Omaha Public Schools are re-segregating today. Neighborhoods in Omaha are severely segregated. Throughout the city, black and brown people are routinely followed through stores, disproportionately pulled over by police and much, much more. Following, I detail research findings that show the areas of education, healthcare, economic development and policing demonstrate clear racial segregation throughout Omaha. Racism isn’t just a physical phenomenon in Omaha; its a systemic, cultural and attitudinal reality present throughout the city.

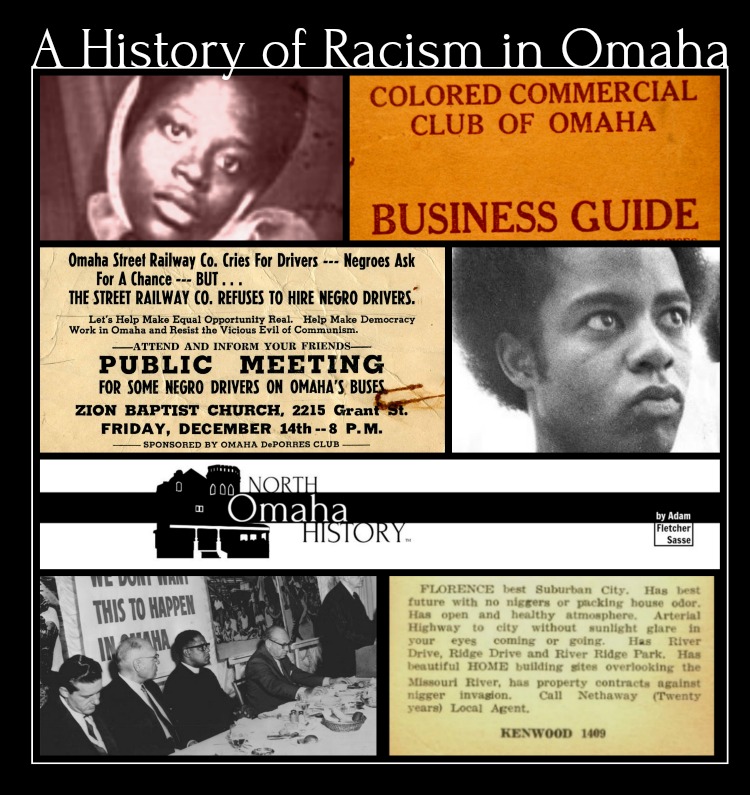

Summarizing Racism in Omaha History

Throughout this website, I have detailed the history of the Civil Rights movement in Omaha, as well as many of the ethnic and racial groups in North Omaha. I have also started articles about African Americans, Mexicans, Greeks, and several other ethnic and racial groups in Omaha on Wikipedia. I did this because of the patterns of cultural racism and structural racism in the city that are so startlingly obvious to anyone that actually pays attention.

Types of Racism in Omaha

I have found examples of more than 60 types of racism in Omaha history. They include economic racism, transportation racism, housing racism, social racism, and racism in government, including policing and education.

- Economic racism in Omaha includes jobs, salaries, benefits, and job security. In transactions for goods and services, racism affects access; quality of shopping experiences, and; treatment as customers. Being treated with respect includes trying cloths, returning clothes, being watched, being suspected of stealing, and more. Examples of economic racism exist in Omaha banking, insurance, and real estate in many ways.

. - Transportation racism in Omaha extends throughout the history of the city. From early streetcar rides and horse-drawn taxis, to bus rides and routes starting in the 1950s, and Greyhound rides and airplane flights afterwards, racism is apparent throughout. The streetcar company discriminated against African American and others in their employment practices, and later Omaha’s bus drivers, taxi companies and jitneys did, too. Even walking and bicycling in Omaha is often racist, as sidewalks and dedicated biking trails and on-street bike lanes are often poorly kept or unavailable in neighborhoods that are predominantly African American and other people of color.

