North Omaha has seen its share of community leaders. From its early roots as a suburb and country home for Omaha’s wealthy elite, to its successful middle class in-fill with European immigrants and Southern Blacks, to its moderation as a working class enclave for African Americans in Omaha, the community has lived through a lot. Today, leaders in North Omaha continue to grow the heart and soul of the community. This is a history of community leaders in North Omaha.

Early Leaders in North Omaha

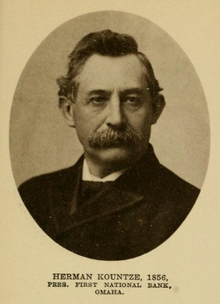

Shown (starting upper left): Herman Kountze, Cecilia Clenlans, George Miller, Edwin Overall, James Parker, Anna Woodbey, and George Lake.

Omaha was founded by a variety of people, many of whom concentrated on the little village downtown. However, to the north of that village leadership was sprouting at the same time.

The first leaders in North Omaha may have been the tribes that used the area for hunting for thousands of years, starting with the Woodland people, then extending to the 1700s and 1800s when the Omaha, Oto, Pawnee, and others swept through in hunts and travels through the middle of the North American continent. When they came through the area in 1804, Lewis and Clark found a large Otoe village of earthen lodges covering the plateau between N. 16th and N. 30th from approximately Cuming to Hamilton Streets. The first community leaders in the North Omaha area would have lived there.

In 1846, Brigham Young led his Mormon pioneers westward into present-day North Omaha. Almost a decade after they left camp, James Mitchell founded the town of Florence in their place. Banker James Parker was important in North Omaha, as was Erastus Beadle. Beadle, working on behalf of a New York-based investors group, rallied settlers into a town called Saratoga and village called Sulphur Springs between the North Freeway and Carter Lake, from Locust to Fort Streets. His leadership caused that little place to boom to 600 residents in a year; when the funders pulled their backing within a year, Beadle moved on.

In the next quarter century, people continued to come and go through North Omaha. Every decade surely saw its boosters and drivers, and many leaders probably came and went. Herman Kountze began his North Omaha suburb slowly, and his brother Augustus Kountze sold a big pocket of land to the US Army for a song to ensure their investment in the city. Dr. George L. Miller invested carefully in the area, and other moguls built their mansions in the community. However, the next big splash was very important to Omaha as a city, and North Omaha as a community.

Growing Into the City

A vital thing happened in the 1870s though. In that decade, African Americans began moving to Omaha as part of a national trend of Blacks moving from the South to cities in the north. By the early 1880s Omaha had approximately 500 black people who lived there; by 1900 there were 1000. Every ethnic group in North Omaha had its leaders, and the Black community wasn’t different than others.

Edwin Overall was the first African American to run for the Omaha City Council. The second African American to run for the Nebraska State Legislature was Silas Robbins, who ran in 1887 and lost. Two years later he became the first African American in Omaha allowed to join the Nebraska Bar Association. Dr. Matthew Ricketts was 26 years old when he graduated from the Omaha Medical College, becoming the first African American graduate of what eventually became the University of Nebraska College of Medicine. When he was 38 years old, Dr. Ricketts became the first African American elected to the Nebraska State Legislature. Ricketts acted as a monitor and temper for North Omaha, sharing information with the community and acting as a conduit for political power in the community.

Millard Singleton was a close ally of Dr. Ricketts, and in 1889 was elected vice president of an Omaha Colored Republican Club. He was president in 1896 and 1912. In 1890, he helped form a Nebraska branch of the Afro-American League in Omaha. In 1889 was elected vice president of an Omaha Colored Republican Club, and was president in 1896 and 1912. He helped form the Nebraska branch of the Afro-American League in North Omaha in 1912, and was the Nebraska representative to the Colored Men’s convention. In 1892, he was an Omaha delegate at the Republican National Convention in Minneapolis, and in 1895, he was named a Justice of the Peace. He ran to replace M. O. Ricketts as the Republican nominee for state legislature in 1896, but lost. During this era, Rev. Anna Woodbey was a leader throughout the community, including in the temperance movement and the struggle for women’s suffrage.

