Over more than a 50-year period, one lawyer’s name stands out in the African American history of Omaha. He defended his community constantly, unrelentingly and powerfully as a journalist and advocate who commanded troops during the Great War. Continuously earning the begrudging respect of his white legal colleagues in Omaha, he was also a founding member of several Black empowerment organizations, and involved in many of the city’s important events. This is a biography of Harrison J. Pinkett (1882-1960), Nebraska’s first university-trained African American lawyer.

Before Omaha

Harrison J. Pinkett was born in 1882 in Virginia. One of 15 children, his parents were an African American Civil War veteran and a white woman. His father was a wagon maker, and his older brother Archibald was a lawyer in Washington, D.C.

After attending Columbia University in New York City, Pinkett graduated from Howard University with an Bachelor of Laws degree in 1906. While he attended Howard, Pinkett was a member of the Blackstone Club, secretary of the Bethel Literary and Historical Society, and a member of the Richards Debating Club.

Unable to work in his field though, he found work as a bricklayer and printer in Washington, D.C., where he was the secretary of the first meeting of the Niagara Society in 1905. In 1907, he was admitted to the Washington, D.C. bar as a lawyer. Afterwards he was an apprentice journalist in Chicago.

Moving to North O

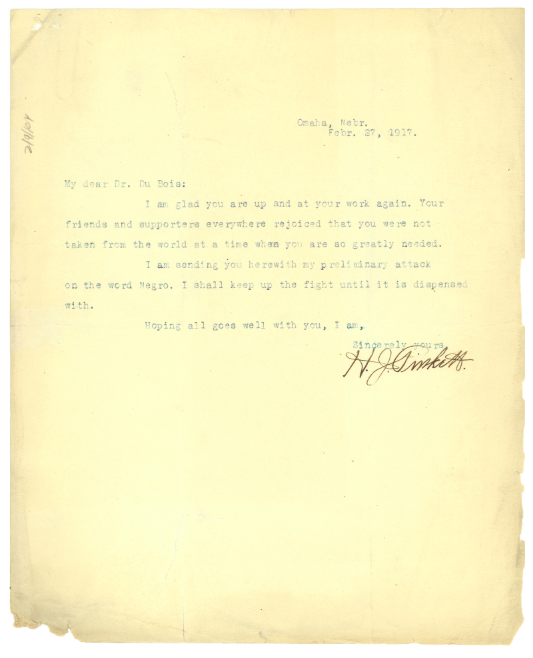

In 1907, Pinkett became the manager and attorney for the Press Bureau and started writing prolifically for Black papers across the country under the pen name “P.S. Twister.” However, when he kept writing critically about national Black leaders like Booker T. Washington and their commitment to capitalism, by the end of 1907, he was asked by Black leaders to move to Omaha to spark more action in the Civil Rights movement here. Pinkett came to the city in 1908, where he became the first university-trained lawyer in Nebraska. Pinkett’s colleague W. E. B. Du Bois visited him in Omaha in the summer of 1908.

He was first married to Eva Madah Pinkett (1879-1948).

Pinkett set up his law practice in Omaha as soon as he arrived, and during his first decade in the city, Pinkett was one of four Black lawyers in Omaha. The others were Silas Robbins, F. L. Smith and J. W. Carr. In 1906, he represented a group of African American US Army soldiers at Fort Omaha in the nationally reputed Brownsville Affair. Pinkett also protested in the media about Omaha’s notorious 1909 Greek Town riot.

Pinkett was frequently involved in litigation and protestations against Omaha’s crime boss Tom Dennison. All through the 1910s, he rallied against Dennison’s crooked vote rigging efforts; in society, he called on Nebraska to become a dry state, fighting against Dennison’s profits from running saloons around the city. Pinkett fought against several taverns in the Burnt District, writing articles in Rev. John Albert Williams The Monitor newspaper against drug sales, bootlegging and prostitution, all of which were Dennison’s racket.

Pinkett is credited with going to the Omaha Presbytery in 1916 to encourage them to start a mission for African Americans in North Omaha. By 1918, the old Hillside Congregational Church at 30th and Lake sold their building, and it became the Hillside Presbyterian Church, also known as the Omaha Negro Presbyterian Church. It stayed open for 40 years afterwards before merging to form the Calvin Memorial Presbyterian Church.

