In 2023, North Omaha is a food desert where there are too few places for residents to buy healthy groceries. However, there was a time when grocery stores dotted every neighborhood in corner stores and bigger facilities. A few of them, including this one, was a Black-owned business. This is a history of the Garden Market located in the Kountze Place neighborhood from 1948 to 1976.

Starting a Market

Between 1912 and 1926, a strip of commercial buildings were built along Florence Boulevard from Emmet Street to Pinkney Street.

One day in 1947, the BDJ Ice Cream Shop, located at 3419 Florence Boulevard in the Kountze Place neighborhood, had a break-in where thieves stole equipment, ice cream, candy and gum, along with money. The owner was frustrated and almost immediately put up the entire operation for sale. The business didn’t sell though. Situated in a small business strip with an apartment above it, the property stayed on the market for a year. Nobody knew the space would next be a grocery for nearly 30 years.

In September 1948, Meyer Meyerson (1890-1981) and Bernard Kaufman (1911-1972) opened the Garden Market at 3419 Florence Boulevard. Buying the entire business block, the market had a small parking lot to the south and was a large neighborhood grocery store. Originally part of the United Grocery Store chain, the store was well-lit with the latest in grocery store innovations, there was an in-house meat shop, a huge selection of canned and boxed goods, and a large fresh produce section fitting its name.

Growing Pains

The business was successful and grow popular in the community. Even as white flight swept through the Kountze Place neighborhood, the surrounding area including white and Black customers carried the market and ensured its success.

After humming along for a few years, starting in 1953 the Garden Market was hit by a series of small calamities. In March, there was a burglary that led to almost $250 in losses. Later that same month, the store was hit by a fire at the rear of the building. Stacks of coffee, bleach and other merchandise burned up. Firemen reported that heat in a rear storage room was high enough “to cook several cartons of eggs.” There was “several thousand dollars” worth of damage. Although it wasn’t cited as a reason, the article did mention that a new air conditioner was installed earlier in the week. Owner Meyerson estimated the damage would be covered by his business insurance.

In January 1954 another fire struck the store, apparently as an inside job. The Omaha Fire Department’s arson bureau found the back door had been unlocked and opened from inside without force by someone who hid in a rear storage room. After starting the fire, they escaped with a butched knife, using it to take the back door hinges off. The fire was found after midnight. The second fire was started near where the first happened. The newspaper reported, “Smoke and water damage was extensive throughout the store but the fire damaged only the storeroom and roof.” Reportedly spending $500 on repairs, the store chugged along afterward.

The store was held up in June 1957, with the robbers getting about $168 in loot. Owner Meyerson chased the man with a gun, but the robber got away in a waiting car. Another thief was thwarted in Feburary 1960 though, when they were apparently scared away after smashing a window and gathering several bags of groceries. A month later, the perpetrators were found to be two 8-year-old boys. When it was found that the pair had vandalized two churches and an annex at Lothrop School, the case was studied by the Omaha World-Herald for weeks. Their vandalism was much more thorough than damage to the store though.

Myerson and his business partner added onto the store in May 1960, spending $18,000 to expand the rear of the structure. They also added the large parking lot to the north, effectively fronting the entirety of Florence Boulevard. They expanded again in 1963, this time building onto the south side of the building. This time they sold their old meat counter and bought new equipment, creating a modern, inviting environment in their store.

Stopping Racist Hiring Practices

Even though Black customers patronized the store, the store didn’t hire African American workers.