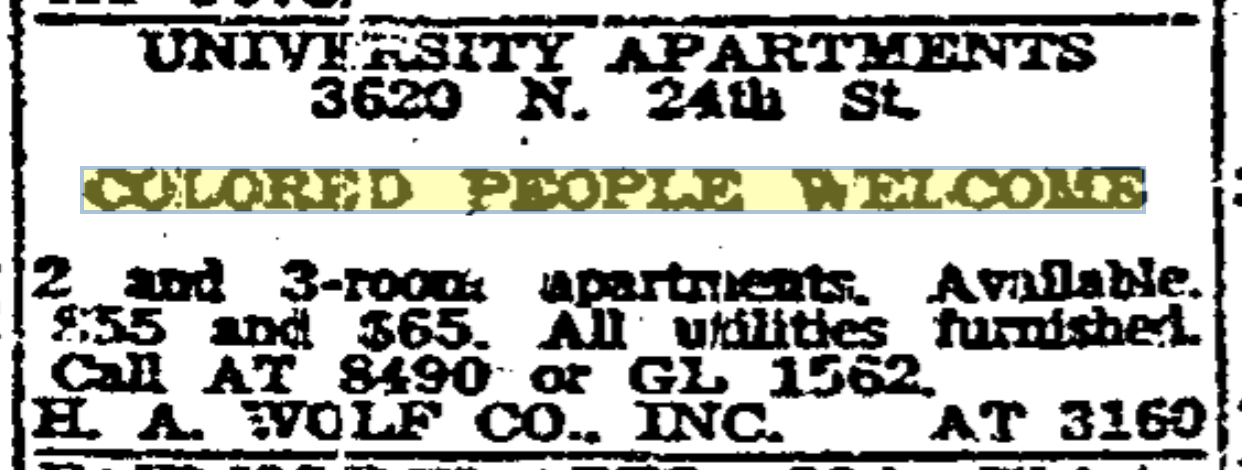

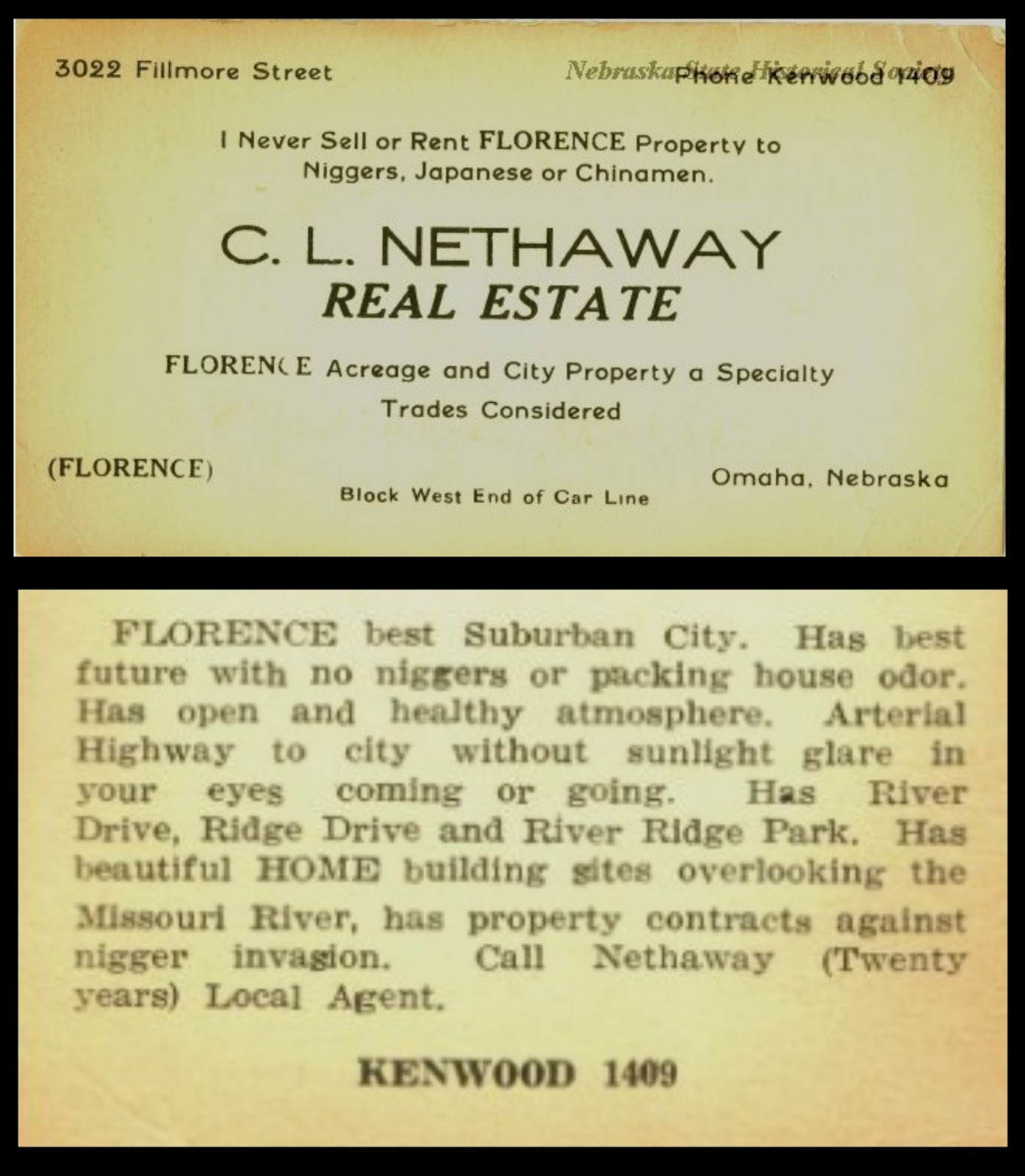

. - Housing racism in Omaha includes housing availability, home ownership rates, location, rents, home lending, landlord enforcement, insurance, rental upkeep, and housing trends. The recently-revealed and much maligned practice of redlining in Omaha enforces white supremacy, while less overt practices of social discrimination and economic segregation cover racist beliefs and actions, too.

. - Social racism in Omaha extends to all places and activities where people circulate, interact, and otherwise socialize. There are nearly countless examples of racism in Omaha’s social life, as the city’s churches are segregated, as well as sports, social clubs, bars and taverns, night clubs, hospitals, and different communities throughout the city are deeply segregated. The simple public appearance of Black people has been discriminated against throughout the city’s history, as have talking, recreation, music, eating out and fine dining, movies, performing arts theaters, social halls, concerts, and more. For young people today and historically, social places in Omaha have consistently been racist, including the Old Market; shopping malls; diners and cafes; pool halls and teen centers; summer camps; youth sports; swimming pools; and parks.

. - Government racism in Omaha is present throughout the city’s history. There are examples of racism from across the government of Omaha throughout the city’s history. Starting with the democratic process, including voting and political representation, it is obvious to see that political parties, political donations, government influence, and other functions of Omaha’s city government have been racist. The amount of racism throughout the Omaha Police Department throughout the history of Omaha is nearly indescribable. Summarized as “living while Black,” the practices and procedures of police in Omaha have repeatedly shown racism throughout history, including law enforcement, crisis response, neighborhood safety, and school safety; police brutality; and punishment. Unfair policing practices plague Black people and people of color throughout Omaha history. The legal system has shown rampant racism too, with imprisonment practices, legal representation, imprisonment and jails filling news reports and research on racism in Omaha. Other government services have been rife with racism, too, including public housing, parks and recreation services, public libraries, and the city’s infrastructure, including water quality, sewage, street maintenance, streetscapes, and much more.

. - Education racism in Omaha happens throughout formal and informal learning, teaching, and leadership. Public schools in Omaha are deeply entrenched in racism, too, including curriculum, teaching methods, classroom management, testing and assessment, and punishment and behavior management. The hiring of African American educators and educators of color, parent involvement, school investment, and many other education issues in Omaha have revealed racism continually since the city was founded. School siting, school district boundaries, busing, school naming, sports, extracurricular activities, school nutrition, and many other areas reveal the same, too. The school-to-prison pipeline in Omaha Public Schools and neighboring districts actively sends young African American boys and girls into a lifelong cycle of engagement with the legal system that ensures their enslavement to the system as well. None of this excludes the parochial and private school systems in Omaha, either: One of the two officially segregated schools in the city’s history was Catholic, and Black students have been discriminated against in many other ways by non-public schools also.

.

There are many other kinds of racism in Omaha history, too.

The patterns revealed in the following article show the reality that Omaha is racist. While this isn’t true of every single person in every single place all of the time, I believe it is important to highlight patterns of racism that define a part of the city’s historical character that few people readily acknowledge.

Early Racism in Omaha

Racism and segregation doesn’t just happen through big, bold actions that capture newspaper headlines. In reality, it is present in the everyday attitudes and actions of white people across the United States, myself included. This article highlights both big events and everyday realities.

In the history of the city, I quickly uncovered possible early patterns of ethnic discrimination by the founding Omaha Claim Club and other early civic leaders.

In 1859, the Omaha City Council heard a proposal to abolish slavery in the city, and quickly rejected it. In 1861, the Nebraska Legislature located in Omaha enacted a law prohibiting interracial messages. While the territory banned slavery in 1861, it took federal pressure to ensure voting rights for Black people in Nebraska after the Civil War.

In March 1867, newspapers recorded a mob of 400 white men in Omaha attacking 20 Black voters who tried voting. Black political activism against voter disenfranchisement happened in Omaha in 1868. In 1868, the Omaha school district opened a segregated school for Black students called the “colored school.” It was only closed in 1872 after two years of Black activists protesting the school board.

In 1889, a local African American singer named J.A. Smith died in the custody of the Omaha Police Department. He was arrested for “loud talking” on a public street. Just two years later Omaha experienced its first lynching when George Smith was lynched by a mob outside the Douglas County Courthouse. Almost 30 years later it happened again when Will Brown was lynched in 1919.

