This article shares a history of interactions, circumstances, and other situations which distinctly marked the people, places, and events in Omaha in which African Americans and Jews shared history.

From the outset, Jews and African Americans were not treated as equal citizens in Omaha. Because of their racial identities, both groups were discriminated against and were not allowed to participate in economic, political, educational, and cultural life throughout the city. White supremacy, racism, intolerance and discrimination affected Black people and Jews in Omaha. Despite that, both Black people and Jewish people played an important role in Omaha’s development.

A lot has been made of the relationship between Omaha’s Jewish community and Omaha’s African American community. Perhaps the most succinct answer to “What is the relationship?” would be, “It’s complicated.” Whether it was Mayor Ed Zorinsky in the 1970s, the Central States Anti-Defamation League in the 1980s, or local journalist Leo Adam Biga in the 2000s, many people have said, implied, or otherwise tied together Black people and Jews in North Omaha.

Please share your additions, corrections or more information in the comments section.

Early History

Omaha’s history formally starts in 1854. Jewish people arrived within the next five years, and African Americans arrived the same year the new city was founded. Within ten years, both communities were growing earnestly but without acceptance from the white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant (WASP) majority of the city. The early history of Jews in Omaha was centered north of Dodge Street, which is my primary interest with this website. Similarly, the majority of the history of African Americans in Omaha happened north of Dodge, too.

In my research, I’ve found that for several decades both Jews and Black people faced discrimination in Omaha because of their identities. However, modern realities show that those identities did not change in identical ways. Instead, they went separate ways that are important to understand, not only for Omaha’s history, but for American history. The histories of African Americans and Jews are essential to everyone’s history, whether we identify as those groups or otherwise.

Within both these communities there are individuals and events that make poignant storytelling, deep learning, and deep connections within and among people of all identities. It all began with shared ghettoization, discrimination in many ways, and many other impacts of white supremacy.

Sharing Ghetto-ization

During the era from the 1860s through the early 1960s, much of the Near North Side neighborhood was co-inhabited by Jews and African Americans. Living next to each other, there was a particular kind of relationship between the two races. This meant that while Jews owned businesses throughout North Omaha, African Americans, who weren’t allowed to shop elsewhere, relied on those businesses for their goods and services. This has been called “symbiosis” by some authors; however, it was not a mutual exchange for the benefit of both communities.

Between approximately 1870 and approximately 1970, both African Americans and Jewish people had mutual interests in the Near North Side. However, they were affected differently. When Black people first arrived in Omaha, it was immediately before the Civil War and the Emancipation Proclamation. When Nebraska became a state in 1867, Black people in Omaha had been freed from slavery for three years. However, they were kept from the benefits of full citizenship by racism and white supremacy. Voting; securing home, business or personal loans; running for political office; participating in civic life in general; and other benefits of citizenship were kept far away from Black people in Omaha. As Jews arrived, they were kept from prosperity for a single generation. Within two decades there were successful Jewish business people in Omaha, and as wealth was accumulated more Jewish people had access to political office, major social influence, and other cultural, social, and economic benefits of being white.

Public spaces in the Near North Side neighborhood shared between African Americans and Jews included:

Often discriminated against and frequently the targets of racism, both African Americans and Jews were looked down upon and treated poorly by white people. Both groups made their own religious spaces too, which were sometimes the targets of racist actions, including arson and vandalism.

However, from the time they arrived through 1920, Jews accumulated opportunity and influence, and worked collectively to assure their peers’ successes, too. African Americans in Omaha attempted to do the same but weren’t able to benefit from white supremacy. Instead, laws and unspoken regulations controlled the contributions African Americans could make in early Omaha. This mean that generally speaking, Black people weren’t allowed to accumulate wealth, generate opportunities for their peers, or otherwise influence mainstream culture in the city.

Throughout this entire time, both Jews and Black people were afflicted by racist terrorists who threatened, beat, killed, and terrorized both populations in Omaha. However, the road diverged at a few key moments, including the 1891 lynching of George Smith when an African American man was pulled from the second Douglas County Courthouse jail and lynched by mob of 10,000 people; the 1919 lynching of Will Brown, when another African American man was pulled from the third Douglas County Courthouse jail and lynched by a mob of 20,000 people; and the subsequent wholesale abandonment of the Near North Side through white flight and benign neglect over the next 50 years.

Starting in the early 1920s, many of the businesses started, owned, and operated by Jews were eventually the only white-owned businesses left in the Near North Side neighborhood after white flight. There were accusations of discrimination against Black people by these businesses, including inferior products and services, inflated pricing, and other biases. However, some African Americans expressed gratitude at any businesses being left in the neighborhood. Between 1920 and 1945, many of the businesses along North 24th Street became Jewish owned and operated, while Black-owned businesses were often located in Jewish-owned buildings along the strip. The same held true for many of the houses in the Near North Side.

