In the last decade, the lynching of Will Brown has received a lot of attention in Omaha and beyond. However, many of the facts in the story have been lost to time and others muddled away. Since volunteering to write more than 300 articles on Wikipedia related to Omaha history starting in 2007, I have searched for little-known details about Brown’s lynching. Here is what I’ve found.

Leading Up to the Lynching

Almost 40 race riots happened across the United States during the Red Summer of 1919. It was called the Red Summer for the blood that filled American streets. Omaha thought it was immune from this race hatred, but late September proved the city hatefully wrong.

Before that and throughout the summer of 1919, Omaha police had taken dozens of reports of violence by African American men against white women, but when they followed them up they consistently found they were hoaxes. In May 1919, W.E.B. DuBois spoke at the Omaha Auditorium, while during that same summer, William Monroe Trotter, editor of the militant pro-Black Boston Guardian, spoke at Zion Baptist Church. Both of these powerful African American speakers might have precipitated the conditions leading to the riots.

Nationally, media hyped up reports of Blacks who rioted against white neighborhoods. After white people armed themselves and waited for mobs that never came, they started forming their own vigilante mobs that lynched, murdered, burnt out and otherwise terrorized Black communities across the country. Sometimes, the yellow journalists who created the media hype would later take back their statements, occasionally offering a “whoops” in the back pages of their papers. Mostly, they didn’t though.

Some white people in Omaha were apparently foaming at the mouth for the blood of African Americans. As early as January 1919, reports were coming into the Omaha Police Department that African American men were accosting white women randomly on the streets of the city. For instance, an Army soldier named Henry Culpepper was arrested for assaulting a white woman. Fresh home from the military in his uniform, he was swept up in a wide net cast by police that brought in 30 other Black men, too. Culpepper was found innocent by the police though, and released. These incidents went on throughout the summer repeatedly, with more than 100 African American men brought to the police station under the pretense of several assaults of white women.

Then, on September 1, 1919, the Omaha Police Department shot dead Eugene Scott, an African American bellboy at Hotel Plaza downtown. Supposedly, the police raided a poker game and Scott ran away. They shot him as he ran, and he died immediately. Witnesses reported to the Omaha World-Herald that the death was unnecessary, and the Omaha Bee called the shooting as reckless and indiscriminate, noting it as the “crowning achievement” of a “disgraceful and incompetent” Omaha Police Department.

Tom and Agnes and Milton Lynched Will

Agnes Loebeck was born in 1899 in Omaha. Her father was Joseph Henry Loebeck (1860-1935), and her mother was Frances Christina Loebeck (1864-1932), both of whom were born in Germany. They had seven children, including Agnes Marie (1899-1966). The family lived at 3228 South 2nd Street in Omaha. On September 25, 1919, Agnes told the Omaha Police Department that she and her reportedly handicapped boyfriend Milton John Hoffman (1897–1982) were assaulted by an African American man at South 5th and Scenic Avenue. Hoffman lived at 1923 S. 13th St, and they were reportedly walking home from a theater.

A blatantly racist Omaha Bee headline screamed, “The most daring attack on a white woman ever perpetrated in Omaha, the most recent act in a series of violent offenses conducted by the Negro on Caucasian females in the city, occurred one block south of Bancroft Street near Scenic Avenue in Gibson two nights ago. Pretty little Agnes Loebeck was assaulted by a negro she identified as William Brown while returning home in company with Milton Hoffmann, her fiancée, a cripple and decorated war veteran.”

Before 1919, Hoffman was supposedly in New Orleans as a two-time bare-knuckle boxing champion called “Barrel.” He was said to have led a mob to the courthouse while riding on their shoulders and waving a handgun, goading on the white hoard to commit the lynching.

Police arrested a Black worker named Will Brown (1878-1919) as the assailant, accusing him of using a handgun during the supposed crime. During a jail interview, police found out his job was to move coal from trucks into cellars. They made a note that Brown limped because of chronic rheumatism. Previously, he work as a heavy laborer in a packinghouse and a lumberyard. Brown’s hands constantly writhed in pain and his body was regularly bent over.

From the outset, it seemed several members of the police force were accused of being sympathetic to Tom Dennison, who also had Milton Hoffman on his payroll; who also lost the previous mayoral election to a reform candidate; who also had deep investments in ensuring his control over the city’s criminal and political machinery. That was the point when all fingers start pointing in the same direction.

