The history of African Americans in Nebraska is a rich, complex story that is defined by ongoing themes of resilience, struggle, and Black excellence against a backdrop of white supremacy, systemic racism and racial violence. It is a story woven into the very fabric of the state that challenges the myth of a purely white, progressive Western frontier.

Foundations: Slavery, The Frontier, and Community Roots

The presence of Black people in the land that became Nebraska predates America, and might start with Spanish explorations in the future state in the 16th century by people like Estevanico in 1539.

As the territory formed, the issue of chattel slavery was immediate and contentious. Despite the Missouri Compromise intending for the land to be free, enslaved persons were brought in by military officers at places like Fort Atkinson and Fort Kearny, as well as by territorial founders like Stephen F. Nuckolls (1825-1879) in Nebraska City.

Before and during the Civil War, the Underground Railroad actively ran through southeastern Nebraska, with Abolitionists helping an unknown number of freedom seekers like Eliza Grayson (1832-??) escape north along the Jim Lane Trail. The struggle over the issue was finally resolved when the Nebraska Territorial Legislature voted to make slavery illegal in 1865.

Following the Civil War, Black community life in Nebraska rapidly formalized. St. John’s African Methodist Episcopal Church, established in Omaha in 1865, is the state’s oldest Black congregation. Secular organizations followed statewide, including the Prince Hall Masons, co-founded by Richard D. Curry in 1866, which provided essential social and fraternal networks.

Beyond the major cities, Black settlers established numerous towns and enclaves across the state in pursuit of land and autonomy, such as Grant in Franklin County and Overton in Dawson County. The most notable and longest-lasting was DeWitty (later Audacious) in Cherry County, established in 1904, settled largely by formerly enslaved persons, their descendants, and Black Canadians. However, facing marginal land, drought, and economic hardship, these rural communities ultimately declined, and by the 1930s, the state’s Black population became heavily concentrated in Omaha and Lincoln.

Economic Life, Opportunity, and Disparity

From the earliest days, Black residents carved out economic niches, often filling roles rejected by or denied to white laborers. In 1856, Bill Lee opened Omaha’s first Black business, a barbershop. In Grand Island, Wilford Goodchild (1842-1879) established himself as the first Black barber, while his brother Thomas became the first African American firefighter in Nebraska. The railroad industry, which expanded rapidly after the Civil War, became an important source of Black employment statewide, with Black men serving as porters and laborers—positions that, along with hotel bellhops, often symbolized middle-class respectability in a segregated world.

Black entrepreneurs also led efforts to address systemic economic disenfranchisement. The earliest examples of this came in the 1870s when Black business owners in Omaha established “leagues” and other arrangements to serve Black customers. The first labor union in Nebraska was started in Omaha in 1887, and was organized by African American barbers. In addition to serving the Black community, African American entrepreneurs and businesspeople also served white customers.

After more than a dozen Black newspapers were started in the 50 years prior, in 1938, Mildred Brown (1905-1989) founded the Omaha Star to serve the entire state. During the same era, as white banks continued to deny capital and services to Black families, community leaders established the Carver Savings and Loan Association in 1944 in North Omaha to provide mortgages, savings accounts, and checking services to its members.

Despite these efforts, white supremacy and systemic racism were among the external forces that constantly undermined Black economic stability in Nebraska. The Great Depression reinforced the adage of “last hired, first fired” for Black workers. Moreover, federal policies codified economic apartheid, first with the US Army starting Omaha’s redlining practices in 1919, then with the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) mapping out residential areas occupied by Black people as “dangerous” in 1936, thereby formalizing redlining in Omaha and Lincoln and denying loans, insurance, and investment. This structural discrimination contributed directly to reports showing Omaha having extremely high rates of Black poverty and deep economic disparity by 2007.

