Enslaved people fought and struggled and battled against enslavement from the first ship coming to the English colonies in 1619. Contrary to what many historians have said, Nebraska didn’t escape slavery. People were enslaved here, a spur of the Underground Railroad (UGRR) ran though the southeast corner of the state, and many formerly enslaved people lived in Nebraska after the Civil War. As a lie told by pro-enslavers before the Civil War, people were told there was no slavery in the state, and afterwards people were taught the same in schools, books and the media.

However, as this article shows, it’s not that there weren’t slaves in Nebraska, it’s that white people past and present—including politicians, historians, government workers and teachers—have neglected and denied seeing them for the entire history of Nebraska.

Before you read further though, read this quote from William Wells Brown in 1847:

Slavery has never been represented; Slavery never can be represented… I may try to represent to you Slavery as it is; another may follow me and try to represent the condition of the Slave; we may all represent it as we think it is and yet we shall all fail to represent the real condition of the Slave.

—William Wells Brown, From A Lecture Delivered before the Female Anti-Slavery Society of Salem, November 14, 1847

This article will fail to successful portray slavery, enslavement, and freedom seekers in Nebraska. However, it is my attempt to share some of the facts about what happened. Please leave your questions, comments, concerns, considerations and criticisms in the comments section.

I. Before It Was “Nebraska”

After the U.S. made the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, it was legal to own enslaved people in Nebraska until 1861, with exceptions for those owned by federal employees and military officers. Of course, there were enslaved people in the territory with the first recorded in 1804.

York was an enslaved man who came to the future state with the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1804. The only Black man with the expedition, he was forced into service by his owner, William Clark, who inherited him five years earlier in 1799. York was tall and built large, with short hair and dark skin. Expecting to receive his freedom after the expedition finished, Clark would not grant him that, whipped him and eventually sold him. York’s fate is uncertain.

After that, there were enslaved people at Fort Lisa near present-day North Omaha during its existence from 1812 to 1820. This was a privately-owned fort run by a Spanish fur trader, and surrounded by as many as a dozen homes of it’s workers. Enslaved people were reported at the fort more than once.

Some antibellum Army officers in the Nebraska Territory were enslavers. They were stationed at the Missouri Encampment near North Omaha from 1819 to 1820, and the subsequent Fort Atkinson from 1820 to 1827 near present-day Ft. Calhoun. Renowned Black mountain man James Beckwourth (1800-1866) was a formerly enslaved man who traveled through Fort Atkinson as a freeman.

The Missouri Compromise of 1820 ensured slavery was legal in the Louisiana Territory, including the area that became the Nebraska Territory.

Nearby, Cabenné’s Trading Post had enslaved people from 1820 to 1832. This post was owned by another private business, and had a French postkeeper named Jean Cabenné. There were numerous enslaved people noted in journals from travelers, and some in the official bookkeeping of the business.

There were also enslaved people at the first Fort Kearny near Nebraska City from 1844 to 1848, and at the second Fort Kearny near present-day Kearney from 1848-1861. A formerly enslaved man came to the Omaha area in 1846 on a buffalo hunt with his enslaver.

The Church of Latter Day Saints held enslaved people at Winter Quarters from 1846 to 1848, and they traveled through while the location was active through 1861. Jacob Bankhead was the first recorded death of an enslaved person in Nebraska. He was traveling through the area with the Church of Latter Day Saints and is buried in an unmarked grave in the Mormon Cemetery in Florence.

More than 30 years after the Missouri Compromise, Congress renegotiated it with Republicans giving into to Democrats on the idea that slavery wouldn’t happen in the state because of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. This acquiescence led to another development.

At the beginning of 1854, a Northern Democrat senator who believed in enslavement named Stephen A. Douglas proposed a transcontinental railroad to promote western settlement. He knew it would be a huge moneymaker and he wanted in on the action! To get the votes form racist Southern Democrats also committed to enslavement, Douglas proposed the Kansas-Nebraska Act that divided the once-huge Nebraska territory into the Kansas Territory and Nebraska Territory. Settlers in these new territories would be able to vote whether they would allow slavery or not. They thought Nebraska would not allow slaves.