Rioting, Lynching and Chaos

According to Orville Menard’s definitive book called River City Empire: Tom Dennison’s Omaha, the notorious political boss was behind the lynching. He orchestrated the men in Black face who committed the crime; the angry mobs that showed up at the Loebeck family home to get Brown early; the horse rider hollering and Milton’s call for vengeance while waving a gun. Omaha had voted in a reform-minded mayor in Ed Smith, and Tom Dennison wanted to punish the city for it. Under the guise of the Red Summer that soaked America’s soil with the blood of hundreds of African Americans nationwide, Dennison stoked Omaha’s white supremacy with startling headlines from the newspapers and more. One of the main flash points was the police department.

Because of the false reports by the Omaha Bee newspaper and false calls to the police station from around the city all summer, the police initially ignored the report from the Loebeck family, including rumors she was murdered.

The morning after Brown was arrested, a crowd of 40 men gathered outside the Douglas County Courthouse and started chanting for Will Brown to be lynched. Within hours, Hoffman led a crowd of 300 people marching north from Bancroft School in South Omaha.

The mobs gathered at the Courthouse, and eventually the crowd of 10,000 swelled to 20,000. During the entire horrific event, Tom Dennison probably maintained control over the machinations of the mob from his offices at the Budweiser Saloon on Douglas Street.

As soon as they were prodded by the Omaha City Council to take action though, the police quickly moved: Ordered to take action on 9/26, the police immediately arrested 45 African African men. Almost all of them were immediately released except Will Brown. He was and taken to the Loebeck house for identification (9/26); a smaller white mob gathered outside her house (9/26); Brown was taken jail at the Douglas County Courthouse (Omaha) (9/26); a group of 25 African American workers was thrown on a train and told to leave the city (9/27); a mob of 10,000 to 20,000 white people gathered outside the courthouse (9/27); they nearly lynched Omaha mayor Ed Smith (9/27); they raided the building and broke out Will Brown (9/27); and they tortured, dismembered, burned and dragged around Brown’s body in downtown Omaha and beyond (9/28).

The mob threw fire bombs, poured gasoline, and barraged the Douglas County Courthouse with more than 10,000 rounds of ammunition. In addition to lynching, dismembering, burning and desecrating Will Brown’s body, they also murdered at least one other African American who was walking on the streets and caught by the mob; wounded at least 20 policemen; and demolished at least 10 homes in the Near North Side neighborhood.

After the Lynching of Will Brown

The white mob turned north toward the city’s African American neighborhood in the Near North Side, assaulting any Black person they saw along the way, as well as smashing windows and assaulting police (9/28). Rumors and newspaper reports said Black people from across North Omaha had raided businesses along North 24th Street for guns, and that there were more than 10,000 armed African Americans on roofs and in hiding spots throughout the Near North Side.

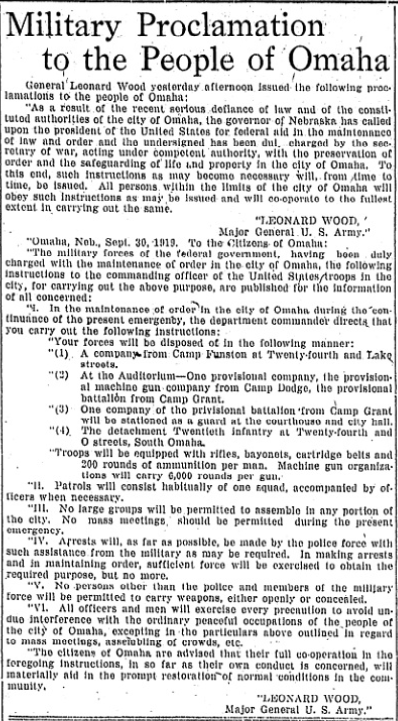

When the white mob arrived at 24th and Cuming Streets, they were met by US Army soldiers who’d been called to the city from Iowa, Missouri and Fort Omaha (9/28). On October 1, 1919, the commander of the operation, US Army Major General Leonard Wood, declared martial law over the city.

From several stations and field stations around Omaha, General Wood commanded more than 300 US Army soldiers to be garrisoned at 24th and Lake Streets among other places. During their occupation of North Omaha, the US Army ordered 18 large machine guns along Cuming Street, North 16th, North 30th, and Lake Streets, with soldiers encamped and on patrol along these lines. An observation balloon was launched from the Fort Omaha Balloon School, manned by soldiers looking for fires that might be started inside the redlined area. The other two camps were on South 13th Street and in South Omaha.