Millard’s son, Dr. John A. Singleton, was also very active and influential in North Omaha politics and community leadership. Serving as the Deputy Register of Deeds of Douglas County in the early 1920s, he was a delegate to the Republican County Central Committee in 1926. In 1926, he ran for a seat in the Nebraska House of Representatives, eventually winning. Just two years later though, he was defeated in the primary election by fellow Black Republican Dr. Aaron M. McMillan. He ran again in 1930, losing in the primary to E F Fogarty and to Johnny Owen in 1932. Singleton generally supported Omaha’s Republican mayors, saying that Mayor Dahlman and Mayor Richard Lee Metcalfe were friends to Black people. In 1926, he supported Omaha boss Tom Dennison’s Square Seven ticket. On the evening of April 16, 1930, a cross was burnt by KKK members on Singleton’s lawn. John was away, but his wife and niece were there. His father, Millard, arrived shortly and tore down the cross in front of a large crowd.

John Grant Pegg came to Omaha in 1898. Pegg was voted as a Republican committeeman for the Near North Side neighborhood, and was considered the “councilman for the Black community.” In 1910, Pegg became the first African American appointed Inspector of Weights & Measures for the City of Omaha. According to BlackPast.org, “His work in the black community led him to be known as a “race man” dedicated to improving the African American section of Omaha’s population. Pegg, for example, was a Shriner and a member of a local Masonic Lodge.”

Walter J. Singleton was a North Omaha journalist and an editor of the Omaha Progress, an African American newspaper for the community, and was a close ally of State Senator Ricketts.

Early African American institutions that brought leadership to North Omaha included St. John’s African Methodist Episcopal Church, Pilgrim Baptist Church, and other historic Black churches.

All of these leaders created an essential blanket of energy and vitality in the neighborhood during this time. Through their political, social and cultural actions, they created presence, power and sustenance for themselves, their peers and the entirety of North Omaha.

Uniting African Americans

While Omaha was growing up, North Omaha was maturing while its community members enriched its community fabric.

Within the North Omaha’s Jewish community, several religious leaders kept members educated, fed, employed and forward-thinking. Omaha’s Jewish laity, including many prestigious businessmen and later politicians, eventually moved the community out of North Omaha towards the more affluent west Omaha communities where most Omaha Jewish people live today.

After the lynching of Will Brown, Omaha’s African American community became redlined within the confines of the Near North Side during this era. Previously spread through downtown Omaha and South Omaha, the violence of racism and government-led segregation drove almost all of Omaha’s Black community into North Omaha between 1919 and 1921. Omaha’s Black community didn’t accept this lying down. Rather, it rose to the challenge and began organizing and activating for change.

By the 1920s, 40 black congregations had formed in North Omaha, acting as an extended family for the newcomers and providing North Omaha with leadership. During this era, Rev. Russel Taylor (1871-1933) led St. Paul Presbyterian Church as a minister, teacher, musician, activist, and former homesteader. He was a widely recognized leader in Omaha’s Black community in the 1920s.

In another instance, instead of following the deep history of traditional African American congregations, Lizzie Robinson and her husband Eddie founded the first Church of God in Christ congregation in Omaha in 1916. Their work took decades to join the ranks of the mainline Black denominations, but today their service has given the city more than 20 congregations.

Similar to the Robinsons, Mildred D. Brown arrived in Omaha with her husband. After arriving in 1937, the couple founded the Omaha Star the following year. Her leadership continues to be recognized today, more than 15 years after her death. Brown is credited with helping lead the city’s civil rights movement throughout her entire life.

Pro-Black activism began in North Omaha during this time, with leadership for the community emanating from within the community. George Wells Parker was 34 years old when he started recruiting African Americans from the South to move to Omaha, in 1916. During that same time he founded the Hamitic League of the World, an organization promoting Afrocentrism, which eventually evolved into the African Blood Brotherhood. Similarly, Harry Haywood, born in South Omaha, was 16 when he moved to Chicago and was targeted by the Chicago Race Riots. However, his impact on the community wrang through the coming years as the radical organizing of the Communist Party focused on laborers in North and South Omaha. This leadership was matched by the work of Earl Little, who organized for Marcus Garvey’s United Negro Improvement Association in North Omaha and was forced to leave by the city’s KKK after his son Malcolm was born. While Helen Mahammitt was a popular chef and educator in the community, she was a popular educator who helped grow several generations of North Omaha families.