One of the first overt mentions of racially-based housing segregation in Omaha came from an 1895 article in the Omaha World-Herald. Discussing the location of a company of Black firefighters to fight fires in Black households, the newspaper declared that a neighborhood’s white residents took action to “draw the color line” and they wanted the Black company taken out of the neighborhood and replaced with white firefighters. That area, which is at South 27th and Jones Streets, was predominantly Black before then.

Everyday racism in Omaha kept early Blacks in the city confined to living in a small area near the Union Pacific Railroad Shops referred to as the “Negro district” in early newspapers. By 1900, that neighborhood moved north towards 21st and Paul Streets, and was referred to as Portertown because of the jobs many of the male residents had. As a professional class began emerging among African Americans in Omaha around the turn of the century, middle class Blacks weren’t allowed to buy houses outside the Near North Side.

African Americans fought racism throughout this era, calling out segregation and Jim Crow in many circumstances. For instance, in 1915 young attorney Harrison J. Pinkett called out new rules against Black people riding on the city’s public transportation system.

Segregated Realities

Everyday for more than 75 years, African Americans were excluded from the white economy of Omaha. Up and down 24th Street, whites owned stores that Blacks couldn’t shop at. Throughout downtown Omaha, African Americans weren’t allowed to shop, eat or otherwise spend money where whites did.

Housing was severely segregated from the outset of the city. With many euphemisms throughout it’s history, Omaha’s African American population has been routinely, systematically and deliberately excluded from white populations. Neighborhood names are often synonymous with Black residents, with the earliest African American neighborhoods being Porter’s Row, the Near North Side, Long School, Kellom Heights and 24th and Lake. Today, the entire North Omaha community is segregated from white Omaha by North 60th Street, while the city spreads to 180th Street and beyond. The city’s enormous public housing projects were largely associated with African Americans, too, before they were demolished. They included the Logan Fontenelle Projects aka Little Vietnam; Spencer Street Projects; and the Pleasantview and Hilltop Projects.

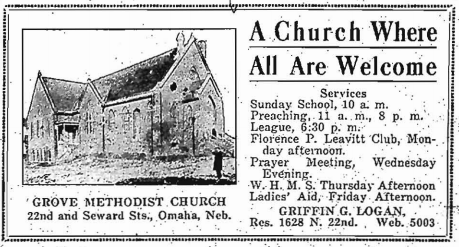

Institutions weren’t left out, either. Schools and churches in Omaha were highly segregated. The first Black church in Omaha was St. John’s AME Church, founded in 1865. Several others stand out for their longevity too, including: St. Phillip the Deacon Episcopal Church, now part the Episcopal Church of the Resurrection, founded in 1877; Zion Baptist Church, founded in 1884; Mount Pisgah Baptist Church, founded in 1886, later renamed Mount Moriah Baptist Church; Hillside Congregational Church, founded in 1886 and closed now; St. Benedict the Moor Catholic Parish, founded in 1918; Pilgrim Baptist Church, founded in 1918; Mount Nebo Baptist Church, founded in 1921; Bethel AME Church, founded in 1922; Salem Baptist Church, founded in 1922; Cleaves Temple CME Church, founded in 1924; and Hillside Presbyterian Church, founded in 1926 and closed now.

Originally de facto segregated, each of these churches represented an emerging tradition when they were founded. Today, Black churches have their own place among Omaha’s religious community and are revered for their longevity, vitality and unique perspectives and actions. However, Omaha shouldn’t forget that these churches are rooted in the racist belief that African Americans were inferior to white people, and that they weren’t worthy of worshipping in white churches.

!["The Election in Omaha," Hancock Jeffersonian [newspaper, Findlay, Ohio], March 22, 1867.](https://northomahahistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/white-mob-stops-black-voting-in-omaha-march-22-1867.jpeg?w=300)

In March 1867, a mob of 400 armed white people in Omaha ran off 20 Black men trying to vote in downtown elections. after the good guys won the Civil War seems something worth noting historically. Before that, they wrote a handbill and passed it out with this on it: “Notice to the N—–” of Omaha City.—The first Black Man that takes his stand at the Polls to vote he will get his head skinned to the Bone from his Enemy…”

Starting that same year, the city practiced Jim Crow education by opening the Omaha Colored School downtown. It operated until 1872, when Black parents’ protests to the Omaha City Council caused its closure. With neighborhood schools intact though, schools were segregated for more than a century. All originally serving kindergarten through eighth grades, Omaha’s Black schools included Howard Kennedy School, originally opened in 1885; Lake School, opened in 1879; Kellom School, originally opened in 1879; Lothrop School, opened in 1881; and Long School,

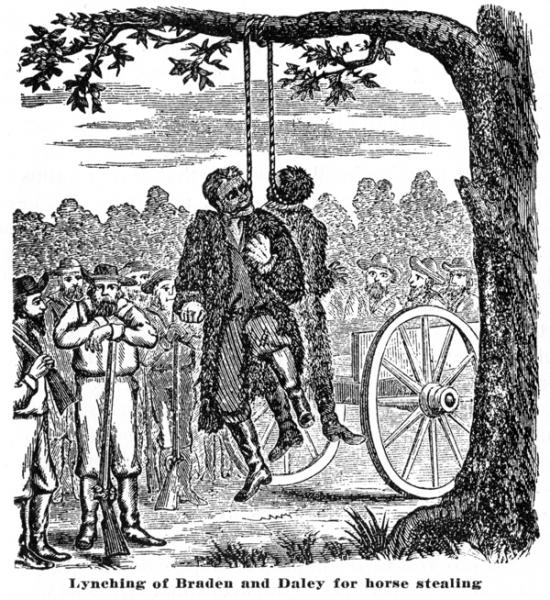

Lynchings in Omaha

The earliest gross injustice of racism arising in Omaha’s historical record is the story of a man alternately called Joe Coe or George Smith. Smith was a 50-year-old African-American railroad porter who was married with two children. He lived on North 12th Street north of downtown Omaha.

In fall 1891, Smith was lynched by a mob after he was accused of raping a white girl. Smith had an airtight alibi and witnesses that attested to his innocence. However, an all-white mob decided that because he had been convicted of rape several years before in neighboring Council Bluffs, Smith was guilty of raping this teen. After crowd of 10,000 gathered for the lynching, Smith was dragged from the jail, beaten, and dragged through the city. Seven men were arrested for the crime, including the chief of police and the manager of a large dry goods store, but none were convicted. During the subsequent trial, the county coroner attested to Smith dying from “fright” rather than anything physical.

There were a lot of ways that racism was shown throughout early Omaha, and a lot of ways that white privilege was used to enforce control and authority. In 1899, Rudyard Kipling reflected the view of many wealthy Omahans when he visited the city and wrote,

“The city to casual investigations seemed to be populated entirely by Germans, Poles, Slavs, Hungarians, Croats, Magyars, and all the scum of Eastern European States, but it must have been laid out by Americans.”