There were several organizations founded in Omaha as a result of the similar discrimination against Jews and Black people. Two of the Jewish economic organizing groups in the Near North Side included the Jewish Peddlers’ Protective & Benevolent Association and the Omaha Peddlers’ Union. Similarly for African Americans, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters had 90 members in Omaha, and there was an organization called the Colored Commercial Club in Omaha. The Negro Y.M.C.A. was established in Omaha in 1919 to provide a space for Black athletics and more; similarly, organizing to establish Omaha’s Jewish Community Center began in 1921.

This ghettoization was forced by white supremacy in Omaha. Rather than wearing white robes with matching hoods, white supremacists in Omaha operate within the economic, governmental, political, and educational systems throughout the city. This affected Jews and Black people similarly for many years, until it didn’t anymore. One of the first Jews to become permanent residents of Omaha was Aaron Cahn. Cahn began the assimilation process in Omaha by serving in the first Nebraska State Legislature in 1867. From that point onward, Omaha Jews continued gaining enough influence and power to exert their “white-ness” in order to assimilate into Omaha’s mainstream culture, and at that point their similarity to African Americans in the city ended; their ghettoization ended.

Despite similar attempts to accumulate political power, exert economic force, and overcome systemic racism, Black people in Omaha have not been able to escape white supremacy. Today, despite 160+ years of work to end their own ghettoization, the vast majority of African Americans in Omaha still live in North Omaha.

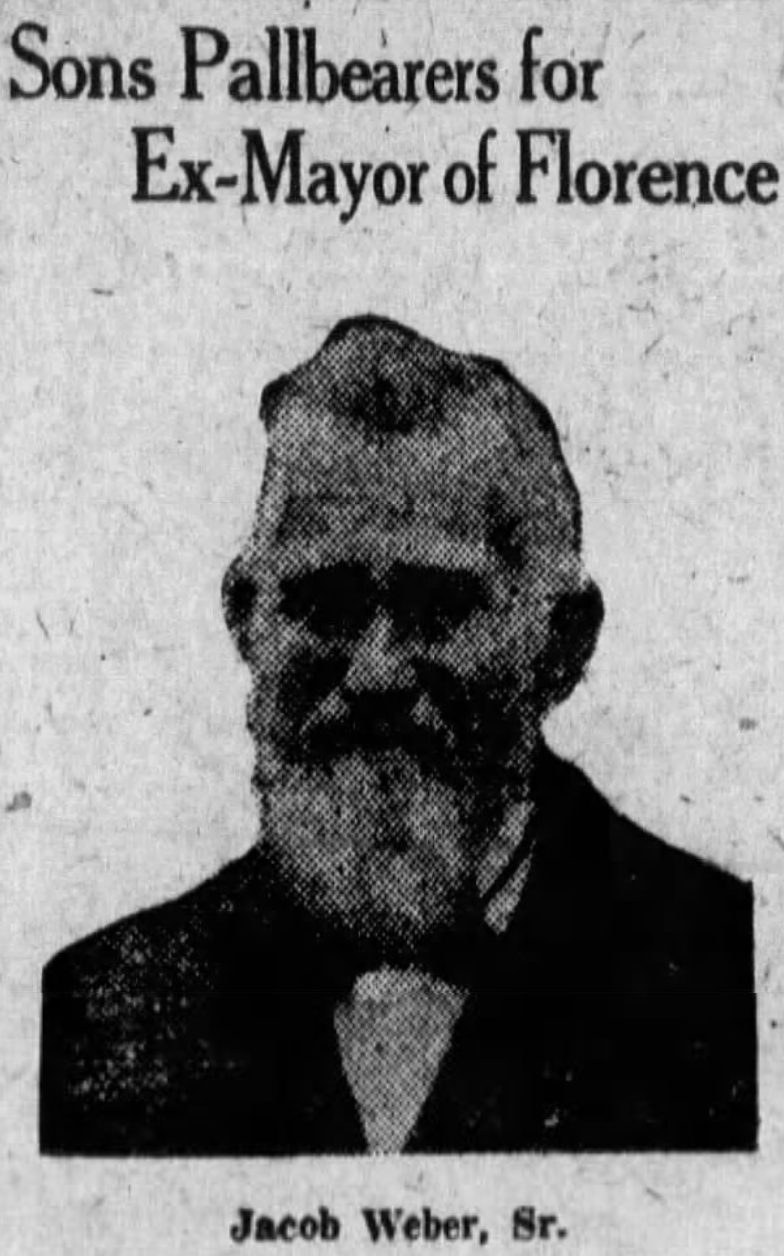

First Recorded Interactions

One of the first stories to emerge between Black people and Jews in Omaha comes from 1867. According to the Omaha Herald, on July 16, Edward Rosewater, the Jewish publisher of a major newspaper called the Omaha Bee, was attacked by a Black businessman named Dick Curry (18??-1883). Curry ran a saloon at 1705 North 24th Street, where Black people were segregated into the Near North Side. Rosewater wrote in the Bee that Curry’s business was “A squalid place of resort; a wretched dwelling place; a haunt; as a den of business…” Soon after, Curry found Rosewater walking on a street in downtown Omaha and beat him badly, with a historian saying that Rosewater “hovered above death for several days.” Curry was sentenced to four years in prison; Rosewater lived to write more later. More than one historian attributed this argument along racial lines.