Enslaved people in Nebraska before it was organized into a territory included…

- (1804) York, (1770–75 – after 1815), man owned by William Clark, on the western banks of the Missouri River

- (1812-1820) Enslaved people, names and number unknown, at Fort Lisa near North Omaha

- (1819-1820) Enslaved people, names and number unknown, at the Cantonment Missouri near North Omaha

- (1820-1827) Enslaved people, names and number unknown, at Fort Atkinson near Ft. Calhoun

- (1820-1832) Enslaved people, names and number unknown, at Cabenné’s Post near North Omaha

- (1844-1848) Enslaved people, names and number unknown, at first Fort Kearny near Nebraska City

- (1846-1847) Hark Lay Wales (1825–1881), man owned by Mormons at Winter Quarters in North Omaha

- (1846-1847) Green Flake (1828-1903), man owned by Mormons at Winter Quarters in North Omaha

- (1846-1847) Henry Brown (18??–18??), man owned by Mormons at Winter Quarters in North Omaha

- (1848) Jacob Bankhead (18??–1848), man buried by Mormons at Winter Quarters in North Omaha

- (1848-1861) Enslaved people, names and number unknown, at second Fort Kearny near Kearney

Note that Jane Manning James (1813–1908) was a free Black woman who “was adopted as a servant into the family of Joseph Smith” but was not enslaved.

II. Slavery In the Nebraska Territory

Feelings against the self-determination of the Kansas-Nebraska Act were strong and a campaign called the Anti-Nebraska Movement spread across the country. This movement actually led to the formation of the Republican Party, created to be staunchly anti-slavery and to stop the Nebraska Territory from allowing slavery. It failed though, and the new Nebraskans were able to choose whether slavery would be allowed. While a few southern Nebraskans were recorded enslaving Black people, many northern Nebraskan politicians repeatedly said in the newspapers and the legislature that slavery did not exist in the territory and did not need to be addressed in law. Whether this was willful ignorance or genuine naivety is unclear.

Bringing his family and at least five enslaved people to the territory in early 1854, businessman Stephen Nuckolls founded Nebraska City on July 10, 1854. In 1855, a census recorded 13 enslaved people statewide, mostly in Nebraska City. According to the US census in 1860, there were 10 enslaved people in the territory, and 71 free Black people. However, counting the known enslaved people living in military forts in the territory, Nebraska had far more enslaved people than Kansas at the time.

Early newspapers reported that in Omaha, “Nearly all the federal office holders were from the south and they brought with them a negro slave or two as servants.” A Southerner named Edward K. Hardin was appointed as one of the United States judges for the territory and came to Omaha in 1854 with his “colored body servant,” a euphemism for an enslaved person.

Here are the identities of known enslaved people who were in Nebraska after the territory began and before slavery became illegal in 1861.

- (1854-1860) Enslaved people, names and number unknown, in Omaha

- (c.1854-c.1860) Enslaved person, name and age unknown, owned by James C. Mitchell in Florence

- (c.1854-c.1860) Enslaved person, name and age unknown, owned by James C. Mitchell in Florence

- (c.1854-c.1860) Enslaved person, name and age unknown, owned by James C. Mitchell in Florence

- (c.1854-c.1860) Enslaved person, name and age unknown, owned by James C. Mitchell in Florence

- (1854-18??) Enslaved people, names and number unknown, owned by Charles F. Holly in Nebraska City

- (1855-1857) Enslaved man, owned by Mark W. Izard in Omaha

- (1855) Enslaved man, owned by Charles A. Goshen in Nebraska City

- (1858) Hercules, man owned by Judge Charles Holly in Nebraska City

- (1858) Martha or Dinah, woman owned by Judge Charles Holly in Nebraska City

- (1858) Enslaved woman, name and gender unknown, owned by Robert Kirkham in Nebraska City

- (1860) Shade or Shale (?), man owned by Stephen Nuckolls in Nebraska City

- (1860) Shack Grayson, man owned by Stephen Nuckolls in Nebraska City

- (1860) Eliza Grayson (1840-????), woman owned by Stephen Nuckolls in Nebraska City

- (1860) Celia, woman owned by Stephen Nuckolls in Nebraska City

- (1860) Enslaved man owned by Stephen Nuckolls in Nebraska City

- (1857) Edie Hampton (?) owned by Ezra Nuckolls in Nebraska City

- (1852) Harding Hampton (1849-1922) owned by Ezra Nuckolls in Nebraska City

- (1852) Enslaved woman, daughter of Edie Hampton, sister of Harding Hampton, name unknown, owned by Ezra Nuckolls in Nebraska City