—Rudyard Kipling (1899)

Almost all of Omaha’s pioneer powerhouse names, including Creighton, Kountze, Brown, Poppleton, Hanscom and others were from established East Coast families who came to Council Bluffs to wait for the Nebraska Territory to open so they could make their names in the world. These Americans were born in the country, and often brought college educations and significant amounts of money with them to the city. In order to maintain and build their wealth, they routinely subjegated people from “unfavorable” European states to low paying, highly demand labor. Sewing the seeds of racism and disdain for anyone who didn’t please their views of what Omaha should be, they used hatred and distrust to build their empires.

This trend was continued by later power brokers, too, including Ed Rosewater, the publisher of the Omaha Bee, and his crony, Omaha’s boss Tom Dennison. The newspaper routinely used yellow journalism to promote bigotry, while Dennison played ethnic groups against each other like a fiddle.

Other lynchings and attempted lynchings happened in modern-day Omaha, too. In 1906, three African American men were arrested for the murder of an Omaha streetcar conductor during an attempted robbery.

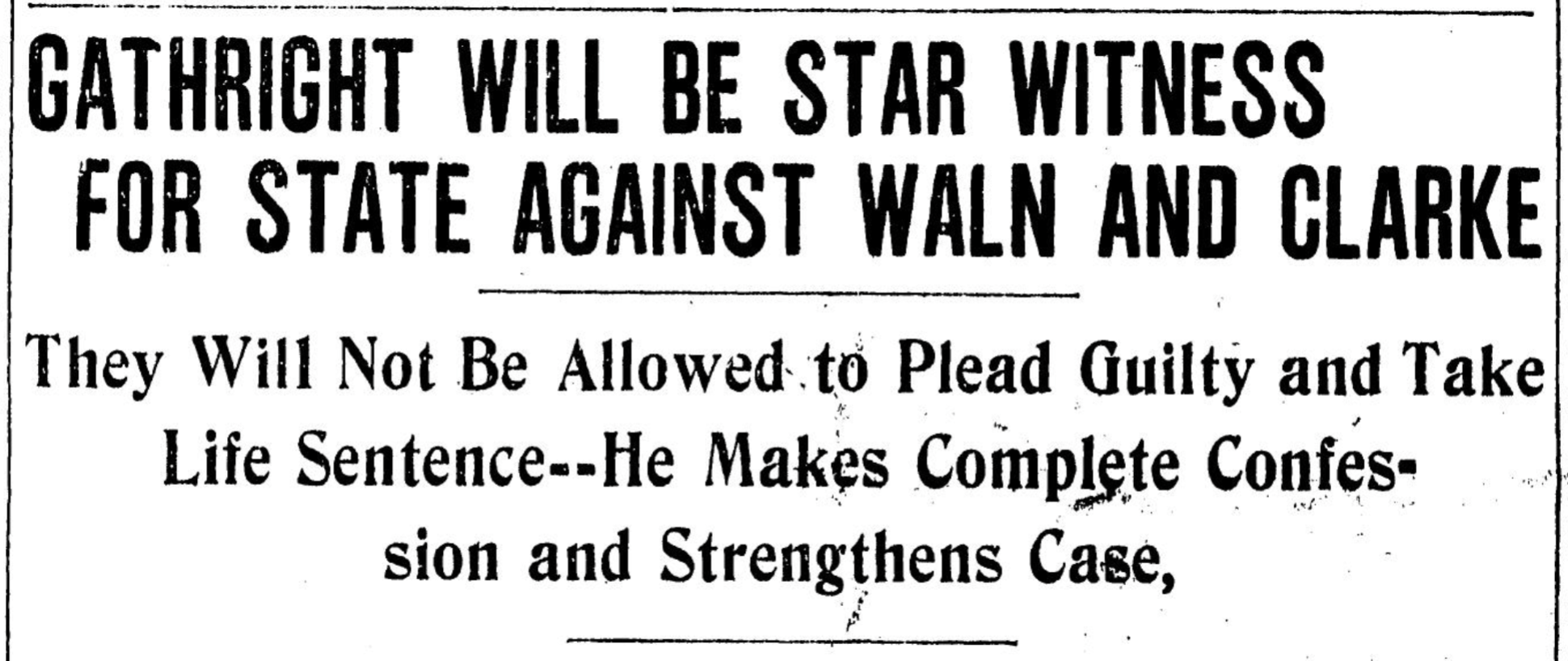

Harrison “Harry” Clark, Calvin Warren aka Cal Waln and Clarence “Pink” Gathright (1886-1946) were held in the South Omaha Police Department. After a mob gathered outside demanding to lynch the suspects, police moved the men to Lincoln to protect the prisoners. Soon the mob leaders were invited to inspect the station, and when they were not found the mob dispersed without further incident. Nobody was arrested related to the potential lynching. One newspaper said the trio were “anxious to get to the pen” [state penitentiary] to be protected from the mob, and because of that they admitted to the crime. Harry Clark confessed and was hanged for the murder, Cal Warren was sentenced to life in prison for his role, and because he testified against the others, Pink Gathright was sentenced to twenty years as an accomplice to murder. Harry Clark was hanged at the Nebraska State Penitentiary on December 13, 1907.

Soon after racists turned their vehemence toward destroying a neighborhood.

Omaha’s Greek Town Riot

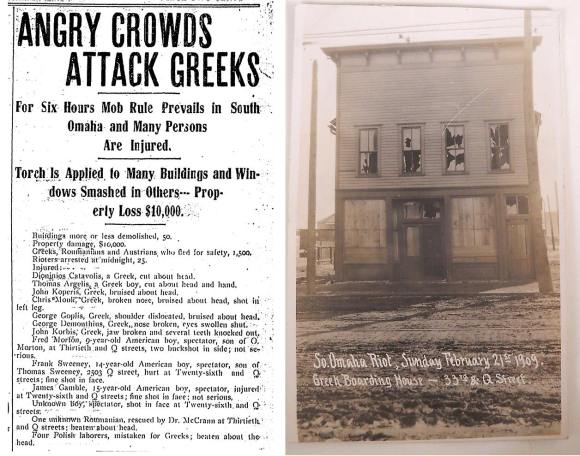

In 1909, Omaha’s Greek community was completely destroyed by racism.

At that time, Greeks were seen as non-whites, along with many southeast Europeans. When South Omaha was young, Greeks had come to the city to be laborers. Hired during tense strikes at the city’s stockyards in the 1890s, the city’s larger western European population became agitated towards the Greeks. Greeks were treated and popularly viewed as inferior, and this combined with a general appreciation for vigilantism led to a huge riot in February. On the 20th of that month, a Greek man named John Masourides was accused of murdering a police officer. When he fled the city, a mob gathered at the South Omaha jail turned on Greek Town near South 24th and Q Streets. Greek bakers, barbers, grocers and cafes that had been there for twenty and thirty years were told to leave the 4×4 block area, along with residents in tenements, boarding houses, and apartments. Within a few hours, the entire area was burnt to the ground. Again, nobody was convicted of any crime related to this event.