While the Jewish community grew in influence and power, African Americans were thwarted at every turn of the junction economic, political, social, legal, and educational opportunities. Jews began buying buildings along North 24th Street and opening more and more businesses; were voted into political office and served civic roles; ensured laws, rules, and regulations didn’t work against them; built a bench of legal authority from the Legislature through the courts into the police force and with lawyers; and seized every chance to build the knowledge base of the community through formal and informal opportunities.

Throughout the entire history of the community, Jews and Black people were innately woven together in many aspects of the economics in the community. A Black Episcopalian minister who published a newspaper, the Rev. John Albert Williams of the Omaha Monitor regularly wrote against antisemitism in the city. Time would show that this Black-led, Black-focused Omaha newspaper wasn’t alone in calling out antisemitism either.

With Jews operating more than 200 stores of all kinds throughout the Near North Side between the 1880s and the 1960s, African Americans had places to shop and occasionally get jobs. For instance, there were many, many Jewish groceries throughout the area between Cuming Street and Ames Avenue from N. 16th to N. 36th, the extent of where Black people were allowed to shop. More than one African American elder’s oral history mentioned, “Finklestein’s Jew Store” and used other words as pejoratives to describe the relations between African Americans and Jewish people. Some of the other stores included:

- Cuming Market, 2820 Cuming St.

- Dave’s Market, 1404 N. 24th St.

- Evans Street Grocery, N. 16th and Evans St.

- Fannie’s Dairy Store, 1619 N. 24th St.

- Federal Market, 1414 N. 24th St.

- Garden Supermarket, Florence Blvd. and Emmet St.

- Meyerson Grocery, N. 24th and Maple St.

- Isadore Gilman Market, 2418 N. 18th St.

- H-K Specialty Company, 1609-11 Cuming St.

- Sam Hornstein Grocery, N. 28th and Binney St.

- Louis Market, N. 24th and Seward St.

- M. Nachman Grocery, 2011 N. 27th St. then 1401 N. 19th St. then 1445 N. 19th St. then 1441 N. 19th St.

- Plotkin Bros. Grocery, 2511-13 N. 24th St.

- Ratner Grocery, 1711 N. 24th St.

- Rosenblatt Store, N. 16th and Locust St.

- Shrago’s Grocery, 1802 N. 20th St.

- Sam Shiff’s Store, 1401 N. 19th St.

- Simon’s Grocery, N. 33rd and Lake St.

- Spar Grocers, 2023 Clark St.

- Spaulding Grocery, 2869 Spaulding St.

- Tuchman Grocery , N. 24th and Lake St. and N. 24th and Parker St. and N. 24th and Cuming Street and N. 16th and Yates St.

- Uncle Sam’s Market, 1404 N. 24th St.

- Wiesman Grocery, Florence Blvd. and Laird St.

- Witkin Store, 2202 N. 26th St.

There were several other businesses in North Omaha that Jews owned where Black people shopped, with many on North 24th Street. They included department stores, bakeries, shoe stores, liquor stores, and other stores, too.

It wasn’t easy for either immigrant Jews or formerly enslaved Black people in Omaha. The young city discriminated towards both communities and kept them segregated from mainstream white society, business, education, healthcare, and more for several decades. The interaction between the two populations was substantial though, and showed how there could be positive interactions. However, white supremacy still dominated in early Omaha.

“We always care for our own people.”

—A Jewish leader quoted in the Omaha Morning Bee, March 26, 1913

However, the biases between African Americans and Jewish people began early. For instance, when the massive March 23, 1913 tornado struck North Omaha, more than 100 people around the intersection of 24th and Lake Streets were killed. Instead of providing mutual relief and neighborly support, it appears that each population supported their own despite their physical proximity to each other. Photos show Black people gathered together for recovery operations and funeral processions, while newspaper reports detail how the Jewish community banded together to “support their own.” Stoked by racist writing in the Omaha World-Herald, there were competitions between Black people and Jews in the fields of entertainment and retail enterprises. However, the abilities of African Americans to compete were and continue to be hampered without a level playing field and equity between Jews and Black businesspeople.

The Roaring 20s and Beyond

One book observed that between 1900 and the 1940s, African Americans and Jews in Omaha had three places in the city where they interacted regularly:

- Near North Side Neighborhood: The informally segregated home to both populations, the Near North Side had homes, businesses, faith places, schools, and other shared spaces where Jews and Black people interacted regularly;

- Central High School: Opened as Omaha High School four decades earlier, Central High was the only public high school that allowed both Black and Jewish students to attend and graduate until the 1920s; and

- South Omaha Meatpacking Plants: While neither Jews nor Black people were allowed to work in the stockyards themselves, the meatpacking industry had Jewish owners involved and employed many Jewish and Black workers.

