Many people live unremarkable lives filled with sameness and consistency, while some break the mold. Given the racist nature of Omaha, in the city’s early Black community, there are not a lot of noted Black people. This is the story of one of the first remarkable Black men in Omaha, Richard Dean “Dick” Curry (1831-1883).

Early Years in Omaha

Dick Curry arrived in Omaha right after the Civil War ended in 1865 and was married to Anna. He was born in 1831 in North Carolina. While little is known about his early life, we do know he served as a private in the United States Army during the Civil War. His wife Anna or Annie was born in 1840 in Indiana.

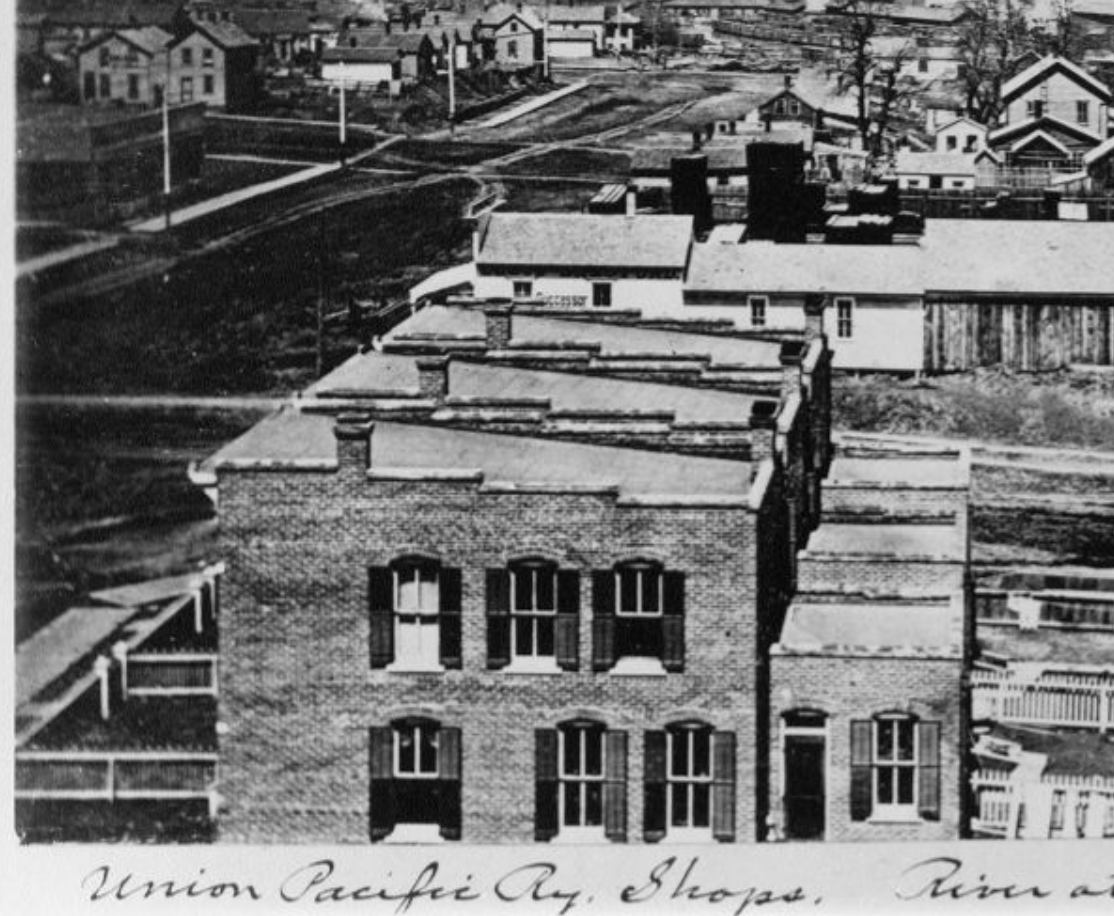

Curry made an impact on Omaha almost immediately. One of the earliest Black business owners in Omaha, Curry started a bar in the Black neighborhood at 13th and Douglas starting in the 1860s. A late newspaper account described him as “a great, broad shouldered and rotund n—- who, in active life, was one of the leaders of his race in this city. He was quite shrewd in business…”

His earliest business in Omaha was called the Occidental Shaving Saloon and Excelsior Bath Rooms and it was located at 213 Douglas Street.