In 1910, a mob of hundreds of white men swarmed the city’s African American neighborhoods. World famous African American boxer Jack Johnson beat a white contender in a major title match in Reno, Nevada. After the upset, Omahans lost thousands of dollars in bets and decided to take it out on the city’s African Americans. They were met by a strong police presence, which dispersed the crowds before they could cause much damage.

Racism Thrives in Omaha

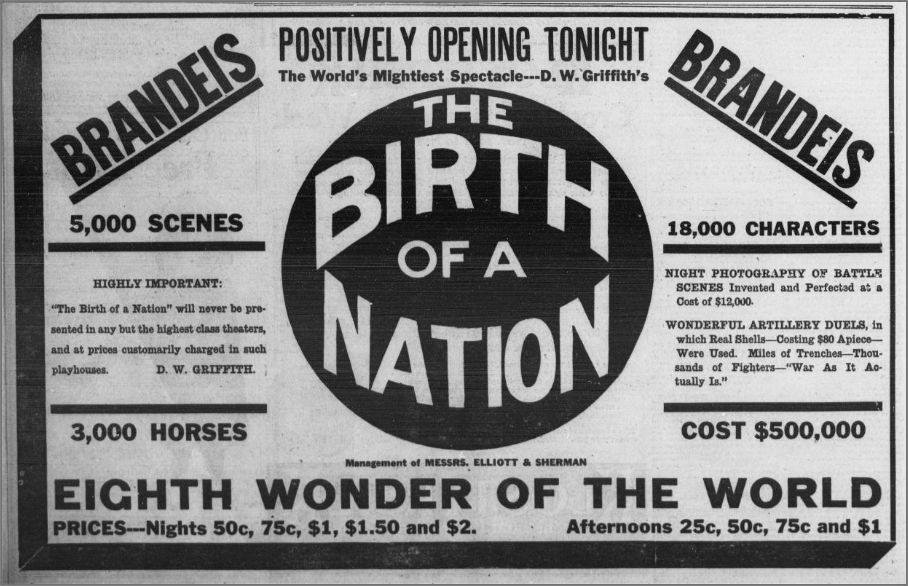

The Birth of a Nation is a vile, disgusting and despicable daydream of a hate-filled, vengeance-driven American director. It was very popular in Omaha.

Its release was challenged by Civil Rights activists with the NAACP, Urban League, and others. Many cities made grand showings over denying its showing – but not Omaha. Instead, in November 1918 it showed gladly and repeatedly at the Brandeis Theatre downtown. It proved to be so popular, in fact, that The Birth of a Nation was held over in Omaha for several weeks, continuously selling out of tickets for days in a row.

The Rev. John Albert Williams, editor of The Monitor newspaper, led much of the charge against the film. Using his paper, The Monitor asked if “Our Omaha Friends” would help prevent “Dixon’s Photo Play” from showing in the city and called for a meeting the next Sunday at Grove Methodist Church. “All fair-minded, justice loving people of the city” were called to “sustain us in this protest.” Williams quoted the author of the movie as saying,

“One purpose of the play is to create the feeling of abhorrence in white people, especially in white women against Colored men.”

—Rev. John Albert Williams quoting Thomas Dixon Jr (1864-1946), the avowed racist author of the original story behind The Birth of a Nation.

In 1931, more than 15 years after it came out, Mayor Richard Metcalfe wanted to make the movie illegal. He proposed a law to ban an film or play that, “tend[ed] to incite race riot or race hatred or which shall represent or purport to represent any hanging, lynching, burning or placing in a place of ignominy, any human being, the same being incited by race hatred.”

Apparently, the law passed.

The Second Recorded Racist Lynching in Omaha

In the years leading up to and during World War I, Omaha’s African American population doubled. White men had gone off to war as soldiers, and when Black men were limited to support roles in the war only, many stayed home. Moving to Omaha for jobs in the meatpacking and smelting industries, they weren’t accepted by Omaha’s hostile white majority.

Starting in 1917, a homegrown hate group called the Committee of 500 began rallying white Protestants in a pro-Prohibition, pro-Reformist political slate openly intended to promote white supremacy. Although it took four years for their racist agenda to be exposed by the Black media, several horrific things happened in the city that peaked in 1919. Early that year, police brutality against Black people was shown to be on the uptick. On September 1, 1919, an African American veteran was shot and killed by Omaha police for running away from the scene of a suspected crime. However, that only set the stage for what was to come.

Almost 30 years after its first notorious lynching, Will Brown suffered a similar fate to George Smith during the Red Summer of 1919. That term is used by academics to describe a summer when racists across the United States lynched blacks and destroyed communities across the country. This disgusting act of white supremacist terrorism echoed loudly in Omaha, blaring out with Brown’s case. After labor-related clashes between white and black workers at the Omaha Stockyards earlier in the summer, racial tension crackled through the air. They peaked in late September when Brown, an African-American worker, was accused of raping a 19-year-old white woman. Three days later, a crowd of people marched from Bancroft School in south Omaha to the city jail downtown, swelling to 5,000 by 5:00pm. By nighttime more than 10,000 people were gathered, and when they stormed the courthouse were Brown was held, resistance was futile. The city’s mayor was rescued from being hung after the crowd mobbed the courthouse, but Brown had the opposite fate. After being beaten and dismembered, the remains of his corpse was burnt. Nobody was ever convicted in the trial afterwards.

The first Klu Klux Klan group in Omaha was formed in 1921. According to the Omaha World-Herald, in 1917, a regiment of Black soldiers was stationed at Fort Omaha. White people in the surrounding Miller Park neighborhood protested a lot, writing letters to the newspaper and their elected officials. African American community leaders and politicians took it upon themselves to sound out loudly on behalf of the troops. Influential local civil rights leader John Singleton worked with Gene Thomas, a past commander of the Legion Post of Spanish War Veterans, and others to promote the inclusion of the troops there. The neighborhood eventually shut up.

During these early years, the Civil Rights movement was gearing up in Omaha with local and national action in the city. The National Federation of Colored Women, National Colored Press Association and other national organizations promoting Civil Rights had footholds, leadership and meetings in Omaha. Soon after, other national organizations became active in North Omaha, including Marcus Garvey’s United Negro Improvement Association, or UNIA; the African Blood Brotherhood, or ABB; the Urban League, and; the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, or NAACP. Each of these formed strong organizations within Omaha that left big impacts.

The Civil Rights Era

From the 1900s all the way through the early 1970s, there was a vibrant Civil Rights movement in Omaha. Rallying together to struggle against discrimination, African Americans led a movement for equal employment, equal pay, equal housing, equal purchasing, equal access, and equal justice with white people throughout the city.

