Just like today, early Omaha was filled with schemes, plans and big ideas by capitalists who wanted to make a lot of money. While these dreams came true for a few, one of these ideas was located in a place that doesn’t exist anymore, making it easy to see this big idea didn’t work. This is a history of the East Omaha Factory District.

Roots of Industry

East Omaha was originally claimed in 1854, with a final claim on the land in 1856. By the 1880s, the land was in the hands of various owners as well as being under contention. The arguments over ownership were from squatters who claimed it, as well as the States of Nebraska and Iowa, who couldn’t resolve which state the area laid within because of flooding.

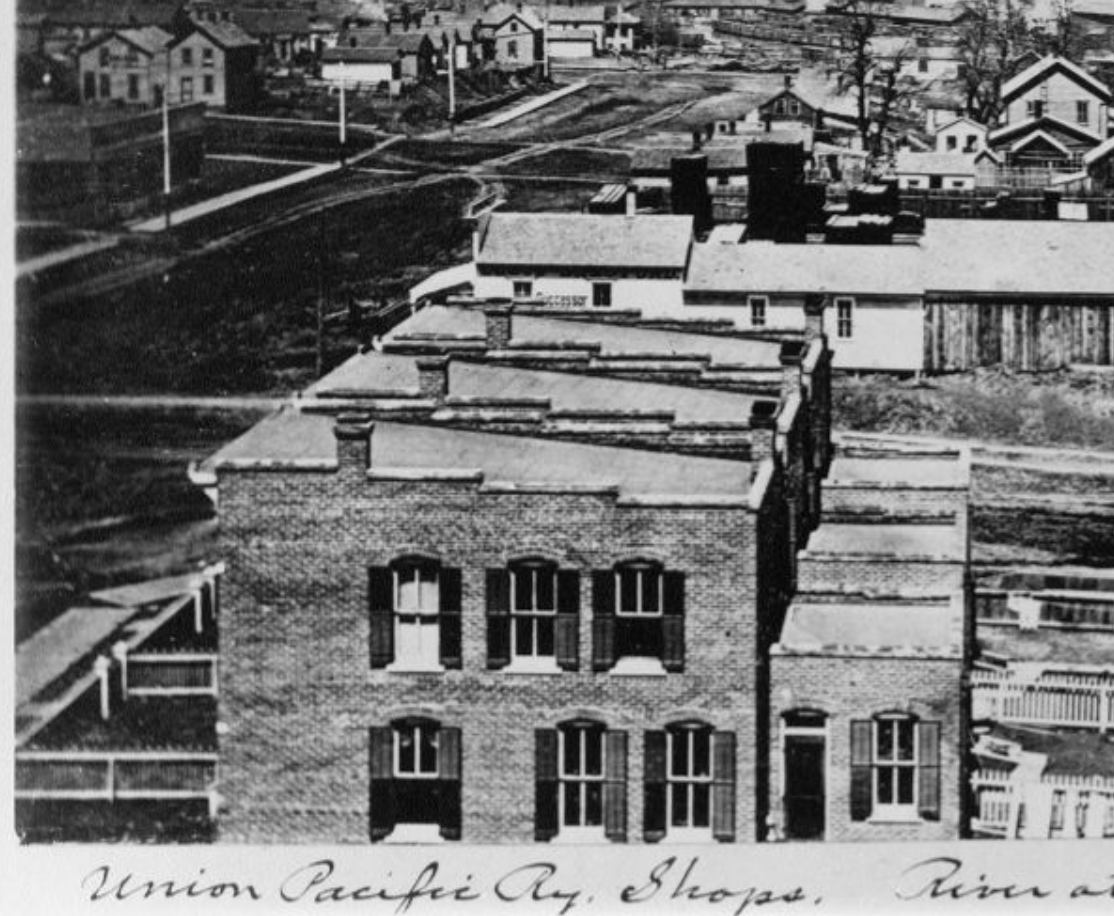

The East Omaha Land Company was established by East Coast investors determined to make a buck in the young state of Nebraska. In 1883, they hired fellow investor Authur S. Potter as their manager, and he singularly convinced his business partners that East Omaha could be to Omaha what South Omaha was; a magic city with massive, fast growth to make them rich. The land company bought most of the land comprising modern-day Carter Lake and the area south of Eppley Airfield today, almost 2,000 acres. Potter was also an investor in the company. Starting immediately, the East Omaha Land Company started grading streets, building an electric streetcar and putting up workers’ homes.