- (1852) Enslaved person, name unknown, owned by Ezra Nuckolls in Nebraska City

- (1852) Enslaved person, name unknown, owned by Ezra Nuckolls in Nebraska City

- (1860) Enslaved person, name unknown, owned by Alexander Majors in Nebraska City

- (1860) Enslaved person, name unknown, owned by Alexander Majors in Nebraska City

- (1860) Enslaved person, name unknown, owned by Alexander Majors in Nebraska City

- (1860) Enslaved person, name unknown, owned by Alexander Majors in Nebraska City

- (1860) Enslaved person, name unknown, owned by Alexander Majors in Nebraska City

- (1860) Enslaved person, name unknown, owned by Alexander Majors in Nebraska City

The tension about enslavement in Nebraska was palpable, and in 1858 it took a new form. Rebellious pro-slavery radicals from Otoe and Cass Counties wanted to suceed from their counties and form a new one called Strickland County where slavery would be legal and promoted. After this was put down by the territorial legislature, a group of legislators banded together to promote “South Platte,” meaning anything in Nebraska south of the Platte River, becoming annexed to Kansas. While this proposal failed, the notion of the South Platte counties being pro-slavery and anti-Black stayed for decades after.

However, at the same time, freedom seekers were moving along the Lane Trail through the South Platte in significant numbers.

III. Media Manipulation

Early Nebraska newspapers openly identified as either Republican or Democrat, which was a signal for anti-slavery or pro-slavery. Their morals were obvious in what news was printed in the papers, and how they referred to enslaved and free Black people.

In 1859, the Daily Nebraskian newspaper reported that it favored slavery: “The bill introduced in [Omaha City] Council, for the abolition of slavery in this Territory, was called up Yterday [sic], and its further consideration postponed for two weeks. A strong effort will be made among the Republicans to secure its passage; we think, however, it will fail. The farce certainly cannot be enacted if the Democrats do their duty.”

An anonymous article called “Nebraska and the N—–” was printed in the Nebraska City News in 1860. Condemning Republicans for trying to end slavery in the territory, the writer asked, “Have either of you ever been injured by slavery in Nebraska?” and “Have any of you any fear that you will be injured from that source?”

These were typical of pro-slavery newspapers in this era.

Dr. George Miller started the Omaha Daily Herald in 1865. Before that he served in the Nebraska Territory Legislature and shared his pro-slavery view that slavery simply didn’t exist in the territory. Never an Abolitionist, he was an American nationalist and established the Nebraska Regiment to go fight rebel states in 1860. Today, he is remembered with a park, school and neighborhood in North Omaha named after him. His newspaper continues operating today as the Omaha World-Herald.

It was 1860 when the Nebraska City newspaper published a demand that the territory ban Black people entirely by printing, “Cannot this be kept sacred as a home for white men – a field for white labor…?”

IV. Slaves for Army Officers

There were enslaved people at Fort Kearny near Nebraska City from 1844 to 1848, and then when the base was moved to the present-day city of Kearney, there continued to be enslaved people there from 1848 to 1863. They were owned by officers at the fort, who were assumed to be southern. Slavery there ended in 1861 when it became illegal in Nebraska. In the 1860 US Census, there were several enslaved people at the second Fort Kearny. Following is a list of known enslaved people at Army installations in Nebraska.

- (1820-1827) Enslaved people, names and number unknown, at Fort Atkinson

- (1844-1848) Enslaved people, names and number unknown, at the first Fort Kearny

- (1860) Mary Cheroot, age 45 from Missouri at Fort Kearny

- (1860) Mary Badeau, age 35 from Missouri at Fort Kearny

- (1860) Henry Cheroot, age 10 from Missouri at Fort Kearny

- (1860) Charlotte, age 26 from Missouri at Fort Kearny

- (1860) James, age 15 from Missouri at Fort Kearny

- (1860) Jane Steele, age 31 from Kentucky at Fort Kearny

- (1860) Israel, age 14 from Florida at Fort Kearny

- (1860) Jane, age 18 from Kentucky at Fort Kearny

V. Formerly Enslaved People in Nebraska

Additionally, there were many formerly enslaved people living throughout Nebraska after the Civil War. Some of the most notable included:

- Sallie Sylvester (1812-1920), Omaha—Oldest person in Omaha when she died at 108

- S.J. “July” Miles (1849-1941), Omaha—Oldest surviving African American Civil War veteran in Nebraska when he died