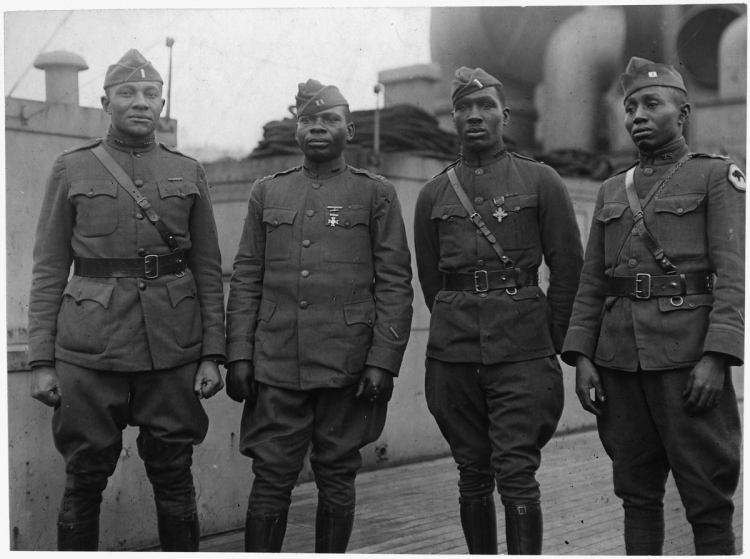

In 1917, Pinkett joined the American war effort during World War I and becoming one of five officers from Omaha to serve. Commissioned at Fort Des Moines as a first Lieutenant, he served as a Buffalo Soldier in the US Army in the 92nd Infantry Division, 366th Infantry in France for just under a year before the war ended. Remembering the day the Armistice was signed, Pinkett was quoted by the newspaper as saying,

“The colored boys under me laid down their rifles, and the Germans did the same. They rushed across the clearing that separated them and embraced with joy.”

–“H.J. Pinkett, Attorney Here 39 Years, Recalls First Armistice in France,” Omaha World-Herald, November 11, 1946

Pinkett kept writing editorial letters to the Omaha World-Herald throughout World War I. Discharged as an Army captain at Camp Upton in New York, he returned to Omaha in April 1919.

Between the Wars

During the year of his return from WWI, Omaha became embroiled by race-baiting and white hysteria. Part of a larger scandal facilitated by crime boss Dennison, several white women and girls blindly accused African American men of attacking them at random across the city. Different white women in different parts of the city at different times all year long. In August, Pinkett sent a letter to the editor saying he’d tracked 20 accusations in the Omaha Bee, and accused them of race-baiting. This came to a head in September 1919, when a disabled African American worker named Will Brown was arrested for such an accusation and jailed. On behalf of the Omaha chapter of the NAACP, Pinkett went to the jail as Brown’s attorney to get his statement. Clearly identifying that Brown suffered from advanced rheumatoid arthritis which crippled his hands and left him constantly hunched over in pain, Pinkett believed there was no way Brown had attacked the white woman. However, regardless of a report in the Omaha World-Herald and other promotion of his observations, Brown was kidnapped from the jail, tied up and beaten, castrated, stabbed, lynched, disemboweled, dragged through the streets by a car, and burned on a bonfire by a mob of 20,000 spectators in downtown Omaha. During the trials afterwards, nobody was ever convicted of a crime in association with the lynching. Pinkett pointed the finger at the Omaha Bee for it’s yellow journalism that enflamed the mob, and long promoted the knowledge that Tom Dennison was behind the entire event, but that wasn’t popularly accepted as fact until the 1990s.

In 1921, Pinkett started The New Era, a short-lived Black newspaper in Omaha. Earlier, a young African American radical named George Wells Parker came to local prominence while writing an article for Rev. John Albert Williams’ newspaper The Monitor. Pinkett hired to Parker be the editor of The New Era, but just a few issues in, Pinkett and Parker got into a disagreement over the content of the paper. Parker left Pinkett’s paper to start his own called The Omaha Whip.

In his paper, Parker accused Pinkett of selling the Black vote to a candidate for Omaha Police commissioner. Pinkett was also accused of helping the Ku-Klux-Klan by Parker. Rev. Williams came out for Parker in this argument, preaching that Pinkett was a member of a citywide conspiracy supporting the KKK. Apparently, nothing came of these allegations, because attorney Pinkett kept working on behalf of the Omaha chapter of the NAACP, which Rev. Williams had founded several years before and worked with continuously until his death.

Pinkett’s advocacy against corruption and crime continued throughout his career. When Robert H. Johnson was arrested by the Omaha Police Department in 1922, Pinkett represented him as a victim of police abuse. Johnson was a supported of an unpopular candidate for Omaha Police commissioner, and Pinkett claimed in court that police arrested him in retaliation. In 1927, Pinkett was attacked by a man with a gun for fighting against gambling alongside Rev. John Pegg Grant at St. John’s AME Church, where Pinkett was a lifelong member.

In 1928, Pinkett created the Omaha Colored Commercial Club with Rev. Williams, Dr. John Andrew Singleton and Thomas Mahammitt. He was also the founder of North Omaha’s American Legion Roosevelt Post 30. He ran for Omaha City commissioner in 1933 and 1936, loosing the primary competition both times.

