When Omaha was established in 1856, white supremacists were determined to enable enslavement in the new Nebraska Territory. Taking roles as elected officials and public servants, these racists worked against Black freedom through the government. This is a history of laws enforcing racial discrimination in Omaha between 1854 and 1899.

Before 1854: Laws that Defined Settlement

My research shows that before 1899, there were a lot of local, county and state policy choices directed at disenfranchising, disempowering or otherwise incapacitating Black people in Omaha. These rules affected education, law enforcement, firefighting, voting, public health and more.

Beginning before there was even a Nebraska Territory, in 1820 the US Congress passed the Missouri Compromise stating that the land which became Nebraska was not supposed to allow enslavement in its borders.

Thirty years later, Congress renegotiated the compromise with Republicans acquiescing to Democrats to create the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which let residents of the new territory decide whether to allow slavery.

Feelings against this were strong and a campaign called the Anti-Nebraska Movement spread across the country, locking the nation’s cultural sentiment towards the state into place before it ever formally existed. The Anti-Nebraska Movement wanted to ensure enslavement was legal in what was going to become a future state, but failed when the new territory was allowed to vote on whether to become a state that allowed enslavement.

1854 to 1867: Enforcing Racial Discrimination

The territorial period in Nebraska saw the formation of a legislature, the creation of the Omaha City Council, the election of the first Omaha mayor, and the hiring of the first superintendent of the Omaha school district.

Black people have been in Omaha since its establishment in 1854, marking the beginning of the continuous growth of Omaha’s Black population since. Since its founding, there has never been a decade-over-decade decrease in Omaha’s Black population.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 baked ambiguity about enslavement into the Nebraska Territory. However, white supremacists worked immediately to codify racism in the territory. For this time period, its important to remember that the Nebraska Territorial capital was in Omaha, and all of the legislators in session would come to the city, living in Scriptown and otherwise make their worldviews known to Black people, white people and anyone else who would listen.

The first known policy affecting Black Omahans codified by the first session of the Nebraska Territory Legislature happened in 1854 when territorial legislators passed the Nebraska Organic Act, which limited voting to “free white males” only.

Given the tension of the Kansas-Nebraska Act over whether slavery should exist in the territory, it should come as no surprise that there were disagreements over whether or not there was slavery in Nebraska. However, from 1855 forward they have raged. Nebraska City legislator William H. Taylor said in 1855, “the fact is indisputable. African slavery does practically exist in Nebraska. Our eyes can not deceive us, and if slavery is wrong, morally, socially, or politically, it is wrong to hold one slave. There is no distinction in principle between holding one human being in bondage and ten thousand.” Between 1854 and 1867, Taylor proposed anti-slavery legislation several times.

Two years later in 1856, the Legislature blatantly discriminated against Black children when passing a law that said, “It shall be the duties of the directors… to take… an enumeration of all the unmarried white youths… between the ages of five and twenty-one years… for the purpose of affording the advantage of free education to all the white youth of this territory…”

The policy-driven discrimination against Black people in Omaha continued, but not without attempts to stop it. For instance, in 1858, a legislator from Nemaha County named Samuel Gordon Daily (1823-1866) introduced a bill in Nebraska’s territorial legislature “to abolish slavery in the territory of Nebraska.”

Not every territorial legislator was an enslaver or sympathizer. When a territorial legislator from Otoe County named William H. Taylor (1827-1865) introduced the first bill to end slavery in Nebraska in 1859, Omaha legislator Dr. George Miller (1830–1920) protested, effectively stopping the bill from moving forward. But Taylor built awareness.

I have found that despite what’s traditionally been said, in the era before 1861, there were at least 50 enslaved people in Nebraska, including at least a few in Omaha. In the 1890s, one historian wrote, “It is not generally known, but it is a fact, that there were from 1856 to 1858 more slaves in Nebraska than in Kansas…” (Minick 1898, 76)

A so-called “colored school” was open in Omaha and served at least twenty-seven students annually from 1865 to 1872. The Nebraska Legislature enacted a statute in 1865 declaring marriage between whites and a Negro or mulatto, also called miscegenation, was illegal. They made it a misdemeanor with a fine up to $100, or imprisonment in the county jail up to six months, or both. That same year, historical figure J. Sterling Morton (1832-1902) wrote, “It will be more manly to accept negro suffrage by legal enforcement than to humiliate ourselves by its voluntary adoption as the price of admission to the Union… We take n—-r only when forced to it by Congress and therefore are for remaining at present a territory.”