- Robert Ball Anderson (1843-1930) of Box Butte County—Largest Black land holder in Nebraska when he died

- Anderson Bell (1838-1903) of Omaha—Civil War veteran and longtime Omaha resident

- Richard D. Curry (1831-1885) of Omaha—Businessman, politician, community leader

- George W. Mattingly (1841-1924) of Butler County—

- Josiah “Professor” Waddle (1849-1939) of Omaha—Local musician and band leader

- Lewis Washington (1800-1898) of Omaha—Abolitionist speaker and local political activist

- John Flanagan (1791-1905) of Omaha—Oldest person in Nebraska he she died at 114

- Phillip King (1822-1888) of Omaha—

- Thomas Brown (1829-1923) of Omaha—

- Edwin Overall (1835-1901) of Omaha—Local Civil Rights advocate and government worker

- Frank Walker (1813-1915) of Omaha—Local real estate holder

- William R. Gamble (c.1850-1910)—Local community leader

- Cyrus D. Bell (1848-1925)—Local lawyer and political leader

- Archie Richmond (1838-1893)—Longtime print machine operator at the Omaha Bee

- Lizzie Robinson (1860-1945) of Omaha—Congregation starter for the Church of God in Christ

- Ophelia Clenlans (c1841-1907) of Omaha—Local political activist and community leader

- Joseph E. Payne (1861-1936) of Omaha—

- John Taylor (1847-1912) of Omaha—Said to be the “only slave” in Omaha when he died

- George Conway (1847-1939) of Omaha—Served Ulysses S. Grant after enslavement

When they arrived in the city, other formerly enslaved people made names for themselves. Archie Richmond worked for the Omaha Bee as a longtime print machine operator and was recognized as vital to the city’s newspaper industry. Bill Gamble was a community leader and Frank Walker owned substantial amounts of real estate. Cyrus Bell was a successful lawyer and political leader, and Ophelia Clenlans was an activist and community leader, too. The Church of God in Christ had several congregations opened by Lizzie Robinson, a longtime successful church-starter for them. Some of the oldest people in Omaha were formerly enslaved, including Lewis Washington who was 98 when he died in 1898; John Flanagan who died at 114 in 1905; and Sallie Sylvester who died at 108 in 1920.

There were literally hundreds of other formerly enslaved people who lived in Omaha; the people shared above were noted in the newspapers and from other sources. Their stories are fascinating though and should be explored more.

VI. Stalemate for Statehood

“But the fact is indisputable. African slavery does practically exist in Nebraska. Our eyes can not deceive us, and if slavery is wrong, morally, socially, or politically, it is wrong to hold one slave. There is no distinction in principle between holding one human being in bondage and ten thousand.”

—William H. Taylor, legislator from Otoe County in 1855

It was 1861 before the Nebraska Territorial Legislature voted to make slavery illegal. President Abraham Lincoln made the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 to free all enslaved people in the United States, and two years later the eleven rebel states were forced to do the same by losing the Civil War. It took six years for Nebraska to become an anti-slave state. Before that, there were no fewer than 10 votes on anti-slavery legislation that did not pass.

J. Sterling Morton (1832-1902) is a revered Nebraska statesman and founder of National Arbor Day. He was also a deep racist who stood devoutly dedicated to white supremacy, for enslavement, against equality, and with the South before and after the Civil War. Summarizing his beliefs in 1865 he wrote, “It will be more manly to accept negro suffrage by legal enforcement than to humiliate ourselves by its voluntary adoption as the price of admission to the Union… We take n—–s only when forced to it by Congress and therefore are for remaining at present a territory.”

[Adam’s Note: To illustrate the pungent nature of white supremacy, Morton wrote the first school book about the history of Nebraska, used for more than 75 years to teach the state’s history. Guess what topic and which people aren’t mentioned in the 362 page book?]

For more than a decade, racism prevented the Nebraska Territory from becoming a state. Congress refused to grant statehood while the state’s constitution made African American suffrage illegal. With the end of the Civil War, on February 20, 1867, territorial Governor Alvin Saunders called a special session of the legislature to strike the word “white” from the draft state constitution. This allowed for Black Nebraskans to vote, own land, hold political office, and otherwise become citizens. President Andrew Johnson signed a proclamation granting Nebraska statehood on March 1, 1867. Nebraska was the first and only state to grant suffrage to Black men under a specific mandate imposed by Congress.

