North Omaha is home to no fewer than a dozen cemeteries. Some are pioneer burial sites with struggles to save them and get Omahans to visit, while others are haloed religious grounds with important ceremonies and meaningful iconography throughout. One is larger than all others though, and is packed with vital city leaders as well as everyday people. This is a history of the Forest Lawn Memorial Park in North Omaha.

Why Forest Lawn?

Omaha has always had a lot of ideas about what growth should look like. For more than 30 years, regular people filled the streets and houses that made the city grow and work. City leaders, including businessmen and politicians, worked to make Omaha a place they wanted to live in that would also attract more people to live there. They laid out the original city, started suburbs, opened schools, paved streets, created churches and hospitals, put in sewers, and did all the important things.

That’s why, when they realized that the little Prospect Hill pioneer cemetery on a big hill looking over downtown Omaha wasn’t big enough for the city’s needs, city leaders worked to start a new burial ground.

In September 1885, a statement went into the Omaha Daily Herald that said, “It has been apparent for some time… that this cemetery was so occupied that another and large place of burial must be sought soon. I apprehend that interments here will cease very soon, and the lot owners who wish to have the grounds maintained, will donate a certain sum of money, the interest of which will suffice to keep the lots and walks in good shape, as has been done under like circumstances in other cities.”

Within that statement are two reasons why Forest Lawn was started. One was size and availability of space at the city’s main cemetery. The other reason became apparent in the last three words of the statement: …in other cities. Given its aspirations to be a big city, Omaha needed a big cemetery and Prospect Hill wasn’t it. There needed to be a new place.

Establishing Forest Lawn

The Nebraska Legislature passed a new law in 1885 allowing large cemeteries statewide, and ensuring these would be not-for-profit organizations. Since it was established in 1885, Forest Lawn has been a mutually owned organization that operates without profit. The title of every plot rests with the lot owners and not with the cemetery itself.

The cemetery came together within a year of the committee being established. A group of eight men formed the Forest Lawn Cemetery Association almost immediately. The founders of the cemetery were:

- Banker Herman Kountze (1833-1906)

- Pharmacist James Forsyth (1838-1913)

- Storeowner William R. Brown (1851-1931)

- Storeowner Milton Rogers (1822-1895)

- Warehouser M.H. Buss

- Storeowner John H. Brackin (1828-1886)

- Railroad official Hugh G. Clark (1855-1914)

- Businessman J.J. Brown (-1901)

- O.S. Woods

- Charles H. Brown

Starting in the 1860s, a storeowner in Florence named John H. Brackin (1828-1886) homesteaded west of Florence. In 1884, he offered to sell 320 acres to a new committee for the Forest Lawn Cemetery for $32,000 at $100 per acre, and he took a seat on the organizing committee. There was a Potter’s Field near the intersection of Young Street and Mormon Bridge Road that already existed on the land, and kitty-corner was the old Cuter’s Park Cemetery, which was forgotten for more than 150 years after it was used. There are two waterways at Forest Lawn called Milk Creek and Spring Creek, and originally, there were also 100 acres of forests. Brackin claimed “15-20 good views of Omaha” with the ability to see “20 miles up and down” the Missouri River valley.

The first burial at the cemetery did not happen until 1886, and was the body of the man who sold the land to the Forest Lawn committee and sat on it, too, John H. Brackin. He died in March 1886 in California, was originally buried at Prospect Hill, and was later moved to Forest Lawn. Technically, Brackin was buried on his own farm.

Throughout the years a number of businesses rose and fall on the fate of the cemetery, too. In addition to the eventual streetcar line that made money from riders, there were several florists located along Forest Lawn Avenue who sold to mourners, including the House of Flowers and the Minne Lusa Florists. In 1914, Omaha monument marker George F. Shepard opened his business on North 40th Street, making grave markers and more for the cemetery.

Designing the Cemetery

Brackin’s farm was covered in corn and wheat, and converting it into a rolling cemetery would take a visionary.