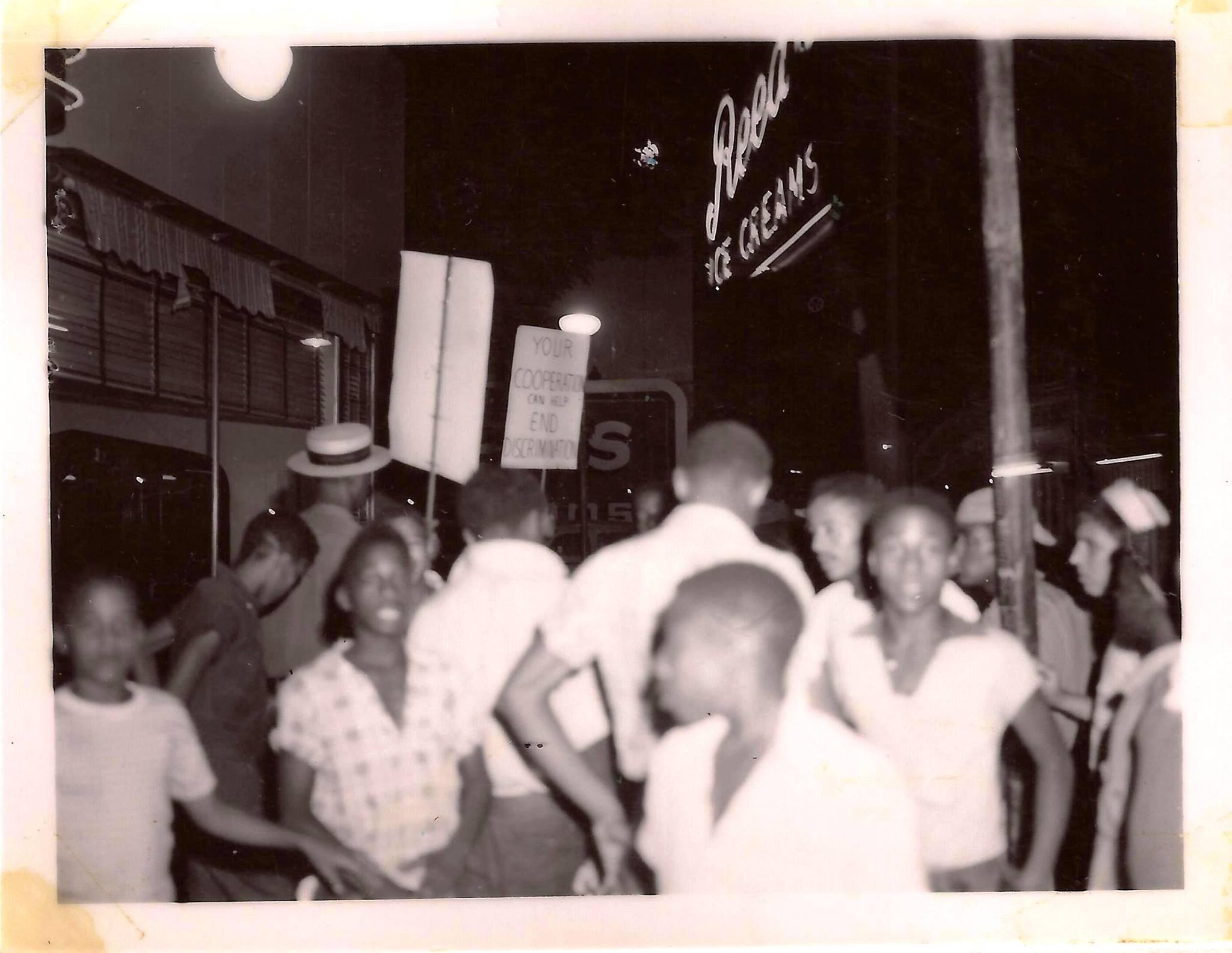

In 1868 he was elected the president of Omaha’s first Black political activism organization, the Negro Republican Club. That same year in 1868, he became the first Grand Master of Omaha’s first Black Masons lodge, called W.D. Mathews #8 under the King Solomon Grand Lodge of Kansas.

In June 1870, Curry was nominated in the Third Ward as the Republican candidate for Trustee or Alderman. However, when white Republicans opposed Curry’s selection and nominated someone else, Black Republicans in the city started expressing real distrust of the party system in general and Republicans specifically.

Curry kept going though. Regularly mentioned along with other leaders like Edwin Overall, John Lewis and Dr. W.H.C. Stephenson, and oftentimes stood alone in the media as the sole leader in the Black community. His involvement ranged across several Black organizations, including clubs for presidential campaigns, Curry was also a member of St. John’s AME Church.

Curry’s business hummed along until the early 1870s when the larger community apparently started turning against his leadership. The Omaha Bee wrote a column about Curry’s saloon, saying “A very respectable colored man said this morning that some of his people were talking of getting up a movement to have the den closed, and not allow it to any longer disgrace the city as well as themselves.” The same article said “…there is no doubt that it has long been a disorderly place, and the headquarters of a bad gang, and the vile whiskey which is dealt out there had brought ruin and disgrace to many a colored man who otherwise would have been an ornament to colored society.” However, the article didn’t name its source and of course, Rosewater was known to dislike Curry.

Along with owning the saloon, in the 1870s Curry owned a barbershop with a gambling room above it on 10th Street. In an interesting turn, in 1874 The Omaha Bee reported, “Mr. R.D. Curry, the fashionable Douglas Street barber, left for the East this afternoon to engage a new force of barbers for his elegant tonsorial parlors.” That didn’t hint at the trouble that was coming.

