The history of African American politics in Omaha started after the Civil War in the 1860s and has fluctuated a lot since then. There has been an ongoing fight for fundamental rights to voting, political representation, and civic power since, and the struggle is far from over today.

Early Decades

Before Omaha was even became a city in 1854, Black people were affecting and affected by politics in the future city. The history of Black political activism in Omaha between 1854 and 1899 represents the pioneer phase of the community’s leadership, a period defined by the transition from territorial exclusion to the establishment of a sophisticated professional class. During these forty-five years, Black Omahans laid the spiritual, journalistic, and fraternal foundations that allowed them to navigate a city that was often hostile to their presence.

The era began with the city’s incorporation in 1854, but for the first decade, Black political life was primarily a battle for basic legal personhood. The Nebraska Territorial Constitution of 1854 originally restricted voting to free white males, a clause that actually delayed Nebraska’s entry into the Union until 1867. During this time, the population was small but politically resilient, with early settlers like Sally Bayne establishing a presence long before the end of the Civil War. Immediately following the war, the arrival of veterans like Richard D. Curry in 1865 transformed the community. In 1868, Curry organized the Negro Republican Club, aligning the community with the Party of Lincoln. However, the Betrayal of 1870, when white Republicans rejected Curry’s nomination for Alderman in favor of a white candidate, triggered the first organized calls for independent voting. Leaders like John Lewis urged Black citizens to act as a swing vote to force concessions from both parties, a strategy of selective patronage that would become a staple of Omaha activism.

As the population grew to nearly 800 by 1880, the focus shifted to state-level influence through the Colored Conventions Movement. This was a national effort to coordinate political strategy, and Omaha served as the hub for Nebraska, Kansas, and other states in the Midwest.

Spiritual power was anchored by St. John’s AME Church and Zion Baptist Church, which served as the primary meeting halls for political strategy. These churches provided a sanctuary where political and spiritual liberation were discussed as one. Fraternal networks also played a crucial role; Curry founded the first Black Masons lodge in 1868, and Dr. W. H. C. Stephenson brought medical and spiritual leadership from Nevada in the late 1870s, organizing the State Convention of Colored Americans in 1880. These lodges and conventions created a structured leadership hierarchy that could mobilize the community quickly. Edwin R. Overall, a former Underground Railroad conductor and wealthy real estate investor, used his position in the Knights of Labor to argue that Black political power was inseparable from labor rights and home ownership. He was one of the first to recognize that without property and job security, voting rights were precarious.

The final decade of the 19th century was the golden age of the early Black elite in Omaha. By this point, the community was no longer just reacting to white politics; it was actively shaping Nebraska law. In 1892, Dr. Matthew Oliver Ricketts was elected to the Nebraska State Legislature. He was a master of parliamentary law and successfully pushed for the state’s first civil rights protections and the legalization of interracial marriage. Ricketts proved that a Black man could govern effectively in a state that was nearly 98% white.

During this time, Omaha became a hub for Black journalism, with three major newspapers representing competing ideologies. This press war ensured that the community was never a monolith. Ferdinand L. Barnett founded a newspaper called The Progress as a radical, anti-compromise voice; George F. Franklin and Thomas Mahammitt operated The Enterprise as a pragmatic, pro-business outlet; and Cyrus D. Bell established the Afro-American Sentinel as an independent Democratic voice.

By 1899, Black Omaha was led by a council of leaders who were often rivals but collaborated on major legal and social crises. This group included Millard F. Singleton, who built a dynasty in civil service as a Justice of the Peace and a storekeeper for the IRS, and Vic Walker, a lawyer and former Buffalo Soldier who navigated the city’s complex machine politics. In the mid-1890s, this council worked together to exonerate George Washington Davis, a Black man they believed was being used as a scapegoat for a train disaster. This coordination between the press, the law, and the legislature showed that Omaha had a fully functioning, professionalized Black political machine before the turn of the century.

The period concluded with a sense of rising prominence as the community successfully fought for representation at the 1898 Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition. By ensuring that Black contributions to the West were recognized on a world stage, these pioneers cemented their place in the city’s identity. This foundation proved essential when the 20th century brought the challenges of the Great Migration and the trauma of the 1919 riot; the community already possessed the newspapers, churches, and political experience required to defend its interests and preserve its identity in the face of escalating segregation.