The community’s cultural leadership surged during this era, too. Entrepreneurs built clubs to entertain people, including Jim Bell’s Club Harlem, James Jewell’s Dreamland Ballroom and Mildred Brown’s Carnation Ballroom. Through careful planning and deliberate negotiations, careers were launched and fame was promoted. Performers including Nat King Cole, Dinah Washington, Earl Hines, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Louis Armstrong and Lionel Hampton came through Omaha. Other musicians, including Preston Love, Anna Mae Winburn, Lloyd Hunter, Wynonie Harris and Dan Desdunes launched their national careers from Omaha.

Building Institutions in the Community

Some individuals in North Omaha were institutions unto themselves. Many of the political leaders above were prominent and highly influential. However, others who weren’t in politics often found themselves in community leadership positions, too. Johnny Owens, who served as a member of the Nebraska House of Representatives representing Omaha, was one of those figures. After a powerhouse athletic experience in high school, he was denied admission to UNL because of their racist anti-Black registration policies. Later serving in the legislature for one term, Owen fought against Prohibition and was an advocate for civil rights. However, soon defeated by another African American, Owen gained a lot of power in North Omaha and became known as the “Negro mayor of Omaha.”

Harrison J. Pinkett was a Howard University-educated lawyer who practiced law in Omaha for more than 50 years. A lawyer for the Omaha chapter of the NAACP, he was also started a church in North O, served as a US Army officer in WWI, published a Black newspaper, advocated stringently for Civil Rights, and much more. He was an opponent of Tom Dennison’s dynasty, and supported Omaha’s Anti-Saloon League.

Working with other Black leaders including Rev. John Albert Williams, John Singleton, and T P Mahammitt, Pinkett helped create Omaha’s Colored Commercial Club to support black business in Omaha. Williams spearheaded the creation of the St. Phillip the Deacon Episcopal Church, a Black church located by North 21st and Paul Streets. He was responsible for starting Omaha’s NAACP chapter in 1914, and in the 1920s, he spoke out strongly against the Omaha World-Herald when they published the remarks of KKK imperial wizard Hiram Wesley Evans. Williams also published his own newspaper called The Monitor both before and after World War I, and was involved in several other activities throughout the community as well.

Lucinda Williams, nee Lucy Gamble, was the first African American teacher in Omaha Public Schools. Like her husband Rev. Williams, Mrs. Williams was an active leader throughout North Omaha all of her life. She was very active in her husband’s church, leading the choir and playing organ, as well as a leader in the segregated North Side YWCA, the Colored Old Folks Home, joining the board of the Omaha Community Chest, and other activities.

In 1933 and 1936, Harrison Pinkett ran for the post of city commissioner and lost both times. He continued to write letters to the editor in support of civil rights as well as work as a defense attorney and as counsel for the NAACP in Omaha until his death in 1960.

Other North Omaha leaders literally built institutions in the community.

When predominant Omaha architect Thomas Rogers Kimball became too busy he started taking students to apprentice with him. Nineteen-year-old Clarence W. Wigington left art school in 1902, joining Kimball as his assistant. Seven years later his design for the Broomfield Rowhouse in Omaha won an award from Good Housekeeping magazine. Soon after Wigington left Omaha for St. Paul, Minnesota, where he became a master architect, with dozens of structures throughout the city. His early Rowhouse was designed for Jack Broomfield, who assumed political leadership in the North Omaha community after Dr. Ricketts moved to St. Joseph, Missouri.

Bertha Calloway’s familial legacy revolved around her son. After starting the Negro Historical Society with neighbors in North Omaha in 1962, Calloway opened the Great Plains Black History Museum in 1976 in the historic Webster Telephone Exchange Building. She handed over the reigns to her son Jim in the late 1990s, who lost essential funding from the City of Omaha, forcing the museum to close in 2001. Apparently there has been a recommitment of funding, and several renovations have been made and the museum is open again.

For several years Whitney Young led Omaha’s Urban League, organizing citizens throughout North Omaha in advocating for civil rights. Working out of the Webster Telephone Exchange Building, Young coordinated youth programs, employment programs and efforts to open a variety of jobs for African Americans that had never been opened before. His leadership led him to the national stage, and he later made significant gains for the civil rights movement across the country.

Other institutions were formed from the 1940s through the 1960s. In succession, the DePorres Club, 4CL, the Omaha Black Panthers and BANTU all took on the Civil Rights movement during that period. Their leadership in guiding the community was felt through changing discrimination practices and ongoing transformation of Omaha’s cultural fabric.