Systemic Racism and Violent Suppression

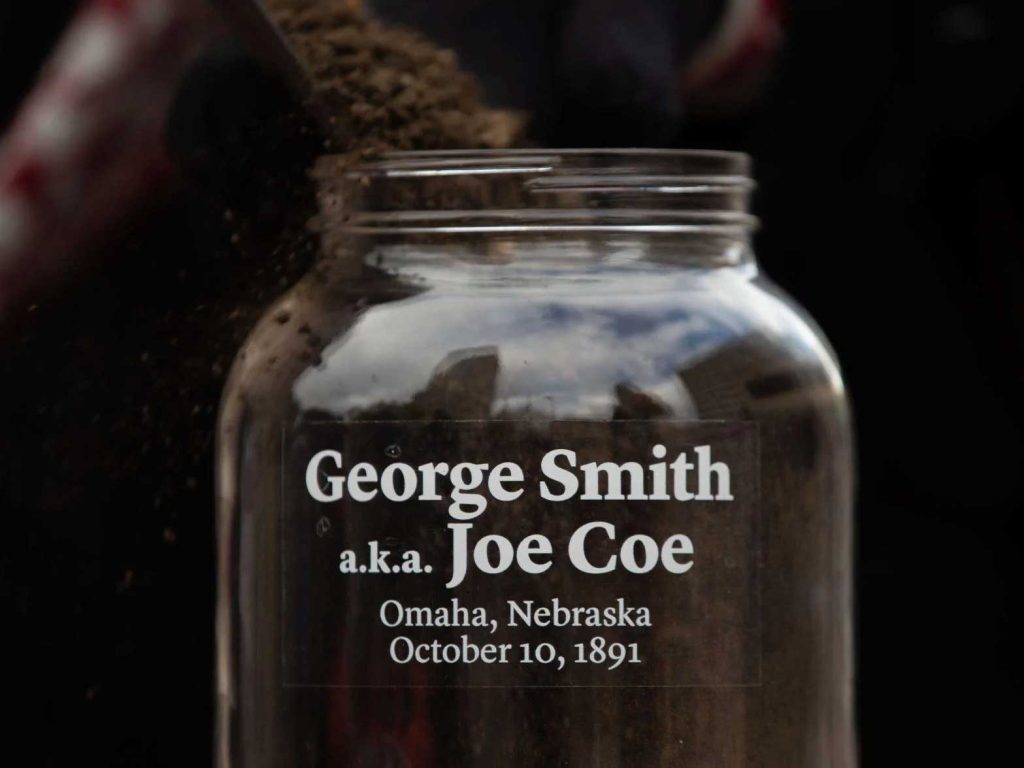

African American history in Nebraska is tragically marked by horrific racial violence and pervasive state-sanctioned racism. The state witnessed multiple public lynchings of Black men, including Henry Jackson and Henry Martin (1878), George Smith (1891), and Will Brown (1919) in Omaha, as well as Jerry White (1887) in Valentine and Louis Seeman (1929) in North Platte. The lynching of Will Brown triggered the Omaha Race Riot, leading the U.S. Army to impose martial law and explicitly decree a “Black Belt” area of containment in North Omaha for Black residents—a formal act of segregation by the federal government.

Institutional racism was equally devastating. Nebraska upheld miscegenation laws forbidding interracial marriage until 1963. Segregated schools were an early fact of life. The political arm of white supremacy, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), saw an explosive growth period in the 1920s, boasting up to 45,000 members across the state and using cross burnings and parades to spread terror and demand Jim Crow policies.

Later, local and federal government initiatives in Nebraska further undermined Black life, including the construction of the North Freeway in the post-Civil Rights era decimated over 1,000 Black homes, churches, and businesses in North Omaha, physically bisecting the community.

Finally, systemic police brutality against Black citizens became a consistent source of tension and a spark for the riots of the mid-1960s, a theme that tragically extended into the modern era.

The Fight for Civil Rights and Legislative Power

The fight for Civil Rights in Nebraska spans two centuries, evolving from quiet political organizing to mass direct action.

After statehood, Edwin Overall (1835-1901) successfully agitated for the desegregation of Omaha’s public schools in 1871. After at least two decade of Black political organizing in Nebraska, in 1893, Dr. Matthew O. Ricketts (1858-1917) became the first African American elected to the Nebraska Legislature. The National Afro-American League and the United Negro Improvement Association, as well as the Omaha chapters of the NAACP (founded 1918) and the Urban League (founded 1927), established formal, organized opposition to discrimination in housing, jobs, and education.