The First Half of the 20th Century

The period between 1950 and 1999 in Omaha, Nebraska, was defined by a transition from grassroots civil rights activism to the establishment of formal political power. Following the post-war industrial boom, the city’s Black community found itself physically and economically confined by redlining and segregation, yet it utilized this concentration to build one of the most sophisticated political machines in the American West.

The 1950s were characterized by the rise of “direct action” led by a new generation of activists who were no longer content with slow, institutional negotiation. The DePorres Club, an interracial group founded at Creighton University, became the vanguard of this era. Their most significant victory was the Omaha Bus Boycott of 1952–1954. Orchestrated in coordination with Mildred Brown and the Omaha Star, the boycott targeted the Omaha and Council Bluffs Street Railway Company. By urging citizens to use eighteen pennies for fare—a protest that jammed the company’s counting machines—they successfully forced the transit system to end its discriminatory hiring practices and employ Black drivers. This victory predated the Montgomery Bus Boycott and proved that economic withdrawal was a viable political tool in the North.

As the 1960s began, the political landscape shifted toward a struggle for structural reform in housing and education. In 1963, the Citizens Coordinating Committee for Civil Liberties, or 4CL, emerged as a coalition of Black ministers and community leaders. They organized massive rallies and “sing-ins” at the City Council to demand fair housing ordinances. However, the slow response of the white political establishment led to a growing rift between the “Old Guard” ministers and a more radicalized youth. This radicalism was fueled by the 1966 Oscar-nominated documentary A Time for Burning, which exposed the deep-seated racial prejudices of Omaha’s white churches. The mid-to-late 1960s were marred by four major riots, largely centered on North 24th Street. These uprisings were often triggered by police brutality, most notably the 1969 killing of fourteen-year-old Vivian Strong by a police officer. These events left the historic business district in ruins and accelerated “white flight” to West Omaha, further isolating the Black community geographically.

The 1970s marked the transition from protest to the statehouse. In 1970, Ernie Chambers, a barber and law school graduate who had gained fame for his fiery testimony in A Time for Burning, was elected to the Nebraska State Legislature. Chambers would go on to serve as the singular, most dominant voice in Nebraska’s Black politics for the next four decades. His 1971 entry into the Unicameral coincided with a period of intense legal friction, specifically the Rice/Poindexter case. The 1970 bombing that killed an Omaha police officer led to the conviction of Black Panther leaders David Rice (Mondo we Langa) and Ed Poindexter. Throughout the 1970s, the community rallied behind the “Omaha Two,” asserting that the trial was a political frame-up orchestrated by the FBI’s COINTELPRO. This case became a permanent fixture of Black political discourse in the city, representing the adversarial relationship between North Omaha and the judicial system.

The 1980s brought a significant shift in municipal representation. For nearly a century, Omaha’s “at-large” election system had effectively shut Black candidates out of the City Council, as they could not overcome the majority white vote citywide. Activists pushed for a move to district-based elections, which was finally achieved in 1981. This change immediately bore fruit with the election of Fred Conley, who became the first African American on the City Council since the 1890s. Conley’s tenure (1981–1989) allowed for the first time a direct legislative focus on the infrastructure and economic needs of North Omaha. This period also saw the rising influence of Brenda Council, who served on the Omaha School Board before joining the City Council. Council became a symbol of a new, professionalized Black political class that was capable of building broad coalitions.

The final decade of the century, the 1990s, was an era of both significant breakthroughs and persistent barriers. In 1992, Carol Woods Harris became the first African American elected to the Douglas County Board of Commissioners. However, the most high-profile political event of the decade was Brenda Council’s 1997 mayoral campaign. Running against incumbent Hal Daub, Council built a historic coalition that nearly broke the executive glass ceiling. She lost by a mere 700 votes—a result that both devastated and inspired the community. The 1990s ended with the demolition of the Logan Fontenelle housing projects in 1996 and the end of court-ordered busing in 1999, events that signaled a “return to neighborhood schools” and a new, more complex era of de facto segregation. By the end of 1999, the foundation had been laid for the 21st-century breakthroughs, as leaders like John Ewing Jr. and a younger generation of activists prepared to take the mantle from the titans of the civil rights era.