Both Black people and Jews became the targets of the Ku Klux Klan in Omaha in the 1920s. Through their hate literature and deep infiltration throughout Omaha society, the KKK sought to make African Americans and Jews appear less-than Protestant white people, and promoted disdain, hurt, and ultimately violence towards both groups. While the KKK was an obvious engine for prejudice during this era, it was already widely known that discrimination again Jews and Black people was wide-spread “among liberals, progressives, and radicals as well as conservatives and reactionaries” in Omaha during this time.

Additionally, the white supremacy that undergirds Omaha and American society at large became largely favorable towards the appearance of equality for Jews. This resulted in even more power and influence, ultimately facilitating white flight for Jews leading to the abandonment of the Near North Side in Omaha.

From the 1930s through the 1950s, the Jewish Press regularly addressed popular white supremacist messaging about apathy, ignorance, and inability among African Americans. The Omaha Star published articles supporting Jewish anti-racism and addressed injustices against Jews overseas leading up to World War II. Similarly, the Omaha Guide published articles highlight antisemitism, too.

After World War II, when white flight struck the area north of Lake and south of Sprague Street, Jewish investors reputably bought many of the houses in the area and rented them to Black people for the first time. While this was attributed as integration by some, others regarded it as price gouging and the beginning of absentee landlord-ing in the area, as most of the Jewish landlords lived outside North Omaha, and in a growing number of instances, out of Omaha.

By the early 1960s, many of the businesses, synagogues, longtime family homes, and other fixtures of the Jewish community in North Omaha were wholly left behind by Jewish residents, who moved to west Omaha neighborhoods where Jewish residents were ironically segregated from other white people.

At the same time though, the Omaha Star heralded Jewish involvement in the Civil Rights Movement nationally and shared several articles grappling specifically with relations between African Americans and Jews. After the 1950s, the Jewish Press newspaper echoed the Omaha Star by championing efforts among Jews to promote Civil Rights. This showed there were Jews who were aware of the injustices Black people continued facing and acknowledged them through words. One 1933 article protested the dismissal of an Alabama rabbi for anti-racist messaging to his congregation. It proclaimed, “Instead of discouraging our spiritual leaders from fighting for the downtrodden and oppressed, we should lend every public encouragement… We commend this leader of Israel who had the courage of his convictions and fought ardently and fearlessly for social vision in our handling of the negro cases in his territory.”

In a show of support for the Civil Rights Movement, in the 1950s many Jewish organizations issued proclamations and resolutions standing in support of African Americans. In a 1966 article from the Omaha Star, Rabbi Arthur J. Lelyveld was quoted about recent reports of a “Jewish backlash” because of Black antisemitism. The paper said he, “affirmed that, ‘I do not serve the cause of Negro emancipation because I expect the Negro to love me in return. The command to remember the stranger and the oppressed is unconditional.”

During that same era, by my best estimates there were fewer than a dozen Black-owned grocery stores in North Omaha, and by way of storytelling and news reports, few Jewish people shopped at those businesses. This disproportionate amount of business ownership for such an essential community business highlights the effects of white supremacy in North Omaha, even when Jews weren’t accepted into mainstream Omaha society.

Explosive Times

This is a collection of images showing the aftermath of riots in North Omaha between 1966 and 1969. Pics are courtesy of the Durham Museum and the author’s collection.

Relationships between Omaha’s Black community and Omaha’s Jewish community reached their absolute worst between 1966 and 1969. In that time frame, there were four distinct riot events in North Omaha, and during those events African Americans were accused of attacking, burning, looting, and otherwise destroying dozens of Jewish businesses and Jewish-owned buildings in the community.

However, before, during and after these events there were accusations by African American leaders and others within the community that Jews were profiteering, exploiting, and otherwise taking advantage of the Black community. In addition to complaints about the limited flow of money in African American homes due to business practices, some African Americans also claimed that Jewish homeowners were making “ghetto” living conditions worse for Black people through absentee landlord-ism and otherwise limiting opportunities for Black families to own homes in North Omaha. Simultaneously, there were accusations that Omaha’s first Jewish mayor, Johnny Rosenblatt (1907-1979), practiced racism in office. Serving from 1954 to 1961, Mayor Rosenblatt was noted as often making decisions that adversely affected African Americans, including launching thinly veiled “urban renewal programs,” but then also promoting the City of Omaha’s apparent tactic of benign neglect towards the Black community. In addition to those wide-reaching programs that demolished homes, wrecked streets, fluctuated public safety, and promoted police brutality, Rosenblatt’s policies and practices also seeped throughout other areas of City government, including parks and recreation, public works, public transportation, and job creation among others, explicitly maintaining historic racial segregation, poverty, and neglect. The effects of all of this peaked in the early 1960s. During that era Omaha’s Jim Crow became more obvious than ever before; coupled with the city’s burgeoning Civil Rights Movement, by 1966 North Omaha became a tinderbox of racial tension between white and Black people; and obviously between Jews and Black people.

It’s time that we stop doing things ‘for’ the Negro and start doing things ‘with’ him.”