In an under-explored impact on Omaha’s development, popular Cincinnati cemetery designer Joseph Earnshaw (1831-1906) was awarded a contract to landscape the cemetery. Earnshaw surveyed and platted the grounds, and after almost two months in Omaha, he designed maps and land surveys with plans, They included “laying out avenues, lakes, public vaults, chapel, gateways and other features.” In addition to laying out Omaha’s main cemetery, Earnshaw also laid out cemeteries in Cincinnati, Ohio; Terre Haute, Indiana; Saginaw, Michigan; Canandaigua, New York; and Buffalo/Niagara, New York, as well as other cities. Several of these cemeteries are recognized for their historical significance with listings on the National Register of Historic Places today.

Earnshaw had a trademark “lawn plan” in his cemetery designs that used the existing landscape. In Forest Lawn, that meant the property’s rolling hills had groves with trees and shrubs planted throughout. There were also wandering roads, sidewalks and a lake in the original plans.

Original estimates included 1,000 lots and 200 single graves sites, which were intended to be expanded on later. Almost as soon as the cemetery was schemed, the Forest Lawn Avenue was planned to extend from the Main Street in Florence to the cemetery gates, which were originally located at North 40th and Forest Lawn Avenue. Also included in early plans were a railroad spur built by the St. Paul and Omaha Railway Corporation that would extend from their mainline from the original location of the Florence Depot to the cemetery. However, that idea was never brought to fruition.

Gaining and Losing Prospect Hill

Immediately after the Forest Lawn trustees committee was established in 1885, a longtime real estate broker in Omaha named Byron Reed donated the Prospect Hill Cemetery to the new organization. After managing Prospect Hill himself for 20 years, Reed didn’t want to be in the cemetery ownership business any longer. In addition to donating all the land at Prospect Hill to Forest Lawn, he also gave all the money for cemetery upkeep to Forest Lawn, according to the Omaha Daily World on October 25, 1885. In 1887 the Forest Lawn board closed Prospect Hill to burials, and in 1888, the board voted to close Prospect Hill permanently. They expected that every Prospect Hill burial would be moved to Forest Lawn eventually. The Forest Lawn trustees stopped tending Prospect Hill, and soon after the entire cemetery looked terrible and was run into the ground.

Protests from lot owners in Prospect Hill began in 1892. In the mid-1890s, the Prospect Hill Cemetery Association was formalized and after a lengthy battle in court and through the newspapers, in 1898 the association formally gained control of their cemetery. An independent nonprofit association has ran it since then.

Read my article on the history of Prospect Hill »

Magnificent Buildings

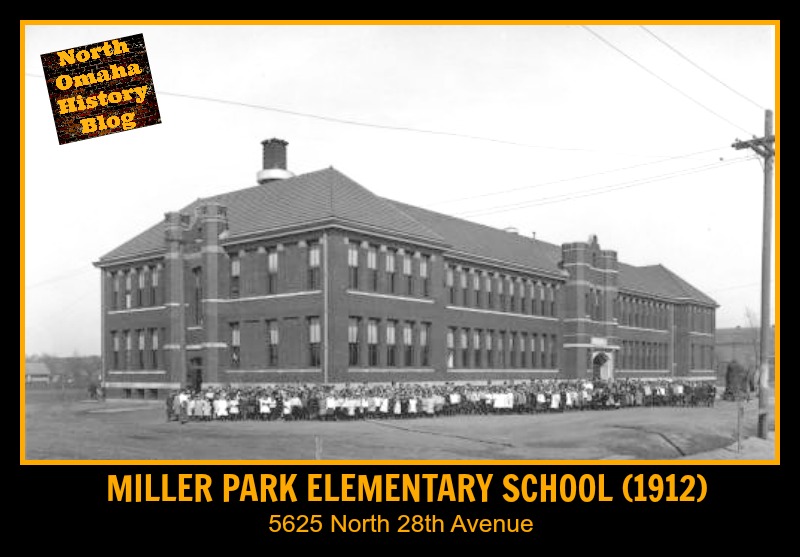

In 1888, the first building in the cemetery was constructed. It was a residence for the sexton or caretaker at the cemetery, and was built for $3,000. The building contained an office for the superintendent of the cemetery, too, and was used for just over 15 years. When the cemetery’s caretaker had a baby at home in 1906, the newspaper made fun by reporting, “The record does not show that the stork encountered any difficulty in winging its way around the marble markers and monuments, and the incident is only cited to show the versatility and up-to-dateness of the grand old bird.” That event happened in the original caretaker’s house, which was located on the northwest corner of North 40th and Forest Lawn Avenue, across the original entry road from the current caretaker’s house.