The Second Half of the 20th Century

The period between 1950 and 1999 in Omaha, Nebraska, was defined by a transition from grassroots civil rights activism to the establishment of formal political power. Following the post-war industrial boom, the city’s Black community found itself physically and economically confined by redlining and segregation, yet it utilized this concentration to build one of the most sophisticated political machines in the American West.

The 1950s were characterized by the rise of “direct action” led by a new generation of activists who were no longer content with slow, institutional negotiation. The DePorres Club, an interracial group founded at Creighton University, became the vanguard of this era. Their most significant victory was the Omaha Bus Boycott of 1952–1954. Orchestrated in coordination with Mildred Brown and the Omaha Star, the boycott targeted the Omaha and Council Bluffs Street Railway Company. By urging citizens to use eighteen pennies for fare—a protest that jammed the company’s counting machines—they successfully forced the transit system to end its discriminatory hiring practices and employ Black drivers. This victory predated the Montgomery Bus Boycott and proved that economic withdrawal was a viable political tool in the North.

As the 1960s began, the political landscape shifted toward a struggle for structural reform in housing and education. In 1963, the Citizens Coordinating Committee for Civil Liberties, or 4CL, emerged as a coalition of Black ministers and community leaders. They organized massive rallies and “sing-ins” at the City Council to demand fair housing ordinances. However, the slow response of the white political establishment led to a growing rift between the “Old Guard” ministers and a more radicalized youth. This radicalism was fueled by the 1966 Oscar-nominated documentary A Time for Burning, which exposed the deep-seated racial prejudices of Omaha’s white churches. The mid-to-late 1960s were marred by four major riots, largely centered on North 24th Street. These uprisings were often triggered by police brutality, most notably the 1969 killing of fourteen-year-old Vivian Strong by a police officer. These events left the historic business district in ruins and accelerated “white flight” to West Omaha, further isolating the Black community geographically.

The 1970s marked the transition from protest to the statehouse. In 1970, Ernie Chambers, a barber and law school graduate who had gained fame for his fiery testimony in A Time for Burning, was elected to the Nebraska State Legislature. Chambers would go on to serve as the singular, most dominant voice in Nebraska’s Black politics for the next four decades. His 1971 entry into the Unicameral coincided with a period of intense legal friction, specifically the Rice/Poindexter case. The 1970 bombing that killed an Omaha police officer led to the conviction of Black Panther leaders David Rice (Mondo we Langa) and Ed Poindexter. Throughout the 1970s, the community rallied behind the “Omaha Two,” asserting that the trial was a political frame-up orchestrated by the FBI’s COINTELPRO. This case became a permanent fixture of Black political discourse in the city, representing the adversarial relationship between North Omaha and the judicial system.

The 1980s brought a significant shift in municipal representation. For nearly a century, Omaha’s “at-large” election system had effectively shut Black candidates out of the City Council, as they could not overcome the majority white vote citywide. Activists pushed for a move to district-based elections, which was finally achieved in 1981. This change immediately bore fruit with the election of Fred Conley, who became the first African American on the City Council since the 1890s. Conley’s tenure (1981–1989) allowed for the first time a direct legislative focus on the infrastructure and economic needs of North Omaha. This period also saw the rising influence of Brenda Council, who served on the Omaha School Board before joining the City Council. Council became a symbol of a new, professionalized Black political class that was capable of building broad coalitions.

The final decade of the century, the 1990s, was an era of both significant breakthroughs and persistent barriers. In 1992, Carol Woods Harris became the first African American elected to the Douglas County Board of Commissioners. However, the most high-profile political event of the decade was Brenda Council’s 1997 mayoral campaign. Running against incumbent Hal Daub, Council built a historic coalition that nearly broke the executive glass ceiling. She lost by a mere 700 votes—a result that both devastated and inspired the community. The 1990s ended with the demolition of the Logan Fontenelle housing projects in 1996 and the end of court-ordered busing in 1999, events that signaled a “return to neighborhood schools” and a new, more complex era of de facto segregation. By the end of 1999, the foundation had been laid for the 21st-century breakthroughs, as leaders like John Ewing Jr. and a younger generation of activists prepared to take the mantle from the titans of the civil rights era.

Omaha Black Politics in the 21st Century

The period between 2000 and 2026 represents a transformative era in Omaha’s Black political history, characterized by a shift from the singular, long-term influence of legendary figures to a more diversified, multi-generational leadership that eventually broke the “glass ceiling” of the city’s executive branch.