As they pressed on, a variety of organizations and individuals came together to advocate for Civil Rights for African Americans, becoming increasingly organized and effective in their actions.

In the midst of these efforts, the United States was bombed by Japan at Pearl Harbor in 1941. True to form, Omaha immediately imprisoned all people in the state who remotely looked Japanese. This included Rev. Hiram H. Kano, a minister from Scottsbluff who was in town for business. Despite being an Episcopalian minister, he was immediately apprehended and jailed in Omaha.

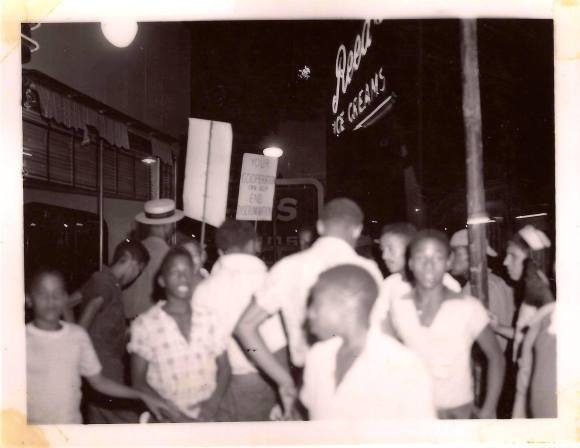

Omaha was deeply segregated at this point. While the laws were mostly silent, de facto segregation was the norm across the city. Police weren’t needed to kick African Americans out of places like Peony Park because Blacks knew they weren’t welcomed there, and were threatened with intimidation and violence if they tried going. Restaurants like Joe Tess and Mister C’s served Blacks at their back doors and refused them entry, while Reeds Ice Cream would gladly let African Americans order ice cream, but wouldn’t let them apply for jobs. The same went for the local Coca-Cola bottlers and for the streetcar company, which gladly took Blacks’ money but wouldn’t hire them.

The Jewish community was the target of discrimination, too. Originally congregated in the Near North Side neighborhood, when Jews tried to move to different parts of the city they routinely found race restrictive covenants in the neighborhoods where they tried to move to. As a response, an entirely Jewish neighborhood was built northwest of Memorial Park after World War II. Called “Bagel“, it became a center of Jewish Omaha’s identity for decades. Earlier, in 1924, Omaha’s Jewish community opened the Highland Country Club at South 132nd and Pacific Streets because the Omaha Country Club and others banned Jewish members. In the 1960s, Warren Buffett intentionally joined the Highland Country Club in order to make a statement about Omaha Country Club’s discrimination.

Before 1963, African Americans weren’t allowed to go to Peony Park or swim in their pool. That year, the Omaha NAACP Youth Council began a protest of the park’s segregation rules that kept them from swimming there. After closing because they broke Nebraska segregation law in 1955, Peony Park “reopened as a private club—a popular Southern strategy for avoiding court-ordered integration of public places.” After protests in 1963 led by the NAACP, white people stopped going in great numbers through the summer, and Peony Park lost money. The park dropped their policy and African Americans were allowed to use the park for the first time that year.

In his autobiography, Preston Love, Sr. reported that in restaurants across Omaha, there was one sign that was repeated:

“We Don’t Serve Any Colored Race”

—Preston Love Sr. reporting these signs were in Omaha restaurant windows

Hotels and shops in Omaha were segregated, too. There were several Black hotels that existed from the 1890s through the 1960s, including the Booker T. Washington Hotel; Calhoun Hotel; Broadview Hotel; and several others. Most stores in downtown Omaha were off-limits to African Americans, either through intimidation or simple denial. One of the first targets of anti-racism protesters during the Civil Rights movement was the cafeteria in the basement of the Douglas County Courthouse, as well as the Woolworth’s in downtown Omaha.

By the turn of the 20th century Omaha’s schools became incredibly segregated, with the entire African American student population in the city sent to just a few schools. A couple schools were completely Black, and a few others were known for being Black schools. Segregated schools in Omaha included Lake, Lothrop, Kennedy, Kellom and Howard Kennedy. In Omaha, segregated schools didn’t mean a building was exclusively for Blacks; it meant that Black people weren’t allowed to go to schools other than ones white people wanted them to attend.

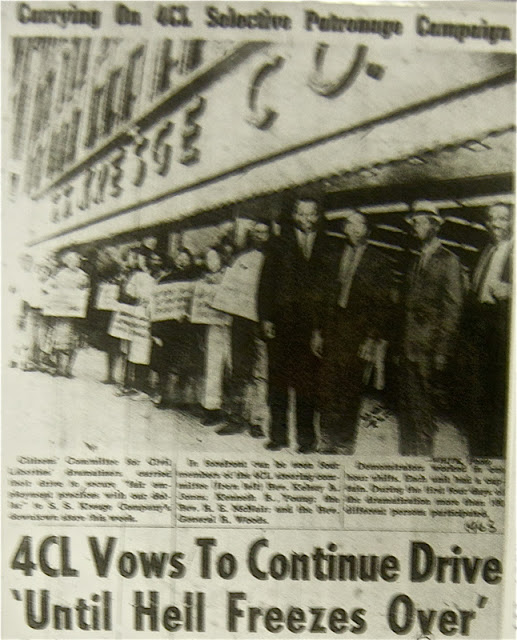

By the middle of the century, students at Creighton University were working together with the Near North Side’s African American community through the DePorres Club, with their work followed by a local campaign called the 4CL – Citizens Civil Liberties Committee. They picketed and boycotted, protested and proposed legislation to challenge Omaha’s cultural and systematic racism.

As the movement took hold, the DePorres Club aligned with CORE, or the Congress of Racial Equity; Dr. King spoke in Omaha at a national Baptist conference and at Salem Baptist; and other national movements took hold in the city.

Throughout the years, some of the groups and organizations involved in Omaha’s Civil Rights movement included the Negro Republican Club, Young Men’s Colored Independent Political Club, Lincoln Motion Picture Company, Alpha Eta Chapter of Kappa Alpha Psi, Hamitic League of the World, African Blood Brotherhood (ABB), the Omaha branch of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), the Omaha Urban League, Omaha NAACP, NAACP Youth Council, Near Northside YMCA, the Negro YWCA, National Federation of Colored Women, Colored Commercial Club, Industrial Workers of the World, Knights of Liberty/Knights of Tabor, Omaha Congress of Representatives of White and Colored Americans of 1898, Colored Old Folks Home, Negro Ministerial Alliance, Omaha branch of the National Colored Press Association, Citizens Civic Committee for Civil Liberties (4CL), DePorres Club, City of Omaha Bi-racial Committee, Omaha Black Panthers, Black African Nationalism through Unity (BANTU), Malcolm X Memorial Foundation, Omaha Public Schools, MAD DADS INC., Great Plains Black History Museum, Black Liberators for Action on Campus (BLAC), 1894 Afro-American Fair Association, City of Omaha Human Rights Commission, Concerned & Caring Educators Foundation, Omaha Union League Club, and the National Afro-American League (NAAL). Today, Black Lives Matters, NOISE (North Omaha Information Serves Everyone), and several other organizations continue carrying the mantle.

