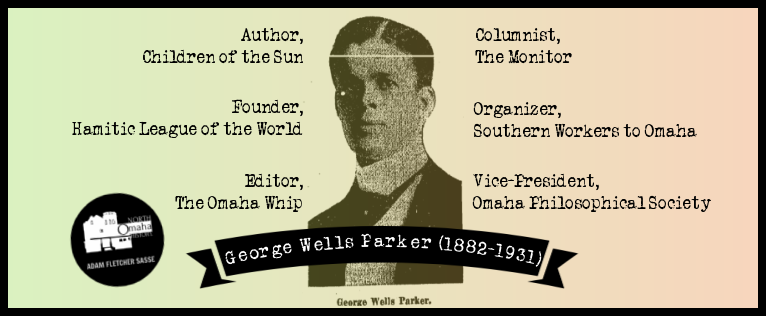

In the early 20th century, one philosophical history writer moved mountains in the minds of African Americans nationwide. In addition to writing hundreds of articles, starting an organization, and leading Omahans to higher thinking, this writer also exposed the effects of the KKK nationally, possibly costing him his career. His writing, journalism and activism left an indelible mark on Black studies still felt today; however, a lot of his work has been largely forgotten. This is a biography of North Omaha’s George Wells Parker (1882-1931).

Being Young in Omaha

George was born to Abraham W. Parker (1856-1916) and his wife out of state in 1882. When he was young, his family moved to the Near North Side where his father worked for the Union Pacific Railroad. Young George probably attended the Izard Street School before going to Omaha High School in the 1890s. His sisters were Leonna and Emma, and his brothers were Ray and Lawrence.

Around 1896, Parker left Omaha for Howard University in Washington, D.C. and studied there for a few years. He left Howard and worked in D.C. as a mail clerk for the United States Postal Service. After a few years, he came back to Omaha and worked as a mail clerk at the Post Office. Later, he studied medicine at Creighton University.

Between approximately 1907 and 1915, Parker was an insurance salesman, operating an office from his home to sell house insurance and health insurance.

Becoming a Journalist

Parker started writing as a young man, and won a competition at the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition in Omaha in 1898. Competing in the Expo’s national competition for high school and college writers, Parker was lauded for the style and argument in his debate paper. He was the winner of the entire event. Even from this young age, Parker’s history writing focused on Africa as the cradle of civilization and promoted Africans as the greatest of all races in the world.

Frequently writing editorials and guest essays, he won second place in a local real estate-oriented essay content sponsored by the Omaha World-Herald in 1911. Other articles by Parker were published in Black newspapers and mainstream newspapers throughout the western United States during this era of his life. He was also published in several academic journals, including The Forum, The Literary Digest, and The Voice of the Negro.

While beginning his career, Parker was very active throughout the community. Before starting his position as the vice-president of the Omaha Philosophical Society in 1910, in 1904 he was secretary of the Douglas County Colored Men’s Roosevelt and Webster Club. This group wanted the liberal Republican Party to focus on civil rights for African Americans. In the late 1910s he was also an active member of the Omaha chapter of the NAACP. In 1921, he was the founding secretary of the North Side YMCA.

Rev. Dr. John Albert Williams founded The Omaha Monitor, a Black newspaper for the community, in 1915. Two years later in 1917 he hired George Wells Parker as a columnist. Parker had often written letters to The Monitor to refute articles by Rev. Williams, especially when it came to history. His family were also longtime members of Rev. Williams’ church, St. Philip Episcopal. However, Parker wrote prolifically for The Monitor for several years, and it served as a launching board for other activities too.

Hamitic League of the World

In 1917, George Wells Park founded the Hamitic League of the World, an Afrocentric community building organization. Based on Parker’s historical analysis, the League’s name was based on Ham, the son of Noah in the Old Testament of the Bible. In 1918, the Hamitic League started publishing a journal called The Crusader. Parker was pen pals with its editor Cyril Briggs, and never actually met him in person. When the League stopped publishing the journal, it continued as the journal of Briggs’ new organization called the African Blood Brotherhood.

The goal of the Hamitic League of the World was to,

“inspire the Negro with new hopes; to make him openly proud of his race and of its Great contributions to the religious development and civilization of mankind and to place in the hands of every race man and woman and child the facts which support the League’s claim that the NEGRO RACE IS THE GREATEST RACE THE W ORLD HAS EVER KNOWN.”

In 1918, the Hamitic League published an important pamphlet written by Parker called Children of the Sun. Referred to more recently as a “racial vindicationalist,” Parker’s most popular work was said to objectively blend propaganda and scholarship.

In Children of the Sun, George Wells Parker offered a short analysis of the history of the African continent, Black culture, and its broad influences throughout the entire world. He promoted archeology and evidence that African academics and cultures were more advanced than Europe, Asia, and elsewhere, and laid out a compelling argument to re-establish the entire historical cannon to reflect this reality.

After just a year, the Hamitic League of the World folded. It’s role was largely taken over by the African Blood Brotherhood, an NYC-based organization promoting Afrocentrism.

Later Newspaper Career

We found him a virtual storehouse of knowledge on the race question, especially Black history. His major objective in life was apparently to refute the prevalent racist lies and to build Black dignity and pride. He possessed wide knowledge and seemed to have read everything.

—Harry Haywood in A Black Communist in the Freedom Struggle: The Life of Harry Haywood (2012)

In 1921, after a dispute with Rev. Williams, George Wells Parker left The Monitor. Soon after, lawyer Harrison J. Pinkett hired Parker to be editor of a Black newspaper called The New Era, founded in 1920. Mrs. Jessie Hale-Moss was his assistant editor. However, Parker and Pinkett fought constantly about politics and the positioning of the paper within Omaha’s African American community. Parker wanted more radical politics and an Afro-centric position, and since Pinkett didn’t want to go in that direction, Parker quit. The New Era stayed in publication into 1926.