Norman Hahn, director of the Omaha Human Relations Board

The tensions within the traditional Jewish neighborhood and the now-predominantly Black community exploded in the summer of 1966. The first so-called “race riot” in Omaha happened on July 4, 1966. It was sweltering hot that day, and in the evening a group of African Americans had gathered at the intersection of 24th and Lake. Surrounding that busy intersection were a number of businesses owned by Jews and others, including grocery stores, liquor stores, jazz clubs, and more. Several historians have noted that the absence of recreational activities for young people in the surrounding neighborhood and the ongoing blighting of the area by city leaders led to the first brick being thrown through a business’s window. Whatever the cause, it led to three days of riots throughout the Near North Side that decimated a number of empty storefronts and active businesses, many with Jewish owners. The Nebraska National Guard was called in to stop the rioting. In its aftermath more than two dozen businesses between Cuming Street and Lake Street reportedly closed immediately. Many more closed in the months after.

Making common the experiences of Jews and Black people nationwide, in 1966 an article run in the Omaha Star suggested that “both Negroes and Jews are both the puppets and victims of ideas which the Christian West announced and did not mean.” Seeking to explain the rioting nationwide, the author promoted an idea of the American Christian hegemony over society and how its decimating every community that doesn’t identify that way, particularly Jewish and Black people. Calling for unity among these two groups, he suggests “…if Negroes can ‘join’ society through anti-Semitism, Jews can ‘join’ it as Whites.”

In October 1966, Norman Hahn said “It’s time that we stop doing things ‘for’ the Negro and start doing things ‘with’ him.” Hahn, director of the Omaha Human Relations Board, was speaking to a reporter with the Jewish Press. Hahn called for Jews to volunteer with the Urban League and other organizations, and also said, “We must make our voices heard, our concern must be visible. We must be active in our opposition to all forms of segregation, discrimination and exploitation of our Negro neighbors.”

Also in October of that year, the regional director of the Anti-Defamation League gave a talk called “The Omaha Jew and the Omaha Negro.” However, the contents of this presentation weren’t published. In the months afterward, the Jewish Press included several articles about the riot, including one that summarizing rumors that African American “agitators” came from Kansas City, Des Moines, Sioux City, and beyond. The regional ADL director quipped, “Agitators must be getting a mileage allowance this year!” In that same edition, the ADL director also noted that “Mayor Sorenson reportedly said that ‘If a Negro has the money, he can buy a home any place in Omaha.’ This is good news. For a while I really thought we were going to have some difficulty achieving citywide open housing. Wait until the Real Estate Board hears about this!”

Mayor Sorenson reportedly said that ‘If a Negro has the money, he can buy a home any place in Omaha.’ This is good news. For a while I really thought we were going to have some difficulty achieving citywide open housing. Wait until the Real Estate Board hears about this!

Arthur Teitelbaum, Regional ADL Director, November 4, 1966

Between 1966 and the end of 1969, there were four major riot events in the Near North Side along with dozens of smaller skirmishes before and afterwards. Longstanding historic Jewish-owned businesses in North Omaha closed during those years, including Ritz Theater; Ideal Furniture and Ideal Hardware, 2524 North 24th Street; Forbes Bakery, 2711 North 24th Street; Bernstein Groceries and Meats, 4901 North 16th Street; Marks Kosher Market, 1804 North 20th Street; and several other businesses. Each of these Jewish-owned businesses and many others were demolished by the riots.

Not all Jewish-owned businesses blamed the riots for closing during this time period. Instead, it was just a convenient time. In 1983, Near North Side grocer Sid Feldman made such a claim. Feldman said the riots were probably on his mind to some extent when he decided to sell his grocery store in 1968.

“But that wasn’t the main reason,” he said. “When you’re in the grocery business, the store owns you. You don’t have time for anything else. You don’t really live. I just decided it was time to get out.”

Sid Feldman as quoted by the Omaha World-Herald, October 15, 1983

The city continued wrestling with racism though, and Jews were among those struggling to make sense of it all.

In 1969, Omaha Central High School held a panel for students to ask five African American and Jewish women from Omaha about social issues. There were two Black women and three white women, including a Jewish woman. A student asked about relationships between African Americans and Jews, and the Jewish panelist replied, “Jews have been very clannish and that’s not to our credit.” This self-awareness was echoed at that event and again over the next 50 years.

Over the years, Omaha Star coverage focused on Black-Jewish politics several times, including 1984 when they featured the topic. Covering Jesse Jackson’s historic campaign for president, the paper suggested that Black politicians supported many Jewish issues to challenge the media’s portrayal of a widening gap between Black and Jewish politics. Citing several specific policy issues, the paper also laid out some cultural exchanges happening on the national level to make their case.

One African American political actor in Omaha, Eddie Staton, said in 1987 that the high point of Black and Jewish relations in Omaha came in the 1970s “when the Anti-Defamation League actively assisted in implementing the busing program.”

