Omaha’s segregated schools are part of the fabric of the city today. However, few people will admit that Jim Crow made Black schools here, or that racial segregation continues existing in Omaha Public Schools, or that white people continue benefiting from the racial imbalance of the city’s public education system. This article is a history of segregated schools in Omaha.

As white flight gripped North Omaha, white families ripped their children from historically white and mixed schools and placed them in all-white public schools in west Omaha, as well as private schools spread throughout the city. This led to the segregation of public schools in North Omaha.

Racism in Omaha Public Schools isn’t confined to student placement. It isn’t just a historical fact, either. Today, racism in Omaha continues to be prevalent in teacher hiring, school leadership, district leadership, school board elections, school curriculum and teaching practices, testing, and discipline.

This article is limited to addressing the first issue of segregating student populations; however, the other issues should be addressed too.

A few terms before I start:

- Racial segregation: The separation of humans into racial or other ethnic groups in daily life.

- De facto segregation: Discrimination that was not segregation by law, instead relying on culture, attitudes, traditions and opinions for enforcement.

- De jure segregation: Law provides entirely separate schools for black and white students that they legally have to attend.

- Jim Crow: The practice of segregating black people in the US.

There were at least two instances of de jure segregation in Omaha’s history: The first was the Omaha Colored School from 1865 to 1872, and the second was the Catholic Archdiocese of Omaha’s school for Black students only called St. Benedict School from 1928 to 1968.

Omaha Public Schools are de facto segregated, which is enforced by housing practices, economic limitations and cultural “understandings.” Following is an exploration of what Jim Crow look like in Omaha Public Schools historically, and where it appears today.

School Segregation in Pioneer Omaha

The Nebraska Territorial Legislature felt comfortable blatantly discriminating against students of color in a 1856 law stating,

“It shall be the duties of the directors… to take… an enumeration of all the unmarried white youths… between the ages of five and twenty-one years… for the purpose of affording the advantage of free education to all the white youth of this territory, the territorial common school fund shall hereafter consist of such sum as will be produced by the annual levy and assessment of two mills upon the dollar valuation on the grand list of the taxable property of the territory…”

—Section 60, 5th Session of the Territorial Legislature, Complete Neb. Sess. Laws, 1855 to 1865, 92 (1886)

Black people weren’t counted or taxed for public school purposes until 1867. Early that year, a group called the Educational Association met in Omaha and proposed, “That the Legislative Assembly of Nebraska ought to amend the School Laws so as to provide for the education of colored children in this Territory.” The group shared this in the Nebraska Territorial Legislature, which met in Omaha, as a “Bill to Remove all Distinctions on account of race or color in our public schools.”

The Legislature rejected the proposal though, stating,

“The people of Nebraska are not yet ready to send white boys and white girls to school to sit on the same seats with negroes; they are not yet ready to endorse in this tacit manner the dogma of miscegenation, especially are they yet far from ready to degrade their offspring to a level with so inferior a race.”

—January 25, 1867, House Journal 95 (12th Terr. Sess. 1867)

With anti-slavery Republican Territorial Governor Alvin Saunders gone from the Territory on business, Territorial Secretary A.S. Paddock added his rejection to the bill writing, “Permit me, however, to suggest that better results could be expected in the education of both white and colored youths, if separate schools could be provided for each.”

There is evidence that Black students were enrolled in Omaha’s public schools as early as 1865. Starting that year, a segregated school for Black students was held downtown in an old shack that was literally falling over. It was the Omaha Colored School.

When the Omaha School District re-organized in early 1872, the Daily Herald called for separate but equal schools, and the Omaha School District instituted a policy for Jim Crow schooling by renting a heated room on 10th Street between Dodge and Douglas to use as the new official “colored school.” That year, there were 1,576 students in nine public schools in Omaha. 47 Black students total attended eight of those schools, with 25 of them at the “colored school.”