Milton Hoffman was accused of inciting the riot, but went to live in Denver for a short time before marrying Agnes in 1920. He was supposedly helped by Tom Dennison. In April 1921, former mayor Ed Smith gave a speech at the Auditorium saying that Agnes Loebeck hadn’t been attacked by Will Brown. Two days later, Milton Hoffman gave a statement to the Omaha World-Herald saying she had, and that Smith was lying. Smith also said the riot was pre-orchestrated, which Hoffman also opposed.

120 indictments were handed down by a grand jury investigating the riot starting on October 8, 1919. There were confessions, witnesses and extensive interrogations that lasted for weeks in court. However, only two men were charged with a crime: Claude Nethaway, a notoriously racist real estate agent in Florence, and a man named George Davis.

Even the Omaha Bee stood trial for its role inciting the riot, including its editor Victor Rosewater, who routinely practiced yellow journalism. However, all suspects were eventually released, and nobody served time. The grand jury did find the police captain innocent of making the situation worse, and congratulated Mayor Smith for his heroics. However, they found Chief Eberstein and the Omaha Police Department guilty for exacerbating the riot by neglecting to staff the courthouse correctly.

Louis Weaver was the first of the rioters convicted by district Judge William A. Redick. On December 13, 1919, Weaver was sentenced to 20 years in the Nebraska state penitentiary.

General Wood left the city on October 6, 1919. His troops, who came from several locations, didn’t return to their bases until after October 15th. They came from Fort Omaha, Camp Dodge, Camp Funston and Camp Grant. Meanwhile, the general’s tune changed. After originally attributing the riot to Tom Dennison’s criminal machine, he later blamed organized labor and the Bolsheviks. He would later use that fear in his 1920 presidential campaign.

In a 1919 article from The Crisis called “The Real Causes of Two Race Riots,” reports said that Agnes Loebeck knew Will Brown as a prostitute. Apparently she had problems with Brown, and wanted to get revenge on him by alleging the assult. The article also said Dennison was behind the riot as an attempt to regain political control of the city.

Will Brown was buried in the Potter’s Field near Young Street and Mormon Bridge Road on October 2, 1919. There were no mourners, there was no service, and for more than 80 years there was no grave marker placed there.

In 1921, Tom Dennison’s “perpetual mayor” Jim Dahlman was reelected to his position. One of the first things to happen was the dismissal of all remaining charges relating to the lynching of Will Brown, and in September 1921, all the books were cleared.

What Happened to Agnes Loebeck Hoffman?

As late as 1931, Milton Hoffman was said to be a member of city boss Tom Dennison’s inner circle. From 1945 to 1954, Milton was a secretary to various Omaha City Commissioners, and from 1964 to 1965, he was the coordinator of services at the Omaha City Hall.

The Hoffmans had several children, and some of whom as well as their offspring still live in the area. When she died in 1966, Agnes and Milton lived at 2445 South 17th Street. In 1973, Milton was remarried to Edna Swanson. He died in 1982. Agnes Loebeck Hoffman and Milton Hoffman are buried at Westlawn-Hillcrest Funeral Home and Memorial Park in Omaha.

The Impacts

There were countless impacts from the lynching of Will Brown. While it started beforehand, massive distrust between Omaha’s Black and white communities flared a century ago, and continues today. Informal Jim Crow still rules Omaha, with clear color lines between residential, commercial, religious and cultural activities still informally enforced.