Black Jews in Omaha

For at least 115 years, Black Jews have been treated as sensational, exceptional, and otherwise phenomenal in Omaha. Although it took more than a century to officially acknowledge, there have been Black people in the city who identified as Jews for a long time. According to one 1980s story in the Omaha Star, most African American Jews at that point were Orthodox.

In 1903, the Omaha World-Herald reported the shocking “discovery” of a “tribe of Black Jews” by an Englishman exploring Australia. This sensationalist reporting exploited the conclusions of this white man in order to make Omahans interested in world affairs. However, it was later shown that the report was false, and nothing was said again in the paper for a few years.

Highlighting the writing of Omaha’s preeminent Black historian George Wells Parker (1882-1931), in 1908 the newspaper printed his account of Black Jews around the world. Parker was using the point to emphasize that “it is to the mixed descent of the Jew that his accomplishments are due. They are after all a truly wonderful people… I shall say at least that were it not for the dark strain which courses through their veins, they could never have given to the world the long list of geniuses whose names emblazon the scrolls of history.”

It made the news when Temple Israel hosted an international scholar in 1915 who came to Omaha to talk about Ethiopian Jews called Falash Mura. The paper continued treating the existence of Black Jews as a strange and sensational phenomenon to engage its readers, reporting stories of the “strange” Ethiopian Jews facing Mussolini’s Italian invasion during World War II, and the existence of India’s Chocin Jews in 1951. The newspaper featured a story of a Black Jews who left the United States to move to Liberia in 1966. After being deported from there in 1969, Israel welcomed them and they moved there. The subject of Ethiopian Jews kept being addressed in Omaha, and in 1981 an expert on the people, Dr. Graenum Berger, spoke at the Jewish Community Center about them. The Great Plains Black History Museum featured art by Ethiopian Jews in 1986.

In 1971, the media in Omaha featured a story about Rabbi Hailu Mosha Paris of New York City. Rabbi Paris, a Black Jew, spoke at Beth Israel about Black/Jew relations in the United States. He said “Black antisemitism is not that much of a Black vs. Jew conflict as it is a Black vs. white struggle.” Reporting that there were “about 40,000 Black Jews in the United States,” the rabbi said conflicts between Jews and Blacks extended from the disproportionate number of retail businesses Jews owned in Black neighborhoods across the nation. He also acknowledged that “Jews have been among the very best white supporters of the Civil Rights movement,” but that “economic friction” had caused some decline in support.

Highlighting a 50+ year old synagogue for African American Jews in Harlem, in 1977 the Omaha Star featured a story on Rabbi David Dore, the leader there. The second-ever Black student to graduate from Yeshiva University in NYC, Rabbi Dore served more than 300 members at his synagogue. However, falling prey to the sensationalization of Judaism among African Americans, the Omaha Star made no point of identifying Black Jews in Omaha or even commenting on how Judaism was doing in Omaha at that point.

Rev. Dr. James Thomas was the leader of the Calvin Memorial Presbyterian Church on North 24th Street in the 1970s. In 1979, the Omaha World-Herald interviewed him about the interrelated role of the Black church and Black history in Omaha. During that interview, Thomas suggested acknowledged there were Black Jews in Omaha, saying their history is part of the history of the Black church in the city. This was the first published acknowledgment of Black Jews in Omaha.

In the 1980s, the Omaha Star shared several stories about African American Jewish people. For instance, they told about a Black Jew in California who was rallying the Jewish community to fight sickle cell anemia, which almost plagues Black people more than any other race. Another story featured the story of a 13-year-old African American girl’s Bat Mitzvah at a Reform synagogue in North Carolina. That year, the newsletter of the Central Conference of American Rabbis said the event was “perhaps the first Black Jewish Bat Mitzvah in the South, perhaps the nation.”

Dinah Abrahamson (1954-2013) was an African American from Omaha who led one of the few Black families associated with the Jewish Chabad Lubavitch movement. In 1993, Abrahamson and her two sons joined the Hasidic Jewish dynasty, becoming one of the few Hasidic families in Omaha. An active member of the Nebraska Republican Party, she and her family eventually moved to Brooklyn where they lived in a neighborhood with both Hasidic Jews and African Americans.

Senator Chambers and the Jewish Community

Throughout his career, the longest-ever Nebraska State Senator Ernie Chambers, an African American, was regularly implicated as having antisemitic viewpoints. In 1984, he was quoted by the Omaha World-Herald as saying there are differences between Jews and blacks that “cannot be made to go away through attempts to stifle exposure and discussion of them.” He went on to say, “If you think there are not significant, widespread examples of Jewish discrimination and racism against black people in this country, I will provide you with information regarding companies, corporations, clubs, industries… with heavy Jewish influence if not outright control which display the worst type of racism against black people.” That year, the Anti-Defamation League condemned Senator Chambers in a letter which said, “The anti-Jewish bigotry of Ernie Chambers has no place in a democratic, pluralistic society which is tolerant of all its minorities, be they black, Jewish or Hispanic.” From that point on, Senator Chambers was frequently accused of “demagoguery and bigoted speech” among other offenses against Jews.