Another early building constructed at the cemetery was an all-glass greenhouse constructed near the entrance. It was built around 1889. By the 1890s, the cemetery staff worked from an office in the Omaha Bee building downtown.

In 1902, the cemetery completed construction of its first mausoleum vault near the original entrance. Built for $7,000, the vault was 50 feet long, 30 feet wide, and contains 96 catacombs and 600 niches for cremated remains. It was built with brick and lined with slate. The building was constructed underground and only its front side faces outward.

While a lot different elements to the cemetery were built in its first two decades, construction at the cemetery didn’t really take off until after the turn of the 20th century. In 1905, the streetcar company announced they would build a line from North 30th to North 40th Street to take visitors to Forest Lawn. To suit the incoming flood of people who had never been there, the cemetery board responded.

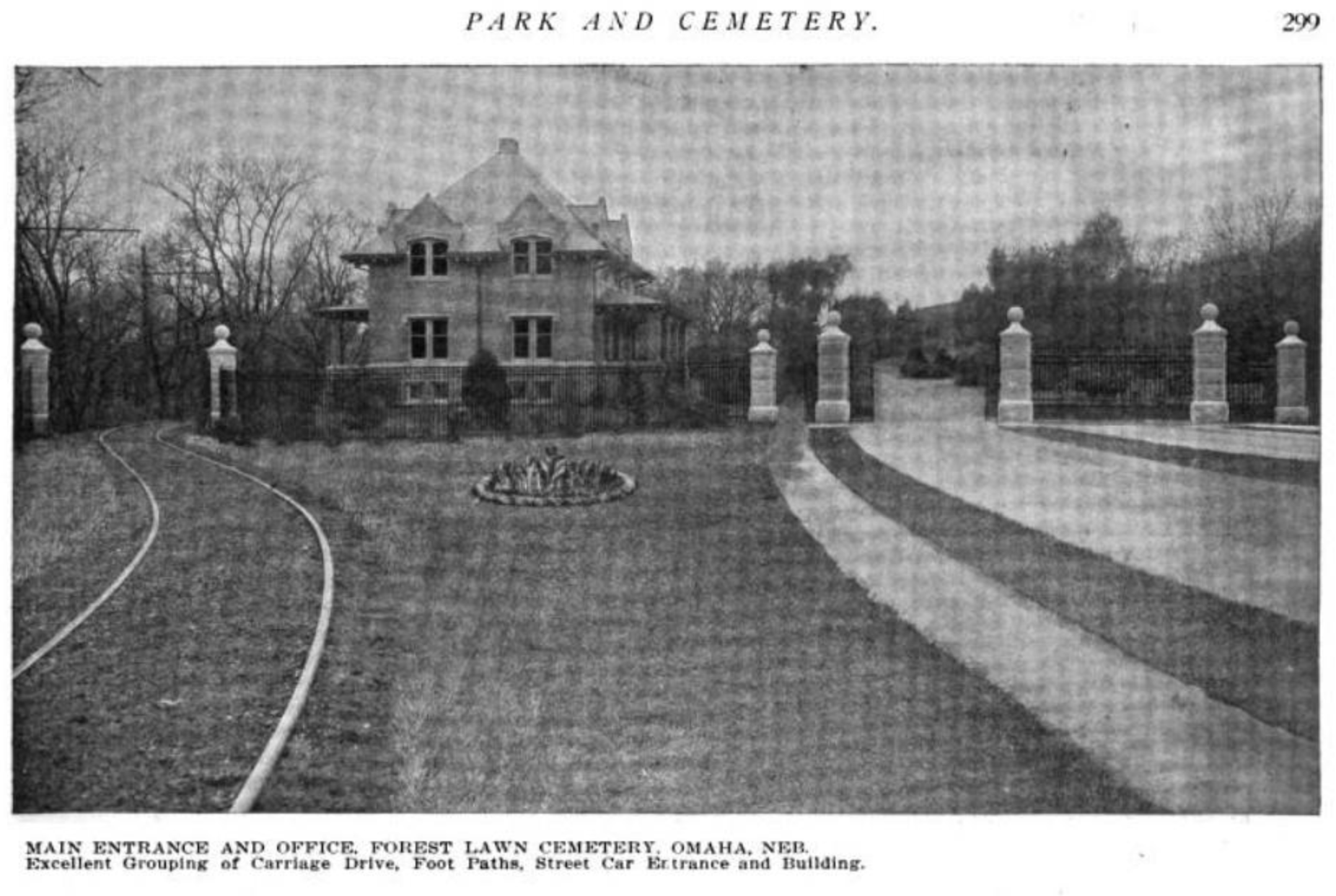

That year, in 1905, they had “an architect prepare plans for an elaborate stone and pressed brick entrance to the cemetery, which will include a magnificent arch, the superintendent a lodge on one side, and an office and record building on the other, all working into one harmonious design.” It was all estimated to cost $18,000, which was the largest single investment in Forest Lawn to that point. While the grand entryway was never constructed, there was another design to replace this soon afterwards.

That plan was announced in February 1906 by popular Omaha architect John McDonald (1861-1956). The Omaha Bee announced McDonald contracted with the cemetery association and completed the plans, which involved a simpler stone and steel gated entry, with nearly identical buildings located across from each other just within the front gates, on the north and south sides of the Forest Lawn Avenue. A builder named John Harte (1854-1924) was contracted to construct the buildings that year, too. The plans called for a streetcar to run through a set of gates into the cemetery, with automobiles being prohibited from coming inside the cemetery.

The Forest Lawn streetcar started running in May 1906, and on Memorial Day the newspaper reported, “the cemetery was crowded with people at an early hour in the forenoon…” The streetcar ran directly into the cemetery so riders could get out within the fence line.

