From 1892 to 1978, a large building dominated the corner of 16th and Corby. It was a busy corner for more than a half century, with a massive movie theater and large stores on each corner. However, this building seemingly came and went with little fanfare, until now. This is a history of the Kyner Block at North 16th and Corby Streets in North Omaha.

The Building

The history of the lot at the southeast corner of North 16th Street and Corby Street begins with its position along the developing corridor once known as Sherman Avenue. In the 1880s, property records identified this specific tract of land as the holdings of the heirs of S. Kyner. Their grandson, J. H. Kyner (1846-1939), was a railroad builder and Civil War veteran who had moved to Omaha in 1878. Within a few years in his successful career, he managed a vast real estate portfolio in the city worth $250,000. As a contractor, Kyner was one of the main developers in North Omaha, grading streets for his neighborhood’s grid, including Sherman Avenue.

During the 1880s, the Kyner family grew in its powers and their land was in an importantly booming area, situated near the large estates of early Omaha figures like Herman Kountze, yet poised for the dense commercial expansion that followed the city’s northward growth. Located just south of the massively important intersection of 16th and Locust, in the 1880s, Sherman Avenue was becoming this was a busy street that was just beginning to build up. By the early 1890s, it was located on the streetcar line to the East Omaha Factory District and led to the bustling Saratoga neighborhood, the industrial railroad roundhouses in Sulphur Springs, and other important industries nearby. Surrounded by the Kountze Place and Lake School neighborhoods, North 16th Street was also on the commuter’s journey to the village of Carter Lake, the town of East Omaha, and the growing Sherman neighborhood.

In 1892, a building permit was issued to Naomi Kyner (1852-1895) for $35,000 that marked the final chapter of the rural past in this section of North Omaha. It was a huge investment that changed the whole neighborhood by building a massive structure that effectively became a permanent commercial anchor. The new half-block long structure called the Kyner Block measured 150 feet along North 16th, and was 85 feet deep.

With businesses on the bottom and apartments on the top, this building had what is called a “St. Louis Flat” desgin. The building had four distinct street addresses, including 2621, 2623, 2625, and 2627 North 16th Street. The building had a flat roofline with intricate Neo-Classical terra cotta relief panels along the top and big wooden bay windows hanging over the sidewalk, letting light inside the apartments.

The ground floor had seven individual storefronts that housed a variety of retail operations for the growing neighborhood around the block. Located across the street from the Corby Theater, there were a number of other businesses around the Kyner Block, and it was just a block south of the very busy intersection of 16th and Locust.

For Sale

The financial history of the Kyner Block mirrored North Omaha’s economic rise and fall. In 1892, Naomi Kyner invested a peak sum of $35,000 to construct the brick behemoth. Following an economic depression in the 1890s, National Life Insurance managed the building until selling it to S. R. Cox in 1905 for $25,000. Value came back by 1907, though, when W. J. Hynes bought the block for $33,000.

The 1920s saw aggressive speculation in the property, and the Kyner Block reached the top valuation of its existence in 1923 when it sold for $100,000. However, just a year later it dropped to $56,000 in 1924. Investors flipped the building again in 1925 for $75,000.

Starting in 1934, the region of North Omaha next to the building was redlined by the federal government and systemic divestment eventually eroded these gains. By 1939, the price fell back to $25,000, and from then onward the decline culminated. In 1968, the entire block was marketed for just $30,000—less than its 1892 cost when adjusted for decades of inflation.

The Kyner Family in Omaha

The Kyner family’s presence in Omaha was defined by the ambitious trajectory of Jim Kyner (1846-1939), a Union veteran of the Civil War who came to the city in 1878 after losing a leg at the Battle of Shiloh. Jim quickly climbed the city’s social and political ranks, winning a seat in the Nebraska Legislature in 1881 and again in 1887. His political influence was mirrored by his professional success as a railroad magnate and contractor who was responsible for grading many of North Omaha’s early streets and the local meatpacking center.

By the late 1880s, property records identified the family’s significant holdings as the land of the “Heirs of S. Kyner” at 16th and Corby. In 1892, Jim’s wife Naomi got a permit to build the Kyner Block, a massive brick development of stores and flats that served as a monument to their real estate empire. The new building would cost $35,000; their empire was worth $250,000. After his wife’s sudden death in 1895, the family suffered financial ruin. Jim later moved to Maryland and recovered.