VII. Remembering Slavery in Nebraska Today

All of this shows us that at least 50 people experienced slavery in Nebraska before it was made illegal in 1861. It also proves my point:

It’s not so much that there weren’t slaves in Nebraska, it’s that white people—including politicians, historians, government workers and teachers—have denied and neglected to see them throughout the entire history of Nebraska.

-Adam Fletcher Sasse

Today, slavery is called “human trafficking,” and it happens across the entire state. There are government task forces, nonprofits, and university programs focusing on the issue, and more needs to be done.

In 2023, Nebraska City’s main enslaver Stephen Nuckolls continues to be celebrated as the namesake of Nuckolls County, Nebraska, and of Nuckolls Square Park in Nebraska City. Rabid racist pro-enslavement politician John C. Calhoun (1782-1850) still has a town in Nebraska named for him, and many of the early pro-slavery legislators in Nebraska have counties, towns, schools and more named for them.

Meanwhile, there is no monument, placard or historical marker in Nebraska related to the role of either enslaved people or formerly enslaved people in building the state of Nebraska, including Omaha, Lincoln, Grand Island, North Platte, Valentine, or Nebraska City, as well as the dozens of other towns and counties where they lived.

Special thanks to Michaela Armetta, Ryan Roenfeld and Creola Woodall for their assistance with this article!

You Might Like…

MY ARTICLES RELATED TO ENSLAVEMENT IN NEBRASKA

Formerly Enslaved People: Robert Ball Anderson | Anderson Bell | Edwin Overall | Josiah “Professor” Waddle | Lewis Washington |

Pro-Slavery People: George Miller

Related Articles: Underground Railroad in Nebraska

MY ARTICLES ABOUT CIVIL RIGHTS IN OMAHA

General: History of Racism | Timeline of Racism

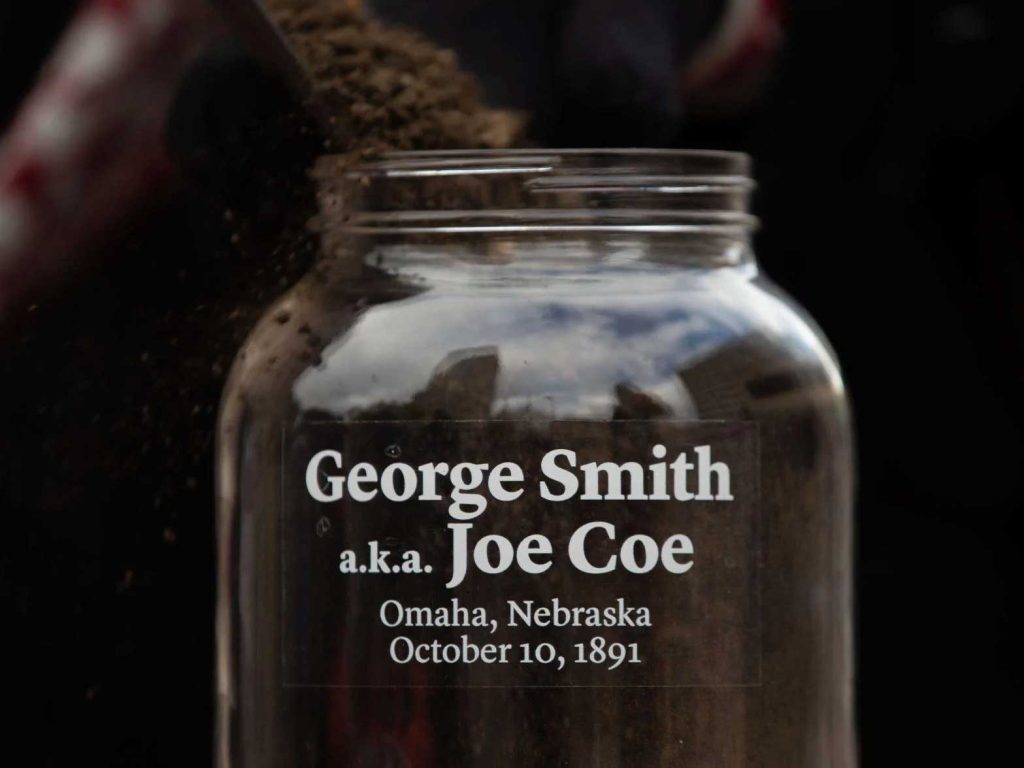

Events: Juneteenth | Malcolm X Day | Congress of White and Colored Americans | George Smith Lynching | Will Brown Lynching | North Omaha Riots | Vivian Strong Murder | Jack Johnson Riot | Omaha Bus Boycott (1952-1954)