At the dawn of the 21st century, Black politics in Omaha was still largely defined by the presence of Ernie Chambers. Having served since 1971, Chambers’ influence was so pervasive that the Nebraska Legislature enacted term limits in 2005 specifically aimed at ending his tenure. This triggered a period of legislative transition where leaders like Brenda Council and Tanya Cook stepped into the breach, bringing a more collaborative but equally determined focus on urban development and educational equity. When Chambers was legally allowed to return to his seat in 2013, he did so in a changed landscape where younger activists were beginning to demand more than just legislative defense; they wanted proactive community investment.

This desire for proactive change was catalyzed by the 2020 James Scurlock protests. The death of Scurlock during the George Floyd demonstrations served as a political lightning rod, mobilizing a new generation of organizers. Figures like Justin Wayne and Terrell McKinney emerged from this environment to take seats in the Unicameral. They represented a “New Guard” that was less tied to traditional party structures and more focused on specific policy outcomes, such as the North Omaha Recovery Plan, which sought to address the 60% child poverty rate that had plagued the community for decades.

Simultaneously, the quest for higher-level representation moved toward the county and federal stages. John Ewing Jr., a former police officer, became a steadying force in Douglas County politics as Treasurer beginning in 2006. His ability to win citywide and countywide support demonstrated a growing viability for Black candidates outside the historic North Omaha corridor. Meanwhile, Preston Love Jr. utilized his 2020 and 2024 Senate campaigns to nationalize Omaha’s local issues, focusing on voting rights and the “Black Votes Matter” initiative.

The era reached its historic zenith in the 2025 municipal election cycle. For decades, Black candidates had come close to the mayoralty—most notably Brenda Council’s 700-vote loss in 1997—but the executive office remained out of reach. In 2025, John Ewing Jr. synthesized his decades of public service and his reputation for fiscal responsibility into a historic mayoral campaign. By building a “bridge coalition” that united North Omaha with the city’s rapidly diversifying suburbs, Ewing was elected as the first African American Mayor of Omaha.

As of 2026, Black politics in Omaha is no longer a localized struggle for a seat at the table; it is a leading force in the city’s governance. The current landscape is focused on the “Omaha 2030” initiatives, aiming to dismantle the redlining legacies of the past through the executive power that the community fought 170 years to obtain.

Fast Facts About Black Political Action in Omaha

- FIFTEEN: There have been 15 African American members of the Nebraska Legislature from North Omaha.

- 1890: The first Black person to run for the Omaha City Council and the Nebraska Legislature was Edwin R. Overall, who lost in 1890.

- NINETEEN: There was a 19-year gap between the first Black legislator and the second one (1897-1926), but there have been no gaps since.

- EACH PARTY: From 1892 to 2023, African American legislators have included seven Republicans, seven Democrats, and one Independent.

- FORTY-SIX: Ernie Chambers is the longest-serving state senator in Nebraska history, having represented North Omaha for 46 years.

- 1893: The first African American man elected to the former Nebraska House of Representatives was Dr. Matthew Ricketts in 1893.

- 1937: The first African American man elected to the unicameral Nebraska Legislature was John Adams, Jr., in 1937.

- 1977: The first African American woman appointed to the Nebraska Legislature was JoAnn Maxey of Lincoln in 1977.

- 1895: Annie R. Woodbey was the first African American woman nominated for political office in Nebraska nominated for the University of Nebraska Board of Regents in 1895.

- 2009: The first African American women elected to the Nebraska Legislature were Tanya Cook and Brenda Council in 2009.

- EACH ONE: Almost every African American legislator in Nebraska was elected from North Omaha, except JoAnn Maxey of Lincoln.

- 1912: The Omaha chapter of the NAACP, founded in 1912, was the first chapter west of the Mississippi River.

- 1950: The first Black woman elected to public office in Omaha was Elizabeth Davis Pittman, who won a seat on the Omaha School Board in 1950.

- 1992: Carol Woods Harris was the first African American elected as a Douglas County Commissioner.

- 1971: Fred Conley was the first African American elected to the Omaha City Council in 1981.

- 2025: n 2025, John Ewing Jr. was elected the first African American mayor of Omaha.

- 1869: The first Black federal employee in Nebraska was Edwin R. Overall in 1869, who worked as a general delivery clerk for the post office.