Despite the street originally named in their honor having been changed, the Kyner name remained etched in Omaha’s architectural and political history through the landmark building that anchored North 16th Street for 85 years.

The Businesses

The business history of the Kyner Block shows that it was a neighborhood commercial anchor for the surrounding area. Right after it opened for business in 1893, the building quickly became an essential service location. By 1899, the corner storefront at 16th and Corby was a pharmacy and the Omaha Post Office sub-station number 5.

A decade later in that same spot, Swedish grocers Danielson & Landen opened a large store, and the rest of the storefronts on the block had busy shops in them, too. After the Kyner family lost control of the building, it became an investment property owned by the National Life Insurance Company. They managed the six stores and six flats as a corporate asset until 1905. By 1913, the Omaha Furniture and Carpet Company used the storefronts as secondary showrooms and warehouses. During Prohibition in the 1920s, the corner storefront became a “soft drink parlor” where an owner named L. G. Larson was licensed to sell carbonated waters and near-beer to circumvent dry laws.

After Prohibition was repealed in 1933, the new anchor of the block became the Storz Beer Tavern, a social landmark easily identified by its massive circular signage. The Storz Brewery, located a mile and a half south, had a number of “tied taverns” around Omaha that exclusively sold their beer. This particular tavern was owned by the brewery though, and kept the suds flowing to the working class homes around the Kyner Block. For more than 15 years starting in the 1930s, Stoner Van and Storage kept an office in the building. Their space was taken over in 1951 when Max I. Walker Cleaners moved in. They stayed until 1963.