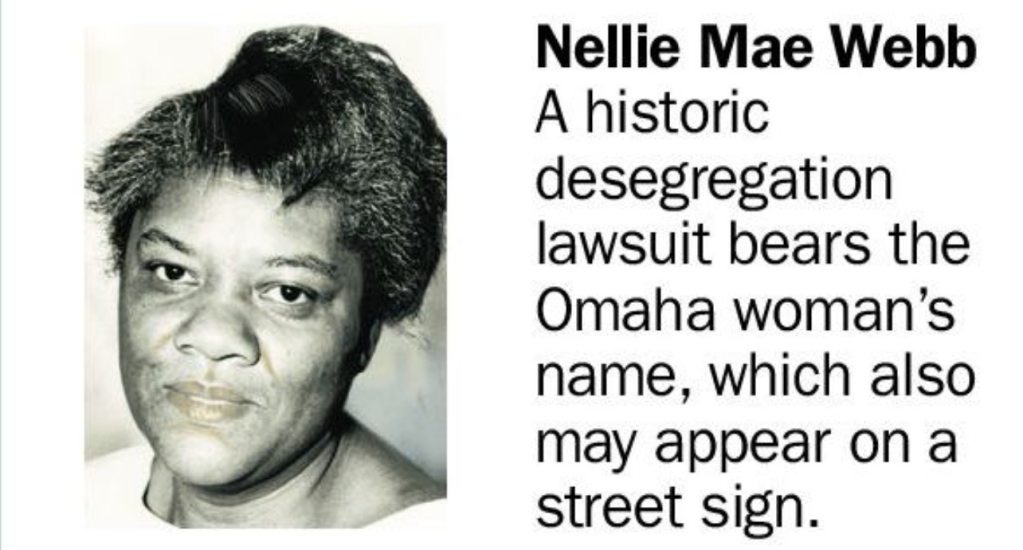

Perhaps the most directly observable consequence of the lynching of Will Brown was the absolute segregation of Omaha. While the city was segregated beforehand, afterwards it was strictly segregated. When the US Army drew the redline around the Near North Side, they effectively drew a line followed, reinforced and sustained by real estate agents, insurance brokers, bankers and property owners for more than 40 years after. The residential patterns and behaviors established then continue today.

In 2011, Chris Herbert, an African American from Los Angeles who’d never been to Omaha, bought a gravestone for Will Brown.

In 2021, there was a commemoration of the lynching of Will Brown with an installment of a historical marker to acknowledge the lynching of Will Brown and the riots. It is located at the Douglas County Courthouse, 1701 Farnam Street.

People Involved in the Lynching of Will Brown

These are just some of the people associated with the lynching of Will Brown.

- Will Brown (1878-1919)—African American laborer lynched in Omaha on September 28, 1919 who suffered severe rheumatism.

- Tom Dennison (1858-1934)—Omaha’s political boss from 1890-1930 who likely orchestrated the lynching of Will Brown.

- Ed P. Smith (1860-1930)—The reformist mayor of Omaha nearly lynched by the white mob who requested US Army intervention in the riot.

- Agnes Loebeck Hoffman (1899-1966)—First generation German immigrant woman who accused Will Brown of assaulting her; may have been a prostitute.

- Milton J. Hoffman (1897–1982)—Employee of Dennison, date of Agnes Loebeck at time of supposed assault by Will Brown, may have been handicapped.

- Joseph H. Loebeck (1860-1935)—German immigrant father of Agnes.

- Frances C. Loebeck (1864-1932)—German immigrant mother of Agnes.

- Leonard Wood (1860-1927)—US Army Major General who intervened at the request of the Omaha mayor and Nebraska governor and imposed martial law on the city; later ran for president.

- Samuel R. McKelvie (1881-1956)—Nebraska governor who requested US Army intervention in the Omaha riot.

- Claude L. Nethaway (1867-1937)—Virulent racist real estate agent who incited the mob and was tried for the murder of Brown, but acquitted. Allegedly gave the rallying call to lynch Will Brown.

- Victor Rosewater (1871-1940)—Editor of Omaha Bee who used yellow journalism to sell papers, which helped incite the rioting that led to the lynching of Will Brown.

- J. Dean Ringer (1878-1931)—Omaha Police Department commissioner who was committed to cleaning up Tom Dennison’s crime circle.

- William Francis (1902-1952)—A 16-year-old relative of Agnes Loebeck who rode a horse into the mob to incite crowds to attack the courthouse.

- Marshall Eberstein (1859-1946)—The Omaha chief of police who was assaulted by the crowd when he spoke to them, asking for justice to take its course.

- Louis Weaver (n.d.-n.d.)—On December 13, 1919, Weaver became the only criminal sentenced to serve for his actions. Judge Redick gave him 20 years in the Nebraska state penitentiary for his role in the riot.

- William A. Redick (1859-1936)—Omaha district judge who tried several rioters.

Locations Involved in the Lynching of Will Brown

- 3228 South 2nd Street—This was the Loebeck family home, where Agnes lived at the time.

- 1923 South 13th Avenue—This was where Milton Hoffman lived at the time.

- Bancroft Street and Scenic Avenue—The location of where Agnes Loebeck was allegedly assaulted.