- 11 PERCENT: Omaha’s Black population in 1856 was 13 residents, or 1.2% of the city’s population, and it grew to 57,883 residents, or 11% of the population, by 2020.

- 1927: The Omaha Urban League, founded in 1927, was the first chapter west of the Mississippi River.

- 1971: The first African American woman appointed as a judge in Nebraska was Elizabeth Davis Pittman in 1971.

Omaha’s African American Elected Officials

| Politician | Office(s) Held | Years Served | Life | Party | District |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matthew Ricketts | State Legislator | 1893–1897 | 1858–1917 | Republican | |

| John A. Singleton | State Legislator | 1926–1928 | 1895–1970 | Republican then Democrat | 9th |

| Ferdinand L. Barnett | State Legislator | 1927–1928 | 1854–1932 | Republican | 10th |

| Aaron M. McMillan | State Legislator | 1929–1930 | 1895–1980 | Republican | 9th |

| Johnny Owen | State Legislator | 1932–1935 | 1907–1978 | Democrat | 9th |

| John Adams, Jr. | State Legislator | 1935–1941 | 1906–1999 | Republican | 9th |

| John Adams, Sr. | State Legislator | 1949–1962 | 1876-1962 | Republican | 5th |

| Edward Danner | State Legislator | 1963–1970 | 1900–1970 | Democrat | 11th |

| George W. Althouse | State Legislator | 1970 | 1896–1981 | Republican | 11th |

| Ernie Chambers | State Legislator | 1971–2009, 2013–2020 | 1937– | Independent | 11th |

| Brenda J. Council | Omaha School Board; Omaha City Council; State Legislator | 1982-1988 (OPSB); 1994-1998 (OCC); 2009–2013 (NL) | 1955–present | Democrat | 11th |

| Tanya Cook | State Legislator | 2009–2016 | 1964–present | Democrat | 13th |

| Justin Wayne | State Legislator | 2017-present | 1979–present | Democrat | 13th |

| Terrell McKinney | State Legislator | 2020-present | 1990-present | Democrat | 11th |

| Fred Conley | Omaha City Council | 1981-1993 | |||

| Carol Woods Harris | Douglas County Board | 1992-2004 | |||

| Thomas Warren | Police Chief | 2003- | |||

| John Ewing Jr. | Douglas County Treasurer; Mayor | 2007-2015; 2025-present | Democrat |

You Might Like…

MY ARTICLES ABOUT BLACK HISTORY IN OMAHA

MAIN TOPICS: Black Heritage Sites | Black Churches | Black Hotels | Segregated Hospitals | Segregated Schools | Black Businesses | Black Politics | Black Newspapers | Black Firefighters | Black Policeman | Black Women | Black Legislators | Black Firsts | Social Clubs | Military Service Members | Sports

PIONEER BLACK OMAHA: Black People in Omaha Before 1850 | The First Black Neighborhood | Black Voting in Omaha Before 1870 | Racist Laws Before 1900 |

EVENTS: Stone Soul Picnic | Native Omahans Day | Congress of Black and White Americans | Harlem Renaissance in North Omaha

RELATED: Race and Racism | Civil Rights Movement | Police Brutality | Redlining

NEBRASKA BLACK HISTORY: Enslavement in Nebraska | Underground Railroad in Nebraska | Grand Island |

TIMELINES: Racism | Black Politics | Civil Rights | The Last 25 Years

RESOURCES: Book: #OmahaBlackHistory: African American People, Places and Events from the History of Omaha, Nebraska | Bibliography: Omaha Black History Bibliography | Video: “OmahaBlackHistory 1804 to 1930” | Podcast: “Celebrating Black History in Omaha”