Led by community leader Edwin Overall, a number of African American parents challenged the district segregation policy. Their advocacy worked, and in the fall of 1872, the Jim Crow school was permanently closed and Black students were sent to the schools nearest to their homes. These homes were spread out; however, the vast majority of African American students lived and went to school north of Dodge Street, and at that point, east of North 24th Street.

Early History of School Segregation in Omaha

North Omaha was home to all of the city’s strictly segregated Black schools. Over time, those became identified as

all of which were the only elementary schools serving African American students. In Omaha, as well as many cities nationwide) schools for Black students were older, had fewer resources of all kinds, and paid their teachers less than in white schools.

Overtly Racist District Leaders

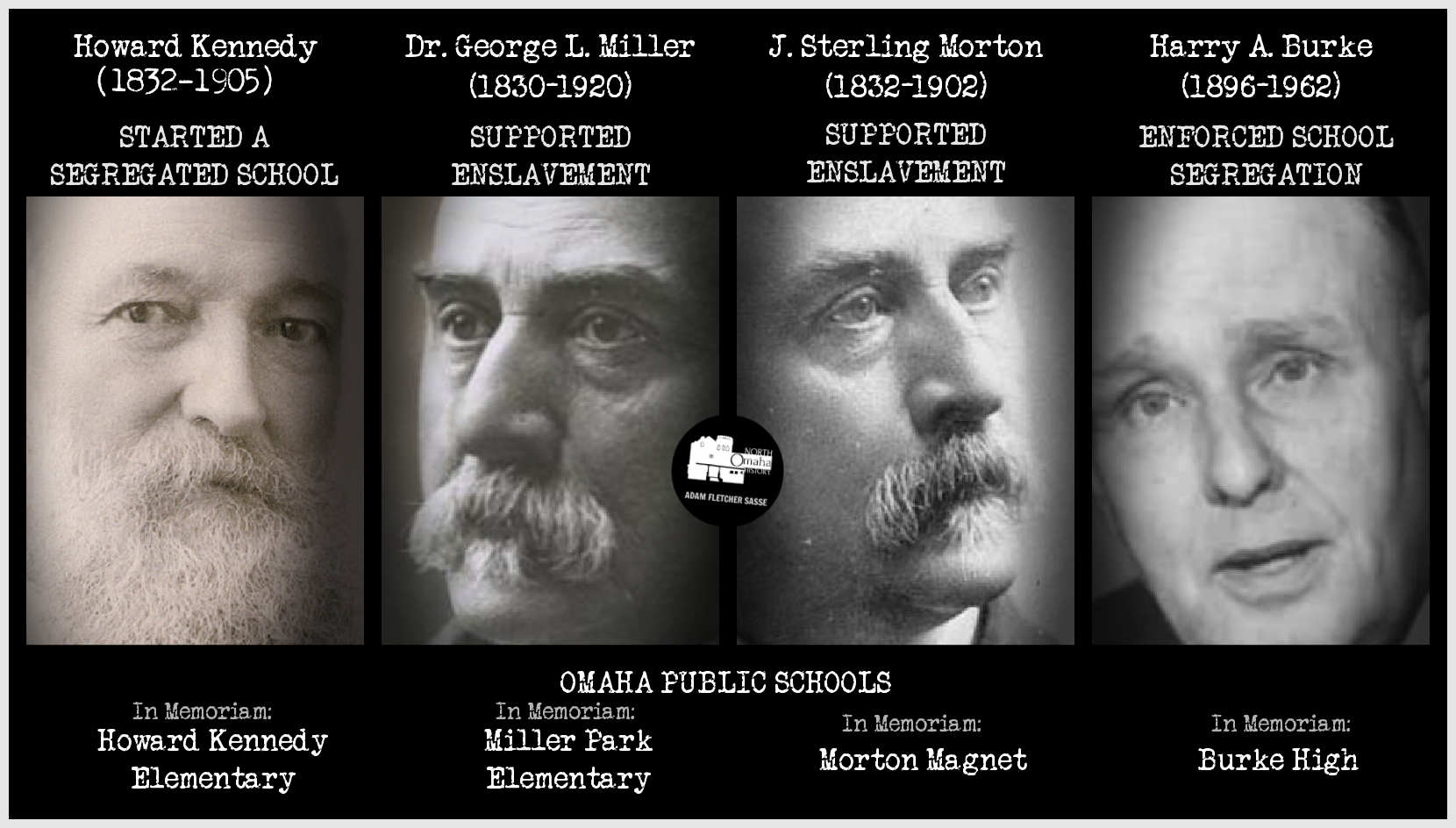

Throughout its 160+ year history, there surely have been several racist superintendents, including the city’s first person in the position. In 1859, Howard Kennedy