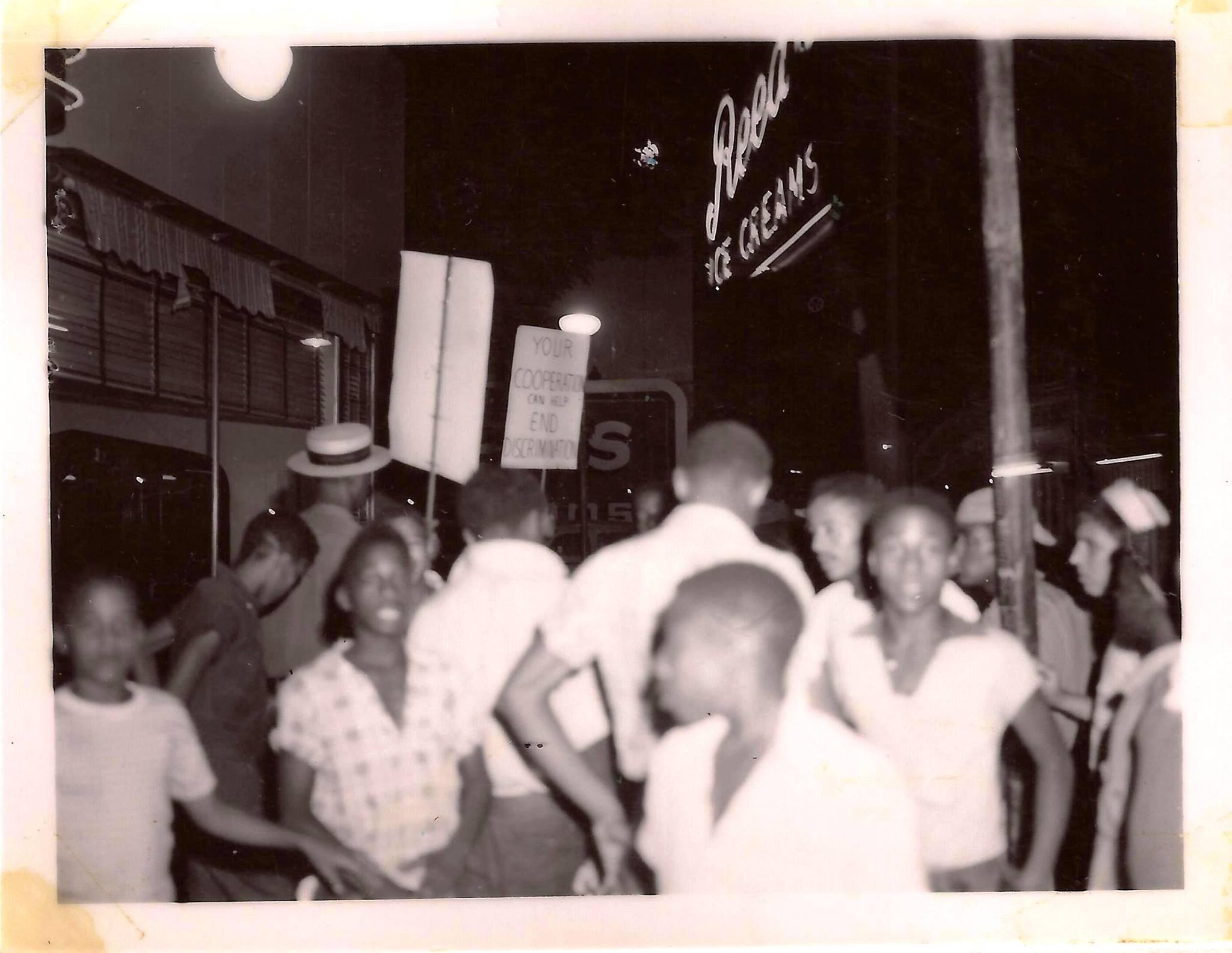

The direct-action phase of the Civil Rights movement in Omaha began in 1947 with the biracial student-led Omaha DePorres Club. This was soon amplified by groups like the Citizens Coordinating Committee for Civil Liberties (4CL) in 1963, which engaged in nonviolent protests that successfully led to the desegregation of Omaha’s Peony Park swimming pool and much more. 4CL brought Malcolm X back to his hometown of Omaha in 1964, providing a profound moment of Black consciousness. The legislative progress, spurred by this activism, included the Nebraska Civil Rights Act of 1969.

With more than a dozen African American legislators elected to the state’s legislature since Dr. Matthews, the most formidable legislative power in the state’s history ever belonged to Senator Ernie Chambers of North Omaha, who began his record-setting tenure in 1971. A constant enemy of institutional racism statewide, Chambers is credited with numerous major victories, including ending corporal punishment in schools and leading Nebraska to become the first state to pass legislation calling for divestment in apartheid South Africa.