“…one of the foremost authorities in the race on Egyptology and Assyriology, and a profane student of early African culture…”

United States Congress House Special Committee on Communist Activities in the United States (1930)

It was just a year later in 1921 when George Wells Parker established a paper called The Omaha Whip. Parker accused Pinkett of associating with the Omaha’s Ku Klux Klan and calling on Omahans to support Mayor James C. Dahlman and the rest of Dennison’s machine. However, The Omaha Whip only printed two editions and then disappeared. No copies of the paper are known to exist today.

He contributed the information he was going to publish in The Omaha Whip to several papers nationally, including the New York World, which published an expose. It was noted in The Monitor for the publication. Other newspapers the expose was published in included the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Boston Globe, Pittsburgh Sun, Cleveland Plain Dealer, the Seattle Times, among several others.

However, after publishing his newspaper against the KKK and perhaps alienating his ally Rev. Williams, his career in Omaha was largely over in spring 1921, and shortly afterward he moved to Chicago where his brother lived.

Later Life

In 1925, the West Virginia Collegiate Institute presented a pageant called “The Children of the Sun” at their university based on Parker’s book. Featuring the HBCU’s large band, orchestra and glee clubs, the event was a collaboration between Parker and Clarence Cameron White, a nationally known African American violinist. Parker wrote the scenes and dances, and White orchestrated the entire event.

George Wells Parker was the keynote speaker at the last session of the American Negro Labor Conference (ANLC) in 1925. The ANLC was established in 1925 by the Communist Party as a vehicle for advancing the rights of African-Americans, sharing communism within the Black community, and recruiting African-American members for the party. He speech was noted for focusing on Black history, hitting at racism and encouraging Black confidence and pride.

“It was five or six weeks ago that I learned of the American Negro Labor Congress. When I read the article by William Green, president of the American Federation of Labor, warning the Negro to stay away from this congress because he said it was directly connected with the Soviets of Russia, the moment I read the article I became interested in the congress. There was a time when they said freedom was bad for the Negro. They also said education was bad for the Negro. They said association with whites was bad for the Negro. No matter what the Negro wants, what he desires, it is a bad thing for the Negro. So when Mr. Green said this congress was a bad thing for the Negro, I became interested.”

George Wells Parker, 1925 ANLC Conference

Then, Parker highlighted the relationship between African Americans and the Ku Klux Klan. He hammered on the need for Black people to pay attention to the Klan by emphasizing the damning effects of the organization. He drove into the issue by saying, “The Klan is not dying. The Klan is going ahead by leaps and bounds. I receive at my desk fifteen different Klan papers. They are organizing chapters in every hamlet and town. They have set 1935 as the year when they shall take government. ”

Prescribing the need to dismantle the KKK psychologically, Parker finished his speech by calling for Black people to learn about themselves and to “rid himself of the inferiority complex which he suffers.” He also called upon African Americans to rally together and struggle against white supremacy and the KKK.

Mental Health Struggles

Throughout his life, Parker wrestled with mental health in a variety of ways. In 1905, he committed to the Nebraska State Hospital for the Insane in Lincoln, when he came back to Omaha from Howard University. The basis of that event was detailed in a March 12, 1905 feature in the Omaha World-Herald called “Remarkable story of brilliant young Negro author.” Highlighting his education and accomplishments to that point, the article said his parents were saddened by their son’s inability to stay mentally stable. After he was committed, a collection of essays written as a book manuscript he’d sent to Doubleday and Page Publishers was returned at his parents’ request “as they have fears for the consistency of the closing chapters.” Although his parents committed to submitting the manuscript later, the book entitled Because was never published. It was never mentioned again after 1905.

In 1911, Parker was arrested for murdering a woman in St. Paul, Minnesota. While he was staying there with a fiancé named Marguerite de Tienne, she postponed their wedding indefinitely, telling Parker her that the woman who ran the boarding house where she lived encouraged her to call off the wedding. Parker went on a rampage and kicked everyone out of the house. He wildly attacked Marguerite’s house mother, cutting her more than 40 times until she was dead. Soon after the killing, Parker was sentenced to an insane asylum in Minnesota. However, his father Abraham and the family’s minister, Rev. John Albert Williams took the train to Minnesota and were able to bring Parker back to Omaha.

He published nothing between 1911 and 1916, and that year his writing publishing started appearing again.

Death and Legacy

After 1925, there is no record of Parker speaking or writing again.

George Wells Parker died in 1931 at age 49. His sister went to Chicago to escort her brother’s body back to Omaha, where Rev. Williams led the funeral. Parker was buried in Forest Lawn Cemetery in an unmarked grave.

Parker was an important voice for Black pride, self-determination and Afrocentrism in North Omaha in a period when the Near North Side was extremely segregated, Omaha was extremely racist and the city plainly didn’t want to change. He was the founder of the Hamitic League of the World; a leader of the Omaha Philosophical Society; writer for The Monitor, editor of The Omaha Whip, and author of Children of the Sun.

In 2021, a group of history activists bought a grave marker for Wells’ burial site at Forest Lawn Cemetery.

Special thanks to Nicholas Paine and Charles Klinetobe for their contributions to my research.

You Might Like…

- The Life of Rev. Dr. John Albert Williams

- Community Leaders in North Omaha

- Black Newspapers in Omaha

Elsewhere Online

- George Wells Parker on Wikipedia

- “History Finally Catches Up with Brilliant Black Activist from Omaha George Wells Parker” by Leo Adam Biga for NOISE

- “George Wells Parker” on findagrave.com

BONUS IMAGES

Leave a comment