However, towards modern times an overtly racist Omaha superintendent had the honor of a high school being named after him.

Dr. Harry A. Burke, namesake of Omaha Burke High School, used racism to run Omaha Public Schools from 1946 to 1962. David Bristow, now an official with the Nebraska State Historical Society, wrote about an interview with Herb Rhodes, a North Omaha civil rights leader in the 50s and 60s. Rhodes said that Harry Burke once “proclaimed that as long as he was superintendent, there would not be a black educator in the school system, other than the two schools that served the black community,” because Burke opposed having black teachers “where white children would see a black person in a role of prominence or authority.”

There were other incidents of Burke’s forked tongue showing, including newspaper accounts and a lot of personal anecdotes from faculty and students. During his tenure, Burke strictly segregated schools, denied Black students to attend white schools, wouldn’t hire Black teachers, would only hire Black teachers for Black schools, wouldn’t allow Black principals to supervise white teachers, denied funding relief for overcrowded Black schools, and was almost single-handedly responsible for the district being sued by the US government for racial segregation.

All of that is why it seems surprising today that in 1967, a new high school was completed in a cornfield on the outskirts of Omaha with the explicit purpose of promoting white flight from North Omaha. While it seems right that this specific building in this location for this reason was named after an overt racist, today it is clearly inappropriate and the name should be changed immediately.

Omaha’s Negro School Board

In February 1968, African Americans in Omaha formed a “Negro School Board” to dismantle white supremacy in Omaha Public Schools. Members of the Negro School Board were Mike Adams, Ernie Chambers, Ruth Jackson, Raymond Metoyer, Wilbur Phillips and Charles Washington.

Their primary objectives were to:

- Facilitate the immediate desegregation of all schools;

- Insurance of proper channeling of Federal, state and local school funds to problem areas;

- Establishment of a board of appeals for parents seeking redress of grievances;

- Uplift of standards and quality of education through improvement of programs, facilities and training;

- Promote vehicle for registering and fielding of complaints and suggestions, and;

- Promotion of the incorporation of courses and materials which present achievements, culture and history of Blacks in America into the regular citywide school curriculum.

There was no further mention of this group after its formation though. Of course, member Ernie Chambers has continued to fight for justice to this day, along with several other members of the group.