There have been some gains in the matter of employment in the city government and the county government, but none in the school system, very little in the Utilities District which manages gas, water and ice plants, and there have been no appointments of Negroes in any of the permanent places in the new governmental agencies of Omaha… The white political leaders of the present era in Omaha are not liberal toward the Negro in these respect… The remedy for this condition will be found when the Negroes themselves organize fully and exert their influence for racial betterment… Omaha Negroes have many men and women who possess the capacity and ability and courage and freedom requisite for such a leadership and such a task… They have made progress; their education has been enhanced in all ways; their economic condition has been improved; they have become politically free and will ere long be well and capably led; they have met their general and special problems with courage and patience; and they seek now the opportunity to lay their wonderful fruits and gifts upon the common community altar and to receive from their community those rewards which are the rightful due of all.

—Harrison Pinkett, 1937 as quoted by Jack Angus

In 1945, Pinkett offered a “patriotic address” to the Nebraska State Legislature to commemorate President’s Day.

In the late 1940s, Pinkett was involved in breaking a suspected graft operation inside the Omaha Police Department. After several businesses on North 24th Street were raided, Pinkett protested on their behalf that the raids happened because the owners were unwilling to pay $100 a week for protection money. The clubs included the Business Men’s Club at 2310 North 24th; the Royal Dukes Club at 2737 Parker, and; the Veterans Recreation Club at 1906 North 24th Street. Dozens of people were arrested in those raids on an array of charges. While Pinkett represented North Omaha impresario Jim Bell during this case, he accused every law enforced by the Omaha Police Department since 1919 to be invalid. The judge in the trial eventually dismissed all charges against Bell without further questioning Omaha’s legal basis for arrests.

The Passing of an Icon

Harrison Pinkett’s wife Eva died in 1948. Pinkett’s second wife was Venus Pinkett.

By the time he died, Pinkett was a legend in the Omaha community. Living in the Near North Side neighborhood all his life, he died at home at 2118 North 25th Street on July 19, 1960.

Through the end of his life, he kept writing editorial letters and working as a defense attorney on behalf of Civil Rights. He was the counsel for the Omaha NAACP chapter until he died. Throughout his career with the NAACP, Pinkett won 25 of 26 Supreme Court cases, “all of them focusing on the civil liberties of the American Negro.”

Today, there are no monuments or historical plaques in Omaha in tribute to Harrison Pinkett, and no streets in the city, schools or libraries have been renamed in his honor. Pinkett’s lifelong home is still standing today, but is not recognized for its historical significance as an official City of Omaha Landmark, nor is it listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

MY ARTICLES ABOUT CIVIL RIGHTS IN OMAHA

General: History of Racism | Timeline of Racism

Events: Juneteenth | Malcolm X Day | Congress of White and Colored Americans | George Smith Lynching | Will Brown Lynching | North Omaha Riots | Vivian Strong Murder | Jack Johnson Riot

Issues: African American Firsts in Omaha | Police Brutality | North Omaha African American Legislators | North Omaha Community Leaders | Segregated Schools | Segregated Hospitals | Segregated Hotels | Segregated Sports | Segregated Businesses | Segregated Churches | Redlining | African American Police | African American Firefighters | Lead Poisoning

People: Rev. Dr. John Albert Williams | Edwin Overall | Harrison J. Pinkett | Vic Walker | Joseph Carr | Rev. Russel Taylor | Dr. Craig Morris | Mildred Brown | Dr. John Singleton | Ernie Chambers | Malcolm X

Organizations: Omaha Colored Commercial Club | Omaha NAACP | Omaha Urban League | 4CL (Citizens Coordinating Committee for Civil Rights) | DePorres Club | Omaha Black Panthers | City Interracial Committee | Providence Hospital | American Legion | Elks Club | Prince Hall Masons | BANTU

Related: Black History | African American Firsts | A Time for Burning | Omaha KKK | Committee of 5,000

You Might Like…

- History of North Omaha’s American Legion Post #30

- History of Community Leaders in North Omaha

- History of African American Politics in North Omaha

- Tour of the Civil Rights Movement in Omaha

- African American firsts in Omaha

Elsewhere Online

- “Harrison J. Pinkett” on Wikipedia

- “Harrison J. Pinkett to Jane Addams,” a 1908 letter from the Jane Addams Digital Archive

- “Interview with Mr. H. J. Pinkett” by Fred D. Dixon for the WPA Federal Writers’ Project in 1938.

- Letter from H. J. Pinkett to Editor of The Crisis, April 30, 1929 Enclosing a brief article for their consideration on band leader Dan Desdunes.

BONUS PICS!

Leave a comment