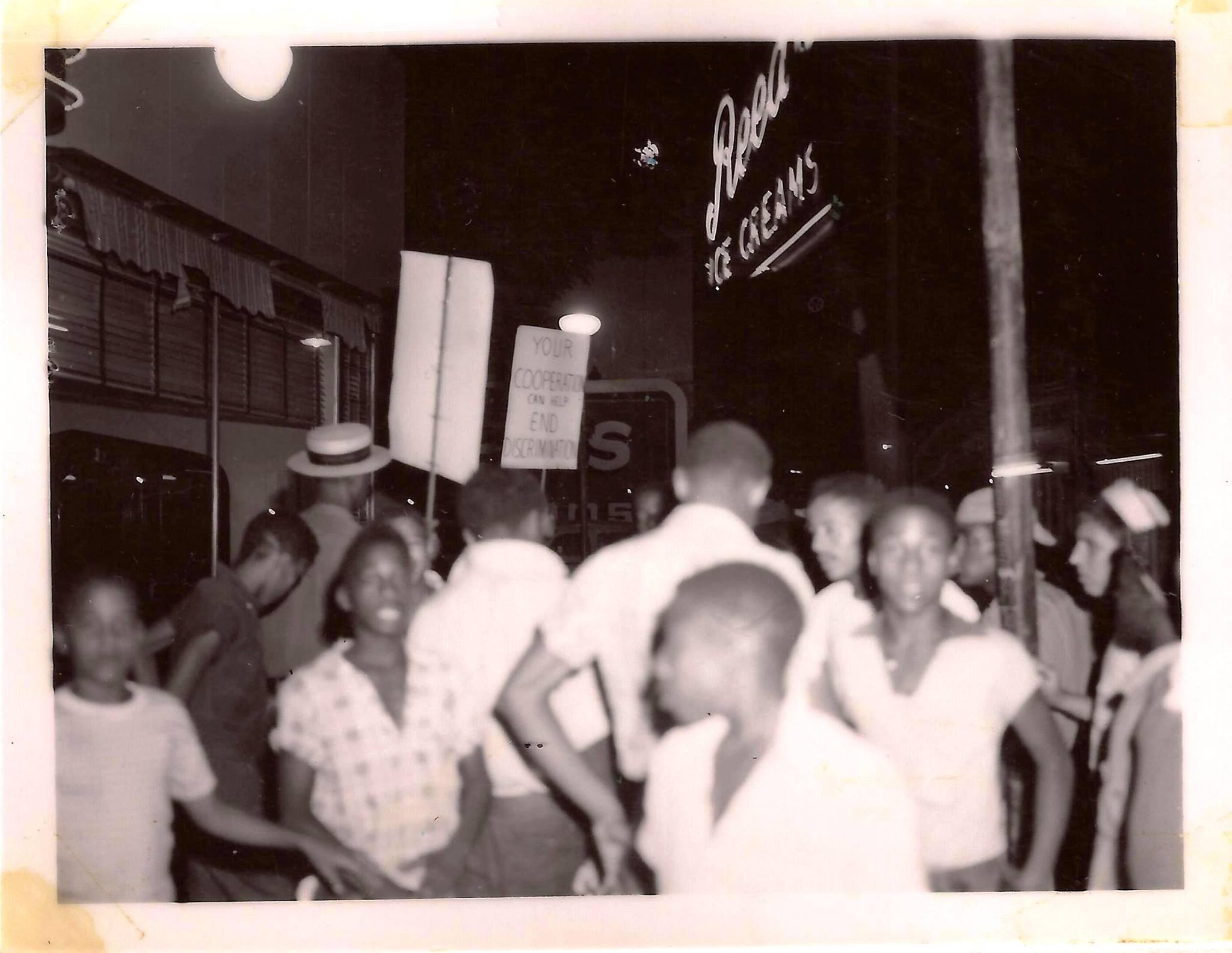

Throughout the decades, storefronts in the block branched out into niche markets including the mid-century Italian ice cream parlor operated by Mrs. S. Maddalena (1902-1997), which specialized in gelati and spumoni. The mid-century years saw the building firmly established as a segregated white ethnic enclave, with residential units occupied by skilled professionals such as Victor J. Hoile, a regional representative for an industrial firm. This demographic remained unchanged through the 1950s, with every census record confirming that Black residents were excluded from the building’s apartments until the socio-economic collapse of the North 16th Street corridor in the late 1960s.

One of the last businesses in the Kyner Block was Paul’s Grocery, which operated from the late 1940s until the mid-1970s on the corner. Run by Paul Cattano (1895-1977), an Italian immigrant, the business thrived for a few decades until the neighborhood fell into deep economic dejection. The transition from a stable white business hub to a property in need of repair coincided with the passage of the Fair Housing Act, marking the final chapter of the Kyner Block’s life. By the time it was destroyed by arson in 1978, the building had transformed from a prestigious thirty-five thousand dollar “behemoth” into a distressed asset, yet it left behind a rich record of labor disputes, federal service, and shifting cultural boundaries.

The Apartments

On the second floor were six large apartments that housed dozens of people over the decades. For 50 years, these apartments were segregated and didn’t allow African American renters. By the time the Fair Housing Act passed Congress in 1968, white flight in this entire region of North Omaha was well underway and nearly complete.

Based on the archival records and census data I have uncovered, the Kyner Block was a racially segregated residential and commercial space for more than 75 years. From its construction in 1892 through the mid-twentieth century, every census record for the apartments and storefront addresses at 2621, 2623, 2625, and 2627 North 16th Street identifies the occupants exclusively as white. During the early 1900s, these residents were primarily of Scandinavian and Germanic descent, eventually transitioning into an Italian-American enclave defined by families like the Cattanos and Maddalenas. It was only after the passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968 and the subsequent economic divestment of the area that the first African American and Latinx tenants were recorded in the 1970 census. This demographic shift occurred only as the building reached the end of its life, proving that the Kyner Block remained a segregated landmark until the legal end of Jim Crow in North Omaha.

De facto segregation was maintained by the rigid social and legal boundaries in Omaha, and North 16th Street was as a firm color line that kept Black people from renting or owning property east of 16th Street for a very long time.

The End

The Kyner Block was a casualty of severe divestment and instability that rocked all of North Omaha for a decade starting in the 1960s. Driven by white flight away from the community, by the 1960s, the City of Omaha began removing neighboring wood-frame buildings to the south and left the Kyner Block standing isolated on its corner. By 1968, there was an ad in the Omaha World-Herald advertising the building for sale, being “in need of repair. Ideal for a handyman.” Its cost then was $30,000, which was worth significantly less than when it was originally constructed. The decaying building was a product of the environment around it.

Then, on October 29, 1978, a massive fire—officially ruled as arson—destroyed the southern portion of the Kyner Block. The fire was so intense that it required two alarms with fire stations throughout the community responding. Blocking N. 16th St. for hours, it effectively gutting the southern units. Following the blaze, the remains of the entire block were cleared.