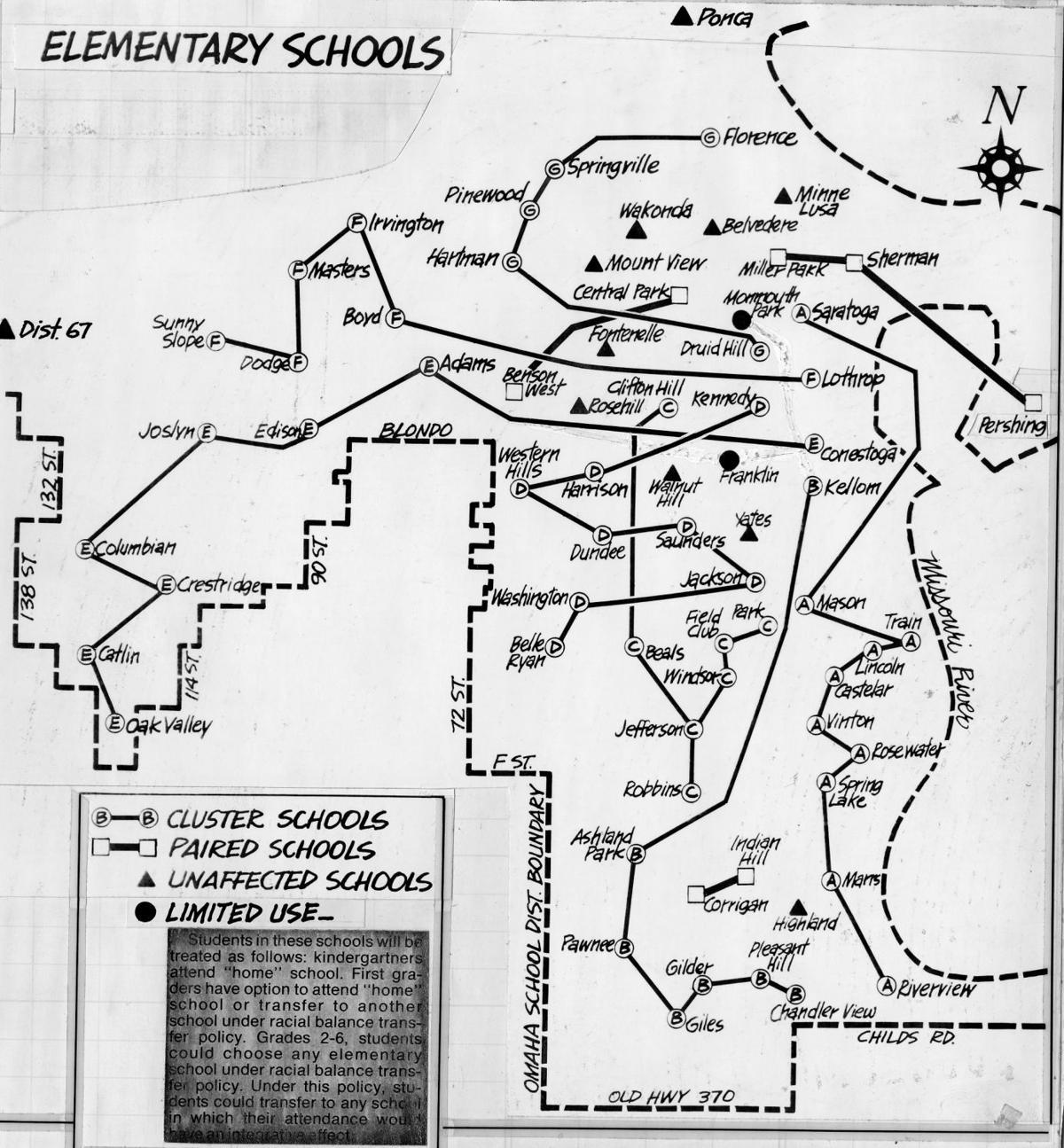

Omaha’s Desegregation Plan

In 1972, the total number of students in Omaha Public Schools was 63,125. That included 19.4 percent blacks, 1.6 percent Hispanics, 0.6 percent American Indians, and 0.3 percent Asian Americans. Of 2,585 faculty members in 1972, there were 202 blacks, 8 Hispanics, 5 Asian Americans, and 1 American Indian. During the 1977-78 school year, 1 of 12 school board members was black.

In 1976, the US government took the Omaha Public Schools to court because of its segregated schools. The US circuit court ordered Omaha to use busing to desegregate the district. They ordered the district to desegregate Omaha’s public schools, starting in September 1976. Suddenly, white flight swept through North Omaha, with hundreds of residents fleeing to the city’s western suburbs where there were few African Americans. White student enrollment in the district tanked, and African-American students were encouraged to travel across the city to predominantly white schools.

In 1999, the school district adopted an open enrollment policy based on income instead of race, effectively ending busing. Resegregation has emerged throughout the 2000s. When state legislator Ernie Chambers promoted legislation to create three distinct learning communities controlled by Omaha neighborhoods organized largely around patterns of race and ethnicity, the conversation about race and education policy came back on the radar in the city.