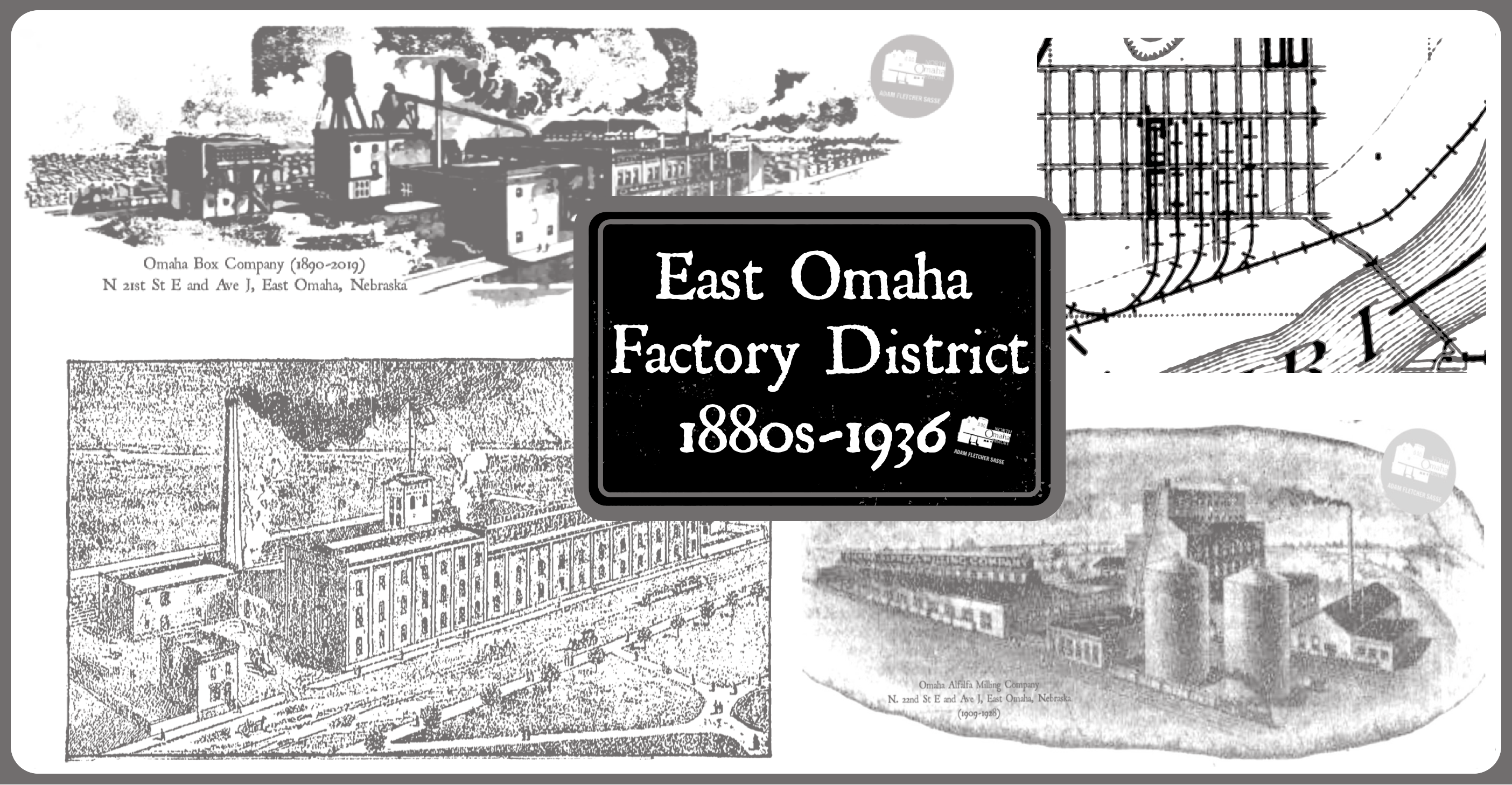

Soon after, he began inviting enterprising businesses to construct large industrial factories to move into the newly-christened East Omaha Factory District. The factory district sat from North 20th Avenue East to North 22nd Avenue East, from Locust Street to Avenue G.