Without explanation, the north building was not constructed. The south one was though, and stood for more than a decade afterward. After that, the cemetery kept building.

In both 1913 and 1915, the beautiful Forest Lawn Chapel was dedicated. Designed by popular Omaha architect John McDonald, the building is 64 x 40 feet and is covered with granite and green tile roofing. The interior is finished in marble and bronze, with art glass windows made of bronze and mother of pearl. There are tableaus inside with four angels. The main room has a dominant inscription covered in gold, and several other areas. The basement of the building was the original crematory for the cemetery, and includes 50 glass-doored niches to hold cremations, and 24 temporary crypts. The site of the first-ever cremation in Nebraska, today the crematory and temporary crypts aren’t used anymore. However, there are 210 additional crypts that are still in use. In 1990, the building was restored to its original grandeur. There is space for seating approximately 60 people in the chapel.

“The structure is one of the most beautiful in the country and stands on a rise of ground facing the main entrance drive, where nature has been assisted by skillful landscape treatment.”

—”Forest Lawn Chapel-Crematory Building Will Be Appropriately Dedicated With Addresses Today,” Omaha World-Herald, May 16, 1915.

Around 1915, a greenhouse was built on the north side of Forest Lawn Avenue just inside the original gates to the cemetery. It took the location of the original caretaker’s home, which was replaced in 1906. Both of the structures were designed in the Jacobethan Revival style, and included a new caretaker’s residence and a greenhouse. The new caretaker’s residence sat opposite of the site of the original caretaker’s residence, across Forest Lawn Avenue from the greenhouse.

Located just within the gates, the caretaker’s house is a 3,000-plus square foot house with at least 10 rooms. Originally designed to replace the 1888 caretaker’s house, it eventually housed offices for the cemetery, then became a general purpose facility. There are reports that the home was occupied by a caretaker of the cemetery through the 1990s. It has been abandoned for at least 15 years though, and currently Forest Lawn is planning to demolish the structure.