Over more than 100 years, thousands of people have been involved in Omaha’s Civil Rights movement. They included Rev. John Albert Williams, George Wells Parker, Earl Little, Malcolm X, Harry Haywood, Whitney M. Young, Jr., Thomas H. Warren, Sr., Mildred Brown, Captain Alfonza W. Davis, Sally Bayne, Edwin Overall, Henry Clay Curry, Ida Overall, Comfort Baker, Silas Robbins, Dr. Matthew O. Ricketts, Ferdinand L. Barnett, Claus Hubbard, Dr. W.H.C. Stephenson, Lucy Gamble, Clarence Wigington, James C. Greer, Sr., Lucille Skaggs Edwards, Harrison J. Pinkett, John Grant Pegg, Rev. William Tate Osborne, George and Noble Johnson, Joseph S. Ballew, Alphonso Wilson, Dr. Aaron M. McMillan, Lloyd Hunter, Thomas Mahammitt, John Owen, Pitmon Foxall, William A. Woods, Richard D. Curry, Charles Davis, Eugene Skinner, Elizabeth Davis Pittman, Harold L. Biddiex, Marge Rose, Herbie Davis, Gale Sayers, Monroe Coleman, Edmae Swain, Ambrose Jackson Jr., Marlin Briscoe, Darryl C. Eure, Ella Mahammitt, Rudy Smith, Rodney S. Wead, Joe Coe aka George Smith, Will Brown, Ernie Chambers, Don Benning, Gene Haynes, Claude J. Organ, Lillian D. Anthony, Katherine Fletcher, Cathy Hughes, Edwina Justus, Preston Love Sr., Preston Love Jr., Bertha Calloway, Brenda Smith, Cyrus D. Bell, Fred Conley, Brenda Council, George F. Franklin, Rev. Annie Woodbey, Linda Brown, Carol Woods Harris, Nathaniel Hunter, Cleveland Vaughn, Jr., Bertha Calloway, Denny Holland, Jessie Hale-Moss, Steve Hogan, Wanda Ewing, Helen Mahammitt, Marlon Polk, Lucinda Williams, Tanya Cook, Vivian Strong, Alfred Barnett, Ed Poindexter, Dorothy Stubblefield, Mondo we Langa (David Rice), Father John McCaslin, Frank Peak, Dr. John Andrew Singleton, John Adams, Jr., John Adams, Sr., Edward Danner, George W Althouse, Rev. James T. Stewart, Rev. John Albert Williams, Father John DeMarkoe, Rev. Rudolph McNair, Rev. Russel Taylor, Eugene Scott, J. A. Smith, G.S. Kennedy, George E. Collins, John Wright, J. W. Long, Rev. R.F. Jenkins, Dr. Marguerita Washington, James Bryant, Millard Singleton and Dan Desdunes, as well as Eddie and Lizzie Robinson and many, many other people.

Some of the churches involved in the Civil Rights movement in Omaha include St. Phillip the Deacon Episcopal Church, St. John’s African Methodist Episcopal Church, Salem Baptist Church, Mt. Moriah Baptist Church, Hope Lutheran Church, Calvin Memorial Presbyterian Church, African Baptist Church, Zion Baptist Church, Clair Memorial United Methodist Church, Bethel AME Church, Cleaves Temple CME Church, Pilgrim Baptist Church, Hillside Presbyterian Church, Augustana Lutheran Church and others.

They won major battles, including integrating several businesses, passing key housing, employment and labor legislation, and other initiatives focused on defeating discrimination. However, they failed too, finding the city’s racism too entrenched to overcome more than once.

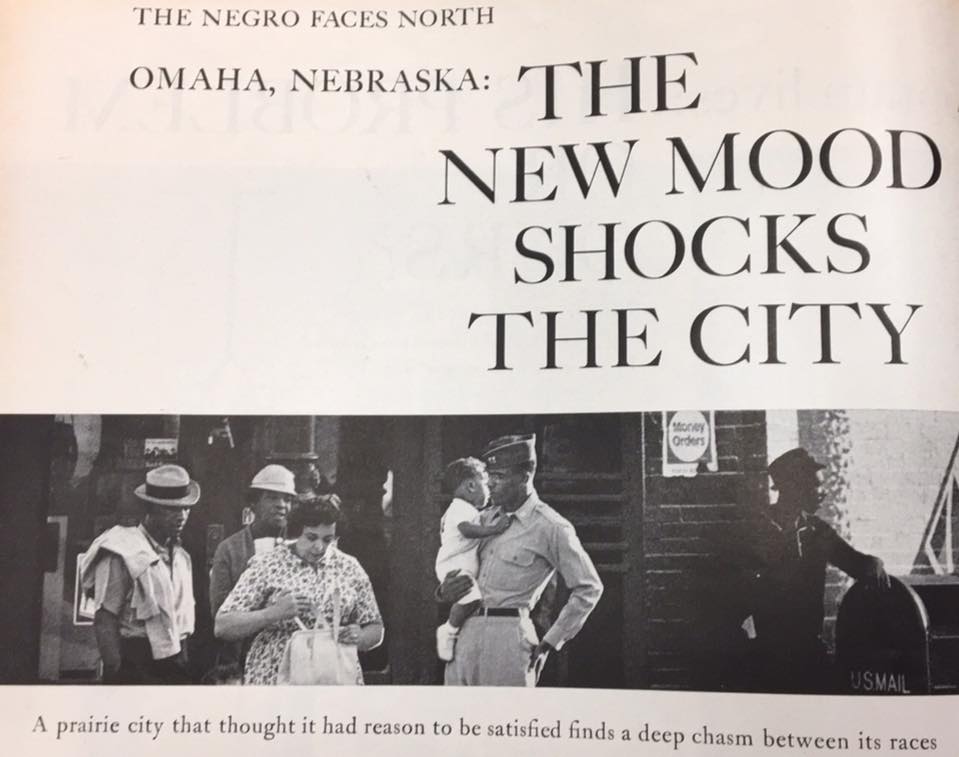

Racism in Omaha Today

These events, along with many others, establish an early pattern of discrimination in the culture and government of early Omaha. While protests against Japanese immigrants; anti-Black riots after boxing matches; the systematic segregation of African-American teachers into exclusively African-American schools; and anti-Polish hatred leading to the burning of a Catholic Church may seem like distant, distinct, and disconnected phenomenon in the city’s history, news today show that activities like police discrimination, redlining, and school segregation are rampant throughout the city today.