Resistance to Segregation

There was significant and sustained resistance to Omaha’s racial segregation in schools. Starting in with Edwin Overall’s 1872 campaign to end the Omaha “Colored School,” Black parents have advocated, activated, organized and won several efforts to stop white supremacy within OPS.

In the 1970s, a group of mothers became synonymous with attempts to force Omaha schools to integrate. Through their tireless campaigning, Lerlean Johnson, Zenolia Hilliard, Lillie Gunter, Irene Gunter, Charlotte Stropshire, Nellie Mae Webb, and Dorothy Eure successfully forced the launch of Omaha’s first attempt to racially integrate it’s schools.

Continuing to Ernie Chambers’ sustained work from the 1960s through the 2020s, African Americans in Omaha have been working to stop Jim Crow and address white supremacy in Omaha Public Schools in nearly countless ways.

The struggle continues today with a campaign to renamed Burke High School, a fight to recognize Black history and more throughout curriculum, and efforts to end racist mascots in the district’s schools.

Re-segregation in Omaha Schools Today

Since the release of Omaha from the order by the US Supreme Court to become integrated in 1999, Omaha Public Schools have become re-segregated. According to OPS data, percentage of white students enrolled in Omaha Public Schools is decreasing while the percentage of students of color is rising, especially in schools with predominantly African American and Hispanic / Latino student populations. This is happening while the general Omaha population has increasing numbers of white people and a decreasing population of African Americans.

Modern Racial Statistics

According to the U.S. Department of Education, the 2018-2019 racial demographics for Omaha Public Schools are:

- Hispanic or Latino: 10,648

- Non Hispanic or Latino: 73,217

- Students of one race: 80,257

- White alone: 53,974

- Black or African American alone: 18,578

- American Indian or Alaska Native alone: 861

- Asian alone: 1,160

- Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander alone: 49

- Some other race alone: 5,635

A variety of schools in North Omaha have large percentages of African American students that demonstration racial unevenness in school. For instance, at North High, Blackburn High, and Northwest High, African American students comprise the largest racial populations in the school. Other schools that are predominantly African American include Hale, King, Monroe, Morton, and McMillan; as well as the Transitions Program, Career Center and Parrish, which are also predominantly African American. In the 2015-16 school year, the trends of racial isolation in Omaha Public Schools are even more pronounced in elementary schools. Belvedere, Central Park, Conestoga, Druid Hill, King, Franklin, Lothrop, Miller Park, Mountain View, Saratoga, Skinner and Wakonda are all majority African American schools.

The UNO Middle College Program and the Gateway to College Program are predominately white, as well as Burke High, Alice Buffet Middle, and Davis Middle. Vastly white student populations also exist at Caitlan, Columbian, Dundee, Florence, Fullerton, Picotte, Pinewood, Saddlebrook, Standing Bear, and Washington elementary schools.

This is all evidence of the ineffective administration of resources among Omaha Public Schools, and demonstrates how North Omaha is routinely afflicted by racial segregation. A more thorough analysis of per school spending, neighborhood economic status or other factors would corroborate these findings.

In the meantime, its easy to see that racial segregation is trending throughout the city of Omaha today, and that its schools are clearly reflective of that trend.

Directory of Historically Segregated Schools in Omaha

Segregation in Omaha Public Schools has been generally confined to a group of schools north of Dodge Street and east of North 72nd Street. As de facto segregation, Black students are limited to only attending schools in the neighborhoods where they live. In Omaha, housing is limited to African Americans according to their income, which in turn is afforded by income and credit. Income and credit are reliant on education.

This cycle disallowed several generations of Blacks to move away from the segregated schools their children attended; these schools hosted succeeding generations of African American students. Even when the Black population was allowed to move away from the Near North Side by the 1964 Fair Housing Act, school segregation in Omaha moved along with the Black population. This has led to the simplistic reality that wherever African Americans live, Black students attend the schools in those neighborhoods. This has allowed Omaha Public Schools to stay segregated by allowing white people to simply move away from schools Black students attend. This has proven to be the case over the last 50+ years since housing integration.