- 1811 South 5th Street—Will Brown lived with Virginia Jones at “5th and Cedar” when the mob gathered to lynch him there on September 27th. Police came and supposedly found him under his bed.

- 317 South 15th Street—The location of Tom Dennison’s exclusive office where he likely orchestrated the day’s events.

- Bancroft School, 2724 Riverview Blvd—The location where the first major mob of 300 people gathered to march to the Courthouse.

- Douglas County Courthouse, 1701 Farnam Street—Will Brown was held in a top-floor jail. This was the major site of rioting, and was nearly destroyed by the rioters. Mayor Ed Smith spoke to the crowd from the front steps and was nearly lynched from this place, too.

- Intersection of 16th and Farnam Streets—A 12-year-old named Verne Joseph directs traffic at this major intersection for several hours during the riot.

- Intersection of Eighteenth and Harney Streets—Will Brown was lynched from streetcar cables intersecting here.

- 17th and Dodge Streets—Location of the burning of Will Brown’s corpse.

- Potter’s Field, near Young Street and Mormon Bridge Road—Location of Will Brown’s burial and grave marker.

- North 24th and Lake Streets—Location one of four of US Army field stations maintained starting October 1, 1919 during the occupation of the Near North Side.

- South 24th and O Streets—Location two of four of US Army field stations maintained starting October 1, 1919 for the suppression of the South Omaha rioters.

- Douglas County Courthouse—Location three of four US Army field stations maintained starting October 1, 1919 .

- Omaha City Hall—Location four of four US Army field stations maintained starting October 1, 1919.

- Fort Omaha, at North 30th and Fort Streets—One of the four stations maintained by the US Army starting October 1, 1919.

- Omaha Auditorium, South 15th and Howard Streets—The second of four stations maintained by the US Army starting October 1, 1919.

- South Omaha City Hall, 5002 South 24th Street—The third of four stations maintained by the US Army starting October 1, 1919.

- Omaha Police Station—The fourth of four stations maintained by the US Army starting October 1, 1919.

- Lynching Marker—In 2020, a historical marker was placed at the Douglas County Courthouse site where Will Brown was lynched on September 27, 1919. Located at 1701 Farnam Street.

MY ARTICLES ON THE HISTORY OF CRIME IN NORTH OMAHA

Crimes: 1891 George Smith Lynching | 1909 Unsolved Murder | 1910 Jack Johnson Riot | 1917 Larkin McCloud Case | 1919 James Smith Death | 1919 Will Brown Lynching | 1969 Vivian Strong Killing | 1960s North Omaha Riots |

Events: Bombings | Mob Violence

Criminals: Early 20th Century Crime Bosses | Vic Walker | Ollie William Jackson | Axe Murderer Jake Bird

Related: Black Police in Omaha | Police Brutality | Antisemitism | Racism

Elsewhere in Omaha: 1906 Murder of Ed Flurry | 1899 Kidnapping of Ed Cudahy | 1890 Pinney Farm Murders

You Might Like…

- The Lynching of George Smith

- A History of Mob Violence in Omaha

- A Timeline of Race and Racism in Omaha

Elsewhere Online

- “Omaha race riot of 1919” article on Wikipedia

- Walk Well Through The Fire blog by Nicholas Paine

- “Omaha Courthouse Lynching 1919” by BlackPast.org

- “The Omaha Riot of 1919” by Arthur V. Age in 1964 for Creighton University.

- “Lest We Forget: The Lynching of Will Brown, Omaha’s 1919 Race Riot” by History Nebraska on February 23, 2018

- “A Horrible Lynching” by NebraskaStudies.org for NET

- “Omaha Race Riot” in the Encyclopedia of the Great Plains

- “Infamous 1919 Omaha riot still offers lessons” by the Omaha World-Herald, September 16, 2017

Sources

- Black America: A State-by-State Historical Encyclopedia [2 volumes]: A State-by-State Historical Encyclopedia by Alton Hornsby, Jr. (2011).

- Omaha World-Herald

- Omaha Bee

ADDITIONAL ITEMS

This image is from the September 30, 1919 edition of the Omaha Bee. The caption says, “Note thrown to mob from court house jail.” The purported note says, “The judge says he will give up negro Brown He is in dungeon there are 100 white prisoners on the roof_save them.”

*Agnes Marie Loebeck Hoffman was also referred to as Agnes Lobeck, Agnes Lowback, Agnes Loeback and Agnes Hoffman.

Leave a comment