Elizabeth Davis Pittman (1921-1998) shattered barriers, becoming the Nebraska’s first Black female lawyer and later its first Black and first female judge in 1971. Fred Conley and Brenda Council opened doors on the Omaha City Council, with Council becoming one of the first two Black women elected to the Legislature in 2009.

Cultural Resilience and Modern Contributions

Throughout every era of oppression, the Black community in Nebraska expressed powerful resilience and Black excellence through culture and professional achievement. The early 20th century saw the height of the Black jazz scene in Omaha, launching artists like Maceo Pinkard (1897-1962) and producing leaders like Dan Desdunes (1870-1929). The Harlem Renaissance extended to Nebraska through figures like visual artist Aaron Douglas (1899-1979), an early graduate of UNL, and the pioneering Black female newspaper publisher, Mildred Brown.

Black people from Nebraska served in every American conflict, notably the Buffalo Soldiers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and the Tuskegee Airmen during World War II, including pilot Alfonza W. Davis (1919-1944). In sports, UNL’s George Flippin (1868-1929) pioneered integration in collegiate athletics despite intense racism in the 1890s.

The Nebraska Black athletic tradition extends for decades in a dozen sports. In the 1950s, Omaha produced national stars like Bob Gibson (1935-2020), Gale Sayers (1943-2020), and Heisman winner Johnny Rodgers.

In music, Omaha native Terry Lewis became a multi-Grammy-winning songwriter and producer, reaching the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

The preservation of this deep history was institutionalized by Bertha Calloway (1925-2017), who founded the Great Plains Black History Museum in 1976. Rowena Moore (1910-1998) founded the Malcolm X House Site and Memorial Foundation in 1971, ensuring that the legacy of Omaha’s native son is recognized. These institutions stand as testaments to the continuous, powerful, and enduring African American legacy that shapes Nebraska’s identity.

Understanding History

The history of African Americans in Nebraska began centuries ago with early explorers and enslaved individuals, followed by pioneers who settled the territory. Despite the abolition of slavery in 1861, Black communities have continued to endure persistent systemic racism, facing decades of violence, discriminatory Jim Crow laws, and challenges to their political rights and rural settlements. Through sustained struggle and organizing, African Americans established vital political, religious, and cultural institutions, successfully leading civil rights movements and electing groundbreaking leaders, thereby forging a lasting legacy of entrepreneurship and cultural excellence primarily centered in the state’s major cities.

Long accounts, deep insights, ongoing legacies and overarching themes come through in every part of Nebraska’s Black history. It is important for every Nebraskan to learn about this history beyond its superficial roots by exploring this depth, learning these meanings and examining its relevance to our own lives everyday, in every way we can imagine. Only then can Nebraska truly be the good life for everyone.

Special thanks to the Institute for Urban Development and Preston Love, Jr. for supporting the research behind this article.

You Might Like…

NEBRASKA BLACK HISTORY

Communities: A History of African Americans in Grand Island

Other: A History of Enslavement in Nebraska | A History of the Underground Railroad in Nebraska

MY ARTICLES ABOUT BLACK HISTORY IN OMAHA

MAIN TOPICS: Black Heritage Sites | Black Churches | Black Hotels | Segregated Hospitals | Segregated Schools | Black Businesses | Black Politics | Black Newspapers | Black Firefighters | Black Policeman | Black Women | Black Legislators | Black Firsts | Social Clubs | Military Service Members | Sports

PIONEER BLACK OMAHA: Black People in Omaha Before 1850 | The First Black Neighborhood | Black Voting in Omaha Before 1870 | Racist Laws Before 1900 |

EVENTS: Stone Soul Picnic | Native Omahans Day | Congress of Black and White Americans | Harlem Renaissance in North Omaha

RELATED: Race and Racism | Civil Rights Movement | Police Brutality | Redlining

NEBRASKA BLACK HISTORY: Enslavement in Nebraska | Underground Railroad in Nebraska | Grand Island |

TIMELINES: Racism | Black Politics | Civil Rights | The Last 25 Years

RESOURCES: Book: #OmahaBlackHistory: African American People, Places and Events from the History of Omaha, Nebraska | Bibliography: Omaha Black History Bibliography | Video: “OmahaBlackHistory 1804 to 1930” | Podcast: “Celebrating Black History in Omaha”

Elsewhere Online

- Great Plains Black History Museum

- North Omaha Visitors Center

- “A History of African Americans in Nebraska” by Preston Love, Jr., Adam Fletcher Sasse, et al. (2025).

BONUS

Leave a Reply