In 1867, Nebraska only ratified its anti-enslavement law after the president pressured them to. He prohibited Nebraska from becoming a state before then because it wouldn’t pass an anti-enslavement law. Before 1867, there were no fewer than five attempts to pass a bill stopping enslavement in the territory, and even then it only happened after the Legislature overturned the governor’s veto of the bill. In order to become a state, the policy of the state was required to change. On March 1, 1867, Nebraska became the 37th state in the Union.

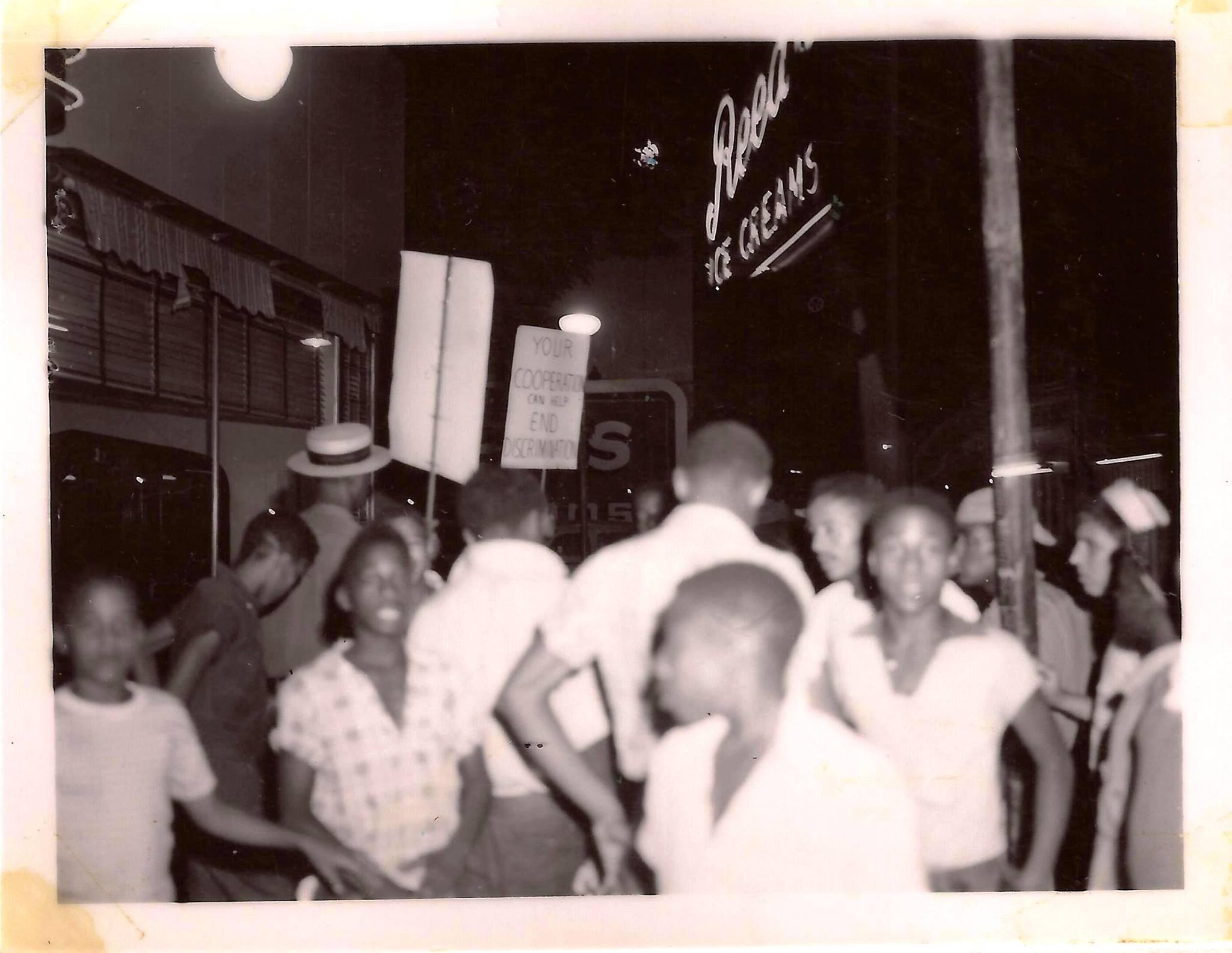

That positive development was immediately obscured by white supremacist terrorism though when, on March 4, 1867, a mob of “400 armed Democratic roughs” used revolvers to drive away twenty African American voters from the local polls. The Omaha mayor, the Douglas County sheriff and the Omaha police force refused to protect their right to vote. While the terrorism was vile, the absolute political enabling of the disenfranchisement was purely despicable.

It didn’t stop there, and in a debate on the floor of the Legislature about Black students in public schools later the same year, one legislator was recorded as saying, “But the amendment proposed by the majority of the committee contemplates the admission of colored children to our schools on an equal footing with the white youth. This is reaching too far in advance of the age. The people of Nebraska are not yet ready to send white boys and white girls to school to sit on the same seats with negroes; they are not yet ready to endorse in this tacit manner the dogma of miscegenation; especially are they yet far from ready to degrade their offspring to a level with so inferior a race.”

1869 to 1889: Bucking the Trends

Some of the developments of this next time period were coincidental, some were deliberate, and a few were almost inexplicable. By 1869, the federal Reconstruction program was well underway and the lives of Black people were changing: for the first time, African Americans could vote, own property, receive an education, legally marry and sign contracts, file lawsuits, and even hold political office.

In one of the first positive developments of this era in Nebraska history, in 1869 the United States government hired the first African American in Nebraska to hold a government job. Omaha’s Edwin Overall, an Underground Railroad conductor from Chicago, was appointed (hired) as a mailman for the post office and the balance of power was different. This may have influenced the government hiring dynamic in Omaha by acknowledging African Americans were eligible for positions they were previously denied.