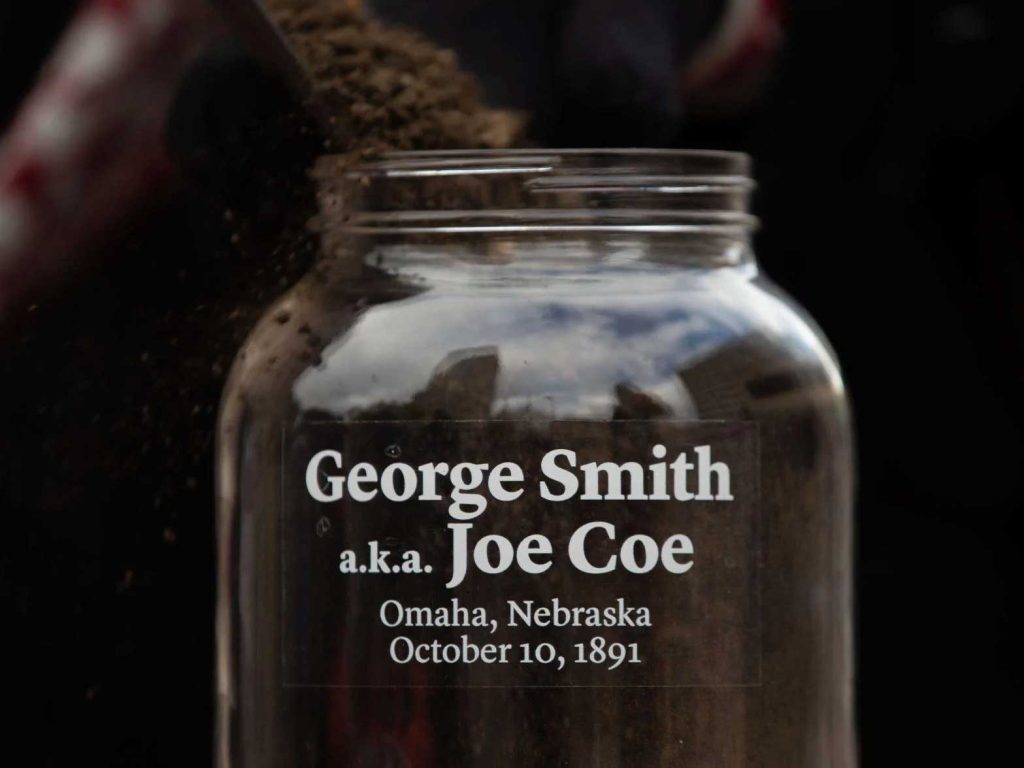

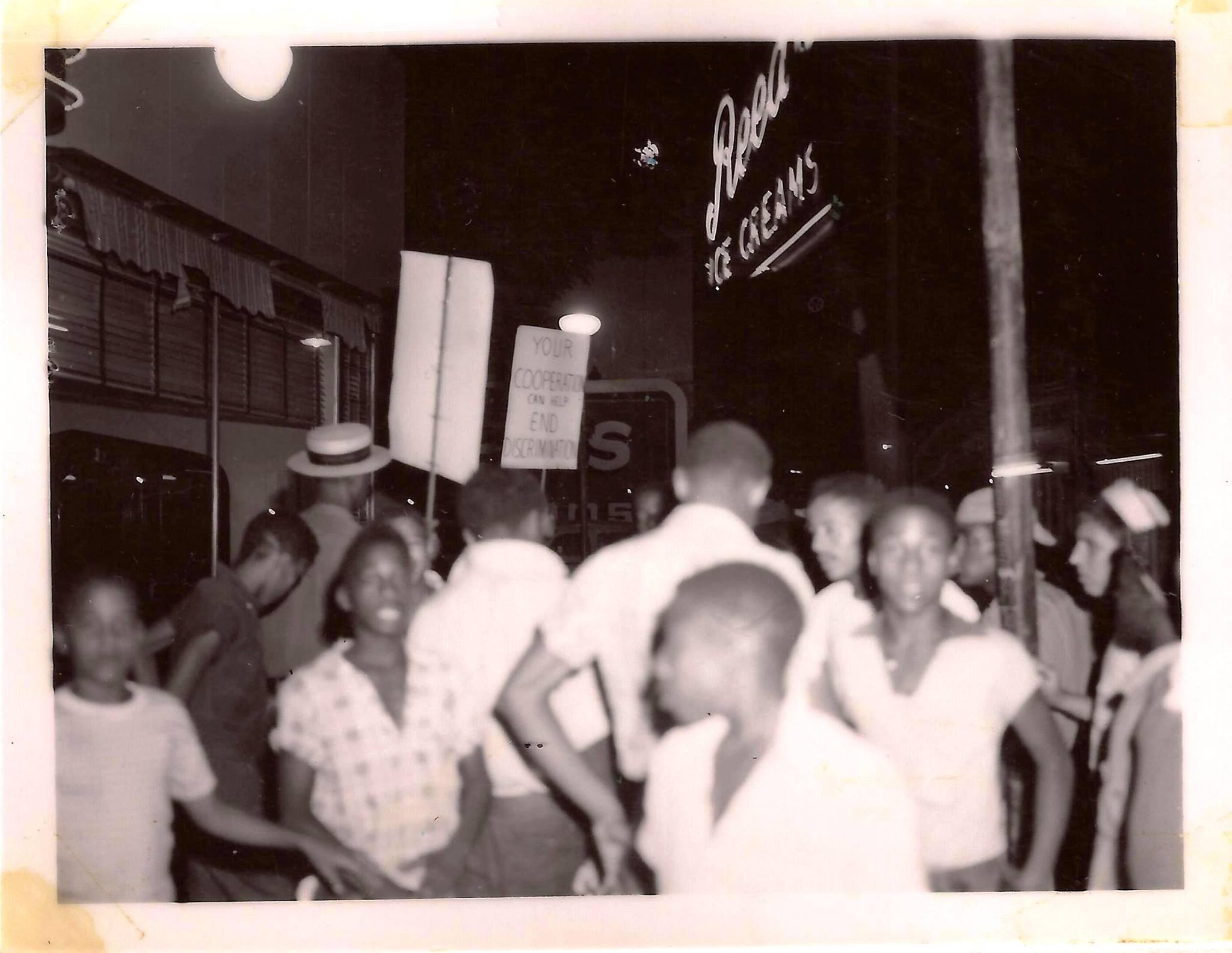

The Citizens Coordinating Committee for Civil Liberties, or 4CL, picketed the supermarket in July 1963. Additionally, the organization staged a “three-day selective patronage campaign” led by Rev. Rudolph McNair and Rev. Kelsey Jones. To resolve their protest, 4CL demanded the store hire Black workers at the store, which was previously exclusively white. After the supermarket hired five African American workers the 4CL called off their protest and declared success. They proceeded to move on Safeway and other stores afterward.

In 1964, the Garden Super Market received an order from the National Labor Relations Board after refusing collective bargaining with the local Retail Clerks International (AFL-CIO). The store, which employed 40 workers, apparently interrogated its employees about their union activities and was subject to a trial.

Changing Times

The store must have felt good about their prospects after that though, and later in 1964 they applied for rezoning to ensure their entire structure was zoned first commercial to make way for more expansion.

Bernard Kaufman, a co-owner of the store, was beaten and robbed at the store in 1967. In May of that year he went to his car to leave for the day at 9pm when a group of young men beat him and forced him back into the store at gunpoint. Commanding six workers to lay face down, they forced Kaufman to open the safe and robbed money. Meyerson, the other owner, offered a $200 reward the next day.

During the June 1969 riot, a group of people were arrested at the supermarket after looting it. Two of them kicked out the door of the paddy wagon they were riding in, but were later apprehended. Six people between the ages of 18 and 36 were charged with “feloniously entering a building with intent to steal,” and all pleaded innocent. The public defender argued five of the accused weren’t seen carrying anything from the market, and there was no evidence of felonious entry. The judge disagreed and ordered them to stand for trial. I couldn’t find the outcome of the trial.

There were more incidents at the store throughout 1969, including purse snatching, robberies and other illegal activities.

Becoming Kellogg’s