Crimes on the Block

The criminal history of the Kyner Block serves as a grim timeline of North Omaha’s deliberate, systemic destabilization. By the late 1960s, the building’s commercial stability was replaced by targeted violence. Paul Catano, the elderly immigrant owner of Paul’s Grocery, became a symbol of this era’s danger when he was burglarized in 1967 and survived being shot in the neck twice during separate 1971 and 1972 robberies.

As traditional businesses fled, illegal social hubs filled the vacuum on the block. In 1973, a police raid at 2623 North 16th Street targeted an after-hours gambling den known as the North Side Veterans Club, after breaking down the door officers seized pistols, rifles, and cash. Other storefronts, like a shoe repair shop at 2625 and Ye Olde Clippe Jointe at 2627, saw a revolving door of tenants as the block reached its breaking point. The building’s narrative ended in 1978 with the ultimate crime of arson, which leveled the structure and left behind the vacant, devalued lot that remains today. Nobody was found to blame for the arson.

Today

Today, the lot on the southeast corner of 16th and Corby is owned by the Omaha Land Bank and is currently valued at $5,600.

For almost 50 years since, the lot has sat empty with grass covering it. Located across the street from the old Corby Theater, which itself is crumbling now, the future of this corner doesn’t look positive. The once slam-packed North 16th Street is largely empty, too, and there are no signs of any kind left from the powerhouse Kyner Block and the economic engine it once served as. Maybe that will change in the future.

You Might Like…

MY ARTICLES ON THE HISTORY OF ARCHITECTURE IN NORTH OMAHA

GENERAL: Architectural Gems | The Oldest House | The Oldest Places

PLACES: Mansions and Estates | Apartments | Churches | Public Housing | Houses | Commercial Buildings | Hotels | Victorian Houses

PEOPLE: ‘Cap’ Clarence Wigington | Everett S. Dodds | Jacob Maag | George F. Shepard | John F. Bloom

HISTORIC HOUSES: Mergen House | Hoyer House | North Omaha’s Sod House | James C. Mitchell House | Charles Storz House | George F. Shepard House | 2902 N. 25th St. | 6327 Florence Blvd. | 1618 Emmet St. | John E. Reagan House

PUBLIC HOUSING: Logan Fontenelle | Spencer Street | Hilltop | Pleasantview | Myott Park aka Wintergreen

NORMAL HOUSES: 3155 Meredith Ave. | 5815 Florence Blvd. | 2936 N. 24th St. | 6711 N. 31st Ave. | 3210 N. 21st St. | 4517 Browne St. | 5833 Florence Blvd. | 1922 Wirt St. | 3467 N. 42nd St. | 5504 Kansas Ave. | Lost Blue Windows House | House of Tomorrow | 2003 Pinkney Street

HISTORIC APARTMENTS: Historic Apartments | Ernie Chambers Court, aka Strehlow Terrace | The Sherman Apartments | Logan Fontenelle Housing Projects | Spencer Street Projects | Hilltop Projects | Pleasantview Projects | Memmen Apartments | The Sherman | The Climmie | University Apartments | Campion House | Ivy / Fairfax Apartments

MANSIONS & ESTATES: Hillcrest Mansion | Burkenroad House aka Broadview Hotel aka Trimble Castle | McCreary Mansion | Parker Estate | J. J. Brown Mansion | Poppleton Estate | Rome Miller Mansion | Redick Mansion | Thomas Mansion | John E. Reagan House | Brandeis Country Home | Bailey Residence | Lantry – Thompson Mansion | McLain Mansion | Stroud Mansion | Anna Wilson’s Mansion | Zabriskie Mansion | The Governor’s Estate | Count Creighton House | John P. Bay House | Mercer Mansion | Hunt Mansion | Latenser Round House and the Bellweather Mansion

COMMERCIAL BUILDINGS: 4426 Florence Blvd. | 2410 Lake St. | 26th and Lake Streetcar Shop | 1324 N. 24th St. | 2936 N. 24th St. | 5901 N. 30th St. | 4402 Florence Blvd. | 4225 Florence Blvd. | 3702 N. 16th St. | House of Hope | Drive-In Restaurants

RELATED: Redlining | Neighborhoods | Streets | Streetcars | Churches | Schools

Leave a Reply