Soon after that hiring in 1870, Richard Curry became the first African Americans person nominated for Omaha City Council. Although he did not win, he did succeed in generating interest within the Black community for political office in Omaha.

Protests at the Omaha Board of Education led by Edwin Overall brought to the closure of the “colored school” run by the city in 1871. The campaign took two years, including testimony from Black parents. In addition to closing the Jim Crow school, it led to Black students being integrated into several public schools in the eastern portion of the city. This is the first recorded instance of west Omaha being racially segregated from the eastern segments of the city. At the time, “west Omaha” started around 33rd Street. The board report is the first recorded codification of racial discrimination in Omaha I have found data for.

The first African American woman to graduate from Omaha High School was Edwin Overall’s daughter, Ida Overall (1860-1925) in 1879. Soon afterward, Miss Overall completed normal school and applied to the Omaha school board to be a teacher. However, the school board turned her away because they didn’t hire Black teachers. Along with her sister Victoria (1867-1918), she moved to Kansas City and became a teacher there.

In 1880, the Omaha Police Department hired its first African American police officer, Frank Bellamy. He served until 1886. The next year, 1887, was the first recorded police brutality against a Black person in Omaha was the death of Georgiana “Georgie” Clark (18??-1887) while in custody. Her death was explained away in the local newspapers.

“No colored man need apply,” announced an 1882 job announcement in the Omaha Daily Herald newspaper. The Herald, which was started by racist Southern sympathizer Dr. George Miller, ran this type of ad regularly for decades, indicating not only its own adherence to racial discrimination but also to Omaha’s acceptance for the same. While this wasn’t government policy, it shows it was accepted business practice in Omaha that reinforced the reality of de facto segregation along with de jure segregation.

1889 to 1899: The New Black Power

In the last decade of the 19th century, African Americans faced triumphs and terror. Advances in professional life, law enforcement and democratic representation were outstanding, while white supremacy continued its overwhelming terrorism.