After filing incorporation papers in 1969, it was April 1970 when a 27-year-old African American named Marvin H. Kellogg (1942-2018) and his father Marvin E. Kellogg (1920-2008) bought the business from Meyerson and Kaufman. The younger Kellogg, called “Kelly,” was a grocery man who worked for 13 years in the store before buying it. A graduate from Central High School, he started working at the store when he was 14-years-old. He and his father went through a year of scrutiny from the Small Business Administration to secure a $130,500 loan which they were initially turned down for. However, they were eventually approved after securing an additional “$15,000 loan from American Savings Company, a $30,000 investment from Hinky Dinky Stores and the personal support of the late C.M. “Nick” Newman, then-president of Hinky Dinky,” according to a 1986 Omaha World-Herald article.

A store manager for three years before buying it, the younger Kellogg also completed a two-year business program at UNO. “Now I’m just starting to learn about the full responsibility of being a proprietor of a store. Owning my own store is just about the greatest thing that ever happened to Dad and me,” Kelly said in 1970 feature from the Omaha Star.

The World-Herald reported that former co-owner Meyer Meyerson made more than $1,000 monthly as a consultant to the market, along with $1,500 monthly to lease the building and the purchase price of $175,000. The paper also made note that Hinky Dinky officials were named directors of the new company.

Kellogg dealt with racism among his customers even before buying the Garden Market. “When a Black man goes into business,” he said to the Omaha World-Herald, “the first thing that happens is that customers look for a change. They look for the shelves to be bare and they expect you to have old stock.” To redress this discrimination, Kellogg didn’t tell customers he bought the store for some time after the purchase was completed.

Renamed Kellogg’s Garden Super Market and with high sales projected the first year totaling $2.5million, Kellogg anticipated expanding soon after. The Kelloggs employed 43 full-and part-time employees in 1970 and had six checkouts in the store. Kellogg’s father worked for Roberts Dairy and helped in the store at night.

In 1972, the elder Kellogg was quoted as saying “Our volume of sales has been good… Our clientele is both Black and white and our work force is about equally divided Black and white. So far, we’ve been happy with our business.”

However, in a 1986 interview, the younger Kellogg said business soured almost immediately as white people fled from the surrounding neighborhood and “many better-paid Blacks did the same.” The Kountze Place neighborhood lost almost half of its population in the 1970s and simply couldn’t sustain its own supermarket.