In 1986, the Plains States region of the ADL released a 13-page report called “Ernest Chambers: Profile in Extremism.” According to the Omaha World-Herald in 1987, the City of Omaha Human Relations Director Eddie Staton said the report hurt relations between Jews and Black people. “It’s the general feeling in the black community that the report was unnecessary and the report wasn’t only an attack on Sen. Chambers but the black community itself.” Staton called a meeting to reduce tension between the communities. Along with Black and Jewish leaders, there were members of the Black-Jewish Dialogue of the National Conference of Christians and Jews present. According to the World-Herald, “Staton said the main reason he wants to bring the Black leaders together is to draw attention to existing local groups that have been working for better Black and Jewish relations.” Senator Chambers was quoted as saying, “People think that since the Jewish community didn’t disavow the report that it reflects the Jewish community’s opinion. I know there are a lot of black people angry and disgusted at the report.” The Jewish Press reported that Jewish groups met over the issue too, with a meeting in March 1987 on the subject of “The Black/Jewish Reaction to the ADL Report on Senator Ernie Chambers.”

Friction between Senator Chambers and the Jewish community continued through the rest of his career. His own statements clearly showed large-scale antisemitic perspectives, but were regularly defended as just and otherwise necessary assessments. His role as a representative of Omaha’s African American community was rarely questioned again after the 1987 issues, either.

“Jews need us in this community, because if there were no black people, white people would be on these Jews just like the Nazis were. We’re the buffer, and Jews know it.”

State Sen. Ernie Chambers (1995)

In a 2004 article from the Nebraska Life magazine, Senator Chambers was labelled as an “anti-Catholic, anti-Semitic, racist state senator who hates America” by a religious rights leader. Ernie went on to say he was “branded Anti-Semitic by the jaundiced gentleman because I highlight, ceaselessly castigate and resist white degredations against non-white people… thereby projecting onto me the demon which inhabits and possesses his own morally barren soul.”

Chambers went on to have other comments he made labeled as antisemitic throughout his career, too, all the way to 2020 when he was forced from office by term limits.

Modern Disparities

In 2010, the Census reported that Omaha was 77.47% white, and 12.32% African American. In 2021, the Jewish Federation of Omaha website said there are 8,880 Jews in Omaha.

When Civil Rights leader and former Senator Julian Bond (1940-2015) spoke in Omaha in 1984, he said “Blacks and Jews were allies in the early battle for Civil Rights, but the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 were the last great alliance between the Jews and the Blacks.” His observation didn’t fall on deaf ears, but little came of the comment. Speaking forthrightly, Senator Bond said it was important to remember “There are blacks who don’t like Jews and Jews who don’t like blacks, and we shouldn’t try to change them.” He also called for regular face-to-face conversations instead of back-and-forth exchanges in the media.

In 1985, Jews in Omaha joined a national campaign to improve Black-Jewish relationships. There were annual dialogues, meetings, and learning events for several years specific to these efforts.

Part of the work of the Tri-Faith Initiative today is to confront racism and build inclusiveness. Started in the mid-2000s, the Tri-Faith Initiative is a project of Muslims, Jews and Christians with new worship spaces and an interfaith center all located adjacent to each other in the same complex. Very unique in Omaha, this type of space is rare worldwide. While not addressing race specifically on their website, the unspoken implication seems to be that the diversity, equity and inclusion sought after among faith groups is also applicable among people of different races.

In the last few years, these works have taken new forms and had new efforts by Jews in Omaha. For instance, the Ruby Platt Allyship Initiative (RPAI) was a response to a pointedly white supremacist interaction between a person of color within the Jewish community of Omaha. Seeking to address the heinousness of the event, the RPAI has secured community and institutional partners, provided anti-bias workshops for Jewish leaders, conducted a community-wide anti-bias training, and created a curriculum for Jewish students to learn about bias and allyship. In December 2021 the Anti-Defamation League of the Plains States will bring me to Omaha as part of the Ruby Platt Allyship Initiative for a several day program to explore white supremacy through history and the present as well.

Relations between Black people and Jews in Omaha are complicated today, and have been complicated since the city was founded more than 165 years ago. Maybe by exploring that past openly and examining it today we can move forward into new spaces in the future. There are few physical spaces in Omaha today for African Americans and Jews to specifically explore the past through action, talk, work, thought, and healing together, separately, or as one.

Please share your questions, concerns, considerations, and otherwise in the comments section.