Built at the same time, McDonald also designed the greenhouse at Forest Lawn directly across from the caretaker’s house. It sat where the original 1888 caretaker’s residence was located. Growing flowers, evergreens, trees and shrubs, everything in the building was for the cemetery and it’s mourners. An annual chrysanthemum show was held at there with varieties sent from California and New York for the orchid section. Some years there were over 6,000 flowers included in the show, which was held from the 1930s through the 1960s. A May 23, 1925 ad said, “The greenhouses at Forest Lawn cemetery (west of Florence) are filled with beautiful cut flowers and blooming plants. You are invited to see them. Lot owners are requested to call the greenhouse now and select plants to be set out soon for Memorial Day.” In 1953, the greenhouse was severely damaged by a thunderstorm, and by 1965, it was demolished. Today there are no signs it ever existed.

Another notable structure to call out was a bridge across a lagoon located in the south side of the Forest Lawn grounds. Sleuthing by Omaha historian Michele Wyman has found that the bridge was part of a beautiful strolling path around a lagoon, which also had statues, benches and more. Built around 1900, the last known photo of the bridge was in 1960. The lagoon was also gone by then, and today there’s no evidence that either ever existed.

Monuments

In 1899, a fundraiser was started for the the “Children’s Memorial,” a monument to soldiers that Women’s Relief Corps throughout Omaha raised money for from students in schools around the city. The Ladies Union Veteran Monument Association installed a “stately marble shaft” in memory of US Army soldiers from the Civil War in 1905.

The Grand Army of the Republic Monument was dedicated in 1905, and rededicated in 1991. In 2014, it was restored as part of an Eagle Scout project. According to the Omaha World-Herald, “The Grand Army of the Republic was a fraternal organization for Union Army veterans of the Civil War. It was dissolved in 1956, when its last member… died at age 109.”

In 1913, the Knights of Pythias dedicated a new monument at the cemetery “to commemorate the founding of the first lodge” of the organization in the Allegheny Mountains. It was dedicated to the memory of George H. Crager (1837-1908), who established the first lodge in Omaha in 1868.

The Women’s Relief Corps dedicated another monument in 1917. This one was in memory of the departed members of the organization, and was claimed to be the second monument of its kind in the country.

By the 1920s, the cemetery was advertising a non-monument section that would use only flat-to-the-ground markers instead of tall ones. This was advertised as intentionally creating a “park-like” effect for people to enjoy the grounds.

Potter’s Field

In 1887, the Douglas County Commissioners approached the cemetery board to locate a new pauper’s cemetery within Forest Lawn. Finding that the Potter’s Field already existed in the northwest corner of the land along Young Street, this was not a reach of the cemetery’s purpose. The next year the cemetery took a contract with the county to bury transients there.

Read my article on the history of Potter’s Field »

Notable Burials

Several organizations own parts of the cemetery for the burials of their members. As early as 1886, the Masons moved their burial program from Prospect Hill to Forest Lawn. Leading the charge, soon after organizations including the G.A.R. and the Omaha Typographical Union bought into the cemetery. The Typographical Union was the actually the first organization to purchase a lot in the cemetery, and by 1899 it had three printers’ graves. The Masons had room for 800 burials.

Part of Forest Lawn was made into a national soldiers’ cemetery and today, the cemetery is home to the largest number of military graves in the Omaha area. Soldiers from the Civil War, Spanish War, the two World Wars and the wars in Korea and Vietnam are buried at Forest Lawn, along with soldiers from the last 50-plus years.

By 1906, there were almost 10,000 burials at the park, with “only twenty-eight out of 320 acres in the cemetery” that were sold. In the decades before and after, many, many markers, monuments, and other memorials were put in Forest Lawn.