The first group of houses built in East Omaha was constructed in 1890 by the East Omaha Land Company. Intended for workers at the factories, there were originally 24 small homes with city water, sidewalks and fences. In two more years, there were a dozen more along with pop-up homes and other places for people to live. Essentially a company town, this area grew fast.

In 1891, the East Omaha Land Company also setup an electric streetcar running from the intersection of North 16th and Locust Streets to these houses and the factory district. Operated by the Interstate Railway and Bridge Company, it was about 2.5 miles from the factory district. The line started at the intersection of North 16th and Locust and shot east to a terminal at North 27th Street East and Locust Avenue. The streetcar was powered by a huge electric motor (a single reduction Westinghouse with two 20 horse power motors for each car) housed at North 25th Avenue East and Locust Streets. There were two motor cars and two “trail” cars on the line, with one of each heading each direction several times throughout the day. The original intention of this line was to connect Omaha and Council Bluffs via streetcar over the East Omaha Bridge and three years after its founding the company was renamed the Omaha Bridge and Terminal Company.

The East Omaha Bridge was built in 1893 by the same authority that installed the streetcar, and when it opened the bridge was operated by the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad. Within a few years, the terminal company bought railroad tracks on the north side of Carter Lake from the Union Pacific to expand their network, and soon bought others too.

Attracting industries to the area was a success, and between the late 1880s and the late 1890s a number of large plants were built in East Omaha. Attracted by the railroad, streetcar, nearby workers for hire, and free land from the East Omaha Land Company, these plants were first referred to as the East Omaha Factory District by the Evening World Herald in 1891.

Businesses in the District

Throughout the years, some of the businesses located in the factory district included the Barber Asphalt Paving Company, and the Adamant Wall Plaster Company. The Omaha Cereal Company plant was there too, and the Omaha Wagon Works along with the Monitor Hard Plaster Works.

By 1890, the East Omaha Box Company was built there, too, and maintained its factory there through 2018. In 1891 the Marks’ Brothers Saddlery Company built a large plant in the East Omaha Factory District. Manfucturing saddles and harnesses, they employed 75 people in their three-story brick building. In 1893, the Martin and Morrisey factory was located there, which might have been the same as the Martin Steam Feed Cooker Company, which had a plant in the East Omaha Factory District. The American Cereal Company, originally called the Pearl Hominy Company, had a factory there, too. In 1891, 15 workers in their East Omaha mills were making 200 barrels a day with pearl hominy and corn meal. They sold most of their product in the northwest and the South.

During the 1890s, a small town emerged around the factory district grew exponentially. Despite never formally being established, it was referred to as the town of East Omaha and included homes for workers, a park, and several businesses and churches. A school was opened there, and eventually as many 2,500 residents lived in the area.

The J. T. Robinson Notion Company built a four-story plant in East Omaha in 1885, eventually buying the neighboring DeGraff Manufacturing Company, which had a four-story building in the East Omaha Factory District. 125 workers at this plant made overalls, work shirts, jumpers and pantaloons, and six traveling salesmen sold them across the country. Kilpatrick-Koch Dry Goods Company bought them out by 1892, and kept operating the large factory. Kilpatrick-Koch closed during a financial crisis in the mid-1890s.

The Omaha Cereal Company opened in the late 1880s, burned down twice and closed permanently in 1916, similar to the Omaha Hay Company, which was located next to the box factory. Their factory was permanently closed after a massive fire in 1901. It didn’t close because of that single fire though–but because of the three others in the decade before that! The Omaha Alfalfa Milling Company suffered a similar fate. There were a lot of fires in the factory district.