The city’s rapidly growing Hispanic and Latino population – which grew by 155% from 1990 to 2000 – is making it as obvious as ever that Omaha is racist. Isolated, segregated and discriminated against throughout Omaha, this population is now grouped almost entirely in South Omaha, with little outreach done by white Omaha to integrate them throughout the city.

Modern Resegregation in Omaha Public Schools

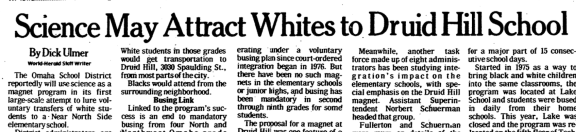

Omaha Public Schools are re-segregating today. According to OPS data, percentage of white students enrolled in Omaha Public Schools is decreasing while the percentage of students of color is rising, especially in schools with predominantly African American and Hispanic / Latino student populations. This is happening while the general Omaha population has increasing numbers of white people and a decreasing population of African Americans.

A variety of schools in North Omaha have large percentages of African American students that demonstrate racial unevenness in school. For instance, at North High, Blackburn High, and Northwest High, African American students comprise the largest racial populations in the school. Other schools show racial isolation, including Burke High, Alice Buffet Middle, and Davis Middle. The UNO Middle College Program and the Gateway to College Program are also predominately white, while Hale, King, Monroe, Morton, and McMillan are predominately African American. Transitions Program, Career Center and Parrish are also predominantly African American.

In the 2015-16 school year, the trends of racial isolation in Omaha Public Schools are even more pronounced in elementary schools. Belvedere, Central Park, Conestoga, Druid Hill, King, Franklin, Lothrop, Miller Park, Mountain View, Saratoga, Skinner and Wakonda are all majority African American schools. Unevenness in Omaha Public Schools is apparent in Caitlan, Columbian, Dundee, Florence, Fullerton, Picotte, Pinewood, Saddlebrook, Standing Bear, and Washington elementary schools all have majority white student populations.

This is all evidence of the ineffective administration of resources among Omaha Public Schools, and demonstrates how North Omaha is routinely afflicted by racial segregation. I have not shared an analysis of per school spending, neighborhood economic status or other factors that will corroborate these findings; however, that information is forthcoming.

Omaha’s Current Color Code

In the last 25 years, Omaha’s white population has created a gigantic, undeniable color line between west Omaha and the rest of the city. In the western portion, almost no people of color have homes, let alone shop, eat, watch movies or otherwise engage with white people.

That anti-Black sentiment isn’t limited to west Omaha though, because its still wildly active in East Omaha, too. In 1981, an African American family signed a lease for a duplex in East Omaha. It was burnt down within a week. In 2007, an Ethiopian immigrant bought a grocery store in East Omaha. Within a month, the building is robbed, vandalized and spray painted with racist hate messages, and ultimately fire bombed and destroyed.

Black Lives Matter in Omaha, Too

Violence targeting African Americans continues in Omaha.

The famous and notorious work of the Black Panthers starting in the late 1960s shined a light on the Omaha Police Departments illegal tactics demonstrating bias against African Americans and low-income people in North Omaha. In just five years of their existence, the group protested, rallied and challenged white supremacy in Omaha, leading to the arrest of two leaders, David Rice and Ed Poindexter, for the murder of policeman Larry Minard. Despite the absence of evidence and persistent demonstrations of their innocence, the men have been in jail since 1972. Rice died in prison in 2016, and Poindexter is reportedly in ill-health.

In 1997, an African American Persian Gulf War veteran was shot dead by officers from the Omaha Police Department in a controversial shooting. In 2000, an African American named George Bibbins was shot and killed by police after a high speed chase by Omaha police. In 2014, four police officers were fired and three suspended for the beating of 28-year-old Octavius Johnson. They grabbed him from behind, violently threw him to the ground and punched him while he was restrained. More than 20 officers and a commander showed up on the scene. Several other officers are seen chased Johnson’s brother, Juaquez Johnson into a nearby home. This disciplinary action wouldn’t have happened had the entire event not been filmed by a neighbor. The family sued the police department, and it was revealed that the entire event was essentially over a parking ticket.

Rather than being one-off incidents though, these actions are part of a pattern of ongoing racism in Omaha. You can learn more about Omaha’s current treatment of African Americans in my article called “Fast Facts about African Americans in Omaha.” And remember – its about more than African Americans, too, since people of color are targeted throughout Omaha, including anyone who dresses or talks differently, and basically, anyone who is not white.

What’s next? Only time will tell.

You Might Like…

MY ARTICLES ABOUT CIVIL RIGHTS IN OMAHA

General: History of Racism | Timeline of Racism

Events: Juneteenth | Malcolm X Day | Congress of White and Colored Americans | George Smith Lynching | Will Brown Lynching | North Omaha Riots | Vivian Strong Murder | Jack Johnson Riot

Issues: African American Firsts in Omaha | Police Brutality | North Omaha African American Legislators | North Omaha Community Leaders | Segregated Schools | Segregated Hospitals | Segregated Hotels | Segregated Sports | Segregated Businesses | Segregated Churches | Redlining | African American Police | African American Firefighters | Lead Poisoning

People: Rev. Dr. John Albert Williams | Edwin Overall | Harrison J. Pinkett | Vic Walker | Joseph Carr | Rev. Russel Taylor | Dr. Craig Morris | Mildred Brown | Dr. John Singleton | Ernie Chambers | Malcolm X

Organizations: Omaha Colored Commercial Club | Omaha NAACP | Omaha Urban League | 4CL (Citizens Coordinating Committee for Civil Rights) | DePorres Club | Omaha Black Panthers | City Interracial Committee | Providence Hospital | American Legion | Elks Club | Prince Hall Masons | BANTU

Related: Black History | African American Firsts | A Time for Burning | Omaha KKK | Committee of 5,000

- Black History in Omaha

- Notable African American Women in Omaha History

- History of African American Politics in North Omaha

- A History of Antisemitism in Omaha

- A History of Relations between Jews and African Americans in Omaha

Related Features

- “Unraveling Racism with Adam Fletcher Sasse” Annette van de Kamp, Jewish Press. (November 16, 2021)

- “North Omaha History’s Adam Fletcher Sasse on Racism’s Legacy in Metro,” Tom Knoblauch, KIOS (October 9, 2021)

- “#OmahaBlackHistory book embraces community’s past” Melissa Fry KETV (March 11, 2021)

- “Adam Fletcher Sasse Joins the Show” Pat & JT podcast (December 9, 2020)

- “Leaders In Purpose ep 19 Adam Fletcher Sasse” C.C. Alexander KPAO (November 14, 2020)

- “Current protests across the country evoke memories of 1960s Omaha” Paul Guitterez KPTM (May 29, 2020)

- “Adam Fletcher Sasse – Learning from North Omaha’s History” Inside Omaha podcast (July 5, 2019)

BONUS PICS

Leave a comment