Unfortunate crimes kept happening at the supermarket after the sale. In late August 1970, a vendor was held up as he unloaded his wares at the store. A robber stole almost $125 in cash from the man, who escaped. Writing about the market, the newspaper said “Thievery was out of control.” They quoted Marvin Sr. as saying, “You could walk out on the floor at any time of day and find somebody stealing. Both customers and employees stole from us. We fired quite a few for it. I fired the leading produce man – a white – who was stealing cigarettes.”

Kellogg’s store joined the Spartan chain in 1973, leading to extended purchasing opportunities, and in 1974, Marvin H. Kellogg became the president of the Mid-City Business and Professional Association.

However, 1975 was a big blow to the Kellogg’s Garden Market, as the well-paying jobs at the meatpacking plants in South Omaha were lost permanently. Additionally, when the North Freeway demolished more than 1,000 homes many customers lost their homes and moved away.

In 1973, total gross sales at the store were $2.8million; in 1976, they were about $1million. That year, the Kelloggs closed their doors permanently. A decade after closing, Marvin H. Kellogg was quoted as saying that he learned not to go into business until you learn all the angles.

It was August 1976 when the newspaper carried an ad for the business’s going out of business liquidation. It announced that everything in the store would be sold for 50% off or more, and that “all stock must sell.”

Marvin E. Kellogg went to work for the U.S. Postal Service and retired in 1984. He died in 2008. Marvin H. Kellogg sold insurance and died in 2018.

After the Kellogg’s

The building stood for more than 45 years after Kellogg’s Garden Super Market closed.

It sat empty for more than a decade after Kellogg’s closed though. In 1979, a city councilman got excited when neighbors successfully protested a liquor license for a nightclub that wanted to open in the building. The newspaper excitedly said, “He said it was encouraging because it meant citizens were taking pride in their neighborhoods and is a sign the inner city is being rebuilt.”

It was 1989 when the building became the headquarters of the Nebraska Minority Contractors Association. The building was remodeled by the association membership, which was intended to represent “the needs of minority-owned, women-owned and small business contractors in the area.” Within the same year though, the building was featured in the media for gang graffiti that covered it. The association merged with another in 1993, and after 1990 its location was never mentioned in North Omaha again.

In 2001, a business called the Mother Goose Daycare opened at 3419 Florence Boulevard. It employed 10 people and earned about $210,000 annually, and closed around 2019.

The building was owned by Benny Valentine when it was demolished in 2019. Today the site sits empty with no sign of what was ever located there.

You Might Like…

MY ARTICLES ABOUT GROCERY STORES IN NORTH OMAHA

Summary: A History of Grocery Stores in North Omaha

Separate Stores: Kellogg’s Garden Super Market | Battiato’s Super Market | Fort Street Grocery Store | Forgot Store | 24th and Lake Safeway | Meckley & Myers | Omaha Market House | Jacobberger Groceries | Heath and Co. | Burstein-Runierman Grocery | Shaver’s Food Store | Paul Adams Grocery | Peterson’s Grocery | 24th and Ames A&P/Hinky Dinky

Briefs: New Market | Florence Field Grocery | 24th and Ames A&P | Kuppig Grocery | New Boulevard Market

Related: Bakeries | Restaurants | Drive-Ins

MY ARTICLES ABOUT THE HISTORY OF KOUNTZE PLACE

General: Kountze Place | Kountze Park | North 16th Street | North 24th Street | Florence Boulevard | Wirt Street | Emmet Street | Binney Street | 16th and Locust Historic District

Houses: Charles Storz House | Anna Wilson’s Mansion | McCreary Mansion | McLain Mansion | Redick Mansion | John E. Reagan House | George F. Shepard House | Burdick House | 3210 North 21st Street | 1922 Wirt Street | University Apartments

Churches: First UPC/Faith Temple COGIC | St. Paul Lutheran | Hartford Memorial UBC/Rising Star Baptist | Immanuel Baptist | Calvin Memorial Presbyterian | Trinity Methodist Episcopal | Mount Vernon Missionary Baptist | Greater St. Paul COGIC | Plymouth Congregational/Primm Chapel AME/Second Baptist | Paradise Baptist

Education: Omaha University | Presbyterian Theological Seminary | Lothrop Elementary School | Horace Mann Junior High | Omaha Presbyterian Theological Seminary

Hospitals: Salvation Army Hospital | Swedish Hospital | Kountze Place Hospital

Events: Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition | Greater America Exposition | Riots

Businesses: Hash House | 3006 Building | Grand Theater | 2936 North 24th Street | Corby Theater

Other: Kountze Place Golf Club

Listen to the North Omaha History Podcast show #4 about the history of the Kountze Place neighborhood »

BONUS

Leave a Reply to Adam F.C. FletcherCancel reply