Early Black Schools in Omaha

The following schools were identified as “Black schools” in the history of Omaha dating back to the 1880s and extending into the 1960s.

- Howard Kennedy School, 2906 North 30th Street

- Lake School, 2410 North 19th Street

- Kellom School, 1311 North 24th Street

- Lothrop School, 1518 North 26th Street

- Long School, 2520 Franklin Street

Later Black Schools in Omaha

In 1976, the US Supreme Court identified the following schools as segregated and ruled that Omaha Public Schools integrate the students in these buildings.

- Tech High School, 3215 Cuming Street

- Tech Junior High School, 3215 Cuming Street

- Mann Junior High School, 3720 Florence Boulevard

- Webster Elementary School, 618 North 28th Avenue

- Franklin Elementary School, 3506 Franklin Street

- Howard Kennedy Elementary School, 2906 North 30th Street

- Fairfax Elementary School, 3708 North 40th Street

- Druid Hill Elementary School, 4020 North 30th Street

- Monmouth Park Elementary School, 4508 North 33rd Street

- Saratoga Elementary School, 2504 Meredith Avenue

- Lothrop Elementary School, 3300 North 22nd Street

- Lake Elementary School, 2410 North 19th Street

- Connestoga Elementary School, 2115 Burdette Street

- Kellom Elementary School, 1311 North 24th Street

Today’s Black Schools in Omaha

According to recent data, there are several schools in Omaha Public Schools today that are predominantly African American, despite the currently segregated schools in Omaha have included or currently do include…

- North High School, 4410 North 36th Street

- Blackburn High School, 2606 Hamilton Street

- Northwest High School, 8204 Crown Point Avenue

- Hale Middle School, 6143 Whitmore Street

- Monroe Middle School, 5105 Bedford Avenue

- McMillan Magnet Center, 3802 Redick Avenue

- Transitions Program, 2504 Meredith Avenue

- Career Center, 3230 Burt Street

- Parrish Program, 4315 Cuming Street

- Belvedere Elementary School, 3775 Curtis Avenue

- Central Park Elementary School, 4904 N 42nd Street

- Conestoga Elementary School, 2115 Burdette Street

- King Elementary School, 3706 Maple Street

- Miller Park Elementary School, 5625 N 28th Avenue

- Mountain View Elementary School, 5322 N 52nd Street

- Skinner Elementary School, 4304 N 33rd Street

- Wakonda Elementary School, 4845 Curtis Avenue

Note that I didn’t pick from North Omaha’s schools only; its coincidental to my list that all of Omaha’s segregated schools are in North Omaha.

Schools in Omaha are clearly re-segregated today. More white students in Omaha attend private schools within the city’s boundaries than ever before. Fewer teachers of color are available for students of color and white students than ever before.

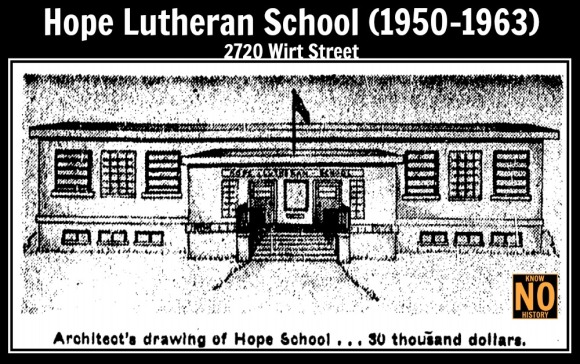

Private Segregated Schools

There were at least two private segregated schools in Omaha’s history. The first was St. Benedict’s Catholic School, which was located at North 24th and Grant Street and operated for 40 years as a school exclusively for African American students who Catholics did not want integrating with white students.

The other was Hope Lutheran School, which was operated for 14 years by Hope Lutheran Church. It was “coincidentally” segregated because it served only neighborhood students from the neighborhood around its building at North 27th and Wirt Streets, which was wholly Black during the school’s existence.

