In the history of Omaha, there are people who going along with the flow, people who challenge the ways things are, and people who actively struggle for change that benefits everyone. One African American woman’s struggle led to the Omaha Public Schools effort to integrate schools citywide. This is a biography of Nellie Mae Webb.

Raising a Family

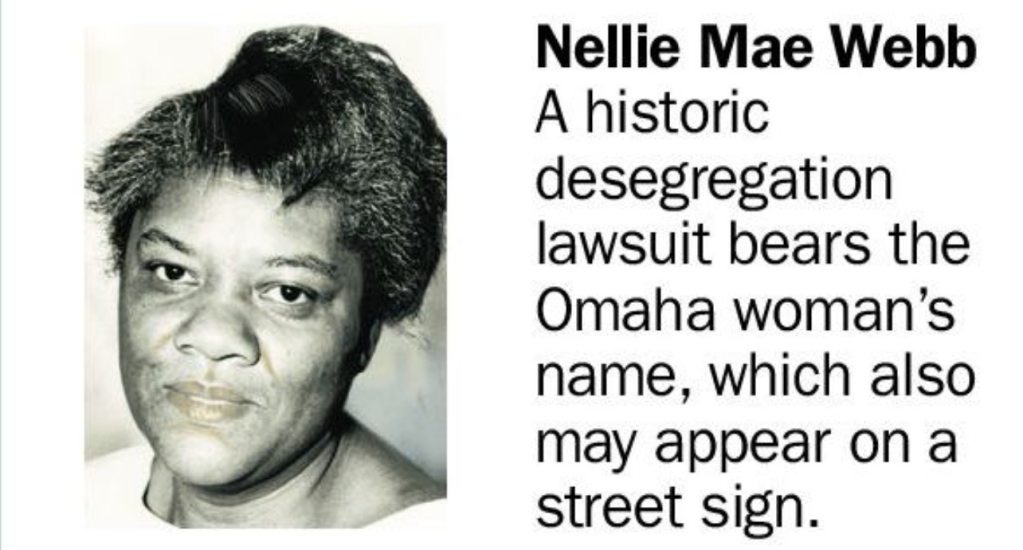

Nellie Mae Webb (1929-2002) was born in Omaha to Dan Wade, Sr. (1902-1977) and Etter Wade (1906-1935), the height of the city’s Jim Crow reality. Her family lived in the segregated Long School neighborhood, then referred to as the “Black Belt” of Omaha. After attending Tech High, she started her family and continued living in the community.

Ms. Webb had seven children. In a 2019 interview, one of her daughters said, “her mom kept a loving home. She always sacrificed for her kids, denying herself new clothes and shoes to ensure that the kids had what they needed, she said. She was always happy, and the key to the family[…] Her mother was always willing to listen to their problems[…] Though she couldn’t always solve them, she was ‘a shoulder to lean on.’”

Fighting a Racist System

According to her obituary, “Webb believed that the freedom Blacks achieved had not reached the classroom. She talked over the problem with other parents and attended community meetings.” After that and “ugly racial incidents” her own kids experienced, she and seven other parents decided to take action. Organizing alongside Lerlean Johnson (1932-2010), Zenolia Hilliard, Lillie Gunter, Irene Gunter, and her sister Charlotte Stropshire, Nellie Mae Webb held school district officials accountable and “took the next step.”

For 125 years before they organized, several schools in North Omaha were nearly exclusively where all the Black students in Omaha attended. Because of white supremacy baked into the education system, these buildings were constantly in poor condition, constantly underfunded, understaffed, overcrowded and under-performing.

The group of parents became formal intervenors on the plantiff’s side, and the U.S. Department of Justice sued Omaha Public Schools for racial discrimination in a trial called United States of America and Nellie Mae Webb et al. v. School District of Omaha. The 8th U.S. Ciruit Court of Appeals ruled in favor of the intervenors in 1975, and busing started in 1976. The court order made OPS use a plan to integrate schools until 1984; however, because white flight intensified so rapidly during those nine years, the district continue its integration plan until 1999.

“Getting to know one another has been a good thing,” said Ms. Webb in 1977. However, in 2019 one of Ms. Webb’s daughters told the Omaha World-Herald “the women who sued faced criticism, including threatening letters and phone calls.” Her mom… “played it off like it wasn’t such a big issue.”

“I remember my Aunt Charlotte had a whistle. And when they would call her, she would just blow the whistle in the phone,” the daughter said.

In 1980, Ms. Webb received an award along with the other intervenors at the Black Heritage Series by the Wesley Community United Methodist Church.

However, the activists weren’t deaf to reality, and by by 1991 members of the group were quoted saying they thought busing resulted in Black children being subjected to more mistreatment. “The Black children did most of the busing and they were not made to feel welcome or part of the school.” Ms. Webb was quoted as saying, “It is going to take more than assigning Black children to desks next to white children to make a difference in Black childrens’ lives.”

By the time it ended, Omaha’s school integration plan was viewed with mixed results. Data show that African American students were saddled with the burdens of busing, learning white culture and experiencing racism at every turn in their schooling, as well as facing the school-to-prison pipeline throughout Omaha Public Schools. Meanwhile, white Omahans continued withdrawing their children from schools in the district, including the so-called integrated schools where Black students attended.

In 1999, Omaha Public Schools received permission from the U.S. Supreme Court to end the integration program. “I’m glad it’s over,” and, “At the time it was worth trying. But I’m relieved it’s over,” Ms. Webb told the paper.

Refusing to Forget

Ms. Webb died in 2002. In 2019, the Omaha World-Herald wrote a feature about her and said, “You can’t talk about desegregation in Omaha without mentioning Nellie Mae Webb — her name is in the title of the 1973 lawsuit that forced the Omaha Public Schools to desegregate.”

Starting in the 1999-2000 school year, 75% of all OPS students attended neighborhood schools, and within a few years the district was racially segregated again. As of 2024 the district is more racially segregated than it was in 1973 when the court ordered integration.

Different from almost all Omahans, Ms. Webb dedicated much of her energy to fighting racism in Omaha Public Schools and lent her name to the federal lawsuit that forced the district to change. Today, there are no memorials named in honor of Nellie Mae Webb, and few in honor of the other intervenors in the case that changed Omaha schools.

You Might Like…

MY ARTICLES ABOUT THE HISTORY OF SCHOOLS IN NORTH OMAHA

GENERAL: Segregated Schools | Higher Education

PUBLIC GRADE SCHOOLS: Beechwood | Belvedere | Cass | Central Park | Dodge Street | Druid Hill | Florence | Fort Omaha School | Howard Kennedy | Kellom | Lake | Long | Miller Park | Minne Lusa | Monmouth Park | North Omaha (Izard) | Omaha View | Pershing | Ponca | Saratoga | Sherman | Walnut Hill | Webster

PUBLIC MIDDLE SCHOOLS: McMillan | Technical

PUBLIC HIGH SCHOOLS: North | Technical | Florence

CATHOLIC SCHOOLS: Creighton | Dominican | Holy Angels | Holy Family | Sacred Heart | St. Benedict | St. John | St. Therese

LUTHERAN SCHOOLS: Hope | St. Paul

HIGHER EDUCATION: Omaha University | Creighton University | Presbyterian Theological Seminary | Joslyn Hall | Jacobs Hall | Fort Omaha

MORE: Fort Street Special School for Incorrigible Boys | Nebraska School for the Deaf and Dumb

Listen to the North Omaha History Podcast on “The History of Schools in North Omaha” »

Leave a comment