In 1886, Levi Carter opened the Carter White Lead Company south of downtown Omaha. A generous offer of land and tax breaks lured him away from the old site of the Omaha White Lead Company by the railroad depots, and he built large. In 1885, prices bottomed out in the lead market and the company was forced to shut down the works. The next year, Carter bought it cheap and reopened the plant, speculating the market would come back. It did, and within five years he was stinking rich. The Carter White Lead Company was born. Levi Carter ended up selling paints and all kinds of treatments for homes to hardware stores and paint stores across the Northeastern United States. He bought a formula for white lead paint concocted by a Dutch entrepreneur in the 1880s. Within the next 40 years, Carter brand paints were sold across the entire nation. That brand stopped being used when the Dutch Boy brand was used exclusively. On June 14, 1891, the Carter White Lead Company caught fire and burnt to the ground. It incinerated the entire plant, which had just been rebuilt to increase production. The only things saved were the warehouse and office, and several outbuildings. The plant itself was completely obliterated. Carter moved the plant to East Omaha and rebuilt on an even grander scale.

By the end of 1891, a new plant that cost $200,000 was built in East Omaha, and within two years the plant’s output reached 7000 tons. There were 21 buildings at the new plant, which was located at North 21st Street East and North 22nd Street East, between East Locust Street and Avenue J. Carter’s company became the biggest white lead refiner in the nation, and owned the Omaha factory and another in Chicago.

A U.S. Supreme Court affected the factory district’s development in 1892. After a court battle by the States of Nebraska and Iowa, they agreed to re-plat the area. The dividing line cut the factory district in half, taking the region that is southwest of Locust Street and Abbott Drive into Iowa. While they left the nearby Courtland Beach amusement park in Iowa, the financial power of the factory district was given to Nebraska.

Flooding in 1897 dampened enthusiasm for the factory district as businesses realized the pikes created for the railroad coming from the bridge weren’t enough to stop the Mighty Missouri River from flooding their properties. Along with a financial crisis the year before, thousands of dollars of flooding damage that year dissuaded further investment in the properties quickly. Two years later, more flooding further suppressed interest despite the East Omaha Land Company making a big show of taking newspaper reporters around their 32-miles of railroad tracks to show how no water submerged them at any point.

In 1899, the Wash-A-Loan Soap Company reorganized and left the factory district. Reporting on this, the Omaha World-Herald said, “This company has been a considerable factor in Omaha’s manufacturing world for two years.”

It was 1900 when Edward J. Cornish (1861-1938), commissioner of the Omaha Parks Board, proposed a radical idea to the City of Omaha. He wanted the City to buy all of the remaining undeveloped holdings of the East Omaha Land Company, along with land belonging to Count John A. Creighton, to create a massive park around the lake, which was having a challenging time developing because of the constant flooding. His idea was ultimately limited to only the Nebraska side of the lake, but resulted in the development of the park, named in honor of an East Omaha business pioneer named Levi Carter (1830-1903).

Carter consolidated manufacturing with his new plant in suburban Chicago and closed his East Omaha plant, then died in 1903. Two years later, Edward J. Cornish was elected president of the company’s board and appointed president of the company. He reopened the plant, and sold the company in 1907 to National Lead, the white lead trust. They closed the plant in 1916, and continued making the Dutch Boy paints and paints under the Carter name, too.

In 1900, the East Omaha Land Company took a couple to court in Nebraska to force quit a home sale. However, because of the land dispute settled by the US Supreme Court almost a decade earlier, the court ruled the company had to go to Iowa. When in court there, a judge decided that since the company had been established in Nebraska and never registered in Iowa, it had to authority to enforce deeds to its land in Iowa. That led to financial destitution, and without a way to rectify the situation the business dried up. By 1901 the East Omaha Land Company was done and went into receivership. Despite a demand from competitors that the streetcar tracks ultimately belonging to the company be removed, a judge prevented that from happening. however, this was a clear assurance that that East Omaha Land Company was through.

The bridge was stranded by the river in 1901, rebuilt and reopened in 1904, and rebuilt again in 1908. During that process it was doubled in size and became the largest double-swing bridge in the world for a while. In 1905, the newspaper predicted the rebuilding of the bridge would result in new investment in the East Omaha Factory District, and said that if it worked the city “would have cause for jubilation.”