Segregation in Suburban Omaha

Suburban school districts around Omaha also grow exponentially. This is happening because of population growth on the edges of the city, because even as their municipalities are annexed by the City of Omaha, their school districts are not absorbed by Omaha Public Schools. This has been true of Elkhorn Public Schools, Arlington Public Schools, Bennington Public Schools, Ralston Public Schools, Westside Community Schools, and Millard Public Schools. Neighboring Bellevue Public Schools has grown exponentially, too.

With recent struggles still in the rear view mirror, it is absolutely necessary to keep moving forward. Only time will tell whether that will happen though.

Omaha Schools Named for Racists

Throughout Omaha Public Schools today, there are several schools named for racists. Some of them include Burke High School, Morton Middle School, Miller Park Elementary, and perhaps most egregiously, Howard Kennedy Elementary.

In 1867, the Nebraska Territory governor asked the legislature to consider a “revision or amendment of the school law” to allow Black children to attend public schools. For a decade before that Black students were denied entry to schools in Omaha and elsewhere. The legislature did what the governor asked; however, the law didn’t specify whether the schools should be integrated, and racist school leaders in Omaha took the opportunity to create a segregated school for Black children. The Omaha School District created a so-called “colored school” which served at least 27 students from 1865 to 1872. The superintendent who would have made that decision for Omaha Public Schools then was Howard Kennedy (1849-1914). In 1910, a new school building for the old Omaha View School was named in honor of him, and today the Howard Kennedy Elementary School continues serving a predominantly African American student body, as it’s done for more than 70 years.

Today, J. Sterling Morton (1832-1902) is recognized as an important Nebraska statesman, federal government leader, and the founder of National Arbor Day. However, during his life he made it known he was also a deep racist who stood really committed to white supremacy, for enslavement, against equality, and with the South before and after the Civil War. In 1865 he wrote, “It will be more manly to accept negro suffrage by legal enforcement than to humiliate ourselves by its voluntary adoption as the price of admission to the Union… We take n—-r only when forced to it by Congress and therefore are for remaining at present a territory.” In 1965, Omaha Public Schools named a new junior high school for him, and Morton Magnet School continues by that name today.

When a territorial legislator from Otoe County named William H. Taylor (1827-1865) introduced the first bill to end slavery in Nebraska in 1859, Dr. George Miller (1830–1920) protested as a Nebraska legislator. He claimed slavery did not exist in the territory, and if it did what right was it of the government to take away private property? Taylor responded saying, “There has never been a federal officer… in this territory who has not brought with him into the territory a negro or negroes who have been and are now held in slavery.” Taylor also enumerated several businessmen who kept slaves. After a newspaper in Omaha called the Daily Nebraskian published its support of slavery, the anti-slavery proposal failed. Dr. Miller went on to establish the Omaha Daily Herald, which later became part of the Omaha World-Herald. Taylor is largely forgotten today, and Dr. Miller has Miller Park Elementary School named in his memory.

Dr. Harry A. Burke (1896-1962) was a superintendent who used racism to run Omaha Public Schools for 15 years, from 1946 to 1962. David Bristow, now an official with the Nebraska State Historical Society, wrote about an interview with Herb Rhodes, a North Omaha civil rights leader in the 50s and 60s. Rhodes said that Harry Burke once “proclaimed that as long as he was superintendent, there would not be a black educator in the school system, other than the two schools that served the black community,” because Burke opposed having black teachers “where white children would see a black person in a role of prominence or authority.” Omaha’s In 1967, Harry A. Burke High School was named in his memory five years after he died, and a 2020 movement to rename the school in 2020 received no traction within the Omaha school board. The high school continues honoring this racist as of 2023.

Other schools in OPS are named also problematically. General William T. Sherman (1820-1891), a leader of the US Army during the Civil War, was an avowed white supremacist and has been memorialized by Sherman Elementary since the 1880s. John H. Kellom (1817-1891) was an early Omaha School Board member and the first principal of Omaha High School who prevented Black students from attending the school for several years. Kellom Elementary School was named in his memory.