The year 1889 saw several important developments. That year, Omahan Silas Robbins (1857-1914) became the first African American to be admitted to the bar in Nebraska. The first trial for police brutality in Omaha happened in 1889 when a Black performer named James A. Smith (18??-1899) was killed by an Omaha police officer while in custody. A jury acquitted the police officer. Also in 1889, Claus Hubbard (1852-1907) of Omaha became the first recorded Black candidate for office in Nebraska, running for legislature in 1889. He lost.

The US Census of 1890 showed a major population jump in Nebraska in the prior decade. A decade earlier in 1880, 811 Black residents lived in Omaha making up 2.7% of the city’s population of 30,518 residents. By 1890, Omaha had 4,658 Black residents who comprised 3.3% of the city’s 140,452 residents. This was the first of three major Black population leaps in Omaha’s history. The first African American candidate for state office was Rev. George Woodbey (1854-1937) of Omaha, who ran for Lieutenant Governor of Nebraska for the Nebraska Prohibition Party in 1890 and lost. That same year, Edwin Overall became the first African American candidate for the Nebraska State Legislature. He lost. Also in 1890, the first proposal for pensions for formerly enslaved people was made to the US Congress by a Republican representative from Omaha. The bill, H.R. 11119, had been lobbied for by the formerly enslaved, their family members and friends, and was proposed by William Connell (1846-1924). It did not pass.

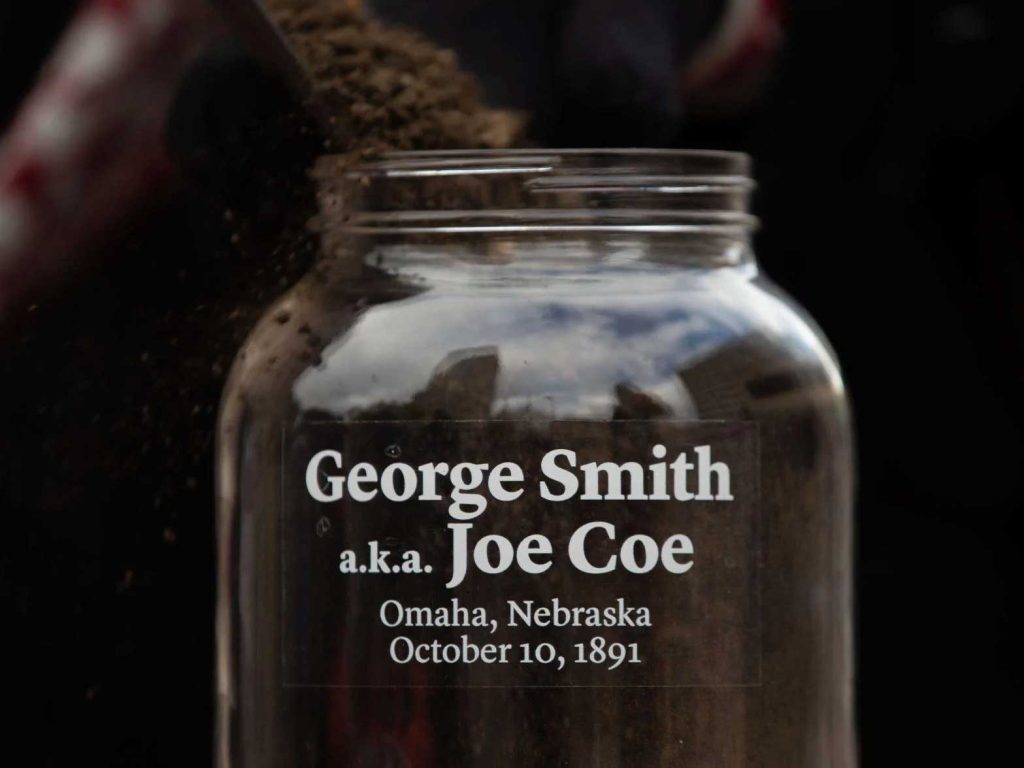

The first recorded lynching of an African American man in Omaha happened in 1891 when George Smith, a laborer, was accused of raping a white girl. When a mob of 10,000 people gathered outside the Douglas County Courthouse and demanded him, the city’s elected leadership, the police chief and the county sheriff all pled incapable of dealing with the horde. They rioted, broke into the jail and stole George Smith, lynching him from nearby telegram cables. The incident eerily predates the more well-known lynching of Will Brown 28 years later.