Some of the notable Omahans buried in Forest Lawn over the decades have included the Bostwick, Kountze, Lauritzen, Poppleton, Dietz, Lowe, and Cornish families. Omaha notables including Peter Kiewit (1900-1979), Gottlieb Storz (1852-1939) and Dr. Samuel D. Mercer (1841-1907) are all buried there. Founders of Mutual of Omaha, Clair C. (1879-1952) and Mabel L. Criss (1881-1978) are buried there, as well as George (1848-1916) and Sarah Joslyn (1851-1940).

According to the phenomenal Marta Dawes, there are many important Nebraska politicians buried there including Nebraska Territory Governor Alvin Saunders (1817-1899); US Senator Gilbert Hitchcock (1859-1934); US Senator Charles Manderson (1837-1911); and US Senator Robert Beecher Howell (1864-1933) , among others. Mayor of Omaha and Governor James E. Boyd (1834-1906) joins the first mayor of Omaha, Jesse Lowe (1814-1868), there too.

The grave of Anne Ramsey (1929-1988) is located in Forest Lawn, and she is the only Hollywood actress buried in Omaha.

Howard Baldrige (1894-1985) was the U.S. Secretary of Commerce, and is buried at Forest Lawn. Omaha criminal and political boss Tom Dennison (1858-1934); publisher of the Omaha World-Herald, Henry Doorly (1879-1961), publisher of Omaha World-Herald; World War I pilot and namesake of Offutt Air Force Base Jarvis Offutt (1894-1918); and billionaire Walter Scott Jr. (1931-2021) are all buried there, too.

Forest Lawn has been one of the main cemeteries for African Americans in Omaha since it was established. For decades, most Black burials at the cemetery were informally segregated, which is obvious from their concentration in certain spots. Many notable Black community members are buried there, including local leader Ferdinand L. Barnett (1854-1932), musician “Professor” Josiah “P.J.” Waddle (1849-1939), attorney Joseph Carr (1857-1924), Civil War veteran Anderson Bell (1838-1903), Dr. William W. Peebles, DDS (1883-1958), abolitionist Lewis Washington (1800-1898), civic leader Nathaniel Hunter (1878-1942), Judge Elizabeth Pittman (June 3, 1921-1998), football great Gayle Sayers (1940-2020), and many others. There have also been everyday people buried at Forest Lawn, including Perfect Peace (1896-1951), Ollie Williams (1865-1934), Boston Green (1838-1908), and Dorcas Lewis (1874-1939). Many historic African American figures in Omaha’s history have unmarked graves at the cemetery today.

In 2021, a group of local history activists secured a grave marker in the cemetery for African American writer and Civil Rights activist George Wells Parker (1882-1931), whose grave was unmarked after he was buried.

Uses for the Cemetery

Throughout the decades, Forest Lawn has been popular and nearly forgotten, very used and nearly neglected. In the early 1890s, grave plot owners protested when they thought the cemetery wasn’t being cared for well. When the streetcar got to the cemetery in 1905, crowds started arriving to visit the dead, as well as just to stroll around the grounds. A quiet retreat from busy urban life, people had picnics and dates at Forest Lawn. A 1932 ad showed the cemetery association itself held concerts there, as well as other special events including flower shows and more.

Of course, competition quickly arose and by 1900, the newspaper reported there were 15 cemeteries throughout the city. Luckily, everyone accommodated its own and Forest Lawn kept pace.

If you’re following along, the cemetery started to be referred to as the Forest Lawn Memorial Park by 1940.

Structures at Forest Lawn

Forest Lawn Memorial Park has been constructing buildings since it opened. In 1911, the Omaha Bee declared John McDonald “the architect of the Forest Lawn association.” His contributions to the cemetery included designing the original stone entry, including sidewalks, a road and streetcar access; the second caretaker’s home; the second greenhouse; first chapel and crematory; and a mausoleum. He likely designed the bridge over the lagoon, and several of the stairways and other park features within the cemetery.

However, starting in the 1960s, the leadership of Forest Lawn became focused on erasing the historical buildings from the cemetery. After demolishing the greenhouse, they deleted the bridge over the lagoon. Later, they instituted a strict policy for not installing new grave markers for plots that didn’t have them that is still in effect today, which potentially erases the historical value of many people within the grounds.