You Might Like…

MY ARTICLES ABOUT SEGREGATION IN OMAHA:

Omaha Black-Owned Businesses | Segregated Schools | Segregated Hospitals | Segregated Hotels | Segregated Churches | Segregated Newspapers | Segregated Baseball

MY ARTICLES ABOUT THE HISTORY OF SCHOOLS IN NORTH OMAHA

GENERAL: Segregated Schools | Higher Education

PUBLIC GRADE SCHOOLS: Beechwood | Belvedere | Cass | Central Park | Dodge Street | Druid Hill | Florence | Fort Omaha School | Howard Kennedy | Kellom | Lake | Long | Miller Park | Minne Lusa | Monmouth Park | North Omaha (Izard) | Omaha View | Pershing | Ponca | Saratoga | Sherman | Walnut Hill | Webster

PUBLIC MIDDLE SCHOOLS: McMillan | Technical

PUBLIC HIGH SCHOOLS: North | Technical | Florence

CATHOLIC SCHOOLS: Creighton | Dominican | Holy Angels | Holy Family | Sacred Heart | St. Benedict | St. John | St. Therese

LUTHERAN SCHOOLS: Hope | St. Paul

HIGHER EDUCATION: Omaha University | Creighton University | Presbyterian Theological Seminary | Joslyn Hall | Jacobs Hall | Fort Omaha

MORE: Fort Street Special School for Incorrigible Boys | Nebraska School for the Deaf and Dumb

Listen to the North Omaha History Podcast on “The History of Schools in North Omaha” »

MY ARTICLES ABOUT CIVIL RIGHTS IN OMAHA

General: History of Racism | Timeline of Racism

Events: Juneteenth | Malcolm X Day | Congress of White and Colored Americans | George Smith Lynching | Will Brown Lynching | North Omaha Riots | Vivian Strong Murder | Jack Johnson Riot

Issues: African American Firsts in Omaha | Police Brutality | North Omaha African American Legislators | North Omaha Community Leaders | Segregated Schools | Segregated Hospitals | Segregated Hotels | Segregated Sports | Segregated Businesses | Segregated Churches | Redlining | African American Police | African American Firefighters | Lead Poisoning

People: Rev. Dr. John Albert Williams | Edwin Overall | Harrison J. Pinkett | Vic Walker | Joseph Carr | Rev. Russel Taylor | Dr. Craig Morris | Mildred Brown | Dr. John Singleton | Ernie Chambers | Malcolm X

Organizations: Omaha Colored Commercial Club | Omaha NAACP | Omaha Urban League | 4CL (Citizens Coordinating Committee for Civil Rights) | DePorres Club | Omaha Black Panthers | City Interracial Committee | Providence Hospital | American Legion | Elks Club | Prince Hall Masons | BANTU

Related: Black History | African American Firsts | A Time for Burning | Omaha KKK | Committee of 5,000

Elsewhere Online

- “The Status and Perceptions of Black School Administrators in Omaha” by Wilbert H. Bledsoe, Oklahoma State University (1984)

- “Editorial: Omaha school segregation,” by Mildred Brown for the Omaha Star.

- United States v. School Dist. of Omaha, State of Nebraska, 367 F. Supp. 179 (D. Neb. 1973)

- “Education in Omaha” by the Making Invisible Histories Visible Project of Omaha Public Schools

- “Law to Segregate Omaha Schools Divides Nebraska” by Sam Dillon on April 15, 2006 for The New York Times.

- “Segregation Nation” by Sharon Lerner on June 9, 2011 for The American Prospect.

- “‘Learning Community’ Nebraska Program Brings Diversity To Some Highly Segregated Public Schools” by Susan Eaton for Huffington Post on January 8, 2013.

- Nebraska Profile – National Coalition on School Diversity

- “‘School transfer case study: Omaha’ in PERSISTENT RACIAL SEGREGATION IN SCHOOLS: Policy Issues and Opportunities to Address Unequal Education Across New Jersey’s Public Schools” for The Fund for New Jersey.

BONUS PICS

Leave a comment