In 1892, Dr. Matthew Ricketts became the first African American to be elected to the Nebraska Legislature. One of the first identified pieces of evidence of racial segregation in Omaha housing emerged this year when a newspaper began running advertisements for houses

The first civil rights law for the State of Nebraska, Nebraska Statutes Section 4000, Chapter 10, was adopted by the Nebraska Legislature in 1893. The law states, “Civil rights of persons: All persons within the state shall be entitled to a full and equal enjoyment of the accommodations, advantages, facilities and privileges of inns, restaurants, public conveyances, barber shops, theaters and other places of amusement, subject only to the conditions and limitations established by law and applicable alike to every person.” The same law said, “A civil right is a right accorded to every member of a district, community or nation.”

Civil rights of persons: All persons within the state shall be entitled to a full and equal enjoyment of the accommodations, advantages, facilities and privileges of inns, restaurants, public conveyances, barber shops, theaters and other places of amusement, subject only to the conditions and limitations established by law and applicable alike to every person… A civil right is a right accorded to every member of a district, community or nation.

—State of Nebraska, Nebraska Statutes Section 4000, Chapter 10, was adopted by the Nebraska Legislature in 1893

There were changes in business practices throughout this decade. Cudahy Packing Plant in South Omaha hired the first known Black firefighter in Nebraska history, William Mitchell, in 1893. Throughout the decade, several industries including the railroads, meatpackers and the smelting company hired large groups of African American laborers from the South as strikebreakers. While this had negative implications in some respects and was cited as a cause of rioting more than once, it also increased Omaha’s Black population and made jobs previously unavailable to Black people more available.

Two years later, in 1895, Rev. Annie R. Woodbey of Omaha became the first African American woman nominated for political office in Nebraska when she was nominated for the University of Nebraska Board of Regents by the Prohibition Party. She did not get the seat.

In his time in the Nebraska Legislature, Dr. Matthew Ricketts successfully advocated for several bills. 1895 was a banner year for him, as he got Nebraska’s first age of consent for marriage passed , and the repeal of the state’s miscegenation statute. While the latter was later reinstated, the former still stands. That same year, Dr. Ricketts also successfully advocates for the establishment of a Black fire station in Omaha to serve a nearby Black neighborhood. The first Black firefighters were hired by the Omaha Fire Department to work at Hose Company #11. The company was comprised of Captain Samuel G. Ernest, Lieutenant Joseph R. Henderson, Scott Jackson, Everett W. Watts, Harry W. Black, and Plumer Walker.

Omaha’s Lucy Gamble (1875-1958) became the first African-American teacher in Omaha Public Schools in 1895, teaching until 1901 when she got married. She taught at the Dodge School. The same year, in 1895, Millard Singleton (1859-1939) was named the first African American Justice of the Peace in Nebraska, serving the Eighth Ward in Omaha.

In 1896, Cyrus D. Bell (1848-1925), publisher of the Afro-American Sentinel newspaper in Omaha, surveyed Omaha businesses for racial discrimination under the premise of preparing a guide for Black visitors to the forthcoming Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition of 1898. Publishing his findings in several editions of his newspaper, The Afro-American Sentinel, Bell was surprised at the ambiguity of most business’ responses. While he did find some instances of overt racism, many businesses—including hotels, restaurants, barbers and stores—claimed each instance was situational.

Millard Singleton was elected as the first Black constable in Omaha in 1897.

1898 saw the city fixate on an enormous event called the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition, held in North Omaha. There were several developments affecting Black people throughout the Expo, which was like a world’s fair. For instance, Clarence “Cap” Wigington (1883-1967) was 15-years-old when he made an art presentation at the Expo, where he was awarded three first prizes in the art competitions and won a medal for his works. He became one of the nation’s leading civic architects in another city. Similarly, one of the next era’s cultural icons, George Wells Parker (1882-1931), won an award at the Expo too.