You Might Like…

- A History of Jews in North Omaha

- A History of Racism in Omaha

- A History of Antisemitism in Omaha

- A Tour of the Civil Rights Movement in Omaha

MY ARTICLES ABOUT THE HISTORY OF OMAHA’S NEAR NORTH SIDE

GROUPS: Black People | Jews and African Americans | Jews | Hungarians | Scandinavians | Chinese | Italians

EVENTS: Redlining | North Omaha Riots | Stone Soul Picnic | Native Omaha Days Festival

BUSINESSES: Club Harlem | Dreamland Ballroom | Omaha Star Office | 2621 North 16th Street | Calhoun Hotel | Warden Hotel | Willis Hotel | Broadview Hotel | Carter’s Cafe | Live Wire Cafe | Fair Deal Cafe | Metoyer’s BBQ | Skeet’s | Storz Brewery | 24th Street Dairy Queen | 1324 N. 24th St. | Ritz Theater | Alhambra Theater | 2410 Lake Street | Carver Savings and Loan Association | Blue Lion Center | 9 Center Variety Store | Bali-Hi Lounge

CHURCHES: St. John’s AME Church | Zion Baptist Church | Mt. Moriah Baptist Church | St. Philip Episcopal Church | St. Benedict Catholic Parish | Holy Family Catholic Church | Bethel AME Church | Cleaves Temple CME Church | North 24th Street Worship Center

HOMES: A History of | Logan Fontenelle Housing Projects | The Sherman | The Climmie | Ernie Chambers Court aka Strelow Apartments | Hillcrest Mansion | Governor Saunders Mansion | Memmen Apartments

SCHOOLS: Kellom | Lake | Long | Cass Street | Izard Street | Dodge Street

ORGANIZATIONS: Red Dot Athletic Club | Omaha Colored Baseball League | Omaha Rockets | YMCA | Midwest Athletic Club | Charles Street Bicycle Park | DePorres Club | NWCA | Elks Hall and Iroquois Lodge 92 | American Legion Post #30 | Bryant Resource Center | People’s Hospital | Bryant Center

NEIGHBORHOODS: Long School | Logan Fontenelle Projects | Kellom Heights | Conestoga | 24th and Lake | 20th and Lake | Charles Street Projects

INDIVIDUALS: Edwin Overall | Rev. Russel Taylor | Rev. Anna R. Woodbey | Rev. Dr. John Albert Williams | Rev. John Adams, Sr. | Dr. William W. Peebles | Dr. Craig Morris | Dr. John A. Singleton, DDS | Dr. Aaron M. McMillan | Mildred Brown | Dr. Marguerita Washington | Eugene Skinner | Dr. Matthew O. Ricketts | Helen Mahammitt | Cathy Hughes | Florentine Pinkston | Amos P. Scruggs | Nathaniel Hunter | Bertha Calloway

OTHER: 26th and Lake Streetcar Shop | Webster Telephone Exchange Building | Kellom Pool | Circus Grounds | Ak-Sar-Ben Den

Elsewhere Online

- “Unraveling White Supremacy with Adam Fletcher Sasse,” official website of the Anti-Defamation League of the Plains States

- Anti-Defamation League – Plains States/CRC official website

- Ruby Platt Allyship Initiative official webpage

- African-American and Jewish Collaboration and Conflict Oral History Interviews from University of Nebraska at Omaha Archives and Special Collections

Bonus Images!

Sources (in no order)

- Omaha World-Herald Digital Archives

- Omaha Star Digital Archives

- Jewish Press archives

- Howard Chudacoff (1972) Mobile Americans: Residential and social mobility in Omaha, 1880-1920. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Carol Gendler (1968) “The Jews of Omaha: The first sixty years The Jews of Omaha: The first sixty years.” University of Nebraska at Omaha.

- Nathan Bernstein (1908) “The Story of the Omaha Jews,” Reform Advocate.

- The Jews of Omaha: The first sixty years by Carol Gendler for the University of Nebraska at Omaha on March 1, 1968.

- The Jewish Foundation. “The History of Jewish Omaha“

- Pollak, O. B. (2011) “The Jewish Peddlers of Omaha,” Nebraska History 63 (1982): 474-501.

- “OMAHA: Douglas and Sarpy Counties“. International Jewish Cemetery Project, International Association of Jewish Genealogical Societies.

- Alder, C. and Szold, H. (1919) American Jewish Year Book 5680, Volume 21. American Jewish Society.

- Postal, B. and Koppman, L. (1954) A Jewish Tourist’s Guide to the U.S. Jewish Publication Society of America.

- Nebraska Jewish Historical Society (October 1995) Newsletter.

- Beth Hamadrosh Cemetery – Graveyards of Omaha website.

- Grossman, A. (April 1984) “North 24th – ‘Street of Dreams‘”, Newsletter 11, 1. Nebraska Jewish Historical Society.

- Pollak, O. B. (2001) Jewish Life in Omaha and Lincoln: A Photographic History. Arcadia Publishing.

- “Congregation of Israel First permanent Jewish House of Worship in Nebraska” by Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation

- Ella Fleischman Auerbach (1927) “A Record of Jewish Settlement in Nebraska,” Nebraska State Historical Society.

- Ira M. Sheskin (2017) The 2017 Jewish Federation of Omaha Population Study:A Portrait of the Omaha Jewish Community. Jewish Federation of Omaha.

- “When Omaha’s North 24th Street brought together Jews and Blacks in a melting pot marketplace” by Leo Adam Biga in 2010.

Leave a comment