Issues: African American Firsts in Omaha | Police Brutality | North Omaha African American Legislators | North Omaha Community Leaders | Segregated Schools | Segregated Hospitals | Segregated Hotels | Segregated Sports | Segregated Businesses | Segregated Churches | Redlining | African American Police | African American Firefighters | Lead Poisoning

People: Rev. Dr. John Albert Williams | Edwin Overall | Harrison J. Pinkett | Vic Walker | Joseph Carr | Rev. Russel Taylor | Dr. Craig Morris | Mildred Brown | Dr. John Singleton | Ernie Chambers | Malcolm X | Dr. Wesley Jones | S. E. Gilbert | Fred Conley |

Organizations: Omaha Colored Commercial Club | Omaha NAACP | Omaha Urban League | 4CL (Citizens Coordinating Committee for Civil Rights) | DePorres Club | Omaha Black Panthers | City Interracial Committee | Providence Hospital | American Legion | Elks Club | Prince Hall Masons | BANTU | Tomorrow’s World Club |

Related: Black History | African American Firsts | A Time for Burning | Omaha KKK | Committee of 5,000

MY ARTICLES ABOUT BLACK HISTORY IN OMAHA

MAIN TOPICS: Black Heritage Sites | Black Churches | Black Hotels | Segregated Hospitals | Segregated Schools | Black Businesses | Black Politics | Black Newspapers | Black Firefighters | Black Policeman | Black Women | Black Legislators | Black Firsts | Social Clubs | Military Service Members | Sports

PIONEER BLACK OMAHA: Black People in Omaha Before 1850 | The First Black Neighborhood | Black Voting in Omaha Before 1870 | Racist Laws Before 1900 |

EVENTS: Stone Soul Picnic | Native Omahans Day | Congress of Black and White Americans | Harlem Renaissance in North Omaha

RELATED: Race and Racism | Civil Rights Movement | Police Brutality | Redlining

NEBRASKA BLACK HISTORY: Enslavement in Nebraska | Underground Railroad in Nebraska | Grand Island |

TIMELINES: Racism | Black Politics | Civil Rights | The Last 25 Years

RESOURCES: Book: #OmahaBlackHistory: African American People, Places and Events from the History of Omaha, Nebraska | Bibliography: Omaha Black History Bibliography | Video: “OmahaBlackHistory 1804 to 1930” | Podcast: “Celebrating Black History in Omaha”

Sources

- “Nebraska Historical Marker: Mayhew Cabin, 1855” by History Nebraska

- Nebraska Advertiser newspaper archives (Brownville, NE: 1856-1882)

- Nebraska Palladium newspaper archives (Bellevue: 1854-1855)

- Bellevue Gazette newspaper archives (Bellevue: 1856-1858)

- Dakota City Herald newspaper archives (Dakota City: 1857-1860)

- “Slavery in Nebraska” by Edson P. Rich for the Nebraska State Historical Society in 1887

- “How Eliza Grayson escaped Nebraska slavery,” by David Bristow for History Nebraska

- Chapter XX “Slavery in Nebraska” by J.S. Morton in History of Nebraska from the Earliest Explorations of the Trans-Mississippi Region, pg 449-463 from 1918

- “Was He, or Wasn’t He? A Case of Mistaken Identity” by Gail Shaffer Blankenau for Discover Family History on August 11, 2020

- “Journey to Freedom: Graduate thesis addresses slavery in Nebraska Territory,” by Tyler Ellyson for UNK News on April 12, 2021

- “Todd, John” in the Biographical Dictionary of Iowa at the University of Iowa

- “Fact and Folklore in the Story of ‘John Brown’s Cave’ and the Underground Railroad in Nebraska” by James E Potter for Nebraska History 83 in 2002, pgs 73-88

- “Necessary Courage: Iowa’s Underground Railroad In The Struggle Against Slavery” by Lowell J. Soike in 2013

- “Slavery in Nebraska” by Addison Erwin Sheldon in History and Stories of Nebraska in 1914 for the University Publishing Company

- “History of slavery in Nebraska,” Wikipedia

MORE

Leave a Reply