In July 1874, there was an announcement from White and Duvall that, “We have this day [July 25, 1874] bought out the old and well known establishment of Dick Curry on Douglas Street and will continue to run a first-class barber shop. All old patrons of the shop, as well as new, will be accomodated with a clean shave or hair cut in the highest style of this art.”

In June 1876, Dick’s nephew Henry Clay Curry became the first-ever African American to graduate from Omaha High School. That year, he was one of eleven graduates who went to school along with more than 50 dropouts.

Throughout his early life in Omaha, Curry invested in several real estate properties and accumulated holdings around the city.

Framed, Sent Up & Pardoned

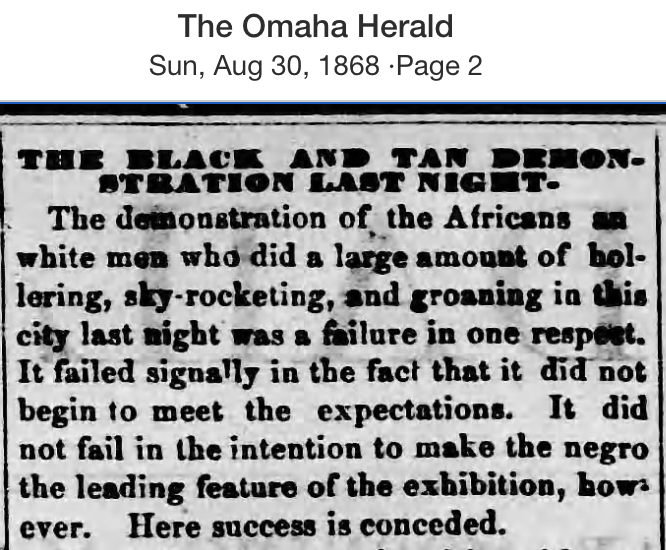

Along with Smith Coffey, in March 1876 Curry was indicted for attempting to murder Edward Rosewater (1841-1906). Rosewater, the editor of The Omaha Bee newspaper, had written several slanderous attacks on Curry and his businesses. When he was arrested, the Bee reportedly there were calls for lynch law to be administered, but I couldn’t find corroboration for that in any other paper.

But the newspaper had received a letter to the editor supposedly written by Curry shortly before he attacked Rosewater in downtown Omaha. However, Curry wasn’t a letter writer and later the card was shown to be fake. He was convicted mostly on the testimony of a single man who testified he was present and heard Curry repeatedly say, “I’ll kill you” while attacking Rosewater.

Curry was sentenced to four years in the Nebraska State Penitentiary in December 1876. Smith Coffey was also indicted. Curry’s sentencing made national news as papers in Memphis, Pittsburgh, Indianapolis and beyond picked up the story.

After serving seven months, in July 1877 Curry was pardoned by the governor of Nebraska after the judge and district attorney in the case, along with several notable politicians in the state called for his release. Apparently, that single witness was subsequently arrested and indicted for robbery, and without his testimony there was no case. The governor found “no person in Omaha who examined the facts, or was familiar with the circumstances, believed Curry ever intended to murder the man who he assaulted.”

In 1878, he was noted as living near North 16th and Chicago, with his saloon at 532 10th Street.

In 1882, Rosewater wrote extensively in his newspaper about the incident claiming that the Omaha postmaster and one of his assistants set up Curry to jump him, but had not been held accountable for their crimes. Rosewater sent Curry to prison while knowing he was not ultimately responsible for the crime.

Dick Curry lived quietly for his remaining years and died at home in November 1883 at 54 years old. His funeral was one of the most prominent in the history of Omaha’s Black community and was held with full Masonic rites at Prospect Hill Cemetery.

Life After Death

According to the 1884 Omaha Directory, The year after he died, there was a “Mrs. Richard Curry” living on “Belleview Road and Haskells Park.” In 1888, a court case regarding Curry’s estate drew the attention of the Omaha World-Herald, which wrote several articles on it. Curry’s brother, Jonathan Curry, his sister Susannah Wilkeson, and a cousin named Henderson Curry were upset over his wife, Anna, and her administration of the estate. According to newspaper reports, he had spent $7,000 in four years and didn’t account for any relatives when Richard Curry died. Mrs. Curry might have shown up on several real estate transactions after the court case, but there was never a conclusion to the event printed in the papers.

Then, in 1890, there was a trial of the postmaster in which the crime of Curry was retried on the premise that the postmaster was actually responsible. Several other men were implicated in the trial, including US Senator Gilbert Hitchcook (1859-1931), with accusations of corruption and political machinations hard at work. During the trial an editor from the Omaha Republican newspaper said, “Curry was a valuable man in a political way at these times. When we wanted him we usually went after him.”

As of 2024, there are no known commemorations or memorials in Omaha for Richard D. Curry, one of the city’s first prominent businessmen, politicians and community leaders.

You Might Like…

BONUS

Leave a Reply