For the first time in its recorded history, the City of Omaha and the State of Nebraska became concerned about flooding in the district around 1904. Assessing the area’s flood prone nature, they determined a levee system would be necessary but didn’t commit any resources to building them.

The East Omaha streetcar stopped operating by 1903. In 1908, a fire completely destroyed the Omaha Wagon Works, causing more than $100,000 in damage. In addition, the fire also destroyed the Omaha Saddle Tree Company and 14 box cars from the Illinois Central Railroad.

In 1910, the Western Chemical Reduction Company at North 25th Avenue East and Locust Street burned down. The building was repurposed after being built as the streetcar electricity plant in 1892. Explosions marked the fire, with several happening because of poor storage methods at the factory. Two fire hydrants near the plant were clogged up and stopped firefighters from effectively fighting the flames. A man was killed, and the $100,000 plant was a complete loss.

While hard times had descended on the East Omaha Factory District, its growth wasn’t over yet. The Omaha Alfalfa Milling Company opened in 1909 in a vacant building east of the Omaha Box Company factory. Adding onto the existing structure, they built a single-story brick building and added a 20×30′ steel tank for molasses storage. After closing down in 1926, in 1928 the factory was started up again as part of the Honey Dew Mills out of Chicago. However, the Great Depression hit that company hard and the Omaha Alfalfa Milling Company declared bankruptcy and sold all of its property and equipment in 1933.

The Carter White Lead Company dissolved in 1936. All of its property was distributed to the National Lead Company, which was headquartered in New Jersey. The new owner continued to operate the Chicago plant as the Carter Brand of the National Lead Company.

While that was nearly the end of the East Omaha Factory District, it wasn’t the end of industries in East Omaha. Other factories came and went afterwards with smaller operations than during the heydays in the 1890s through the 1920s. Chemical labs, oil companies and other manufacturing came and went. There are still a few light industrial businesses located within the former Town of East Omaha.

Today, there are two obvious remnants of the East Omaha Factory District. The first is the former Omaha Box Company factory, originally constructed in 1890. It was renovated in 2022 and looks stellar today. The other vestige of the old hopes of the East Omaha Land Company is the old East Omaha Bridge, constructed in 1893 and still standing. It was closed permanently in 1980, and today its severely dilapidated and seems destined to fall.

The City of Omaha owns any land that was once designated as part of the East Omaha Land Company division.

Maybe in the future there will be a historical plaque or some other commemoration of the East Omaha Factory District or the Town of East Omaha. Until then, the history lives on in the memories of the older people and in articles like this.

You Might Like…

MY ARTICLES ABOUT THE HISTORY OF EAST OMAHA

SEE ALSO: East Omaha History Tour

AREAS: Town of East Omaha | Carter Lake | Winspear Triangle | North Omaha Bottoms | Sherman | Sulphur Springs | Edgewood Park | Bungalow City | Squatter’s Row | Lakewood Gardens | East Omaha Factory District

BUSINESSES: East Omaha Truck Farms | Spanggaard Dairy | Carter White Lead Company | Nite Hawkes Cafe | Railroads

CARTER LAKE, IOWA: Courtland Beach | Omaha Rod and Gun Club | Carter Lake Club | Sand Point Beach and Lakeview Amusement Park | Omaha Auto Speedway | Lakeside Raceway |

CARTER LAKE PARK: Municipal Beach | Bungalow City | Pleasure Pier and Kiddieland | CCC Camp

PEOPLE: Selina Carter Cornish | Levi Carter | Granny Weatherford

TRANSPORTATION: Ames Avenue Bridge | Eppley Airfield | 16th and Locust Streets | JJ Pershing Drive | North 16th Street | Paine Airfield | Locust Street Viaduct

SCHOOLS: Beechwood School | Pershing School | Sherman School | St. Therese Catholic School

OTHER: The Burning Lady | St. Therese Catholic Church | 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition

Listen to our podcast “A History of East Omaha” online now!

BONUS

Leave a Reply