MY ARTICLES ABOUT CIVIL RIGHTS IN OMAHA

General: History of Racism | Timeline of Racism

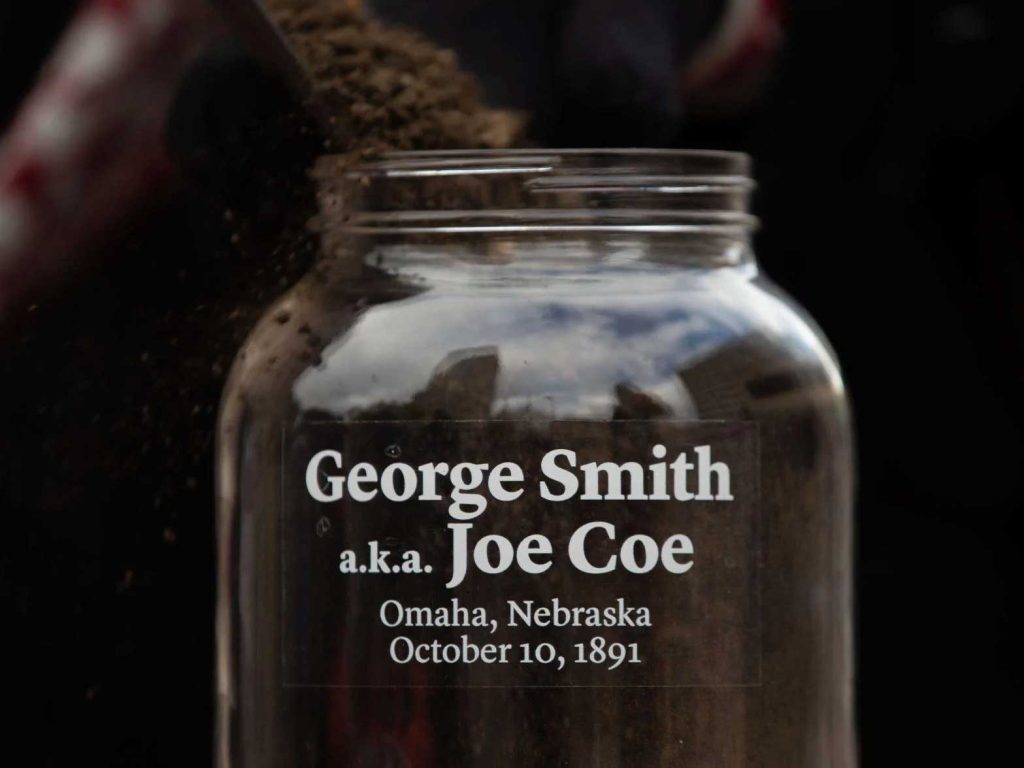

Events: Juneteenth | Malcolm X Day | Congress of White and Colored Americans | George Smith Lynching | Will Brown Lynching | North Omaha Riots | Vivian Strong Murder | Jack Johnson Riot | Omaha Bus Boycott (1952-1954)

Issues: African American Firsts in Omaha | Police Brutality | North Omaha African American Legislators | North Omaha Community Leaders | Segregated Schools | Segregated Hospitals | Segregated Hotels | Segregated Sports | Segregated Businesses | Segregated Churches | Redlining | African American Police | African American Firefighters | Lead Poisoning

People: Rev. Dr. John Albert Williams | Edwin Overall | Harrison J. Pinkett | Vic Walker | Joseph Carr | Rev. Russel Taylor | Dr. Craig Morris | Mildred Brown | Dr. John Singleton | Ernie Chambers | Malcolm X | Dr. Wesley Jones | S. E. Gilbert | Fred Conley |

Organizations: Omaha Colored Commercial Club | Omaha NAACP | Omaha Urban League | 4CL (Citizens Coordinating Committee for Civil Rights) | DePorres Club | Omaha Black Panthers | City Interracial Committee | Providence Hospital | American Legion | Elks Club | Prince Hall Masons | BANTU | Tomorrow’s World Club |

Related: Black History | African American Firsts | A Time for Burning | Omaha KKK | Committee of 5,000

Elsewhere Online

- North Omaha History Podcast Episode 2: Early African American Leaders in Omaha – Adam Fletcher Sasse takes us back to the 19th century to let us know about Omaha’s earliest African American leaders including Silas Robbins, Dr. Matthew Ricketts, the Singleton family, John Grant Pegg and into the 20th century with Clarence Wigington and Mildred Brown. (March 7, 2017; 15 mins) Listen online or download on iTunes

- North Omaha History Podcast Episode 3: Early North Omaha Community Leaders, Part 1 – In this episode, Adam Fletcher Sasse talks about early leaders in the Omaha community, including, believe it or not, Brigham Young! Also, learn about the founders of Florence, Saratoga, and Sulphur Springs, as well as the Kountze brothers. (March 7, 2017; 14 mins). Listen online or download on iTunes

Bonus Pics!

Leave a Reply to Race and Racism Timeline – North Omaha HistoryCancel reply