Leaders from this period of the history of North Omaha include Preston Love, Sr., Charles Washington, Mildred Brown, Beverly Wead Blackburn, Lizzy Robinson, and Tom Harvey. David Rice, later known as Mondo we Langa was very active throughout the community, writing for the Omaha Star and later founding his own newspaper, leading community activism projects and later leading the Omaha Black Panthers.

In a 1984 feature from the Omaha Star, several African American leaders are cited including Bertha Calloway, Ernie Chambers, A. B. “Buddy” Hogan, Eugene Skinner, Welcome T. Bryant, Dr. Claude Organ, Katherine L. Fletcher, Fred Conley, Gail Kinsley Thompson and Dr. Rodney S. Wead.

Others community leaders in North Omaha from the 1970s and 1980s included Bob Boozer, Cathy Hughes, John Beasley, Bob Gibson, Ron Boone, Calvin Keys, Brenda Council, Gayle and Roger Sayers, Johnny Rodgers, Warren Taylor, Tom Warren, Dan Goodwin, Gene McDaniel and Preston Love, Jr., among others. Others came and went during this era too, including Jack West and Matthew Stelly.

Leading North Omaha through Politics

The first session of the Nebraska unicameral legislature happened in 1936, and the only African American to serve in it was North Omahan John Adams, Jr., an African American lawyer and Republican politician. Before, he served in the last session of the Nebraska House of Representatives. He introduced Nebraska’s first public housing law in the early 1930s, and supported other welfare legislation. Active in the national scene, he was also an honorary sergeant at arms at the 1936 Republican National Convention and a Judge Advocate at Camp Knight in Oakland, California during World War II. During his terms in the legislature, the Omaha World-Herald called him one of the Legislature’s 16 “most able members.” As a lawyer, Adams fought an early trial against Jim Crow rules in Omaha and other discriminatory practices.

Adams Jr.’s father, John Adams, Sr., followed him into the Nebraska Legislature. A lawyer and minister in the A.M.E. church, he was the only black member of the Nebraska unicameral for much of his tenure from 1949–1962. After leading Nebraska’s AME churches for a number of years, he was presiding elder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) when he passed away. As a legislator, he was an outspoken champion of civil rights and fought for fair employment practices and pensions for retired teachers.

Dr. Andrew McMillan led many efforts to improve North Omaha. In addition to serving the community as a doctor for decades, he also ran against dentist John Singleton for Nebraska Legislature and won, serving a single term. McMillan opened the People’s Hospital to provide free care for North Omaha after returning from missionary work in Angola, keeping it open for five years.

Brenda Council is a lawyer in Omaha today. She was first elected to public office in 1982, when she served on the Omaha Board of Education for eleven years as the first African American on the board. In 1993 she became the first African American woman to serve on the Omaha City Council. She ran for mayor of Omaha twice, loosing only by slim margins. Today she’s running for the Nebraska State Legislature seat vacated by Ernie Chambers.

In modern times many people are familiar with the work of State Senator Ernie Chambers. Chambers served North Omaha as a legislator for more than 35 years, after finishing a law degree at Creighton University and working as a barber at the Spencer Street Barber Shop. Ernie believes the Nebraska State Legislature created its term limit law specifically to get him out of office, and he may be right. However, he hasn’t been the only leader in Omaha’s African American community.

When Mildred Brown passed away in 1989, she ensured the continued existence of North Omaha’s leading newspaper and the only newspaper for African Americans in Nebraska, The Omaha Star. She did this by bequeathing it to her niece, Dr. Marguerita Washington. Already well-established as an educator in the Omaha Public Schools, Dr. Washington took over the mantle of the paper and secured it. Her leadership took the entire North Omaha community to new heights, too.

Future Leaders

It would be impossible to recount all of the community leaders in the history of North Omaha. A variety of religious, social, educational and labor leaders have left their impact on the community. This sampling shows that communities are cyclical places, with leaders coming and going throughout time. As for the emergence of future leaders, North Omaha needs them as ever before. Hopefully those days are ahead.

You Might Like…

- A History of Black-Owned Businesses in North Omaha

- A History of North Omaha’s African American Legislators

- A History of the Omaha Colored Commercial Club

- A History of Crime Bosses In North Omaha

Elsewhere Online

- Leo Adam Biga (2014) “Next generation of North Omaha leaders eager for change” for The Reader

- North Omaha History Podcast: Listen to my podcast called “Early African American Leaders in North Omaha” FREE right now!

Leave a comment