These developments and many others opened the doors to the evolution of Omaha’s Black community, which became especially obvious two decades later during the Harlem Renaissance in North Omaha. In the meantime and afterward though, laws defeating Black empowerment, challenging Black excellence and demeaning African Americans continued and continue to be enacted throughout the city.

After the First 40+ Years

In the decades after Omaha was settled, history shows the city’s leaders were determined to ensure white supremacy throughout their functions. This article shows how nearly every sector in Omaha had codified Jim Crow, including businesses, policing, education, housing, and several other areas. It also shows a distinct pattern of de jure segregation, which is segregation that is imposed by law, instead of the de facto segregation that is often attributed to the city.

There is little talk of reparations for African Americans in Omaha today, and people who share that idea are regarded as extremists. Education in Omaha Public Schools does not highlight the realities I examine here, and while many African American families share anecdotal stories about laws enforcing discrimination in early Omaha, few know specifically what happened.

In the future, perhaps white Omaha can face its history by becoming conscious about what’s happened. The Omaha City Council, the Omaha School Board and the Douglas County Commissioners and other elected bodies could fess up and encourage other elected officials to do the same, including the Omaha mayor and the Nebraska governor, as well as the Nebraska Legislature.

More than a monument, these facts need to be taught in schools, shared through the media, and otherwise be made know as historical facts. Until then, I’ll keep highlighting what I can, when I can, how I can. How about you?

Special thanks to Anthony Ashby for inspiring this article!

You Might Like…

MY ARTICLES ABOUT BLACK HISTORY IN OMAHA

MAIN TOPICS: Black Heritage Sites | Black Churches | Black Hotels | Segregated Hospitals | Segregated Schools | Black Businesses | Black Politics | Black Newspapers | Black Firefighters | Black Policeman | Black Women | Black Legislators | Black Firsts | Social Clubs | Military Service Members | Sports

PIONEER BLACK OMAHA: Black People in Omaha Before 1850 | The First Black Neighborhood | Black Voting in Omaha Before 1870 | Racist Laws Before 1900 |

EVENTS: Stone Soul Picnic | Native Omahans Day | Congress of Black and White Americans | Harlem Renaissance in North Omaha

RELATED: Race and Racism | Civil Rights Movement | Police Brutality | Redlining

NEBRASKA BLACK HISTORY: Enslavement in Nebraska | Underground Railroad in Nebraska | Grand Island |

TIMELINES: Racism | Black Politics | Civil Rights | The Last 25 Years

RESOURCES: Book: #OmahaBlackHistory: African American People, Places and Events from the History of Omaha, Nebraska | Bibliography: Omaha Black History Bibliography | Video: “OmahaBlackHistory 1804 to 1930” | Podcast: “Celebrating Black History in Omaha”

MY ARTICLES ABOUT CIVIL RIGHTS IN OMAHA

General: History of Racism | Timeline of Racism

Events: Juneteenth | Malcolm X Day | Congress of White and Colored Americans | George Smith Lynching | Will Brown Lynching | North Omaha Riots | Vivian Strong Murder | Jack Johnson Riot | Omaha Bus Boycott (1952-1954)

Issues: African American Firsts in Omaha | Police Brutality | North Omaha African American Legislators | North Omaha Community Leaders | Segregated Schools | Segregated Hospitals | Segregated Hotels | Segregated Sports | Segregated Businesses | Segregated Churches | Redlining | African American Police | African American Firefighters | Lead Poisoning

People: Rev. Dr. John Albert Williams | Edwin Overall | Harrison J. Pinkett | Vic Walker | Joseph Carr | Rev. Russel Taylor | Dr. Craig Morris | Mildred Brown | Dr. John Singleton | Ernie Chambers | Malcolm X | Dr. Wesley Jones | S. E. Gilbert | Fred Conley |

Organizations: Omaha Colored Commercial Club | Omaha NAACP | Omaha Urban League | 4CL (Citizens Coordinating Committee for Civil Rights) | DePorres Club | Omaha Black Panthers | City Interracial Committee | Providence Hospital | American Legion | Elks Club | Prince Hall Masons | BANTU | Tomorrow’s World Club |

Related: Black History | African American Firsts | A Time for Burning | Omaha KKK | Committee of 5,000

Leave a Reply