleton, DDS | Dr. Aaron M. McMillan | Mildred Brown | Dr. Marguerita Washington | Eugene Skinner | Dr. Matthew O. Ricketts | Helen Mahammitt | Cathy Hughes | Florentine Pinkston | Amos P. Scruggs | Nathaniel Hunter | Bertha Calloway

OTHER: 26th and Lake Streetcar Shop | Webster Telephone Exchange Building | Kellom Pool | Circus Grounds | Ak-Sar-Ben Den

Elsewhere Online

- For more information on Omaha efforts to oust the Manchu dynasty see: “A Revolutionary Meeting: Midwestern Chinese Plot to Overthrow Qing Dynasty” by Ryan Roenfeld for Omaha Magazine, April 3, 2018.

- “A Timeline of Chinese in Omaha” by Doug Meigs, Betty Chin and Bing Chen for Omaha Magazine on March 18, 2018.

- “Thick Chu Huey, owner of Chu’s Chop Suey House, dies at 84” by Blake Ursch for the Omaha World-Herald on Febrauary 21, 2019

- “Former hub for Omaha’s early Chinese community is recognized as historic place” by Blake Ursch for the Omaha World-Herald on Janurary 2, 2018.

- “Omaha’s Forgotten Chinatown (And the Continuation of Local Chinese Lunar New Year Celebrations)” by Doug Meigs for Omaha Magazine on February 23, 2018.

Bonus Pics!

Leave a comment