- 1887: First caretaker’s house built

- 1890: First greenhouse built

- c. 1900: Bridge

- 1906: Second caretaker’s house built; first moved to new location

- 1915: Second greenhouse house built

- 1902: First mausoleum built

- 1906: Streetcar line constructed removed in c. 1951

- 1911: First mausoleum and crematory started construction, finished in 1913, dedicated in 1915

- 1970: New mausoleum built

- 2014: Forest Lawn Funeral Home built

- 2021: New mausoleum built

According to the Forest Lawn website in 2023, “Our tax status allows us to reinvest in the maintenance of our beautiful grounds and architecture for the benefit of the community we serve.”

Forest Lawn Today

In 2023, Forest Lawn is home to some of the most prominent names in Omaha, and is the most highly regarded burial place in the city. Today there are 349 acres to the memorial park, which is the largest cemetery in Omaha and the second-oldest. It is the largest cemetery between Chicago and San Francisco. One

The Forest Lawn Cemetery Association built a new funeral home in the cemetery in 2014. Seating 300 people, patrons can use either this facility or the historic chapel for funerals. The 20,000-square-foot building has space for preparation of bodies for burial, offices and a reception hall. Today, there are three masoleums at Forest Lawn today, with the most recent one opened in 2021. Unlike the older ones, the new 11,000 square foot building constructed near the cemetery entrance.

The cemetery trustees approved moving the gate from the Florence neighborhood in the 1970s. Relocated facing the Mormon Bridge Road, this signaled a growing disdain for its North Omaha roots. Also in the 1970s, the cemetery started decommissioning its historic buildings. It stopped using the crematory then, as well as the chapel. While the chapel has been restored, its usage has largely been replaced by the newer funeral home located near the new main gate. However, it is now used for weddings and funerals in addition to the occasional funeral.

The Forest Lawn Memorial Park is renowned for its upkeep. As a part of the Nebraska Statewide Arboretum, in 2020 it received a presidential citation for its beauty. There are four Nebraska State Champion Trees within the cemetery.

The Forest Lawn leadership’s apparent disdain for its own historical value beyond its burials. Hellbent on modern construction and building to compete with other area cemeteries, the organization clearly lacks the integrity it needs to support the value and need for its history in the city.

More importantly, while it’s obvious that today while the cemetery is revered by many for its contents, the Forest Lawn Memorial Park is deeply separated from the North Omaha community. From the 1960s to today, the leadership of the institution has apparently and permanently shut off access to the cemetery from North Omaha. By closing the entrance from Forest Lawn Avenue to both cars and pedestrians, the cemetery has smacked the community in the face by isolating its namesake road, which was named for the cemetery by the City of Florence when it was opened. With plans to demolish the caretaker’s house at the eastern edge at the former entrance, the cemetery board and organizational leadership will complete a 60-year objective to isolate, segregate and otherwise disassociate itself from North Omaha.

Without active protest, collaborative planning, deepened investment, and potentially new leadership, the Forest Lawn Memorial Park will continue to stonewall North Omaha and deny its obligation to the community. Further, it will keep demeaning the community by perpetuating negative views of the area, its residents, its climate and its goals.

Hopefully North Omaha’s history will mean something to this place that means so much to so many of us.

Special thanks to Michaela Armetta and Michele Wyman for their research that assisted this article!

You Might Like…

MY ARTICLES ABOUT CEMETERIES IN NORTH OMAHA

Cemeteries: Prospect Hill | Potter’s Field | Forest Lawn | Golden Hill

Other: Grave Robbing | Missing Cemeteries | “The Woman in White”

Elsewhere Online

- History on the official Forest Lawn website

- Forest Lawn on Graveyards of Omaha (my favorite!)

- Forest Lawn Memorial Park on Wikipedia

- “Meeting (and Exceeding) the Needs of Nebraska Families” by Patti Martin Bartsche for American Cemetery & Cremation magazine.

- Forest Lawn Memorial Park on Findagrave.com

BONUS

Leave a comment